More than 20 years ago, Carnegie Museum of Art acquired a vast record of African American life in Pittsburgh during the 20th century. It’s a treasure trove of 70,000 print images, photo negatives, and videos from the iconic Charles “Teenie” Harris, longtime photographer for The Pittsburgh Courier, one of the nation’s most prominent Black newspapers, spanning the late ’30s into the 1970s.

As the museum worked to preserve and digitize the photos and identify the people portrayed in them, it organized temporary exhibitions of the collection in which viewers were treated to several dozen images at a time—of dance halls and baseball games, intimate family moments and Civil Rights protests. Often, in a single frame and unfiltered, Harris presented the seldom-seen complexity and joy of African American life and identity.

Each exhibition provided snippets of what is considered one of the country’s most detailed and comprehensive photographic records of the Black urban experience. But there has never been a space that showcased all the facets of the archive at once, as Harris had always hoped.

“Harris wanted you to see it all, but he also wanted you to listen to the stories he was presenting in his art,” says Charlene Foggie-Barnett, Charles “Teenie” Harris community archivist. With every image, she adds, “He is leaving clues. He is revealing story lines and truths. He’s making a statement.”

Later this year, museumgoers for the first time will be able to explore this vast archive with a reinstallation of Harris’ work in the Scaife Galleries. The new Charles “Teenie” Harris Archive Gallery will feature never-before-seen components of the archive, including reels of film in canisters, and prints, some in color. Visitors will even be able to view Harris’ photographic negatives, which make up the bulk of the collection.

“We’re taking a more comprehensive, intentional, and creative approach to sharing and honoring the Teenie Harris Archive and how the photographer’s art has illuminated the city’s history,” says Dana Bishop-Root, the museum’s director of education and public programs, who worked with Foggie-Barnett and Curator of Photography Dan Leers, as well as a team of creatives, on the project. Throughout their work, which is ongoing, they considered how the museum invites, welcomes, and engages with the community—including those who knew Harris, his subjects and their families, schoolchildren, teachers, scholars, and other visitors from near and far.

“Thinking about the ways that people can experience the archive has been at the forefront of our approach to sharing it,” says Bishop-Root. “We’ve long said that people need the museum, but the museum needs people to keep it alive, inclusive, vibrant, and contemporary.”

Viewing ‘Teenie’ as Never Before

When the exhibition opens, Harris’ films, works in color, self-portraits, negatives, and more will be available for visitors to work with, listen to, read about, see—and yes, touch—Leers says.

For the first time, visitors will view Harris’ videos and still images side by side, projected on a wall using a multichannel projector. Visitors can also interact with Harris’ negatives, the thin strips of transparent plastic film that gave the photographer his first look at the subjects, using a light table stationed in the gallery. This opportunity to touch and explore the negatives is possible only because of the decades of intensive work that has gone into preserving the archive.

Many of Harris’ negatives were stored in his basement studio before the museum received them. “There were a group of negatives that were seriously curled up on each other and without protective sleeves,” adds Leers. The work of restoring and digitizing them, which is nearly complete, has been intensive and daily over the past two decades.

Pittsburghers first saw Harris’ photos in black and white in the pages of The Pittsburgh Courier, the city’s influential Black newspaper. For the first time, the museum will print some of those images on newsprint, giving visitors a look and feel for how Harris’ photographs appeared when they rolled off the press.

Experiencing the Charles “Teenie” Harris Archive Gallery will also include seeing the photographer as never before.

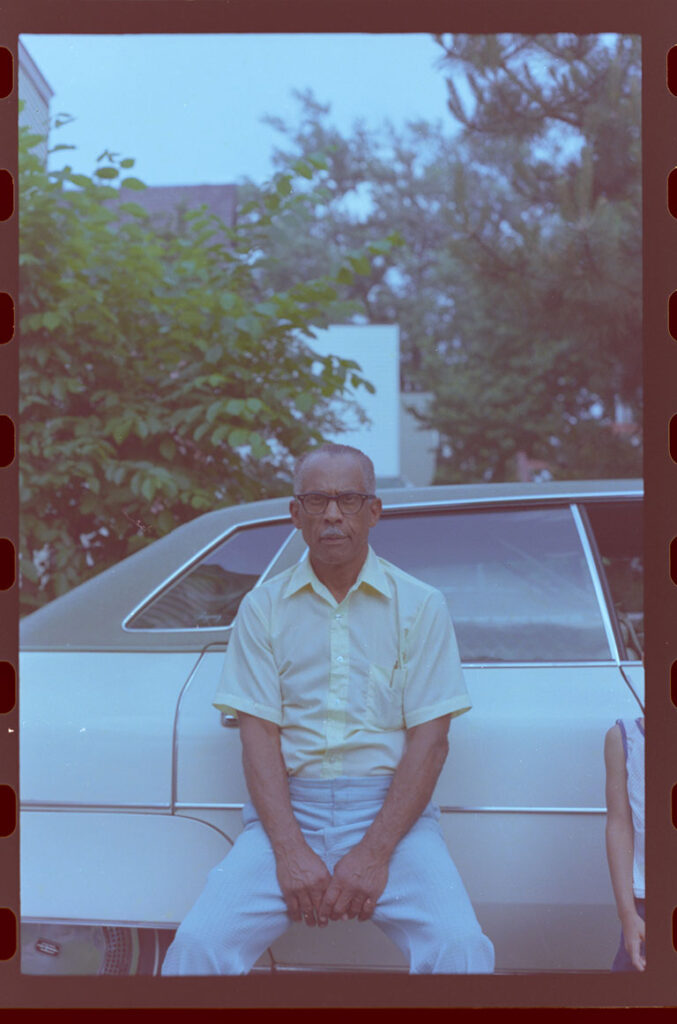

Harris was a month shy of his 90th birthday when he died on June 12, 1998. But in exhibitions of his work, the artist is typically portrayed as a much younger man in his 30s—bright-eyed, with finger waves in his black hair, and sporting his signature suit and tie. For the first time, the museum will present self-portraits, some in color, of Harris as an older man.

“Deciding to present portraits of the older Harris offered an opportunity for us to broaden the personal image of Harris, and who he was as a community member, family man, and artist,” says Leers. Those new portraits of the photographer will be interspersed in a mosaic display that features Harris’ life and career, layered with the major moments in Black history, American history, and international history he chronicled.

The museum also wants to broaden and focus on the visitors who will be engaging with the work Harris created.

“Deciding to present portraits of the older Harris offered an opportunity for us to broaden the personal image of Harris, and who he was as a community member, family man, and artist.”

–Dan Leers, Curator of Photography, Carnegie Museum of Art

Visitors to the gallery will step into an expansive space that is accessible to people of different abilities, and designed for sitting, listening, viewing, touching, reading, learning, talking, and lingering as “they experience the depth of Teenie Harris’ work and how he was looking at the world,” explains Bishop-Root.

For example, the museum is outfitting the gallery space with modular seating that can easily move and be rearranged when groups and individuals come to watch a film, hear a lecture, or just talk to each other about Harris’ art. When Foggie-Barnett considers this intentional gathering space, she sees opportunities for critical conversations to also happen there: “about race, reconciling, identity, and the unknown of Black life in America,” issues she says Harris confronted in his images without saying a word.

Seeing Themselves in the Images

As a community archivist and longtime Hill District resident, Foggie-Barnett understands the importance of forging and cultivating relationships with surrounding communities, especially with those who call the Hill District home. Much of her work has focused on identifying individuals in Harris’ images and, whenever possible, meeting with those who are still living to collect their oral histories.

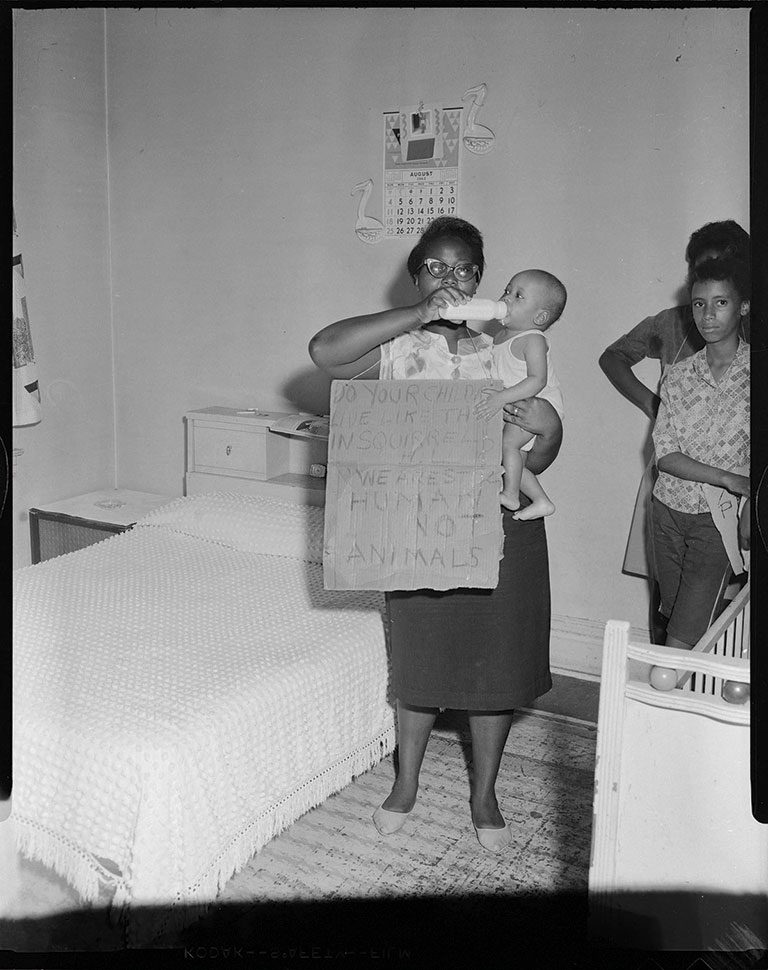

It’s necessary, rewarding, and ongoing work that has been “fundamental to expose the archives in ways that are personal,” says Foggie-Barnett, and that engender trust from those who share their memories and stories with the museum. One such relationship, she recalls, was with Daisy Curry Simmons, who was a young wife and mother of six when Harris photographed her on August 17, 1963. On that day, in her small, tidy bedroom, she stood in silent protest, wearing a hastily written cardboard sign on a string around her neck. It read: “Do your children live like this in Squirrel Hill? We are still human not animals.” Inside the museum, 58 years later, Curry Simmons stared for the first time at that photo of her younger self hanging in the Harris gallery.

In March 2024, Curry Simmons’ daughter called to inform Foggie-Barnett, who had collected Curry Simmons’ oral history, that her mother had passed away. That phone call, says Foggie-Barnett, represents the kind of cyclical relationship the museum wants to have with people whose lives have been touched by Harris’ work.

“They embrace us if we embrace them,” Foggie-Barnett says.

Carnegie Museum of Art plans to engage a lay volunteer corps over the next two years to help gather oral histories and memories from people who can speak about Harris and the lives reflected in his work. Those histories will help shape how the Harris Archive is maintained, Bishop-Root says.

“Having citizen archivists who will get to experience the Harris Archive in this way is what excites me,” says Bishop-Root, who is eager to incorporate these volunteer efforts into the museum’s programming. She also sees it as a “formalized way we can ask those in the community to contribute to the knowledge and context we are building around the Teenie Harris photographs.

Photo: Joshua Franzos

Photo: Joshua FranzosDaisy Curry Simmons views the image of herself that Charles “Teenie” Harris

photographed in 1963.

“I hope that they will see themselves as adding value, in their own way.”

Foggie-Barnett shares that vision of citizens as vital to helping keep the Harris Archive alive and relevant. “We are creating an opportunity for everyday citizens to become archivists who can inform the museum and then share what they are finding and learning with the world, and with family and friends.”

Indeed, Foggie-Barnett is part of the community that Harris captured.

On the walls of her Pittsburgh home, and included in some Harris exhibitions, are photos of her as a young girl. She had her first photo shoot with Harris when she turned 1 year old. Harris photographed the smiling Foggie-Barnett sitting on a table next to her big birthday cake. It’s one of more than 300 images Harris took of her family. She is now a well-respected “steward” of the Teenie Harris Archive, involved in preserving, curating, and broadening the collection’s reach and community relevance.

Those deep roots and her memories of Harris have proven invaluable to preserving and interpreting this archive, says Leers.

“Our collaboration has been incredible; especially given Charlene’s relationship to Harris and the stories she’s collected. She has shaped how I look at the different kinds of experiences and views that everyone brings, and that are unique to this reinstallation process.

“I used to look at the [Harris] Archive as a record of the past,” he adds. “But now I see that it is living.”

Leadership support is provided by the Drue and H. J. Heinz II Charitable Trust. Major support is provided by the Henry Luce Foundation.

Support the Charles “Teenie” Harris Archive!

Find more information at www.carnegieart.org

Receive more stories in your email

Sign up