Whether arriving by horse-drawn carriage as they did at the end of the 19th century or by electric vehicle as they will in the 21st, concertgoers in Oakland’s Carnegie Music Hall might share the same feeling upon entering the cavernous half-circle auditorium filled with row upon row of cabernet-colored velvet seats:

Wow.

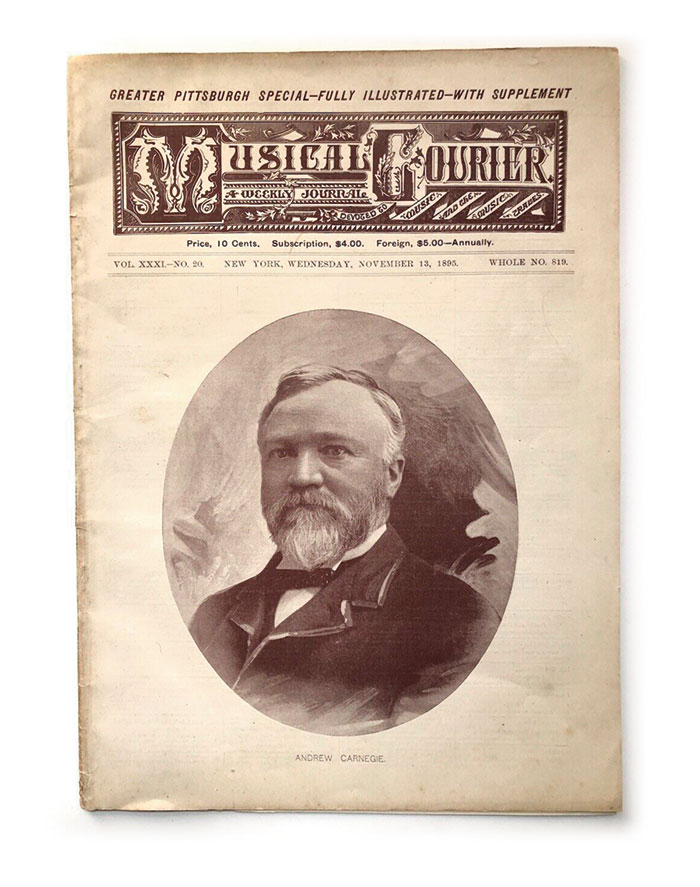

When the hall opened with its first concert on Nov. 5, 1895, it was a national story—one that inspired a Pittsburgh-themed special issue of the New York City-based Musical Courier. The prominent weekly extolled the hall’s three-tiered, 2,000-seat, domed-ceiling hall, including the “elaborate and handsomely decorated proscenium arch [that] springs from the stage … [the decoration] everywhere accented with gold, heightened by the use of the electric light … the effect appropriate to a palace of music.”

The hall was part of a gift from Andrew Carnegie to the growing city of Pittsburgh—a cultural complex that included a library as well as museum wings dedicated to art and science. It aimed to fill a need for what a Courier writer called “important concert giving” to improve the lives of the rich as well as the poor, while supporting itself and the rest of this new Carnegie Institute.

Carnegie Museums once again aims to serve the public and generate revenue with the modernized version of the music hall, which closed in June 2023 for its most substantial renovation since it opened 128 years ago.

“Carnegie Music Hall is a cultural treasure of deep historical significance, not just to Carnegie Museums but all of Pittsburgh,” says Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh President and Chief Executive Officer Steven Knapp. “Just as it was a gift to the community well over a century ago, the renovated Music Hall will be a gift to the larger community of organizations that will welcome guests into this beautifully restored space.”

The $9 million project has painstakingly preserved the hall’s beauty and bones, including the sconces along the back wall of the first balcony and flowers on the arch. Those plaster pieces that were broken or missing were restored using molds of the originals sculpted by Carnegie Museum of Natural History paleontology preparators accustomed to working with millions-year-old fossils.

Carnegie Museum of Art conservators guided painters in matching antique and modern paints and using cotton swabs and vinegar to clean decorative panels. Scores of workers re-plastered, repainted, and cleaned gold leaf all the way up to the ceiling fleurs-de-lis.

But the renovation wasn’t just about aesthetics, says Melissa Simonetti, a seasoned design professional with a preservation background. Carnegie Museums hired her as the director of construction and project management, starting with this marquee project.

“Carnegie Music Hall is a cultural treasure of deep historical significance, not just to Carnegie Museums but all of Pittsburgh.”

–Steven Knapp, Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh President and Chief Executive Officer

The bulk of the renovation added critical updates such as new wiring and climate control—including, for the first time, modern air-conditioning—as well as improved accessibility. Custom-designed wider seats and aisles with slopes replacing steps will meet current building codes and maximize comfort and safety.

“What makes this renovation important is, we’re making it more usable to more people,” Simonetti says. The challenge, she notes, especially for an institution dedicated to preserving old things, is “to reach the right balance of making something code-compliant and new again while also keeping its character.”

Honoring a Historic Space

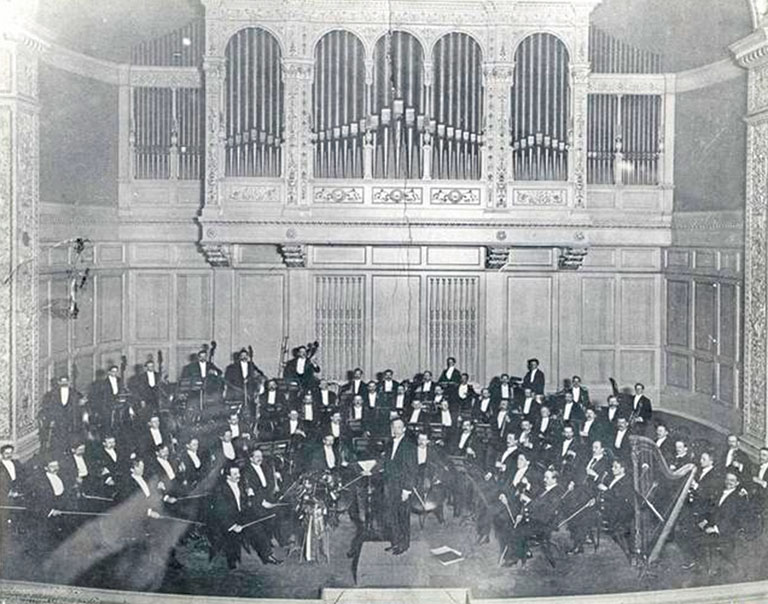

The vintage grandeur of the hall has hosted an historic array of diverse performers, including the Pittsburgh Orchestra, which started at the music hall in 1896 and became the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra. Other performers range from Italian opera tenor Luciano Pavarotti to popular singer Norah Jones, and speakers including five U.S. presidents.

Events in the hall have paid tribute to Fred Rogers, the victims of the Tree of Life synagogue shooting, and University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine students getting their white coats.

And the hall will once again be the home venue of local groups such as Pittsburgh Arts & Lectures, which in early January announced the spring return to the hall of its Ten Evenings series “with great joy.”

Rachmaninoff performed here. So did “Weird Al” Yankovich.

And on a late afternoon in mid-December, Michael Volpatt stood on the stage of the darkened hall, after crews had left for the day, and delivered a moving soliloquy about what it means to his family’s Volpatt Construction to partner on overseeing the project.

“When I walked into this space, I was overwhelmed by the greatness of it,” he says in a hushed tone that nevertheless carried into the rafters of the empty hall. His company is known for its renovations of historic edifices, such as nearby St. Paul Cathedral on Fifth Avenue, a French Gothic church on the National Register of Historic Places that was built several years after Carnegie Music Hall. However, Volpatt adds that his firm has “never done a music hall of this magnitude.”

At the height of construction, the music hall was filled with a thick 60-foot-tall forest of steel scaffolding. Volpatt climbed up in the dome to explore the attic, where he marveled at an old film projector still in a tiny, tucked-away office. It was just one of the hidden treasures of the hall, which includes its epic pipe organ—still not in full working order because it wasn’t part of this restoration, save for some cleaning of its exposed pipes behind the stage.

Volpatt looked down to show off a new feature that today’s patrons will never see: the entirely new floor in the orchestra and circle level, its gentle curves and slopes sculpted in many differently shaped custom cuts of plywood.

“They built a puzzle without pieces, is how I like to put it,” he said of the floor. “I love to point it out and I love to walk it. It magnifies the skill set of the carpenters on this project.”

All told, Simonetti says, people from more than a dozen companies contributed—“a lot of experts.”

Their work required a lot of materials, too, including 60 tons of scaffolding, 400 sheets of plywood, and 3,000 square yards of carpet. Carpenters, painters, and art conservators sanded and refinished 40 doors, restored 43 sconces, reapplied 1,179 fleur de lis stencils, and cleaned 33 decorative art panels on the orchestra level and 11 original decorative gold leaf panels on the proscenium arch.

Simonetti notes, “We rewired every single light,” with LED bulbs chosen for casting the same warmth. Her favorite transformation is to see the soot-scrubbed arched ceiling gleaming so brightly.

By January, the floors were covered with a fresh layer of “Barolo” (like the red wine) carpet so they could be topped with new seats.

Volpatt stressed how his company recycled every bit of the hall it could, including the metal from the old seats. He personally cut swatches of deep red velvet from some of the seats and donated them to be made into a dress for Pittsburgh Earth Day’s Ecolution Fashion Gala set for June 5 this year at Carnegie Museum of Art.

While a few salvaged seats were given to donors or put up for sale, the old seats weren’t historically important, Simonetti says. She believes they were replacements made during an earlier restoration, probably in the 1970s, based on construction and design clues found by the work crews. That’s also when she thinks some workers discreetly wrote their signatures on top of the arch and organ. She notes that the hall had undergone a renovation around the 1920s, as well.

Changing With the Times

Simonetti stresses that this project isn’t a recreation of the hall at any given point in the past but a continuation of the story of sustaining the hall for the future. Change comes with that.

In fact, the hall’s exterior changed dramatically just 12 years after it was opened as part of the huge 1907 expansion of the Carnegie Institute complex. The exterior lost the twin Venetian towers on either side of its Forbes Avenue front (Andrew Carnegie hated them). Covered up were the hall’s original curved exterior walls, which still can be glimpsed from the basement; additions included the hall’s grand foyer that generations of Pittsburghers now love as an event space. The institution had to grow and move on.

The hall’s 1,530 new scroll-armed, steel and maple-stained plywood seats were made and installed by Ducharme Seating in Montreal, Canada. They still have the classic red (well, “Cordovan”) velvet upholstery, and those on the aisles of the orchestra level have ornate, antique-looking cast-iron aisle panels whose custom design was inspired by a pattern on the proscenium, Simonetti says.

As she explains, “The reality is, you have to work on things to preserve them. Our take on this project was to keep as much of the old as we could and not recreate something.”

It’s detailed, it’s complicated, and yet, “This is my dream project,” says the western Pennsylvania native, who says she feels a responsibility to others for whom the hall is an important part of local life. “So it’s very humbling.”

Simonetti thoughtfully left her successors—whomever and whenever that may be—more helpful records than she had to work with. She even left them a “time capsule,” too. (The envelope of construction photos and “letters to the future” are on top of the arch, until it is found.)

“The reality is, you have to work on things to preserve them. Our take on this project was to keep as much of the old as we could and not recreate something.”

–Melissa Simonetti, director of construction and project management

In the meantime, she knows how passionate people are about this historic landmark. Those people include George Vosburgh, a retired principal trumpet of the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra who now is associate teaching professor of trumpet & wind ensemble studies at nearby Carnegie Mellon University, and director of the CMU Wind Ensemble.

The ensemble regularly performs at the hall, so he knows how hot it could be in summer and how “brutally cold” it gets during winter. But he appreciates how the original “state-of-the-art, no-expense-spared” music hall tends to make his young musicians sound much better than they do in the smaller, more “sound-bouncey” hall where they rehearse on campus. “It’s a beautiful, beautiful hall.”

Jeff Betten, who promotes Pittsburgh as a music city as owner of two indie record labels as well as a record manufacturing plant, said, “It’s one of my favorite venues in the city. The acoustics are impeccable, and I haven’t yet found that there’s a bad seat in the house when it comes to viewing the stage.” He loves how “grand it feels,” for not just classical music or opera but also a rock show. He cites a 2017 concert there by Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds—he was seated in the first balcony, stage center left—as “probably the best concert I’ve ever seen in my life.”

Vosburgh said he can’t wait for his students to perform there going forward. “This is what we do as musicians. We want to play in great spaces. And this is a great space.”

Nearly 50 donors contributed to the first phase of this historic restoration. Lead support has been provided by The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the Allegheny Regional Asset District (RAD), the Charles M. Morris Charitable Trust, and the Scott Foundation, Inc. Major support has been provided by Mr. and Mrs. Lee B. Foster, the Akers Gerber Family, Hilda M. Willis Foundation, and Christopher Fry.

The public is invited to support the Carnegie Music Hall renovation in a “Take Your Seat” campaign coming March 25!

Receive more stories in your email

Sign up