Visitor favorites for sure, the nearly 1,900 specimens on display in Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s Hillman Hall of Minerals and Gems are dazzlingly diverse, and many qualify as rare. The museum’s renowned mineral collection boasts more than 31,000 specimens in all, many of which were acquired back in the 19th century. It includes a rare suite of minerals from the former Soviet Union and the most comprehensive Pennsylvania mineral collection in the world, which includes more than 2,200 historically important specimens from the William W. Jeffries collection, nearly 5,000 minerals formerly owned by the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, and more than 2,700 acquired from the Bryon Brookmyer collection.

So, what makes a mineral rare? “There can be more than one way to define it,” Collection Manager Debra Wilson says. “For example, if it’s found in only a few places in the world, or maybe just one. Some mineral species rarely form as crystals, or rarely occur in certain colors.”

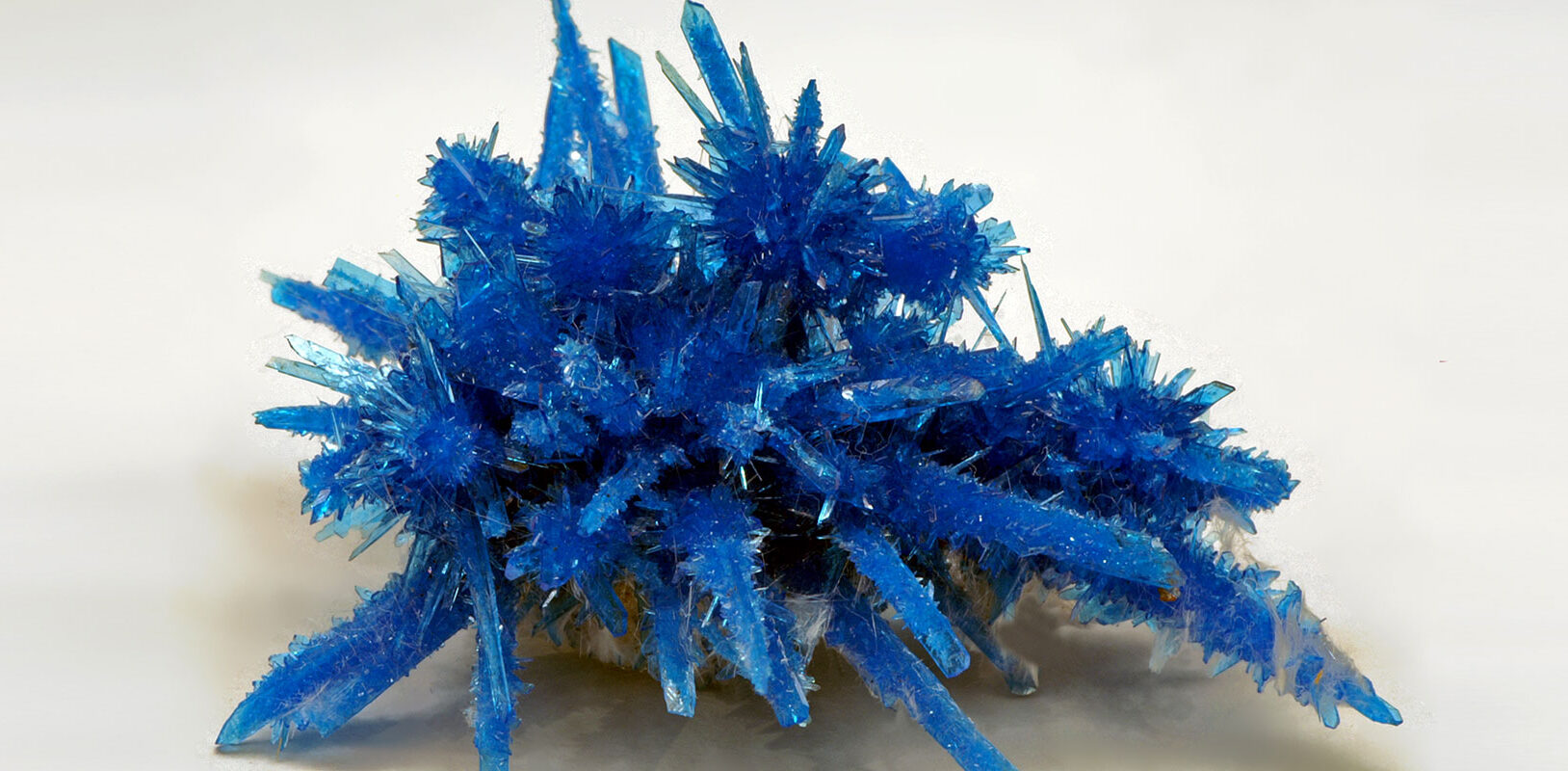

When asked about the rarest minerals in Hillman Hall, Wilson points to two related species unearthed over the past few decades by workers in the Wagholi quarries in the Pune district of Maharashtra, India. Immediately distinguishable by their brilliant blue color, pentagonites and cavansites look a lot alike and have the same chemical formula, but their varying molecular structures technically make them two different mineral species.

Wilson explains that between 60 and 65 million years ago, nearly one-quarter of India was covered by thick volcanic flows of basalt. Today, these rocks form the Deccan Plateau, which is rich in a group of minerals known as zeolites. The modern-day excavations of the land for roads, tunnels, building foundations, stone quarries, and wells in India’s Maharashtra state—situated atop the Deccan Plateau—have produced rare crystals of zeolites and related minerals such as those on display in Hillman Hall. What makes the pentagonite and cavansite specimens so rare? “You won’t find them as high-quality crystals like this anywhere else in the world,” Wilson says.

The museum has four pentagonite and five cavansite specimens in its India collection, and five are on public view in Hillman Hall display cases. All were purchased through the efforts of the former head of the section of minerals, Marc Wilson (Debra and Marc are married), who retired in 2017 after 25 years.

According to Debra Wilson, the rarer of the two species of minerals formed millions of years ago in India’s Deccan Plateau is the pentagonite, named for its five-fold symmetry. And the pentagonite specimen on display in Hillman Hall’s India display, she says, is perhaps, “the best in the world.”

What are you curious about?

We’ll investigate what you’ve always wanted to know about the four Carnegie Museums. Write to us at carnegiemagazine@carnegiemuseums.org.