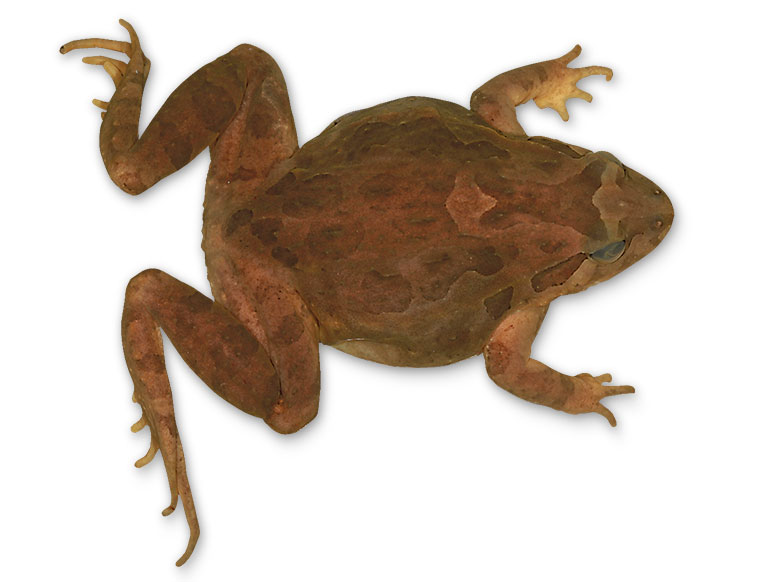

Spanish painted frog (Discoglossus jeanneae), collected in 1971 in Cádiz, Spain

Asian vine snake (Ahaetulla prasina praeocularis), collected in 1913 in Mindanao, Philippines

Pascagoula map turtle (Graptemys gibbonsi), collected in 1978 in Mississippi, U.S.

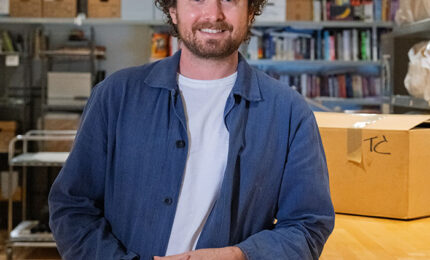

In the world of science, a holotype is a name-bearing specimen that forever defines a species and to which all future finds must be compared. A case in point: Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s Tyrannosaurus rex is arguably its most famous holotype. To discover and name a holotype, scientists must provide evidence—from DNA, morphology (the form and structure of animals), and geographic range, for example—to verify it. Then the findings must be published in a peer-reviewed journal. From start to finish, it’s a process that can take months or years. “It’s intentionally rigorous, slow, and often filled with debate,” says Stevie Kennedy-Gold, collection manager for the museum’s section of herpetology, which studies amphibians and reptiles.

The section of herpetology boasts an impressive 157 holotypes in its collection of more than 230,000 salamanders, frogs, snakes, turtles, lizards, and caecilians (a lesser-known type of limbless amphibian) from 160 countries—95 percent of which are fluid-preserved in a collection facility known as the Alcohol House. And as part of recent upgrades, Kennedy-Gold notes, staff digitized all of the collection’s holotypes, and will soon make images of them available to researchers through a public database dubbed iDigBio—a big deal, since holotypes are so valuable that they’re rarely sent out on loan. n