It all started in Thailand in 2005, when Zeb Hogan came face-to-face with a catfish the size of a grizzly bear.

“I’d been around a lot of big fish at that point, but that was the biggest one I’d ever seen,” says Hogan, a fish biologist at the University of Nevada, Reno.

The species is known as the Mekong giant catfish, a silvery-gray behemoth native to Southeast Asia where it hangs out on the rivers’ bottom and gnaws algae off boulders. While local fishermen had seen these creatures before, at 646 pounds and nearly 9 feet in length, this specimen was by the far the most impressive anyone could remember. Curious if it might be the heaviest freshwater fish on Earth, Hogan started digging through catch records in Thailand, which dated back to 1981, and found nothing that surpassed the heavyweight.

“I still haven’t found anything bigger,” he says.

Fish biologist Zeb Hogan with a catfish that weighs more than 100 pounds in the Salween River Basin in Malaysia, where he was filming his Nat Geo Wild TV series, “Monster Fish.” Photo courtesy of Zeb Hogan, University of Nevada, Reno

Since then, Hogan has spent the past two decades studying freshwater giants around the world. On his Nat Geo Wild TV series “Monster Fish,” audiences watch in awe as their host tracks down and catches everything from electric eels to living-room-sized stingrays. And soon, Carnegie Museum of Natural History visitors will be able to walk a mile in Hogan’s waders thanks to the immersive exhibition Monster Fish: In Search of the Last River Giants, opening Oct. 8.

Hogan calls the experience a “one-stop shop for learning about these big fish,” many of which are quietly dwindling from dozens of locations around the world. In 2019, Hogan published a study in Global Change Biology that found freshwater megafauna populations plummeted by 88% from 1970 to 2012. “This is a group of animals that people don’t know very much about,” says Hogan. “They’re not featured in most aquariums. They’re not featured a lot on TV. And they’re not easy to go out and see yourself.”

But they’re worth getting to know, he says, and lots of them need our help if they’re going to survive for future generations to understand and enjoy. What’s more, big fish are indicators of ecosystem health, and the fact that so many populations are diminishing should serve as a wake-up call.

Wonders of the World

When people think of giant aquatic creatures, they tend to picture ocean dwellers, such as whales, sharks, sea turtles, and squid. But the world’s rivers and lakes are home to nearly half of all the fish species on Earth—and some of them can be truly massive.

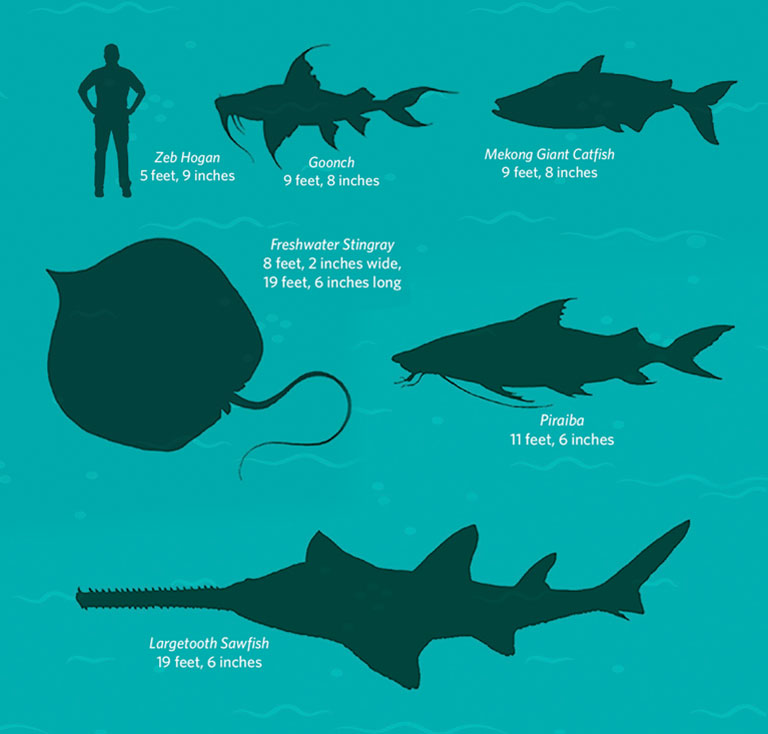

Take the largetooth sawfish of Australia, a shark relative that boasts a long nose studded with teeth—a living chainsaw. At up to 20 feet in length, this species can grow as long as a giraffe is tall.

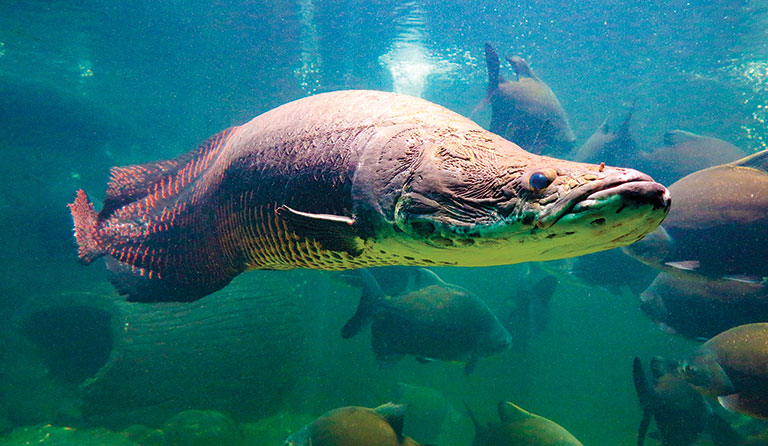

In the Amazon river system, there’s a colossus known as the arapaima or pirarucu, a brightly colored green and red fish that grows up to 10 feet long and weighs more than a full-grown white-tailed buck.

A pirarucu, which can weigh more than an adult white-tailed buck.

You don’t have to travel to the other side of the world to find giants, though. The alligator gar, a primitive fish related to the bowfin and found in the American Southeast, would be 2.5 feet taller than Shaquille O’Neal if you could somehow stand one up next to the retired basketball star.

The American paddlefish, which can live upwards of 60 years, has a body like a shark and reaches lengths of nearly 5 feet. It was once a common sight from the Mississippi River and Great Lakes all the way up through the Ohio, Monongahela, Allegheny, Clarion, and Kiskiminetas rivers until 1919, when it was last spotted.

In 1991, the Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission began reintroducing some 158,000 American paddlefish fingerlings into state waterways. Unfortunately, they failed to reach maturity in any great numbers, and the program was discontinued in 2011. However, there may still be some 5-footers out there, as a fisherman hauled a sizeable paddlefish out of the Allegheny River in 2017.

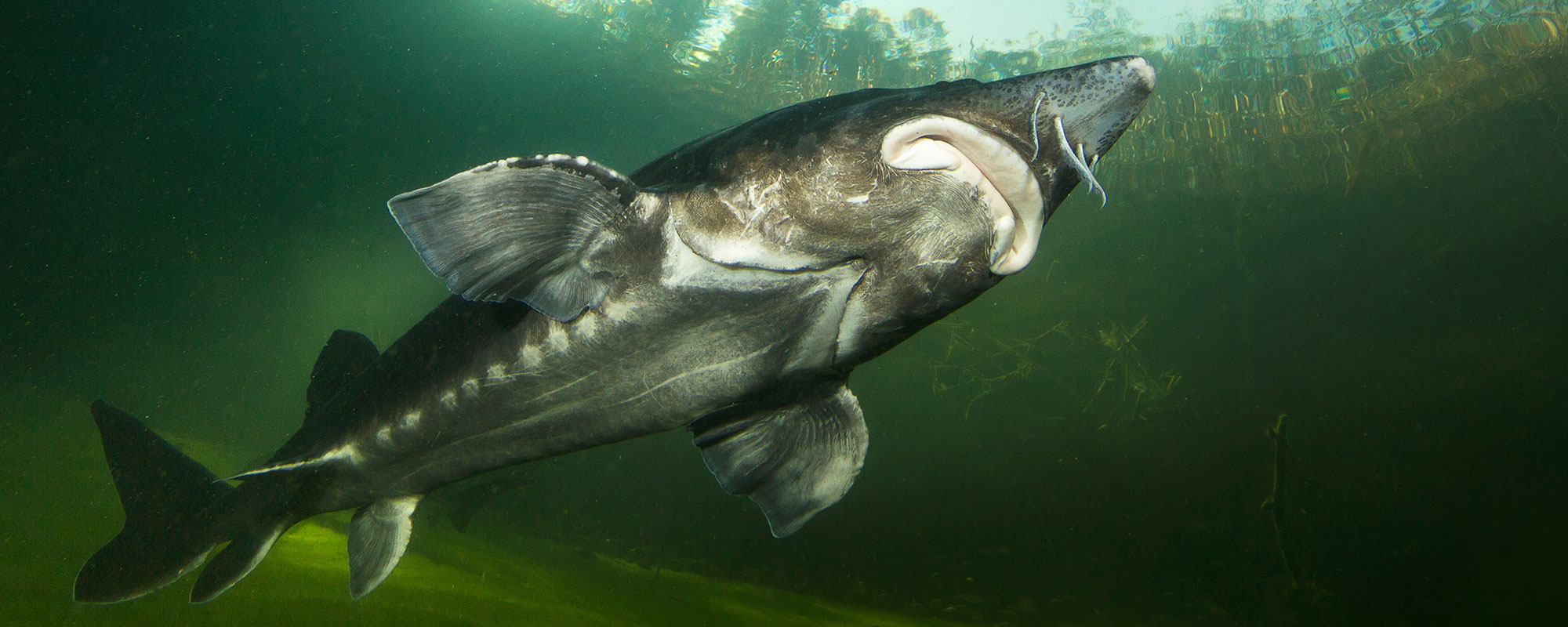

Pictured in the wild an American paddlefish, now a rare sight in Pennsylvania

While Hogan typically takes years to learn about the species he catches and then gets to spend only a few fleeting moments with the animals in person, the Monster Fish exhibition will let visitors bask in their gloriousness en masse. Life-size replicas depict each species at its absolute biggest, says Hogan, so you can size up the giants and truly get a sense of their enormity. There are also interactive displays and games that target different age groups.

One of Hogan’s favorite parts of the exhibition is a giant scale that equates your weight to various kinds of monster fish. You basically get everyone to pile on, he says, and see if you can match the weight of the world’s underwater titans—though you might need 20 adults or more if you’re going to stack up to something like a beluga sturgeon, which tops out at more than 2 tons.

“Every time I see one of these fish, I’m blown away by the size of them,” says Hogan.

Zeb Hogan with a giant freshwater stingray in the Mekong River. Photo courtesy of Zeb Hogan, UNR Global Water Center

Dam It All

While there’s no way not to feel awe when standing next to some of these gargantuan fish, the tragedy is that many species are quickly fading into legend. Consider the Mekong giant catfish that Hogan holds in such high regard.

“There are records of multiple sites along that river catching thousands of these fish in the 1800s,” he says. “And then you see reports of sites catching hundreds of fish in the 1940s, then dozens of fish in the 1990s. And then the last big Mekong giant catfish I’ve seen was in 2015. A single fish. It’s a catastrophic decline.”

So who or what is to blame? While catching too many fish for sport, meat,

or eggs—what scientists call “overharvesting”—has certainly dinged up monster fish populations worldwide, Hogan points to one main culprit: “Dams are what cause extinction,” he says.

“A lot of these fish need to migrate upriver to spawn,” he explains. “So overfishing drives numbers down, but a dam kind of makes survival impossible.”

In fact, Hogan was part of a study published in the journal Nature in 2019 that found only 37% of the world’s largest rivers have yet to be dammed, and most of those occur in just a few remote areas, such as northern Russia.

“This is a group of animals that people don’t know very much about. They’re not featured in most aquariums. They’re not featured a lot on TV. And they’re not easy to go out and see yourself.” – Zeb Hogan

But it’s not all bad news. While many underdeveloped nations are still looking to dams for the electricity and irrigation they can provide, over the past century the United States has removed 1,722 dams. And Pennsylvania leads the charge. In 2019, the Keystone State removed 14 dams, which was more than any other state except California. It was the first year this side of the millennium that Pennsylvania didn’t hold the honor of most dams removed.

Of course, dams are just one threat among many to freshwater fish.

“Before Europeans arrived, two-thirds of Pennsylvania was covered in trees, and there were brook trout swimming in all of our streams,” says Monty Murty, director of the Forbes Trail Chapter of Trout Unlimited. “But by 1900, Pennsylvania had cut down two-thirds of its trees, and brook trout were gone from 90% of their native habitat.”

Trees provide shade that keeps waterways cool, which cold-water fish like brook trout require. At the same time, non-native species like brown and rainbow trout take over these habitats once introduced. And that’s to say nothing of the region’s long-standing troubles with air and water pollution, which have only begun to be addressed in the past 50 years.

Rather than simply lament what was, Murty and his fellow members of Trout Unlimited perform habitat restoration, such as planting trees and protecting those that are already there from invasive scourges, like the hemlock woolly adelgid that feeds by sucking sap from hemlock and spruce trees. The organization also seeks to educate the public about the ongoing threat of climate change through participation in Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s Climate and Rural Systems Partnership, which brings together a diverse network of people such as outdoor recreationists, educators, and scientists.

A life-size sculpture of a goonch on view in the exhibition. Photo: Rebecca Hale

“I’ve studied these fish my whole life, and I know that their situation is not good. But [the exhibition] IS set up for you to appreciate that these things are out there, that they’re extraordinary, and they need our help.” – Zeb Hogan

In 2011, Jennifer Sheridan, a tropical conservation biologist and the museum’s assistant curator of amphibians and reptiles, scoured every scientific study she could get her hands on that measured how shifting climate can affect body size. She confirmed a worrying trend—in most cases, animals grow smaller as the temperature rises. And that’s across the board, from scallops and oysters to salamanders, toads, gulls, sheep, and deer.

Worst of all, the effects of climate on size do not appear to happen to every creature at the same rate.

“If everything were getting smaller, then you would kind of just have this nice, miniaturized ecosystem,” says Sheridan, who is working on an update to the 2011 study. “But because some things get smaller and others don’t, you tend to get this mismatch.”

So some species win while others lose, Sheridan explains, and those effects can upend relationships between pollinators and their plants or predators and prey that have been millions of years in the making. And for big fish, those size changes may well be compounded by everything else that they have to deal with.

“There’s Still Hope”

Even with the writing squarely on the wall for many superlative fish species, Hogan says he sees the Monster Fish exhibition as a source of inspiration, not a eulogy.

“I’ve studied these fish my whole life, and I know that their situation is not good,” he says. “But it’s set up for you to appreciate that these things are out there, that they’re extraordinary, and they need our help.”

Hogan points to the 240-pound sturgeon caught in Michigan earlier this year as proof that “a lot of positive things are happening.” Not only is the fish one of the largest recorded in the United States, but it’s also believed to have hatched sometime in the 1920s. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, which hauled in the beast, implanted a scannable tag and then released it back into the Detroit River.

Also of note, Hogan says many sport anglers now are of the mindset that catching and releasing is better than catching and keeping. And with dams coming down and rivers becoming healthier and free of pollution, there’s a lot to get excited about.

In Pittsburgh, you can see those changes bearing fruit, as fish-predators like river otters and bald eagles have returned to the area after decades of absence. The very fact that they are back, and thriving, means there are fish to eat.

“We haven’t turned the tide everywhere, but it’s obviously what we want,” says Hogan. “I really do think we can save most of these fish from extinction. Until a species is extinct, there’s still hope.”

Monster Fish: In Search of the Last River Giants is sponsored by Highmark Blue Cross Blue Shield, Pennsylvania Virtual Charter School, and Dollar Bank.

Receive more stories in your email

Sign upTags:

Science & Nature