It’s been nearly three decades since she was floating on a ship in the North Atlantic, as anxious as a kid on Christmas morning to see what would be raised from the depths, but Rhonda Wozniak still talks as if she’s in the middle of it all. A Pittsburgh-based expert in marine objects conservation, she channels the nervous energy she felt back in 1994 as artifacts from the Titanic transitioned into her care after more than 80 years at rest, including the odd feeling of having a 56-man crew peering over her shoulder as she scrambled to protect all those remnants from the sunlight and oxygen on a makeshift lab in a shipping container, rocking back and forth with the ocean’s waves.

“When you get to the wreck site and realize you’re the first person to touch these artifacts after the passengers perished and suffered such a horrifying death, it gives you chills,” Wozniak says.

Wozniak served as the conservator on the four-week 1994 expedition that marked the third RMS Titanic Inc. visit to the wreck site. She then worked for two years at LP3 Conservation in France, preserving the Titanic’s artifacts. Afterward, she returned to Pittsburgh, her hometown, to conserve the Chariot of Aurora mural from the French ship, the Normandie, at Carnegie Museum of Art, where she worked for a decade, primarily as the objects conservator. Many of the objects she treated appear in TITANIC: The Artifact Exhibition.

During the Titanic expedition, Wozniak never ventured to the sea floor. She was too busy working through the night to treat and stabilize the diverse collection of objects recovered—everything from crystal decanters and third-class coffee mugs to the ship’s fittings, such as bronze portholes and cast iron bollards—all of them changed by decades spent in conditions from which nothing had ever before emerged.

When smaller objects arrived in the basket of the Nautile submersible, Wozniak quickly placed them into tubs to be covered with water once again, then carefully cleaned each one with a soft brush so they could be inventoried, measured, photographed, and their condition assessed. It was a revelatory experience for a conservator—and for the broader world of conservation—with a host of challenges unique to this wreck.

“I had the unfortunate experience of running out of gloves while cleaning the artifacts,” Wozniak says. “My hands were literally burning from the acidic silt.”

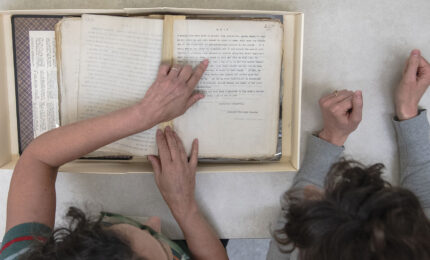

Wozniak describes the “miraculous” treatment of papers recovered inside of suitcases. Stacks of paper were freeze-dried so pages could be separated and bathed in a chemical solution to reduce and remove sulfides that had blackened them in their time underwater. Before her eyes, she saw one stack revealed to be letters—love letters. Along with a colleague at LP3, she read the letters, wondering if their author had ever returned to his paramour. “It brought tears to my eyes,” Wozniak recounts.

Given the fact that more than 1,500 passengers and crew members died when the ship sank, so many of the artifacts recovered from the wreck carry a similar emotional weight. A gold pocketwatch was returned in 1993 to Edith Haisman, who had survived in a lifeboat at age 16. It had been her father’s; the last time she had seen it was 81 years earlier when he was waving to her from the deck of the sinking ship.

As a conservator, Wozniak says she hopes her work can preserve for future generations the love letters and pocket watches that offer people a connection to such a specific time and place.

Each object brings its own challenges. After the cork popped on a full bottle of champagne once it was recovered, Wozniak knew she needed six people standing by to secure the corks on the half-dozen other bottles. One of those bottles is part of the exhibition at Carnegie Science Center.

At LP3, organic materials like paper, wood, textiles, and leather were prioritized to reduce corrosion that would make them brittle. Hydrolyzed components of these artifacts had to be replaced so their structures had the necessary support to be removed from water baths in order to mitigate biological damage. Metal objects, meanwhile, needed to be placed in an alkali solution to be desalinated without further risk of corrosion. Depending on the metal, an artifact’s surface was treated, dried, and coated to protect against future corrosion.

No matter the artifact, the guiding principle was to stabilize it and preserve as much of the history of the shipwreck as possible, so the world could see an honest representation of what remained.

“If you do your job well, people don’t know that you did it at all. It shouldn’t show,” Wozniak says. “Conservation may be somewhat of a thankless profession, but in the end our thanks is that the objects are still surviving and they’re still stable and they’re still here for future generations.”