Off the far northeastern coast of England, the tidal island of Lindisfarne feels unspeakably remote today: a lonely place of wind-swept dune grass, sea birds, and ancient ruins. At the end of the eighth century, however, it was the epicenter of European art and culture.

The wooden buildings of its monastery belie the fact that for over 150 years it had been plugged in directly to the power politics of England’s most formidable kingdom. It was connected, cosmopolitan, and consequential. The place was filthy rich. And it was undefended.

Vikings sacked Lindisfarne in the year 793, crashing onto the historical scene in a big way.

They looted the monastery and burned it; they killed some of the inhabitants and hauled others off to be sold into slavery. It likely all happened in an afternoon, the early medieval equivalent of a smash and grab. The news traveled fast. Imagine if Harvard University were razed tomorrow, Harvard Yard in embers, professors dead, students missing, and much of the $50 billion endowment gone. It was like that—except it was just the beginning. Vikings would proceed to terrorize and transform Europe over the next 250 years.

The men, and possibly women, who jumped out of the boats at Lindisfarne and splashed up the beach and into history that day were almost certainly not what you imagine—and that’s part of the focus of an exhibition of Viking artifacts now at Carnegie Science Center through Labor Day.

“There are some really amazing and interesting things about the Vikings that people may not know,” says Jason Brown, the Henry Buhl, Jr., Director of the Science Center, and vice president of Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh.

VIKINGS: Warriors of the North Sea aims to bring visitors up close and personal with the people who transformed and still influence Western society.

When we talk of “eggs,” of “guests” or “gangs”; of being “ill” or “dying”; when we “haggle,” “kindle” a fire, or go “berserk,” we speak their language.

When we go to the movies or turn on the television, we encounter Thor, Bernard Cornwell’s The Last Kingdom, Vikings—even the popular CBS comedy Ghosts features a Viking.

“Vikings right now are very popular in pop culture,” Brown says, noting they tend to be depicted in a very specific way in the media. “But there was so much more to their culture.”

Fashionable Subversion

Vikings were also traders, craftsmen, artists, and explorers; they interacted with peoples across a vast expanse—from the pine forests of North America to the Eurasian steppes, from the volcanoes and glaciers of Iceland to the stone-paved markets and shaded palaces of Baghdad and Istanbul. They founded the city of Kyiv, Ukraine, and were formative in the development of Dublin, Ireland.

Their helmets did not have horns.

The exhibition shows how archaeology can tell big stories through small things.

A comb made of bone reminds us that, contrary to popular imagination, Vikings were relatively well-groomed; in fact, we know from letters after the Lindisfarne raid that English men had previously begun styling their hair and beards in imitation of the more “fashionable” Scandinavians. A later chronicler complained that the “frivolous whims” of Viking men—combing their hair every day, changing into clean clothes, and bathing at least once a week—made English women prefer them to their husbands.

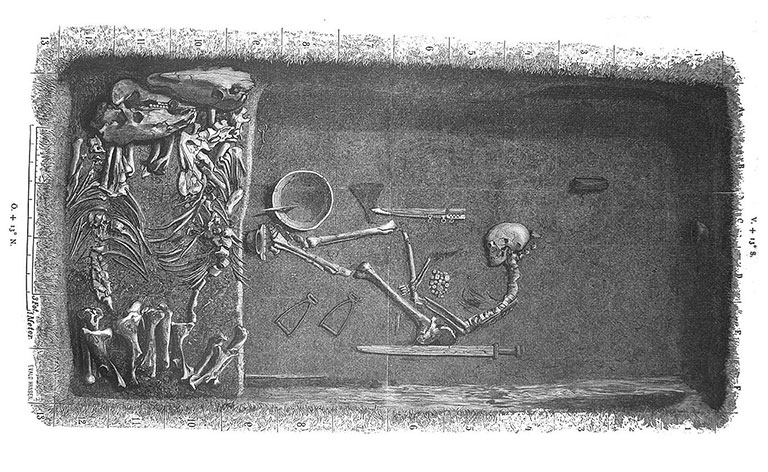

Of course, the exhibition features swords and battle axes—the pointy-end of Viking expansion—but we’d be wrong to assume they were all wielded by men. Remains found in a burial at Birka, Sweden—with sword, shield, battle ax, lances, and arrows designed to pierce chainmail armor—were long held as an example of the quintessential Viking male until 2017, when DNA analysis revealed the person to be biologically female. Archaeologists have also found the reverse: biologically male Viking people buried in traditionally feminine garb.

“Patriarchy was a norm of Viking society, but one that was subverted at every turn,” writes Neil Price in his 2020 book, Children of Ash and Elm. According to Price, who was one of the lead researchers on that Birka grave, Viking-age reality embraced “a true fluidity of gender.” They were, he writes, “certainly familiar with what would today be called queer identities.”

We now know that women, likely serving various roles, made up at least 20 percent of some of the great Viking armies. They also were on the voyages through the North Atlantic and among the traders going East.

Making Their Mark

A small set of scales and weights in the exhibition bear testament to the centrality of trade and to the breadth of Viking travel. Whether it was a chalice plundered from Ireland or a bag of coins obtained selling furs in Constantinople, the Vikings shrewdly determined the value by weight in silver. Silver arm bands and neck rings show they literally wore their wealth. And silver coins from the Abbasid Caliphate in Baghdad attest that Vikings deftly navigated disparate cultures—and sometimes did ride camels.

Viking armies also were multiethnic. As Cat Jarman puts it in her 2021 book, River Kings, genetic and archaeological evidence suggests “Viking groups were composite forces under joint leadership that could pick up and lose members along the way.” One of the two women interred in a lavish ship burial near Oseberg, Sweden, around the year 834 had very close family descended from the Middle East, which Price has noted is “an important reminder that—to put it mildly—not everyone in the North was blond-haired and blue-eyed.”

“There are some really amazing and interesting things about the Vikings that people may not know.”

– Jason Brown, Henry Buhl, Jr., Director of the Science Center and Vice President of Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh

Included in the VIKINGS exhibition, a replica of one of the Viking ships excavated at Gokstad reminds us, in Brown’s words, that “Vikings were the STEM practitioners of a thousand years ago. They developed and used tech that was unprecedented,” including social networks.

Visitors to VIKINGS: Warriors of the North Sea can get a taste for Viking life by trying on replica clothes, hefting a reproduction Viking sword, and coordinating —by means of an interactive computer program—the resources needed to build and outfit a Viking ship.

It’s estimated that a single sail for a medium-sized warship could have required wool from about 136 sheep, as well as three or four people working an entire year to weave it into cloth. Consider the sheep and weaving hours required to outfit a fleet of ships, like the 120 that besieged Paris in 845, and you’re quickly managing flocks in the tens of thousands. And that doesn’t include the spare sail or any clothing and gear for the ship’s crew. You’d also need purse-busting amounts of wood, iron rivets, and tar.

The economics of it all increasingly led to consolidation of power and the eventual creation of the modern states of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden.

Perhaps the most impressive item in the exhibition, standing more than 9-feet-high, is a replica of the Jelling runestone, erected around 965 by Harald Bluetooth, who claims to have “won for himself all of Denmark and Norway and made the Danes Christian.”

“In a way, the Jelling stone marks the beginning of the end of the Viking era,” says Peter Pentz, curator at the National Museum of Denmark, which produced the exhibition. “Unlike almost all other runestones, the text lines are arranged horizontally, as in a book. The stone has been labeled ‘a book in stone’—the runic text and the illustrations form a symbiosis, resembling contemporary European manuscripts.”

Pentz adds that, “In his efforts to establish a modern state for the Vikings, Harald still had to uphold his own and his followers’ ancestral links.” The stone is a form of Viking monument using traditional runic script and language, but “modernized” with a design that also pays homage to the Latin letters and parchment of the sacred books of Europe.

Eventually, Vikings and their descendants became “the establishment.” They were the “Varangian Guard,” the personal protection detail for the Byzantine emperor. In Iceland, they created Europe’s first parliament, and—in a final bit of irony—nearly 300 years after Lindisfarne they ruled as kings of England.

Brown says he hopes visitors to the exhibition will come away with “a more broad and less stereotypical view of Vikings. I really think visitors will be amazed.”

This exhibition has been produced in partnership by The National Museum of Denmark, MuseumsPartner in Austria, and Pointe-à-Callière, Montréal Archaeology and History Complex of Québec, with the collaboration of Ubisoft Montréal.

Receive more stories in your email

Sign upTags:

Science & Nature