It’s a toss-up for favorite moment of the morning for 14-year-old Jacob Schmitt: lying on the floor with Andy Warhol’s “floating balloons” dancing overhead, or mashing together blood-red lips and a pastel-colored cat in a collage he crafted in the underground studio of Andy’s museum, The Factory.

“I feel like myself when I do art,” says Jacob.

For Jacob’s mom, Jane Stadnik, it’s about something just as powerful: spending two enjoyable hours in a museum with her son. Jacob has autism, and outings to busy public places can be overwhelming for him and those around him. But on this particular Saturday morning at The Andy Warhol Museum, the goal is making teens and young adults like Jacob with sensory sensitivities—and their caregivers—feel welcome.

“When you come to a program like this, where people are knowledgeable about autism, if he’s stimming [self-stimulating behavior], it’s not a big deal. People go on their way and it makes it so much more of a relaxed experience,” says Stadnik, who made the trip from Ambridge after learning about the free program on Facebook.

“Art has been really inclusive for Jacob. In math class, he notices that he’s different from other kids. But when he rolls into art class, he’s like everyone else. It’s the same here. Art is an equalizer.”

This morning’s sensory-friendly program is not unlike most of the museum’s tours that introduce visitors to Warhol’s life, art, and practice. It reveals many artifacts from the Pop artist’s storied life—from his working-class Pittsburgh roots to his New York stardom. It also points to the lasting impact Warhol still has on artists working today, including the global sensation Chinese activist-artist Ai Weiwei. There’s even dedicated time for artmaking, including Warhol’s signature process of silkscreening.

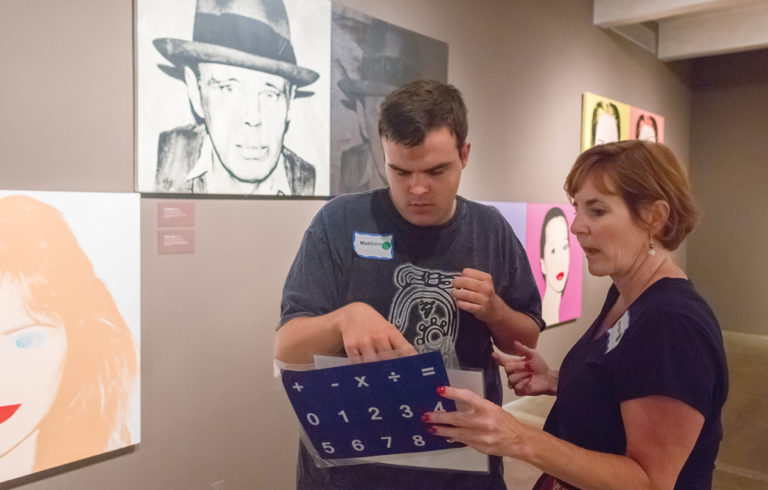

Jacob Schmitt and his mom, Jane Stadnik (at right), participate in an ice breaker that prompts the group to practice facial recognition skills.

“Art has been really inclusive for Jacob. In math class, he notices that he’s different from other kids. But when he rolls into art class, he’s like everyone else. It’s the same here. Art is an equalizer.”

– Parent Jane Stadnik

What is a little different with this tour is the preparation. Knowing that many in today’s group are sensitive to loud noises, bright lights, and crowds, in advance of the visit staff made available a “pre-story” video, designed to inform participants about what they could expect to find at the museum—from the sights and sounds of specific galleries to the location of the bathrooms.

On each floor of the museum is a quiet area that includes a bench and a box full of calming aids that participants grab as needed: noise-cancelling headphones and sunglasses as well as super-stretchy fidgets and weighted blankets—self-regulating tools that promote focus and concentration, decrease stress, and keep fidgeting fingers busy.

Also on hand for support and conversation: a small team of occupational therapy students from the University of Pittsburgh and Chatham University.

“It’s not about changing the experience of being at the museum or how Warhol’s art is viewed,” says Leah Morelli, The Warhol’s school programs coordinator who developed the pilot program in partnership with a focus group and advisory committee. “It’s about providing multiple pathways for discovery and a successful experience.”

The art of reading a face

On the museum’s sixth floor, artist-educator Christen DiLeonardo pauses in front of a series of blue, gold, and grey silkscreens of Jackie Kennedy. The paintings, she explains to a wandering group in tow, are significant because they combine two of Warhol’s signature themes—celebrity and fatal disaster.

Fascinated by the relentless media coverage of President John F. Kennedy’s assassination in 1963, Warhol zeroed in on the First Lady, culling from newspapers and Life magazine eight images that, when cropped, juxtapose her facial expressions immediately before and after her husband’s murder to powerful effect.

“Here Warhol gives us a rounded view of Jackie at her most raw,” DiLeonardo says. “In which images does she look happy?”

Pointing to a canvas featuring the First Lady beaming in a pillbox hat she wore on that fateful November day, Dale Johnston replies, “that one.” “Yes!” DiLeonardo counters. “What tells you that she’s happy?”

“She’s smiling,” asserts Johnston.

“Yes! What is it about her mouth that tells us that?” DiLeonardo asks, this time prompting the larger group. As if on cue, two participants use their fingers to push the corners of their lips toward the sky.

For Johnston, 27, and other adults and children on the autism spectrum, reading facial expressions and nuanced body language is a challenge that art can help them overcome.

Johnston is no stranger to art museums. An especially big fan of Warhol friend and collaborator Keith Haring, Johnston and his mother, Shawn, say they both enjoy art, how it makes them feel, and what it has to teach them.

“It’s amazing how art opens him up,” says Shawn, noting that Dale is also active with Manchester Craftsman’s Guild. “I like to make things with my hands,” adds Dale, a common refrain from the day’s participants, all of whom spent about an hour in the museum’s studio doing any combination of three projects: watercolor, collage, and silkscreening.

In the portrait gallery, participants work in pairs to match the emotions on faces in printed handouts with those in Warhol’s colorful Pop paintings. Above: Parent and advisory committee member Chrisoula Perdziola and her daughter, Eva, participate.

“For me, The Warhol is a place of acceptance for uniqueness and differences of all kinds. We feel relaxed and at home here. That’s big.”

– Chrisoula Perdziola, parent and advisory committee member

“Coming to an art museum, looking at portraits, making portraits, that’s more of an adult way to practice these very important life skills,” says Kelly Ammerman, a teacher at City Connections, Pittsburgh Public Schools’ community-based life skills and independent living program designed for students ages 18 to 21 who have moderate to severe disabilities.

“Programs like this help get these young people out into the community, engaging with people and in topics that interest them,” says Ammerman, who has accompanied both teens and young adults to sensory-friendly events at The Warhol. “It also allows them to get the lay of the land; so, for some, they can feel prepared and comfortable coming back on their own.”

Twenty-year-old Maximus Chaney was so inspired by Ai Weiwei’s artful protest of placing fresh flowers inside the basket of his bicycle each day while banned from leaving China for 600 days, he vowed to build a bicycle out of Legos, a material also used by Ai. “I might even donate it,” he says. “I know one thing for certain. I’d like to come back [to The Warhol] and bring my grandmother.”

In an exercise on the second floor, with Warhol’s colorful Pop portraits as the backdrop, program leader Morelli gives the participants photocopies of faces—some expressing happiness, sadness, even indifference—and sends them off in pairs to match the emotions on the paper to those in Warhol’s paintings.

For ninth-grader Bella, on her first visit to The Warhol from Streetsboro, Ohio, it was a good social exercise. “We knew it would be a great opportunity for a hands-on experience, where Bella could learn and create, and also meet and interact with new people socially, which is always good,” says Bella’s mom, Keri Stoyle, who found the program online while making plans for the pair to come to Pittsburgh to paddleboard and ride bikes. “She’s learning to advocate for herself.”

Like any gathering of teenagers, there was, of course, talk of music. At Jacob’s mention of his love for Green Day, Chrisoula Perdziola, whose teenage daughter, Eva, has autism and is limited verbally, notes that despite the fact that all five of Eva’s senses are heightened, she loves listening to music—Green Day and Foo Fighters, in particular. “And she likes to listen to it loud,” says Perdziola, laughing.

Embracing difference

Perdziola remembers opening day of The Andy Warhol Museum in 1994. She still has a Polaroid of herself walking in the front door. That same day she bought a print of one of Warhol’s most famous paintings, Flowers, in the museum store. Four years later, when they were preparing to have Eva, they put the print in her room, and it’s been there ever since.

“Warhol did a lot of art outside of the box, and kids and adults on the spectrum live outside of the box,” says Perdziola, who works for PA Museums (the state’s museum association), is active in Autism Connection of Pennsylvania, and brings the perspective of a caregiver to The Warhol’s advisory committee for sensory-friendly programming. “For me, The Warhol is a place of acceptance for uniqueness and differences of all kinds. We feel relaxed and at home here. That’s big.”

Having Perdziola as an advisor, as well as Jessica Benham—who is autistic, a doctoral student at Pitt, and heavily involved in Pittsburgh disability advocacy as director of public policy at the Pittsburgh Center for Autistic Advocacy—is important, says Roger Ideishi, associate professor of rehabilitation sciences at Temple University and a national consultant for sensory-friendly programming. He’s partnered with The Smithsonian, the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra, The Warhol, and others. Best practices for sensory-friendly programs within the arts are still emerging, he notes.

The Warhol is among a growing list of local cultural organizations—Carnegie Science Center, the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra, Pittsburgh Ballet, the Pittsburgh Cultural Trust, and Children’s Museum of Pittsburgh—to program specifically with those on the autism spectrum in mind.

Since 2009, The Warhol has partnered with Wesley Spectrum High School in Whitehall to develop and deliver an intensive in-school art program that helps students on the autism spectrum or with behavioral health issues identify facial expressions, body language, and social cues. The Warhol’s pilot sensory-friendly series, made possible through the support of The Edith L. Trees Charitable Trust, the Allegheny Regional Asset District, and the FISA Foundation in memory of Dr. Mary Margaret Kimmel, is just one part of the museum’s comprehensive accessibility initiative for museum visitors with disabilities. Also available: an inclusive audio guide, tactile art reproductions and signage, and assistive listening devices in The Warhol Theater.

“What’s great about arts organizations across the country is that they’re recognizing that there’s been a group of people in society who rarely get the opportunities to experience the arts in multiple ways like many of us do—as patrons, as art makers, as art appreciators,” says Ideishi. “The Warhol is really looking closely at how we can capture the strengths of these individuals and help fill wants and needs.”

“The saying goes, if you’ve met one autistic person, you’ve met one autistic person.”

– Jessica Benham, advisory committee member

Two of the program’s crowd favorites: Artmaking in the museum’s studio, The Factory, and interacting with Warhol’s Silver Clouds. Above right, Dale Johnston tries his hand at silkscreening with help from artist-educator Heather White.

What’s success look like? “For the museum, it could be that it’s living and even expanding its mission,” says Ideishi. But he’s the first to note that measuring the outcome may be different for everybody.

“We hope to see return participants; I think we’d all be happy with that result,” he notes. “At the same time, we could see a family come to a program, stay for only a short time, and think to ourselves, wow, that’s disappointing—only to learn later from the parent that it was the best 20 minutes that family ever spent togetherin a public place. So it’s often very individualized, and that’s something organizations need to consider.”

Where The Warhol is ahead of the curve, he says, is with young adults and adult programming. Benham, who is often asked to advise on programs within Pittsburgh, says The Warhol is a needed leader in this respect. The transition to adulthood for those on the spectrum—in terms of social services, health care, employment, even entertainment—is a growing challenge.

One in six adults in the United States are living with a disability. And according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, one in 68 children has been identified with an autism spectrum disorder. As these kids continue to come of age, they’re the next generation of patrons, says Benham.

Which is precisely the reason she believes occupational therapy students, in addition to museum staff, benefit from spending time immersed in the culture of a population that is part of their clientele.

“The saying goes, if you’ve met one autistic person, you’ve met one autistic person,” says Benham. She notes that she had an interesting interaction with one of the occupational therapy students while participating in the program at The Warhol. “It turns out I had one of her family members in a class I teach at Pitt. This interaction gave the student, I hope, a moment to think about the fact that this person who is autistic is just like me, is a graduate student just like me, is human just like me. When people look at me, they often have no idea I’m autistic. There is no one universal physical attribute or singular characteristic for being autistic.”

Like many of the program’s participants, Benham says, the level of support she may need often depends on the situation and the timing.

“The Warhol’s staff is learning to interact with all people, and meeting them where they are,” says Perdziola. “And in that, there’s real value.”

Receive more stories in your email

Sign upTags:

The Inclusive Museum