The RMS Titanic collided with that infamous iceberg near midnight on April 14, 1912, in the cold North Atlantic, scraping its starboard side along the jagged mass with such force it left an ominous streak of red paint. After six of its watertight compartments were breached and the incredible pressure of the uncaring sea split its bow from its stern, sending both plummeting through 12,500 feet of water to their final resting place some 400 miles off the coast of Newfoundland, Canada, there was nothing to do but wait.

Surviving passengers would suffer for hours waiting to be rescued. As for the ship, it would sit there untouched for more than 70 years, in two hulking pieces separated by a gulf of nearly 2,000 feet, its stern spun to face its bow like some melancholic statue pining for a partner.

When the dust settled—in this case, sea-floor silt with a pH more acidic than coffee—the Titanic was no longer a state-of-the-art technological marvel. It had become, instead, the world’s most famous shipwreck. In the process, the ship itself and the personal belongings of more than 2,200 passengers and crew became the remnants of a great floating city, left to decompose in the biting black waters at the bottom of the ocean.

After all that time, undisturbed, the ship’s location finally was identified in 1985. Along with its discovery came the realization that at those depths, decomposition is relative. Over the past four decades, through the efforts of oceanographers, explorers, marine scientists and conservators, many of those remnants have been brought back up to the surface and restored to the light to be seen and appreciated by future generations.

Now, visitors to Carnegie Science Center will be able to share in that experience by viewing more than 150 of the artifacts so carefully collected and preserved over time as part of TITANIC: The Artifact Exhibition, which runs until April 15.

“People love a good tragedy,” says Marcus Harshaw, the senior director of museum experiences at the Science Center.

But the exhibition is about much more than just the cultural weight that the Titanic carries. Through the history that fascinates people around the world, museumgoers can explore the science of oceanography, marine biology, and artifact conservation, all of which Harshaw hopes will inspire visitors, particularly children, to think more deeply about what lies beneath the surface of our oceans.

“We hope [young people] see themselves as possible scientists who are going to help tell either this story or other undersea stories. We know more about the surface of our moon than the floor of our oceans.”

–Marcus Harshaw, senior director of museum experiences, Carnegie Science Center

“We hope they see themselves as possible scientists who are going to help tell either this story or other undersea stories,” Harshaw says. Their help will be needed, he notes, because “we know more about the surface of our moon than the floor of our oceans.”

Turning Point and Time Capsule

After discovering the Titanic’s location on the first dive down to the wreck, in 1987, explorers recovered a leather bag with a pouch inside filled with more than 60 small vials. Each one was tucked inside its own capsule, a tiny glass bottle with a stopper still in place. The liquid they held had been preserved inside. Once conservators restored the collection and made its paper labels legible once again, they realized they were perfume samples brought aboard the ship by Adolphe Saalfeld, a German chemist and a salesman of scents. Remarkably, they were able to withstand the 6,000 pounds of pressure that bore down on every square inch at 2.5 miles below the ocean’s surface.

In TITANIC: The Artifact Exhibition, some of those bottles are on display in a case dotted with small holes, so visitors who get close enough can use the most transportive sense to capture a scent that’s survived an unbelievable journey.

Visitors will also be able to see postcards and playing cards that represent some of the most remarkable recoveries and restorations in the entire collection of 5,000-plus artifacts preserved by RMS Titanic Inc., the company that operates the traveling Titanic exhibitions around the world. Members of its team have completed eight expeditions to the shipwreck to map the area, recover the ship’s artifacts, and learn about the effects of the deep sea. They’ve learned, for instance, that organic materials like paper, textiles, wood, and leather that usually are more susceptible to deterioration than most other materials, found within leather cases and trunks, were miraculously preserved due to the relatively anaerobic conditions.

A collection of more than 25 au gratin dishes offers a window into another of the most peculiar discoveries from the shipwreck. Over time, the wooden cabinet or crate that once carried them deteriorated on the floor of the open ocean, but after conservation efforts the dishes look just as fit for use as they would have in 1912.

“You can still see the nice, neat stacks of au gratin dishes exactly as they landed,” marvels Tomasina Ray, RMS Titanic’s director of collections. “The way we can show their recovery versus what they looked like originally is important.”

To Ray, the artifacts that have been recovered from the shipwreck and carefully preserved over the past four decades offer a window into another time and a new way to think about our own.

“It was such a turning point in our culture, in terms of class and that age of hope and optimism and technology,” Ray says. “It’s a touch point that brings together culture, science, and the technology being developed at the time. You’re getting all of these things together in this one time capsule.”

Objects like the telegraph mechanism used to relay messages throughout the ship, a porthole through which passengers looked out onto the open sea, and a fuse plate that indicated the spread of electricity onto ocean liners—all of which are part of the exhibition—bridge the gap between eras and tell important stories about the evolution of science and technology, Ray notes.

As they view the artifacts in the exhibition, visitors take a chronological journey through the ship’s history, from its construction and its brief span on the seas to its sinking and the recovery of what it left behind. Each visitor receives a replica boarding pass with a real passenger’s name, bringing them into the Titanic story as they walk through first- and third-class cabins recreated as they looked all those years ago.

“It’s a touch point that brings together culture, science, and the technology being developed at the time. You’re getting all of these things together in this one time capsule.”

–Tomasina Ray, RMS Titanic’s director of collections

Just over 700 of the ship’s passengers survived, and visitors don’t find out until the end of the exhibition whether their counterpart made it or not. A simulated iceberg cooled to the same temperature of the water on the night the ship sank will give everyone a sense of what those passengers might have experienced while hoping to be rescued.

Buhl Planetarium is presenting the night sky as it looked that night. And the Science Center plans to host a 21-plus night on April 12, one of the days on which Titanic sailed more than a century ago, as well as screenings of James Cameron’s Oscar-winning 1997 film in The Rangos Giant Cinema.

Up From the Abyss

Titanic’s location in the ocean’s abyssal zone—where oxygen is nearly absent, temperatures are near freezing, darkness is absolute, and the water is acidified—is a dynamic agent in the degradation or preservation of artifacts, according to Rhonda Wozniak, the conservator on RMS Titanic’s 1994 expedition (see sidebar) and previously objects conservator at Carnegie Museum of Art. Before explorers began diving to the Titanic and bringing back pieces of its history, nothing had ever come back from so far below the ocean’s surface.

Once raised from such great depths, ceramic and glass will deteriorate if the salts that have seeped into their silica networks are allowed to crystallize outside of water, Wozniak explains. Cast iron brought up from the deep may appear to explode if exposed to the air before treatment, as corrosion products rapidly form where the metal core and graphitized outer layer meet. These realities make the work of conservation a pressing concern from the moment an artifact exits the water.

But these same hostile conditions have also allowed many of the objects strewn about the wreck site to last through the years, preserved by the cold, dark, and relative calm at such great depths. The condition of many Titanic artifacts has been influenced by another most unusual aspect of the deep sea: a new species of rust-eating bacteria, aptly named Halomonas titanicae.

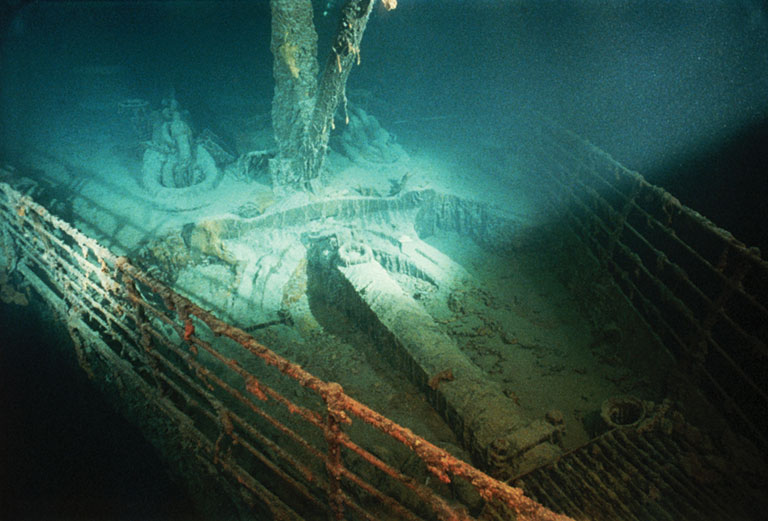

As it deteriorated, the ship was being covered by what have become known as “rusticles”—formations that resemble icicles or stalactites, spilling off of the Titanic into pillars as its iron became oxidized by microbes. Being surrounded by a mess of iron corrosion products can be detrimental to an artifact’s preservation, but proximity to the ship can also play a curious part in conservation, too.

The telegraph in the exhibition, for example, stayed in contact with the ship’s hull, whose iron offered the telegraph’s bronze structure galvanic protection. Meanwhile, another telegraph that had been thrown free from the wreckage was rapidly corroded by the sea. The ship’s rusting process will eventually lead to its complete destruction—all tens of thousands of tons of steel that made it such an icon.

The global fascination with the ship’s demise and the fates of the people aboard it has brought explorers down to the abyss and encouraged them to bring artifacts back up to land. Along the way, it’s advanced our understanding of portions of the world that remain relatively unknown.

David Gallo, a senior adviser at RMS Titanic who previously worked at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts, speaks to “the mystique of this grand ship and all it represents,” which makes its scientific value as significant as its cultural cachet.

“The Titanic,” Gallo says, “is a portal to get people interested in the bottom of the sea.”

The artifacts in the exhibition make that point clear, giving visitors a chance to connect to the people, such as the German chemist Saalfeld, who brought them on the Titanic, as well as the process by which they were raised from the deep and preserved.

“The people we have identified, you wouldn’t have heard about them otherwise,” Ray says. “They’d be lost to history. So we’re giving them a voice again, giving them a presence, keeping memories alive as much as we can, and reconstructing their stories.”