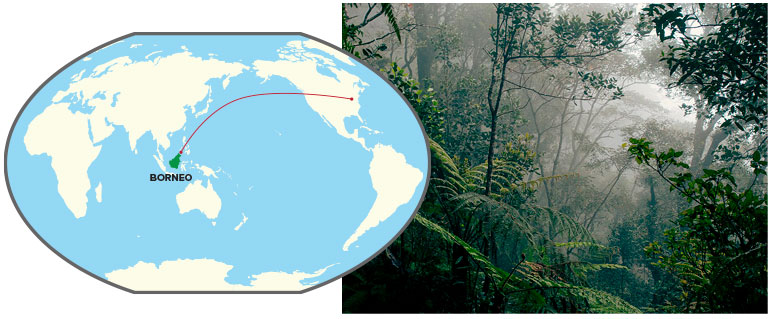

During the day in Sabah, Malaysia, flies and wasps buzz to and fro, birds such as the blue-headed pitta belt out their choruses, and langur monkeys whine in the treetops. But it’s when the sun sets that this rainforest really springs to life.

Every evening, a wall of noise unlike any other erupts out of the woodwork as nearly 3-inch-long giant cicadas begin to sing. In fact, the insects’ 100-decibel cacophony is so routine, some people know them by another name—the 6 o’clock cicadas.

It’s amid this jackhammer-level of sound that Jennifer Sheridan must begin her nightly quest to seek out tiny, camouflaged frogs, sometimes by eyeshine and other times using only the amphibian’s chirps and squeaks to zero in on its location. Bornean elephants and venomous snakes live here, too, so Sheridan must be wary as she works, picking her way carefully across slippery streams.

“If you’re out during the day, the elephants are kind of loud. They’re crunching things,” says Sheridan, associate curator of amphibians and reptiles at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. “But if you happen to stumble upon a sleeping herd at night, that could be dangerous.”

Despite the risks, the grueling travel (a 35-hour journey from Pittsburgh), the thin mattresses, and the stinging insects, it’s all worthwhile the moment Sheridan hears the cheep cheep cheep of the mysterious mud-brown toad she’d come to study.

On an earlier expedition to Borneo in 2023, Sheridan heard something in the night that didn’t make any sense. It was a three-pulse call, and it originated from a pebbly-skinned toad that’s brown on top and sandstone-colored on its underside. At first glance, it appeared to be an amphibian known as Ansonia longidigita. Except there was a problem.

“We heard this longidigita making a call that was not what we knew the call of longidigita to be,” Sheridan explains.

In fact, it wasn’t even close. Earlier recordings of the species, taken more than 100 miles to the southwest in Brunei, revealed that A. longidigita sings with a 12-pulse rhythm. But the frog in front of her was only belting out three notes in a row.

Photo: Kara Fikse

Photo: Kara FikseA new call could mean that this was a new species for the Mahua area. Or it might have meant that the frog back in Brunei was previously misidentified. Finding the answer was important, Sheridan says, because understanding an area’s true biodiversity is critical if you’re trying to help save it.

“You can’t conserve what you don’t know is there,” she says. “We need to have baseline information before we can assess effects of climate change or environmental degradation.”

Unfortunately, because the 2023 outing was focused on recording, not collecting, Sheridan didn’t have the proper tools on hand to take the frog as a specimen, which could have allowed her to solve the mystery.

And so, Sheridan traveled to Borneo again this past October on a Carnegie Museum of Natural History-sponsored expedition. To aid her in this pursuit, Sheridan was accompanied by Kara Fikse, director of donor engagement and stewardship for Carnegie Museums, who not only helped document and publicize the outing but also served as Sheridan’s field assistant, learning how to preserve and fix samples that would ultimately go into the museum’s herpetology collections.

Their goal: to collect specimens, record frog calls, and solve the mystery of the three-note frog.

“You can’t conserve what you don’t know is there. We need to have baseline information before we can assess effects of climate change or environmental degradation.”

–Jennifer Sheridan, associate curator of amphibians and reptiles, Carnegie Museum of Natural History

As a community ecologist, Sheridan focuses her research not just on frogs but also on how frogs interact with each other and their environments, and how those interactions are changing over time.

Sheridan says frogs are a perfect study organism—and not just because they don’t constantly peck and bite at you, like the birds she studied for her master’s degree.

For starters, frogs can be found in great numbers across a variety of ecosystems. So when Sheridan visits a place like Borneo, she knows she’ll always come away with a healthy number of observations, recordings, and samples. The same can’t be said for researchers who study larger or more difficult-to-spot creatures, such as marine mammals.

“In ecology, an important factor is having strong sample sizes. If you have small sample sizes, it’s hard to get statistical power,” says Sheridan.

The other neat thing about frogs? Their calls are what’s known as a reproductive isolating mechanism—“which means that a frog of a given species will only respond to the call of that same species,” says Sheridan. “And so you can use this to help define species.”

In Love with Frogs

A lot of herpetologists—scientists who study reptiles and amphibians—talk wistfully about childhoods spent catching frogs, chasing snakes, or raising turtles.

“That was not me,” Sheridan admits. “I loved animals as a kid, for sure, but when I was really little, I lived in Detroit, and those animals did not exist in my neighborhood.”

Rather, it wasn’t until her third year of undergraduate study at the University of Chicago that Sheridan would take an ecology class that thrust her into a study of amphibians in the forests around northern Illinois.

“I remember going out to these ponds, setting out minnow traps, and then going back the next day, and they were full of blue-spotted salamanders or these big, giant tadpoles,” she says. “And that was the first time I remember thinking to myself, ‘I can’t believe I’m getting paid to play with animals.’”

A year later, after graduation, Sheridan signed on to spend six months working as a field assistant to a PhD researcher studying Bornean frogs.

“It was the greatest six months of my life,” she says. “And that is how I fell in love.”

Photo: Kara Fikse

Photo: Kara FikseSheridan has now been to Borneo more times than she can remember, sometimes making several trips per year, going back to 1996.

“My mother always asks, half-jokingly, ‘Why can’t you study frogs here? Why do you have to go so far away?’” laughs Sheridan. “But the tropics hold the majority of terrestrial life on Earth, and yet we know the least about them.”

As an example, she points to a study published in the journal PLOS ONE in 2010 that tallied up just how many species of tree live in the Ecuadorian rainforest. And not even the whole Ecuadorian rainforest, or a large section of it, but an area only about one-quarter the size of Pittsburgh’s Shadyside neighborhood. Amazingly, this sliver of the tropics contained 1,100 species of trees, which is more species than exist in the entirety of the United States.

“The tropics hold the majority of terrestrial life on Earth, and yet we know the least about them.”

–Jennifer Sheridan, associate curator of amphibians and reptiles, Carnegie Museum of Natural History

And it’s much the same story with amphibians. For instance, around 180 species of amphibian call the island of Borneo home. The vast majority of them are endemic, which means they are found nowhere else on Earth.

“Everything in the temperate region is very well studied compared to things in the tropics,” says Sheridan.

The Importance of Frog Calls

Frog calls are not set in stone.

“Some species only make one type of call. Others have several different call types,” says Sheridan.

To complicate matters further, the call of a given species might change based on environmental factors, such as temperature or elevation. This bit is particularly important when it comes to human-caused global warming, says Sheridan, because what was once representative for a certain species in a certain area may now be different, all because the climate is changing.

Humans can also affect frog calls through our noise, she notes. For instance, in at least one frog species, an experiment revealed that when traffic noise is played, the animals will start calling louder as a way to compensate. Similarly, other research has shown that animals may change the frequency at which they call when confronted with anthropogenic noise. But behavioral adjustments come at a cost.

“Frogs are going to have to either consume more resources to maintain their body size, for example, or they might ultimately not grow as big if they’re putting all this energy into calling that they could have previously put into growth and maintenance,” Sheridan explains.

Prior to this most recent Borneo trip, Sheridan didn’t yet have the data she needed to solve the mystery of A. longidigita. She couldn’t determine if the different calls were actually separate species or if the species might simply have more calls in its vocal repertoire than anyone has ever documented before.

In the end, there was only one way to learn the identity of every crooner in the night. She needed to collect recordings and specimens.

A Headlamp and a Whole Lot of Questions

Surveying amphibians in a rainforest doesn’t require massive nets like researchers use for capturing birds or bats, nor does it call for rock-cutting power tools, like in paleontology fieldwork. The most important tools are hand-held audio recording equipment and a good headlamp.

“We spent most of our time in the rainforest, and to add to the usual challenges of fieldwork, it was night,” says Kara Fikse, who assisted Sheridan on the trip. “Every once in a while, I would turn off my headlamp just to get that full sense of immersion in the darkness.”

Photo: Jennifer Sheridan

Photo: Jennifer SheridanFikse marvelled at Sheridan, an experienced nocturnal navigator. She remembers watching in awe as Sheridan spotted tiny tadpoles attached to a rock as they were crossing a stream, or the way she pinpointed the call of a distant frog in the pitch-black. And she says she’ll never forget when Sheridan lifted up a frog and told her to “take a whiff” of the amphibian’s toxic, tangy perfume.

“I never thought I’d be sniffing a frog,” laughs Fikse.

“I think amphibians make great systems for this sort of work as they are great sentinels of environmental change. So by tracking their health, disease, microbiome, or evolution, they may serve as indicators for other things happening on the landscape.”

–Kevin Kohl, animal physiologist and microbial ecologist at the University of Pittsburgh

In all, Fikse and Sheridan spent two weeks wading through streams, recording equipment in hand. The duo managed to record the calls of 11 species of frog, several of which will be new to the scientific literature. They also collected and preserved 76 specimens.

Photo: Kara Fikse

Photo: Kara FikseEleven species will be entirely new for the museum’s collection, and several had never been seen by Sheridan before. These included several specimens of a large frog known as the Kinabalu horned frog (Xenophrys baluensis), which comes in various shades of mottled red and looks like it would disappear in a pile of fall leaves.

While Carnegie Museum of Natural History already houses 81,794 frog specimens, every new addition holds value. For instance, many outside researchers use the collection to study an array of topics.

“I think amphibians make great systems for this sort of work as they are great sentinels of environmental change,” says Kevin Kohl, an animal physiologist and microbial ecologist at the University of Pittsburgh. “So by tracking their health, disease, microbiome, or evolution, they may serve as indicators for other things happening on the landscape.”

Three Notes in the Night

But what of Ansonia longidigita, the mystery frog by which the success of Sheridan’s recent Borneo expedition would be measured?

“We were walking along a trail and I heard a sound I couldn’t immediately identify,” remembers Sheridan.

Realizing it was coming from the stream nearby, she quickly but carefully made her way down to the water, then backtracked downstream to where she’d first heard the sound. After several minutes, she spotted it—a frog of the Ansonia genus, sitting on a branch about 3 to 4 feet above the water. The frog began to sing again, at which point Sheridan got the recording and steeled herself for the last step.

Photo: Kara Fikse

Photo: Kara FikseOne mistake and the amphibian would leap into the water and disappear, leaving what’s known as the “extended specimen” incomplete.

It’s not enough to spot a frog, or even to record it singing, if you can’t collect the animal. It’s critical that the same animal that produces the song is included in the specimen. Without that, you can’t prove identity, or compare that identity against other animals already in the collection. An extended specimen might contain different things depending on what kind of organism you’re trying to document, but for frogs, Sheridan likes to include not just the animal, but also its precise location, DNA, and audio recording.

“I recorded it for several minutes, and even though it was a bit high to reach because I was standing knee- to thigh-deep in water and the bedrock was steep and slippery, I managed to get it before it jumped away,” Sheridan exclaims. “Success!”

Photo: Kara Fikse

Photo: Kara FikseBut exporting exotic frog specimens from halfway around the world is a complicated process, and not all of the materials have arrived back in the United States. So it will be a few months before Sheridan will know whether the frog she caught was actually A. longidigita or perhaps a new species. It’s also possible that by comparing the new call data with that from the specimen in Brunei, she’ll be able to describe an entirely new call for A. longidigita.

“This is still a work in progress because the export permits came through after I left Borneo,” says Sheridan. “So once we get the materials back here in the U.S., I can confirm the identification genetically and then solve the mystery.”

Her best guess? Sheridan suspects the frog she caught is the true A. longidigita, and the individual captured in Brunei is an as-of-yet-undescribed species.

Once Sheridan has the extended specimen of A. longidigita in hand, the mystery of those three chirps in the night should unravel nicely. But there will always be new questions to answer, new biodiversity to discover and explore.

“As scientists, we are sort of trained that it’s never enough,” says Sheridan. “So I struggle with thinking, ‘Oh, it was a success,’ versus, ‘If only there had been better weather on a couple of nights, or if only I had more time, I could have gotten more!’”

Receive more stories in your email

Sign upTags:

Science & Nature