You May Also Like

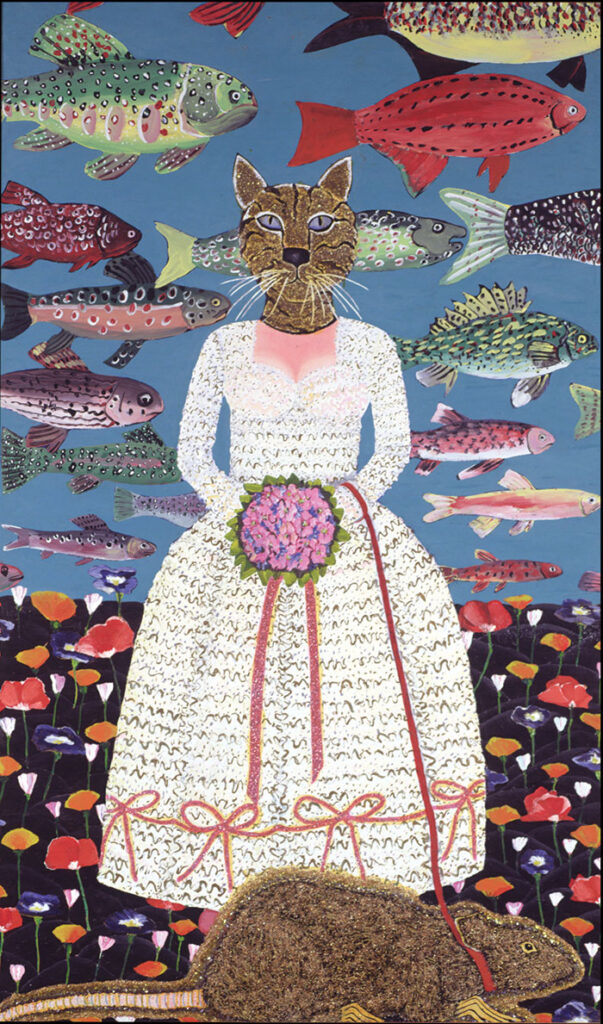

Visions for a Better World The Consummate Friend and Volunteer Creating Belonging Through ArtThe bride stands holding a bouquet of pale purple flowers at her waist, ribbon tied into loose bows along the bottom of her lace gown. She may be waiting for her spouse, who is nowhere to be seen as she poses in a black field studded with orange, red, and blue poppies. Behind her, a school of large fish swims past in a wash of turquoise—or are they flying?

She holds a leash, keeping the reins tight on a rat pulsing with glitter, a presence made more curious by the fact that her face is a cat’s, all sharp ears, piercing eyes, and faint whiskers. The bride is Joan Brown—or at least some representation of her—and she stands tall at the center of this life-size canvas, nearly 8 feet by 5 feet of bold, inquisitive self-portraiture.

Brown painted The Bride in 1970, and a half-century later it’s one of the first artworks visitors to Carnegie Museum of Art see when they encounter the first major survey of her career in more than 20 years, now on view in the Heinz Galleries. It’s a fitting welcome to Brown’s world, capturing her penchant for absurdity and introspection alongside her fascination with animals, both human and otherwise.

Over the course of a three-decade career that began when she burst onto the scene in the late 1950s and ended when she died tragically while installing an artwork in 1990, Brown lavished her attention on the everyday—her pets, her son, her hobbies, and, perhaps most of all, herself. But beyond her hometown of San Francisco, she did not quite become the household name that her early success anticipated, setting the stage for a timely reconsideration of her work.

“There’s a new receptivity in both the art world and the broader visual world to work like this: work that is figurative, work made by a woman, work that focuses on portraiture of herself, of the people around her, of available domestic objects—things that haven’t been seen in the history of Western painting as traditionally grand and worthy of large-scale paintings,” says Nancy Lim, associate curator at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, where the retrospective first showed this winter.

The Bride showcases some of Brown’s most familiar subject matter, as well as the playful personality and bright fields of color present in so much of her painting. In its sphynx-like blending of woman and cat, it also nods toward the interest in Egyptian visual culture and Eastern religion that inspired Brown’s search for expression through art.

“There are all these wonderful, whimsical moments we can read into with great seriousness, but it’s also so generous in how it is presented to our audiences,” says Liz Park, the Richard Armstrong Curator of Contemporary Art at Carnegie Museum of Art, of the painting. “I find it to be an incredibly welcoming image to start off the exhibition.”

Elevating the Familiar

Brown took time developing the colorful, diaristic style that makes so much of her work “digestible,” if not easy to consume, as Lim describes it. In her early years, after studying at the California School of Fine Arts (now the San Francisco Art Institute), her canvases were heavily impastoed—thickly layered and revealing each brush stroke—carrying the substantial weight of both her material and her interest in the mundane objects around her. Art critics compared her textured surfaces to a roller coaster.

Elmer Bischoff, her first painting instructor and one of her most significant mentors, seemed uncertain what to make of Brown, telling another artist, “She’s either a genius or very simple.” In the end, he may have been right on both counts.

With Bischoff’s encouragement, Brown learned to paint whatever and however she wanted. In 1959, she made Thanksgiving Turkey, in which the namesake perches precariously, limbs outstretched, on the edge of a table before a background of shifting green tones. The painting—an homage to Rembrandt’s The Slaughtered Ox—was acquired by the Museum of Modern Art in New York the following year, when Brown was 22, affirming both her style and her work’s substance. By elevating familiar subject matter, Brown’s art offers audiences a variety of entry points for inquiry, including her womanhood.

“Even though Joan herself would not have waved a feminist flag—as many women artists of her generation did not—I do think that monumentalizing the everyday and the domestic and the personal is an important act for thinking through feminism today,” Park says.

If her early success established a path for Brown to follow, she wasn’t interested in following it. Instead, she entered into what Lim calls “an antagonistic and uncomfortable relationship” with the art market that persisted throughout her career. She split from her dealer and began devoting her work to scenes from her daily life—often featuring her son, Noel, and various family pets; frequently referencing work from masters including Picasso and Goya. By the late 1960s she had begun painting in the flat, graphic style that is now most recognizable as hers—nevermind that it ran counter to what the art world wanted from her.

“She understood that was the only way she could go about it,” Lim says. “She could not live any way other than to define for herself what kind of painter she was going to be.”

“Even though Joan herself would not have waved a feminist flag—as many women artists of her generation did not—I do think that monumentalizing the everyday and the domestic and the personal is an important act for thinking through feminism today.”

– Liz Park, The Richard Armstrong Curator Of Contemporary Art At Carnegie Museum Of Art

When she ran out of paint while living in a small California town in 1970, Brown went to the local hardware store in search of a solution. She picked up cans of enamel—typically used to paint house exteriors—and stumbled into the material that would coat the most iconic canvases of her career. Smooth and flat in texture and brazenly vibrant in its palette, enamel allowed her to create paintings like Self-Portrait with Fish and Cat, an 8-foot-tall piece in which she stands in her painter’s clothes, a brush in one hand touched with the same yellow that graces the belly of the enormous fish bent elegantly back in the crook of her other arm. The background is painted a stark, bright, textureless red. A cat ambles past her feet—perhaps one of the many she cared for throughout her life.

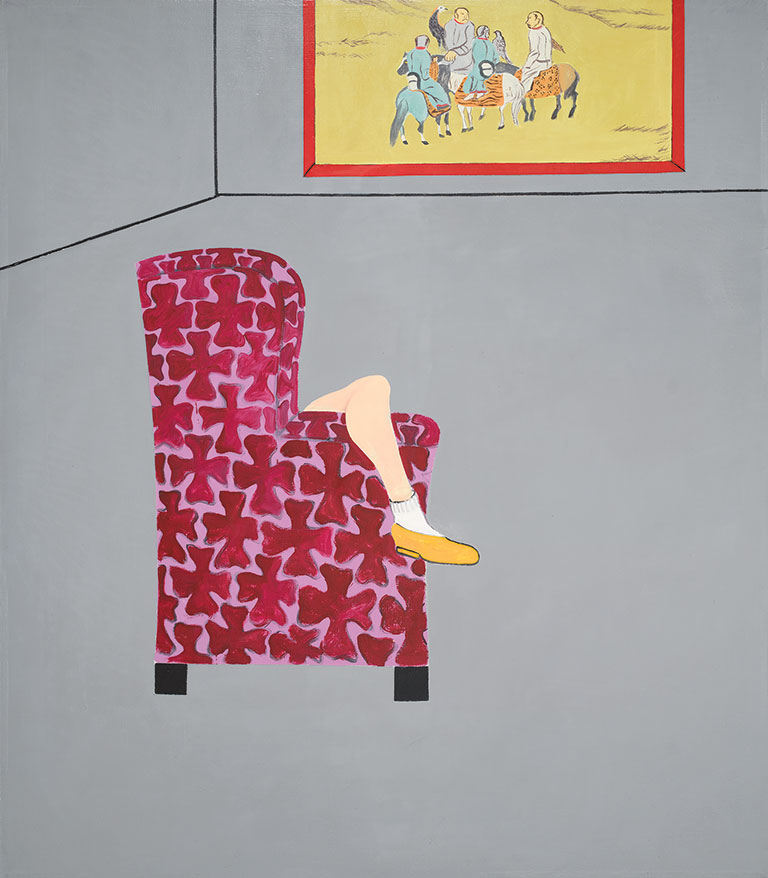

In another standout from the retrospective, The Room, Part 1, from 1975, a woman sits in a patterned armchair, facing the back of a stubbornly gray enamel room. A leg thrown casually over the side is the only piece of Brown visible as she faces the back of the room, where a ninth-century painting by Hu Gui, depicting Khitan tribesmen hunting with eagles, hangs in the distance. It’s the only one of Brown’s paintings that is part of the Museum of Art’s collection, and it highlights the ways in which she weaved art history into her work. Images of some of Brown’s references, both renowned and obscure, are sprinkled throughout the exhibition, so audiences can contemplate how her paintings balance superficial satisfaction with subtle depth.

“They’re very appealing and seductive, but at the same time so layered with meaning and references to historical painters, paintings she was drawing from, references to her personal life, and the kind of symbols she was folding into the work she was making,” Lim says. “All of that merged to create these very iconic paintings.”

Spiritual Contemplation

Brown’s work throughout the 1970s was studded with tributes to her love of dance and open-water swimming, as well as romance and its demise. (She married four times.) But at the end of the decade, she made another transition.

Following a visit to Egypt, she began more fully invoking the images and symbolism of ancient cultures, while also exploring her spirituality through art. She painted from meditative visions and dreams, seeking to apply the clarity she discovered in the teachings of her guru, Sathya Sai Baba. In 1980’s The Fan (Homage to Sai Baba), a warm orange background trains the eye on the four whirring blades of a ceiling fan and the switch controlling it. The simplicity beckons contemplation.

“They’re very appealing and seductive, but at the same time so layered with meaning and references to historical painters, paintings she was drawing from, references to her personal life, and the kind of symbols she was folding into the work she was making.”

– Nancy Lim, Associate Curator At The San Francisco Museum Of Modern Art

The shifting tides of Brown’s career make it all the more meaningful to consider a broad swath of her painting, and the retrospective features nearly four dozen of her pieces, including self-portraits that span the decades.

“It’s incredible to see an artist growing, changing physically but also changing her artistic style, her painterly style, her techniques, and how she wants to represent herself,” Park says.

In 1990, Brown visited a museum in Puttaparthi, South India, dedicated to Sai Baba, to install a 13-foot obelisk she had made as part of one last shift in her work— away from painting and toward public art and sculpture. In the process, a concrete turret collapsed in the museum, killing Brown and two assistants and destroying the obelisk. It was a tragic and unexpected death for a woman and artist who was still in the midst of a lifelong evolution.

“Joan Brown was a searcher, somebody who was always looking for something,” Park says. “She was looking toward her immediate environment and looking toward herself.”

In the catalog accompanying the retrospective’s presentation in San Francisco, Lim identifies the tension at the heart of any consideration of Brown’s work. Her paintings “exude an easy charm but were in fact an earnest means of introspection: portraiture that served to profoundly deepen knowledge of herself and others,” Lim writes. In her work, she sought to “crack open her psyche, as well as endless facets of the human experience.”

Visitors to the retrospective will have a chance to engage with an artist whose work was monumental in every sense—often in its scale and always in its attempt to serve as a tribute to and exploration of the objects, animals, and ideas that occupied Brown’s mind. In so doing, audiences might replicate her own practice of close observation, carrying on the search for intellectual and spiritual understanding that Joan Brown poured onto every canvas.

Joan Brown is organized by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. The exhibition is curated by Janet Bishop, Thomas Weisel Family Chief Curator and Curator of Painting and Sculpture at SFMOMA, and Nancy Lim, Associate Curator, Painting and Sculpture, SFMOMA. Carnegie Museum of Art’s presentation is organized by Liz Park, Richard Armstrong Curator of Contemporary Art at Carnegie Museum of Art with Cynthia Stucki, curatorial assistant for contemporary art and photography.

Significant support for the exhibition has been provided by the Susan J. and Martin G. McGuinn Exhibition Fund.

Carnegie Museum of Art’s exhibition program is supported by the Carnegie Museum of Art Exhibition Fund and The Fellows of Carnegie Museum of Art.

The exhibition closes on Sept. 24, 2023.

Receive more stories in your email

Sign upTags:

Art