A black-and-white print of a wide-eyed cat pawing at the air hangs just a few feet above the floor. On closer inspection, the cat is stabbing a dove, not with a claw but a long, curving knife. Nearby, far above eye level, hangs a painting of two faces, one turning to the other, perhaps to whisper a secret. Or, are the faces clouds from atomic bombs? The cross-hatches in the sky could be stars or airplanes on a bombing mission.

Enrico Baj, The Curious Couple, 1956, Charles J. Rosenbloom Purchase Fund

The works in one of Carnegie Museum of Art’s recently reimagined postwar and contemporary art galleries are hung seemingly erratically. They splash with vibrant color, radiate with expressive brushstrokes, and depict figures rendered in a childlike manner. Their creators were part of a resolutely independent European artist group founded in Paris and known as CoBrA, a name that combines the first letters of the founders’ home cities of Copenhagen, Brussels, and Amsterdam. Active from 1948 to 1951, the loose-knit group of poets and painters was united by their experience living under Nazi occupation and driven by a desire to reinvent art, free of all trappings of the past.

“Call of the Wild,” the title given to the CoBrA gallery as part of the exhibition Crossroads: Carnegie Museum of Art’s Collection, 1945 to Now, mirrors the way the CoBrA artists hung their own work—in a nonhierarchical, open-grid system based on the ideas of Dutch artist and designer Piet Mondrian.

“They collectively believed that the trauma of World War II required a complete reconstitution of what art and creativity could be,” says Eric Crosby, the museum’s Richard Armstrong Senior Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art, The Henry J. Heinz II Acting Co-director, and organizer of Crossroads. To achieve this, the artists looked away from the art centers of Paris and New York. To forge their spontaneous, exuberant style of painting, they studied the art of children, people with mental illness, and untrained outsiders.

“The CoBrA group was creating images that are dreamlike, mythical, and tap into primal fears. Their work is psychologically legible.” – Eric Crosby, the Richard Armstrong Senior Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art

While they were interested in the work of surrealist painters like Paul Klee, they wanted to dispense with the movement’s emphasis on dreams and make art that emulated real life. As Danish painter and CoBrA founding member Asger Jorn wrote, “Beautiful, ugly, impressive, disgusting, meaningless, grim, contradictory, etc. … It makes no difference, as long as [art] is life, vigorously pouring forth.”

The artists had an affinity for animals—particularly the cobra—and painted from instinct. In the words of Dutch artist Constant Nieuwenhuys, “A painting is not a structure of colors and lines, but an animal, a night, a cry, a man, or all of these together.”

On often shockingly colorful canvases, figures emerge from expressive fields of gestural abstraction. While at first glance the paintings seem playful, a darkness lurks below. “If you look casually, the figure seems like a naïve scrawl of a child with a baseball cap,” Crosby describes Nein (No), a work by Dutch poet Lucebert that portrays a figure in profile. “Look closer, and you see this is a traumatized body. The picture has an X-ray quality. Am I looking at the surface of a body or into a body?” A speech bubble floating on the black canvas declares “Nein,” a defiant act of refusal.

Lucebert, Nein, 1964, Gift of James L. Winokur

A one-man Carnegie International

Belgian artist Pierre Alechinsky was just 22 when he joined the short-lived but influential movement. The son of a Jewish doctor who fled violent anti-Jew riots in Russia, he was shattered by his experience living through the bombing raids of occupied Brussels. “We bent down, picking up bits and pieces of the dead,” he told Harry Schwalb of the Pittsburgher in 1977. Through CoBrA, he was able to embrace joy and freedom, without denying the trauma of the past. Critic Jacques Putnam wrote that CoBrA gave Alechinsky “a lesson in freedom … the thirst for work which approaches pleasure, an inspiration, and aspiration.” Drawing on Japanese calligraphy, Alechinsky created a unique style of sweeping, sinuous lines scrawled on large sheets of paper, which he then affixed to canvas for display. He worked on the floor, crouching in a posture that imitated his description of searching for the dead.

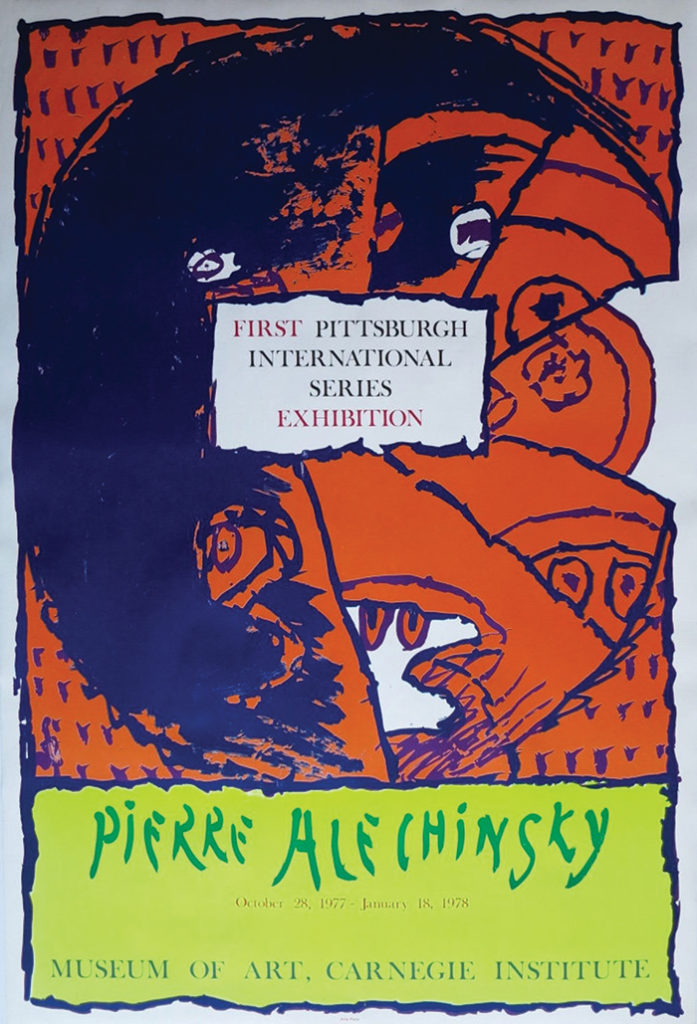

Alechinsky was introduced to audiences in Pittsburgh in 1952 when one of his paintings was included in the Carnegie International. He went on to be represented in each subsequent International, known then under a variety of names, until 1977. That year, then-museum director Leon Arkus experimented with a new format for the landmark exhibition: a single-artist show featuring none other than Alechinsky. In addition to awarding Alechinsky the lucrative Andrew W. Mellon Prize, Arkus filled the Scaife Galleries with the artist’s monumental canvases, many of which were black-and-white images portioned off into squares like comic strips. It served as a retrospective for Alechinsky and marked the largest exhibition of his work in the U.S. at the time. While the response to the single-artist format was mixed, the Pittsburgher gave Alechinsky’s canvases a rave review. Schwalb remarked, “His works fairly crackle with electricity; some surge with such vehemently restless life, you almost feel a draft as you walk by.”

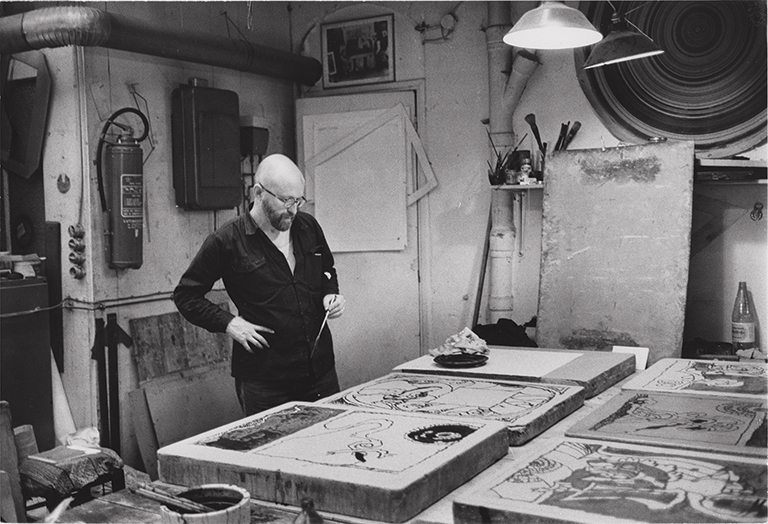

Pierre Alechinsky at work in 1974. The photo was taken by John Lefebre, who gifted it to the museum.

The museum abandoned the International’s new format after just two iterations, when Jack Lane succeeded Arkus as museum director. But not before acquiring, under Arkus’ leadership, one of the world’s largest holdings of CoBrA artworks, numbering nearly 400 objects, including paintings, prints, drawings, and sculpture. One hundred and seventeen are by Alechinsky, who gifted 89 to the museum, placing him among the museum’s 25 most-collected artists.

“As I was going through our storage, I kept encountering quirky, funky mid-century abstraction from Northern Europe. I felt this untapped aspect of the collection really deserves to see the light of day.” – Eric Crosby

“With his collection strategy, Arkus broadened the story of art by looking to other global art centers besides New York and Paris,” says Crosby. In addition to adding CoBrA artists to the museum’s collection, Arkus encouraged private collectors in Pittsburgh to purchase their work. “As I was going through our storage, I kept encountering quirky, funky mid-century abstraction from Northern Europe. I felt this untapped aspect of the collection really deserves to see the light of day.”

Over time, the CoBrA group somewhat faded from art’s historical view, eclipsed by the narrative of abstract expressionism with its heroic painters committed to pure abstraction and centered in New York. While artists such as Jackson Pollock were using abstraction to give form to their inner subjectivity, CoBrA members were interested in forming a collective response to the shock of war, political oppression, and social upheaval. They remained committed to the figure—figures that were strange, disarticulated, or a hybrid of animal and human. “The CoBrA group was creating images that are dreamlike, mythical, and tap into primal fears,” Crosby says. “Their work is psychologically legible.”

Pierre Alechinsky, Luxe, Calme et Volupte (Luxury, Calm, and Pleasure), 1969, Gift of the Women’s Committee © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Crosby went into his curating process without preconceived ideas. “I wanted to listen to the collection and see what new stories it could tell,” he explains. As a result, he included work by CoBrA founding members such as Constant and Jorn but also lesser-known artists such as Enrico Baj and Raoul Ubac. He includes Alechinsky’s 1969 Luxe, Calme et Volupte (Luxury, Calm, and Pleasure), a riff on Henri Matisse’s many paintings of bathers but one in which the figures are deconstructed into swirling, tentacle-like shapes, tangled up in each other as the dark sky presses downward. The influence of calligraphy is apparent in the sinuous strokes on the nearly 10-foot-long canvas. (Many of Alechinsky’s works in the collection are this size or larger, making them challenging to display.) “I love this one because it’s the most colorful,” Crosby says. “I’m interested in how he takes that classical motif of bathers and reconfigures it with the CoBrA language of very vigorous and violent brush work.”

A poster advertising Pierre Alechinsky’s solo exhibition in 1977.

Electric brushstrokes

Alechinsky’s dynamic brush work caught the eye of a young Keith Haring. Born in 1958 in Reading, Pennsylvania, Haring rose to prominence in the 1980s because of his drawings on New York City subways. His iconic style consists of figures outlined in black and animated by haloes of kinetic lines.

In 1977, Haring was living in Pittsburgh after having dropped out of the city’s Ivy School of Professional Art. While preparing for a solo show at the Pittsburgh Arts and Crafts Center, now Pittsburgh Center for the Arts, he repeatedly visited Carnegie Museum of Art to study Alechinsky’s work.

“It was the closest thing I had ever seen to what I was doing,” Haring said in an interview published after his death in a 2015 catalog of his work. “There were frames that went back to cartooning—to the whole sequence of cartoons, but done in a totally free and expressive way, which was totally about chance, totally about intuition, totally about spontaneity—and letting the drips in and showing the brush—but big!” Haring watched the film included in the exhibition that showed Alechinsky working on a large piece of paper spread out on the floor. This inspired Haring to start working on a similar scale using loose, expressive brushstrokes.

The current installation mirrors the way CoBrA artists hung their own work—in a nonhierarchical, open-grid system based on the ideas of Dutch artist Piet Mondrian. Photo: Bryan Cohen

In a neighboring gallery, within eyeshot of Alechinsky’s vibrant Luxe, Calm et Volupte (Luxury, Calm, and Pleasure), hangs an untitled work by Haring from 1981. In this 12-foot-high, bright yellow canvas, Haring’s thick black lines echo Alechinsky’s serpentine curves. This is entirely by accident. Crosby only learned about the artists’ relationship after installing the gallery while socializing with an art historian—the kind of chance discovery that would have delighted the CoBrA artists.

“I hope [visitors] see something strange that encourages them to look closer and reflect on the relationship between painters and the political and social backdrop of their work.” – Eric Crosby

In addition to their influence on contemporary painters like Haring, Crosby finds continued relevance in CoBrA’s approach positing artists as “reactive agents responding to their world, the events of the day, the social, political, and cultural currents of the moment.” In recent years, there has been a resurgence of interest in CoBrA, with major exhibitions at Nova Southeastern University Art Museum in Fort Lauderdale (to which Carnegie Museum of Art loaned four works) and Blum & Poe in New York in 2014 and 2015, respectively; a 2018 sale by the auction house Christie’s; and a 2017 scholarly assessment by independent curator Alison M. Gingeras titled The Avant-garde Won’t Give Up: Cobra and Its Legacy.

In resurfacing 26 CoBrA works, Crosby brings salience to politically engaged artists while revealing a story that for many years lay dormant in museum storage. “I hope visitors are compelled by the color and vigor of these paintings,” he says.

“I hope they see something strange that encourages them to look closer and reflect on the relationship between painters and the political and social backdrop of their work. I also hope they come away with a sense of the idiosyncrasy and depth of the museum’s holdings. The CoBrA collection is something quite unique, and you can only experience it at the Carnegie.”

Receive more stories in your email

Sign upTags:

Art