You May Also Like

A Weighty Conversation In Celebration of Artists and Their Truth Art in ContradictionI think my work will feel something like this, Alex Da Corte wrote to curator Ingrid Schaffner about his project for the Carnegie International, in reference to a 1970s photograph of Sesame Street puppeteer Caroll Spinney. In the image taken on set, Spinney is on his knees operating Oscar the Grouch while wearing the bright-orange feet of Big Bird.

“I wanted to capture this back door/front door, funny/sad, inside/outside,” Da Corte recalls. “I thought now is the time to make a portrait of the place I live.”

Visitors explore Alex Da Corte’s neon creation. Installation view of Alex Da Corte’s Rubber Pencil Devil, 2018, Courtesy of the artist and Karma Gallery. Photo: Bryan Conley

The Philadelphia-based artist is known for building wonderfully weird worlds of neon, and the one he made for Pittsburgh is epic and absorbing. The frame of a house rises out of aluminum and artificial light, its windows adorned with holiday emblems and electric-pink tulips in flower boxes. The inside glows with friends from childhood: Pink Panther, Popeye, Sylvester the Cat, and Bugs Bunny bellowing a Frank Ocean cover of “Moon River.”

Da Corte is artist, actor, filmmaker, and costume designer for the 57 video shorts running in a continuous three-hour loop inside his colorful creation. He stars as nearly every character, and along with his team made all of the sets and costumes. “Even Mister Rogers’ khaki pants,” he notes.

In a particularly poignant moment, the artist walks slowly through the door of a familiar-looking living room. He’s dressed as Mister Rogers in a brightly colored cardigan, smiling into the camera as he sits down to change his shoes. Soon, he’s out the door and back in again, repeating the ritual in slow motion, in a different colored sweater, again and again.

The structure of the videos is inspired by Bob Dylan’s Subterranean Homesick Blues, a song about another tumultuous time in the country’s history, and its promo clip, during which Dylan cycles through key phrases using notecards. In Da Corte’s performances, there are words of indictment against the American government as well as hidden references to his grandmother’s dementia.

“Painting, culture, pop culture, Alex brings it all together in plain sight, but at the same time hidden from view,” says Schaffner. “There is a sort of casualness or Pop to his work that maybe belies the depth and seriousness of it, but you only need to spend a little bit of time to understand that it’s complex.”

A series of stills drawn from the 57 video shorts that play on a continuous loop inside the neon house.

Da Corte’s visual feast delivers in spades on Schaffner’s goal of inspiring museum joy, an act she defines as the “commotion of being with art and other people actively engaged in the creative work of interpretation.”

Especially now, in the wake of the October 27 tragedy that claimed 11 lives in the heart of Pittsburgh’s Jewish community, Mister Rogers’ real-life neighborhood, joy as a kind of resistance is more urgent than ever.

A language of the land

“Abel Rodríguez is a ‘namer of plants’ who would not necessarily identify as a contemporary artist,” says Ingrid Schaffner. “He learned the language of drawing to transmit knowledge that might otherwise be lost.”

An indigenous elder of the Nonuya people from the Caquetá River region of Colombia, once a community of farmers located not far from the Amazonian rainforest, Rodríguez was reared to know the natural world. You can see it in his lush botanical drawings rendered in shades of green and brown, with rivers of blue occasionally winding through them. At first glance, groups of images look similar, but gradual differences emerge, reflecting seasonal changes: a tree blossoms, fish and turtles fill the river and then disappear; river water rises and recedes.

Photo: Bryan Conley

His knowledge comes from observation and oral traditions. When scientists traveled to the region to do field research, they hired Rodríguez as a guide. Then, in the 1990s, guerrilla violence forced out foreigners and locals alike, and Rodríguez and his wife fled to Bogotá. With few options for earning a living, he reached out to one of the scientists. The director of Tropenbos International Colombia, a Dutch NGO dedicated to the study and protection of tropical rainforests, asked Rodríguez if he would continue teaching them, this time on paper. Rodríguez started making drawings in 1999. And because he has not returned to the forest since, all of the information he imparts is drawn from memory. “I had never drawn before; I barely knew how to write. But I had a whole world in my mind asking me to picture the plants,” Rodríguez said in an interview with the NGO.

Abel Rodríguez, Ciclo anual del bosque de la vega (Seasonal changes in the flooded rainforest), 2009–2010, Courtesy of the artist, Tropenbos International Colombia, and FLORA ars+natura, Bogotá, Colombia

On display in the International are representations of Rodríguez’s larger body of work that Schaffner says she selected to give “a sense of the scope of Abel’s investigation.” In some drawings, he includes written information such as the color and taste of bark and descriptions of crops and which animals feed on them, both in his native Muinane language and in Spanish. All of it flowing from an initial prompt: Draw what you know.

Timeless beauty

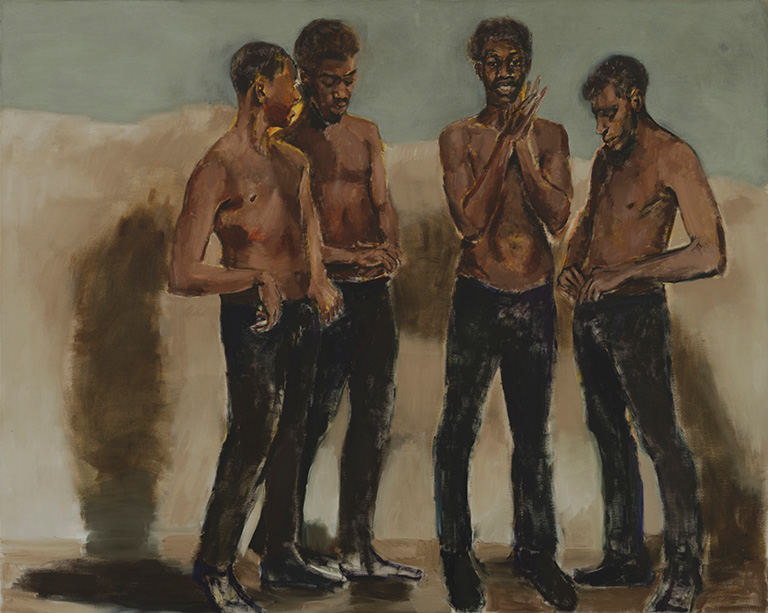

Painter Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s installation of 13 striking, dreamlike portraits earned her the Carnegie International’s prestigious Carnegie Prize, which includes a $10,000 award and the Medal of Honor, first issued to Winslow Homer at the 1896 International.

The British-Ghanaian artist made a model of the gallery space for reference, says Ingrid Schaffner, and requested that its walls be painted a color named magnolia. “You can see how much she was thinking staging. Look, for instance, at the painting of the two figures—facing each other, squatting like dancers about to spring on some tacit signal—and at how the corners of the background are painted that same magnolia color, essentially dissolving the canvas and releasing the figures into our space.”

Photo: Bryan Conley

Like all of Yiadom-Boakye’s works, her figures are fictional characters painted from her imagination, composites from a variety of sources, including her own drawings. Composing directly on linen, the artist consults scrapbooks of materials as she works, and takes just a single day to complete a painting.

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Amaranthine, 2018, Courtesy of the artist, Jack Shainman Gallery, New York and Corvi-Mora, London

“Some figures feel almost historic in pose—or painting reference,” says Schaffner. “Others feel absolutely contemporary as if seen in a fashion shoot. At the same time, there really aren’t any fixed temporal cues so that the works slip into and around the present moment.”

The paintings relate to the artist’s writing, which includes vignettes, fables, and short stories. “Some of her portraits feel similar to a scene from a play or a film, others like a full-on episode,” Schaffner continues. “Sometimes something very specific is happening, other times it’s an abstraction. There’s an intentional lack of continuity. She didn’t make one person, one moment, one story. That’s what makes it such a rich installation. Each is offering its own terms.”

Coming for you

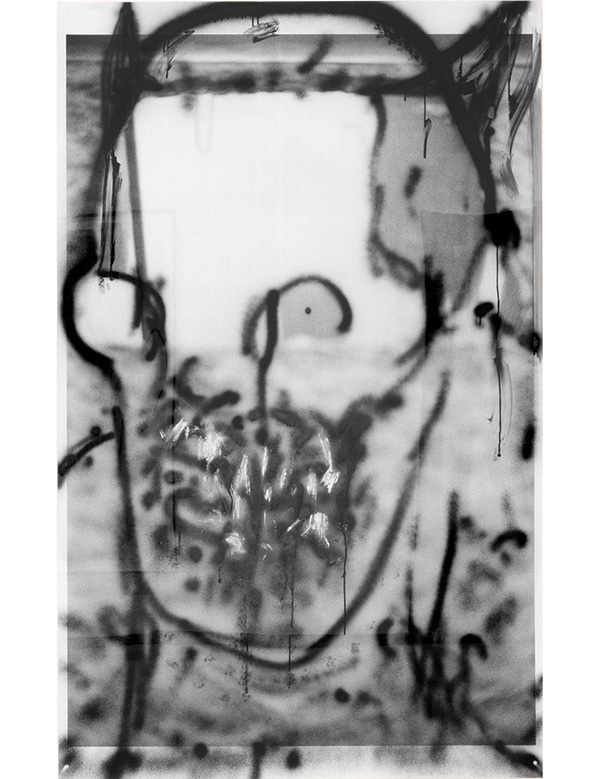

Looming large in the Heinz Galleries is Huma Bhabha’s 12-foot-tall sculpture crafted out of cork, a giant tree branch, Styrofoam, and clay on chicken wire. The figure should feel right at home in the museum, says Ingrid Schaffner. “Carnegie Museum of Art’s collection is characterized by a deep humanism and commitment to figurative art,” she says. “Bhabha’s work is in conversation with so much art that is here. Her sculpture could stroll on down the corridor to have a chat with Giacometti’s Walking Man.”

But is it man or monster? Is it from this world or the next? “I prefer to leave it open-ended so that you can imagine whether the skin is stripped off, or whether it’s an addition,” says the Pakistani-American artist who, for six months this year, had a pair of her monumental sculptures installed on the roof of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Installation view of Huma Bhabha’s sculpture Memories of the Future, 2018, Courtesy of the artist and Salon 94, New York. Photo: Bryan Conley

Her figure for the Carnegie International is made of cultural materials, natural resources, and objects of the Anthropocene. “I think of it as a presence calling a lot to it from the museum,” says Schaffner, noting how ethnographic objects are typically relegated to the part of the building that houses the Museum of Natural History.

Two large-scale drawings that Bhabha makes on photographs hang on each side of her towering creation, functioning as a kind of apocalyptic backdrop. “The drawings are powerful images in their own right,” Schaffner says, “composed with masks, with eyeholes, and animal faces that stare back at you.”

Huma Bhabha, Untitled, 2018, Courtesy of the artist and Salon 94, New York

Miniature still lifes

Every day for more than 30 years, Yuji Agematsu has taken a walk in his adopted city of New York to pick up the tiny leftovers of life—used chewing gum, dental picks, dead bugs, cotton swabs, candy wrappers, chicken bones, hair wrapped around a lollipop, hair stuck to tape. He saves and meticulously records everything he finds.

Back in the studio, he assembles the day’s finds within cellophane sleeves stripped from cigarette packs. He also logs his journey, mostly in Japanese and complete with hand-drawn maps—first in notebooks, and then in his archives, where the objects may sit for years before reaching the status of art. Decay plays a beautiful role in his work.

Installation views of Yuji Agematsu’s zip: 01.01.17…12.31.17 (detail), 2017, Courtesy of the artist and Miguel Abreu Gallery, New York. Photos: Bryan Conley

His structures are tiny terrariums, no two alike. Some are messy and overflowing, others exact and sparse. Sometimes gross and always enchanting, they’re a fascinating way of marking time and place. The bits of detritus “decide on their own comfortable positions,” Agematsu recently told ARTnews. “My duty is just to help fix them in place.” The artist moved to New York City from Kanagawa, Japan, in 1980, and to get to know his new home he set out on foot; he’s been walking and collecting ever since. On view in the Charity Randall Gallery are 365 packs he made last year, organized in glass cases, each one representing the days and months of the calendar year. And in a case just outside the gallery, the artist displays tiny flakes of artworks that Carnegie Museum of Art conservators have preserved in ziplock bags over the course of years. Exhibited above and below them: rainbows of perfectly preserved used chewing gum that at first glance resemble glistening displays of gems and minerals.

Receive more stories in your email

Sign upTags:

Carnegie International