You May Also Like

A Lifelong Love of Astronomy Closer Look: Walking the Land Restoring A ‘Palace of Music’

Photo: Tom Little

Saint Gilles

At 38 feet high and 74 feet long, the plaster cast of the west portal of Saint-Gilles-du-Gard, a Benedictine abbey in the south of France, still impresses today, 114 years after visitors first set eyes on it. Considered by many to be the most beautiful of all the great Romanesque portals, it only made sense that Andrew Carnegie wanted it to be the star of his collection of custom-built architectural casts. His Carnegie Museum paid the town of Gard 2,000 gold francs—about $80,000 in current U.S. dollars—for permission to make the huge cast from the original 12th-century church, a risky practice that soon would fall out of favor throughout Europe. It took three separate transatlantic voyages to transport the 195 packing cases filled with carefully crafted piece molds to New York. Two French craftsmen would spend 18 months assembling the pieces of Saint Gilles in Carnegie Museum’s newly built Hall of Architecture.

Photo: Lisa Kyle

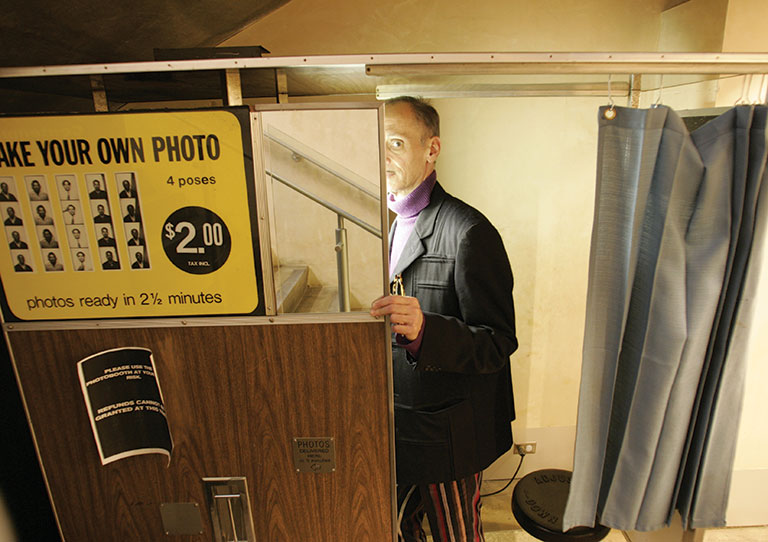

The Warhol’s Vintage Photo Booth

Andy Warhol liked the simple and quick technology of the four-for-a-quarter photo booth, and he used the photo strips to create silkscreen portraits, including of himself. The artist would encourage sitters such as art collector Ethel Skull to act out different looks and expressions, each captured in a single frame. It’s fitting, then, that on the underground level of The Andy Warhol Museum, Pop art fans can memorialize their visits inside a vintage photo booth that has been part of the museum since it opened in 1994—the four photo strips now $3. Famous visitors get in on the action, too, including John Waters, the self-proclaimed “filth elder” and Pope of Trash, seen here inside the booth in 2005. When this vintage machine is unavailable—and it happens—a modern photo booth, which allows visitors to share photos and a video of their session on Twitter and Facebook, is ready for takers on the first floor.

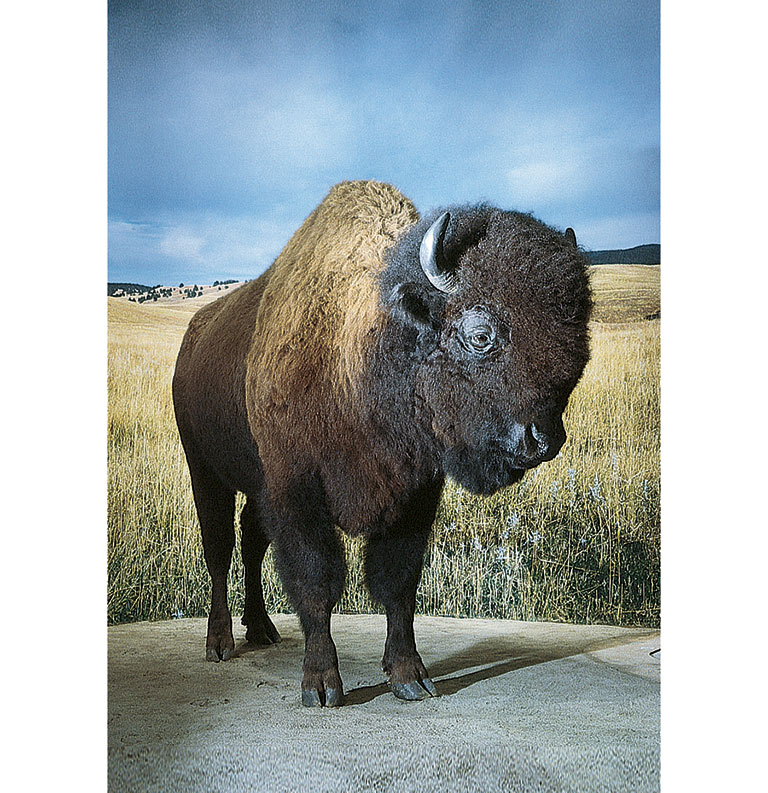

American Bison

For countless numbers of schoolchildren, the taxidermy bison standing tall in Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s Alcoa Foundation Hall of American Indians is a tour highlight because it’s real and touchable. It’s an intentional museum moment, centering the animal that is not just revered but also intertwined with the culture and spiritual lives of American Indians of the northern Plains. When planning for the hall in the early 1990s, museum staff identified the aging bison on a meat farm in nearby Mercer County. While staff knew that the bison is sacred to Native people, they didn’t understand how the relationship worked. They soon learned from Indigenous advisers that they must ask the bison if it was willing to be used for this purpose. According to Lakota legend, the bison made a pact long ago to feed the people. In return, special ceremonies are performed when bison are killed. The museum asked Rosalie Little Thunder, a Lakota spiritual leader and one of several Indigenous advisers to the museum, to perform the ceremony. With museum staff in attendance, Rosalie announced that the bison had agreed to be used for educational purposes.

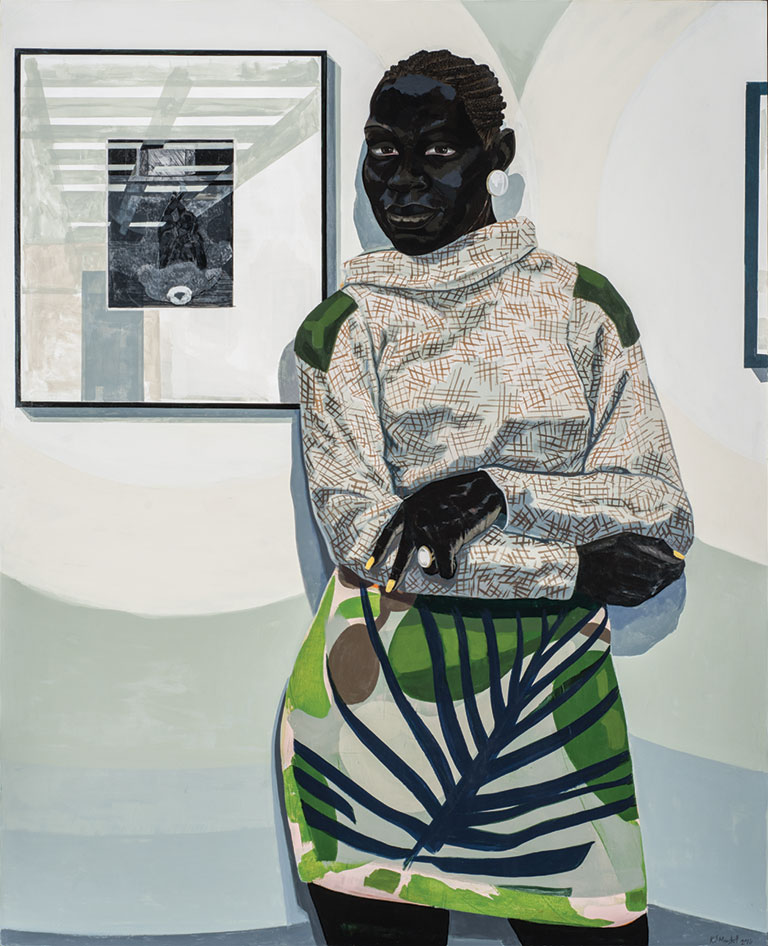

Kerry James Marshall’s Untitled (Gallery)

Considered one of the greatest living painters in America, Kerry James Marshall is best known for reinserting Black figures into the largely white historical canon of Western painting. For Eric Crosby, the Henry J. Heinz II Director of Carnegie Museum of Art, he was the one who got away. Although Marshall exhibited a far-out comic strip populated by a cast of Black heroes in the 1999 Carnegie International, the museum had failed to acquire his work. When Crosby joined the museum as a curator in 2015, he was determined to right that wrong, and in December 2016, the museum did just that by purchasing a new painting by Marshall. In Untitled (Gallery), the juxtaposition of the primary figure and the nearby photograph on the wall prompts a host of questions, Crosby wrote: “Is the subject of the painting also the subject of the photograph? Is she the artist? The curator? Or perhaps the gallerist? Is she the owner of the artwork or just an interested viewer? If Marshall’s goal has been to bring the Black figure emphatically into the field of art, and indeed into the museum, then Untitled (Gallery) takes this aim directly as its primary subject matter.”

Kerry James Marshall, Untitled (Gallery), 2016, The Henry L. Hillman Fund © Kerry James Marshall. Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner, London

Oakland Muses

Thanks to sculptor John Massey Rhind, the Forbes Avenue entrances to Carnegie Music Hall and Carnegie Museum of Natural History are hard to miss. That’s because they feature the larger-than-life bronze statues of Shakespeare, Michelangelo, Bach, and Galileo—the personification of the literature, art, music, and science found within. But often overlooked are the 12 muses who stand 12 feet tall and hover 80 feet above. Grasping the tools of their trades—among them a quill pen, a painter’s palette, a lyre, even a chemist’s flask and a fossil—these female spirits are said to provide encouragement for earthly pursuits. They were added during the first expansion of the grand building, completed in 1907.

Small snail fossils found in a Grand Staircase wall.

“Hidden” Fossils

Visitors who explore the shared Carnegie Museums and Library building in Oakland often marvel at the architecture and its head-turning multicolored marbles and limestones. What they might overlook, however, are the fossils buried in those beautiful stones. Look closely at the columns and pillars of the Grand Staircase and the walls in the Music Hall foyer and you’ll find a variety of seashell species preserved in the Échaillon limestone, mined from cliffs in the valley of the Isère River of the western Alps in southeastern France. Look closely at the beige Hauteville stone, also from France, that covers the Grand Staircase walls and the floors of the Halls of Sculpture and Architecture to discover a 5-inch-long Nerinea snail. It took Albert Kollar, geologist and longtime collection manager for invertebrate paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History, and his French colleagues years of fieldwork to authenticate the provenance of the stones.

Dirty Birds

Long before people monitored air quality through electronic devices, the soot on birds’ bellies recorded the history of air pollution. From 1880 to 2015, the soot stains on the plumage of birds preserved in museum collections in Chicago, Detroit, and Pittsburgh clearly decline in line with legislative and social changes of the 20th century, such as the switch from coal to natural gas in residential heating. Black carbon, in addition to being a public health hazard, is a major contributor to anthropogenic climate change. Thanks to the research of a pair of University of Chicago graduate students who measured the black carbon on some 1,300 birds from the collections of the Field Museum, the University of Michigan Museum of Zoology, and Carnegie Museum of Natural History, a clear picture of emissions in the past emerged, which will help to improve the accuracy of future climate scenarios. Carl Fuldner and Shane DuBay published their findings in 2017 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Because birds molt their feathers annually, the soot on the bird at the time of its death—including on these eastern towhees on view in Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s Anthropocene Living Room—is a snapshot of that year in industrial history.

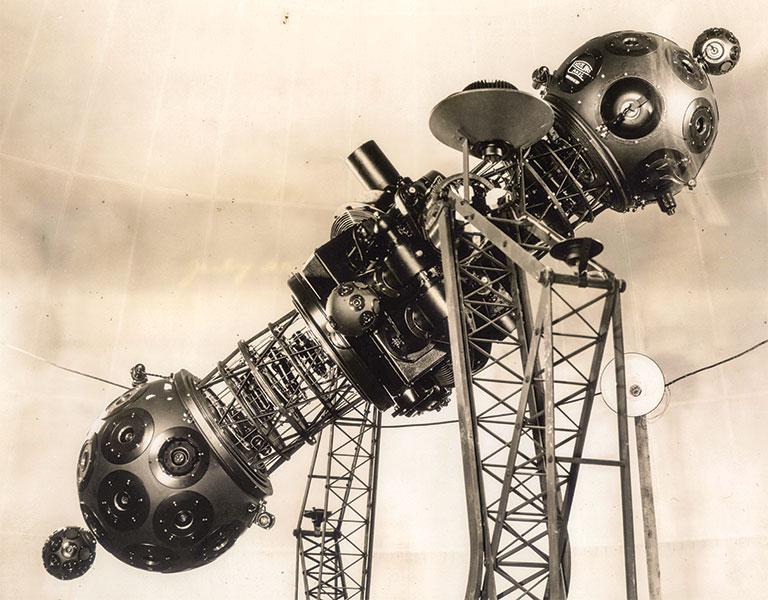

Zeiss Star Projector

The Zeiss Model II Star Projector sure could make an entrance. For more than 50 years, every show at the original Buhl Planetarium would begin with the alien-looking contraption dramatically rising from the floor. And then, as if by magic, it would illuminate the domed ceiling with the sight of more than 9,000 stars. It was the ingenuity of Carl Zeiss and the optical manufacturing company that bears his name that made it all possible. Complex clockwork mechanisms allowed the projector to accurately project the stars as they would appear at any point in time, from any place on Earth. But with the opening of Carnegie Science Center in 1991 and the ever-growing use of digital technology, its magic began to fade. Although long retired from duty, the Zeiss still looms large on the first floor of the Science Center where it stands as the focal point of a permanent interactive exhibit.

The Crowning Of Labor

John White Alexander had his marching orders: Paint an homage to the hardworking people and industrial achievements of Pittsburgh. He delivered a three-story, 4,000-square-foot mural that still surrounds Carnegie Museums’ Grand Staircase. When Carnegie welcomed crowds to his newly expanded Pittsburgh museums in 1907, the spectacle of Alexander’s The Crowning of Labor greeted them at the building’s majestic new entrance. The drama of Alexander’s mural starts on the first floor, with muscled male laborers toiling away in the steam and smoke of their industrial workplace. On the second floor, three panels tout the glory of labor, symbolized by an ascending male figure clad in a suit of armor (Andrew Carnegie, maybe?). On the third floor, Pittsburgh citizens march toward an enlightened, sunlit future, but the panels representing the fruits of their labor—art, music, literature, and science—remain blank; Alexander died before completing them. It’s hard to believe the entire mural was painted in New York City, shipped to Pittsburgh, and then glued onto the walls. In 1995, Museum of Art conservators cleaned and restored the giant mural in honor of Carnegie Museums’ centennial.

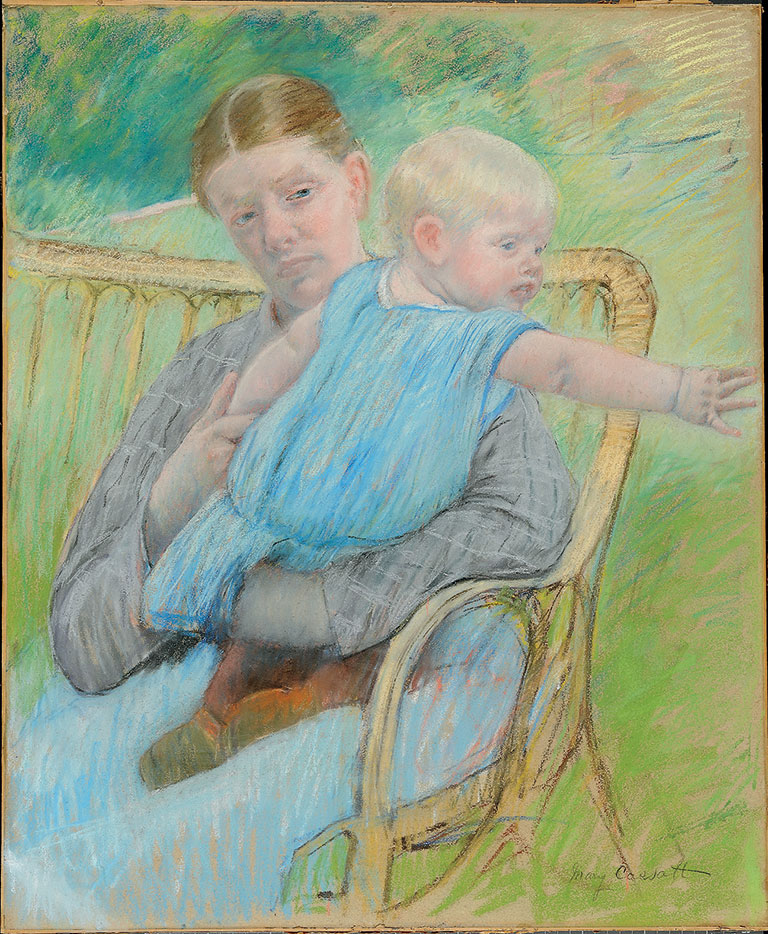

Mathilde Holding Baby, Reaching Out To Right

In 2011, Carnegie Museum of Art added this major pastel by Mary Cassatt to its collection. Mathilde Holding Baby, Reaching out to Right represents not only a medium for which the native Pittsburgher is renowned, but it’s also an early, energetic example of the artist experimenting with what would become her signature subject: mother and child. The sitter is Mathilde Valet, the artist’s housekeeper and companion for many decades. While her hands are intertwined, Mathilde’s expression is ambiguous, and the baby appears to be reaching for something just beyond the frame—a compositional strategy the artist used across a range of subjects, in a sense teasing the viewer. Cassatt was one of three women and the only American to show with the French Impressionists. The museum collects her work in depth, with a painting and 19 prints also part of its collection.

Mary Cassatt, Mathilde Holding Baby, Reaching out to Right, c. 1889, Carnegie Museum of Art, Heinz Family Fund, Robert S. Waters Charitable Trust Fund, Major Paintings Acquisition Fund, Alan G. and Jane A. Lehman Fund, Alice and Jim Beckwith Art Acquisition Fund, and Foster Charitable Trust Fund

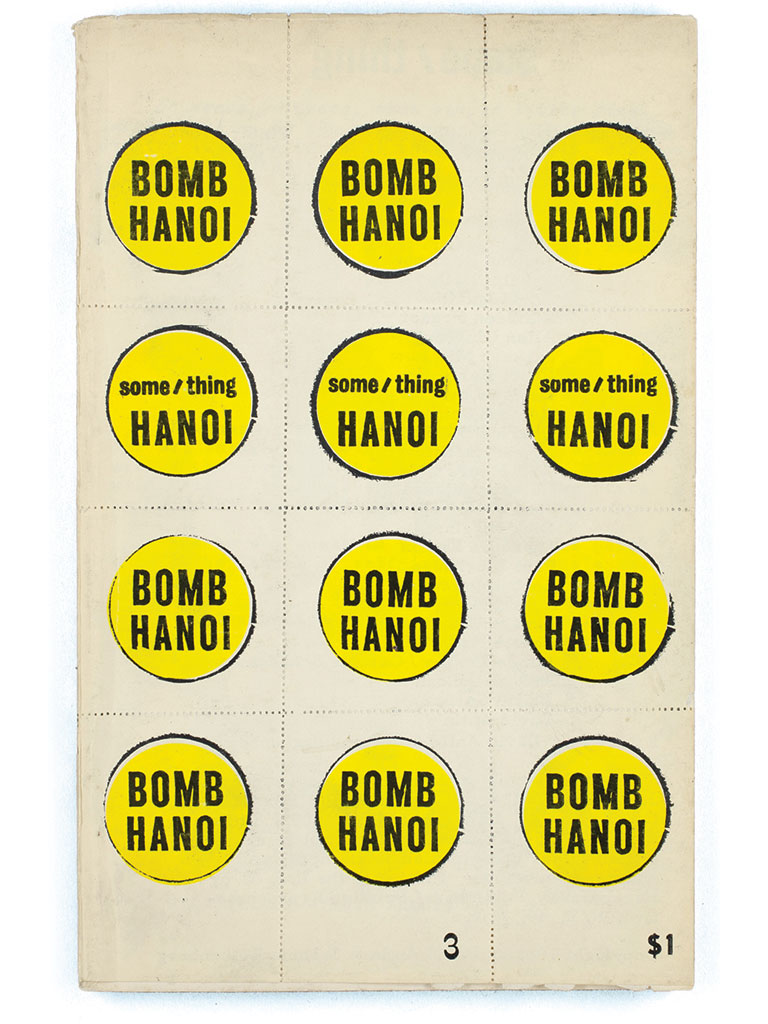

Cover Of Some/Thing, Vol. 2, No. 1

Andy Warhol was famously ambiguous when asked about the meaning or intent of his artwork. But if you pay attention, says Matt Gray, manager of The Warhol’s archives, you can piece together many of the artist’s social and political beliefs. When David Antin, the editor of underground poetry magazine some/thing, approached Warhol about designing the publication’s winter 1966 cover, an issue all about the Vietnam War, Antin suggested that the artist use a popular pro-war slogan—with a twist. The idea was to get war supporters to pick up the magazine and read it, Antin wrote in Design Observer, only to be greeted by anti-war poetry by the likes of Allen Ginsberg. Warhol, who originally pitched a Vietcong flag for the cover, didn’t disappoint. He created perforated sheets of real glue-backed stamps for the front and back covers that scream “BOMB HANOI” and could be conveniently torn out and pasted on telephone poles or subway walls.

Andy Warhol (cover design), Some/thing – Vol. 2, no. 1 (Winter 1966), 1966, The Andy Warhol Museum; Gift of Jay Reeg

Cecil

Cecil, the “guard dog” for Andy Warhol’s Factory, appeared in photos with the artist’s Superstars and in his series of dog paintings. Procured from an antiques shop around 1970, the stuffed Great Dane was said to have belonged to legendary film director Cecil B. DeMille, hence his name. But as a canine photographer and genealogist discovered two decades later, Cecil’s pedigree was far more impressive. His true name was Ador Tipp Topp, and he worked the dog show circuit, taking home the 1924 Westminster Kennel Club Best of Breed crown. The showstopper died in 1930, and his taxidermied remains were gifted to the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History, where the specimen obediently stayed until the mid-’40s. His afterlife journey eventually took him to the antiques store, where he acquired the famous name and famous owner. When Warhol died, Cecil found his eternal resting place at The Andy Warhol Museum.

Champion Ador Tipp Topp (“Cecil”) 1921-1930, 1931, The Andy Warhol Museum; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

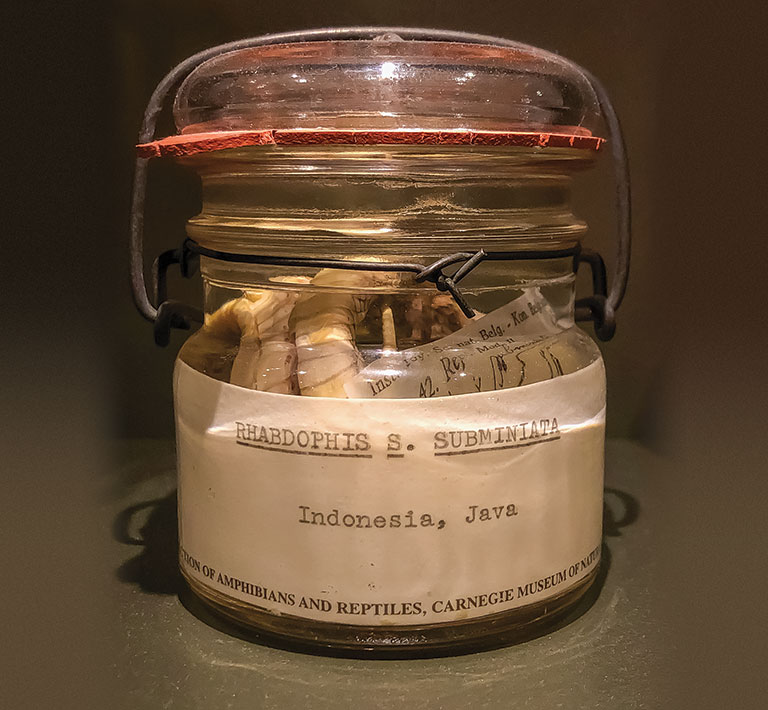

Red-Necked Keelback, Collected In 1872

In its wonderfully creepy Alcohol House, Carnegie Museum of Natural History boasts about 230,000 reptiles and amphibians from 160 countries—95 percent of them fluid-preserved in jars. Each is a scientific time capsule, which is why researchers across the globe use them to study the ecology and evolution of species and their environments. Jennifer Sheridan, curator of amphibians and reptiles at the museum, recalls sleuthing for specimens from Southeast Asia when she came across a common snake, called Rhabdophis subminiatus (or red-necked keelback), that hailed from an uncommon locality—Java, Indonesia. “The exact location detail is what caught my eye,” Sheridan notes, “the island of Ternate, where British naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace was when he wrote his famous letter to Charles Darwin in 1858, explaining to Darwin his idea of evolution by natural selection.” While traveling across Indonesia, Wallace had noticed a distinct change in the species of plants and animals found in two neighboring island groupings. Darwin would later jointly publish his own work on the topic alongside Wallace’s. While the date of the specimen, 1872, is 10 years shy of being linked to Wallace’s work on the island (he left a decade earlier), it’s among the oldest in the museum’s collection.

Freshwater Seal

In 1935, Carnegie Museum of Natural History Curator of Mammals J. Kenneth Doutt first saw evidence of an uncommon find while doing fieldwork in Quebec, Canada. He observed an Inuit man carrying a sealskin bag with fur he had never seen. There were local rumors of a freshwater seal, but it would take another three years and a well-planned winter expedition to find this mammal, previously unknown to science. Joined by Curator of Ornithology Arthur Twomey and Inuit guides, they trekked into the poorly mapped interior of Quebec to a chain of freshwater lakes where the elusive Ungava harbor seal, an uncommon freshwater relative of the better-known Atlantic harbor seal, was said to live. For the next eight months, they, too, called the Ungava Peninsula and Hudson Bay home. Upon their triumphant return to Pittsburgh, the pair brought with them the holotype, or the original specimen used to name the new subspecies of freshwater seal. In the 1980s, to help inform the new Wyckoff Hall of Arctic Life, museum staff retraced Doutt’s steps, and met Inuit people who remembered the 1938 fieldwork fondly.

E-Motion

Is it searching for signs of alien life in space? Not quite. Also known as the weather cone, Carnegie Science Center’s trademark E-Motion Cone was designed by New York architect Shashi Caan and lighting designer Matthew Tanteri. Hard to miss at 66 feet wide and 44 feet tall, the illuminating sculpture was installed in 2000 atop The Rangos Giant Cinema as a weather beacon for Pittsburgh. Its computerized lighting system, controlled by the Science Center’s weather partner, WTAE-TV, displays different colored lights based on the weather forecast: red for warmer weather, blue for cooler, green for no change, and yellow for a rain or snow warning.

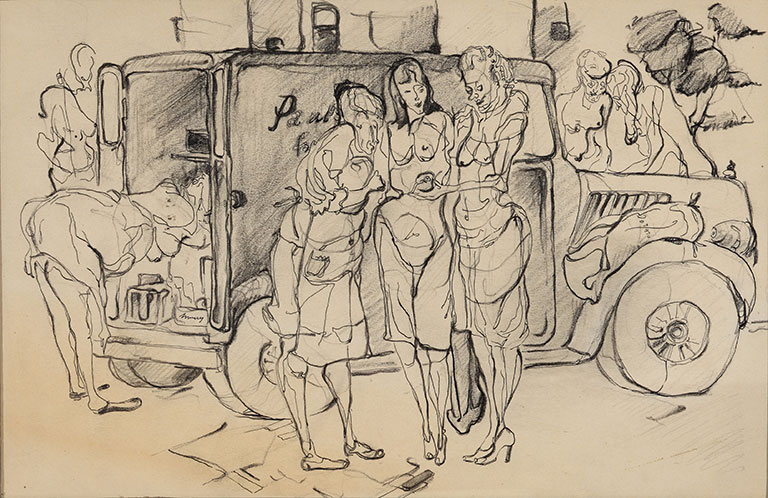

Andy Warhol’s Women And Produce Truck

Before he became a household name, Andy Warhol almost flunked out of art school at Carnegie Institute of Technology, now Carnegie Mellon University. At the end of his freshman year in 1946, Warhol’s instructors put him on academic probation, calling his style too primitive. That summer, the artist honed his skills by following brother Paul, who sold produce from a truck. Traveling the streets of his childhood neighborhood of South Oakland, Warhol sketched the women who bought the fruits and vegetables. While the drawings were considered conformist by Warhol’s standards, they were in line with what was considered beautiful at the time. Now on view at The Warhol, the early sketches helped Warhol establish himself as a star student. That fall, he won the Martin B. Leisser Prize and had the works exhibited in the college’s fine arts gallery.

Andy Warhol, Women and Produce Truck, 1946, The Andy Warhol Museum; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

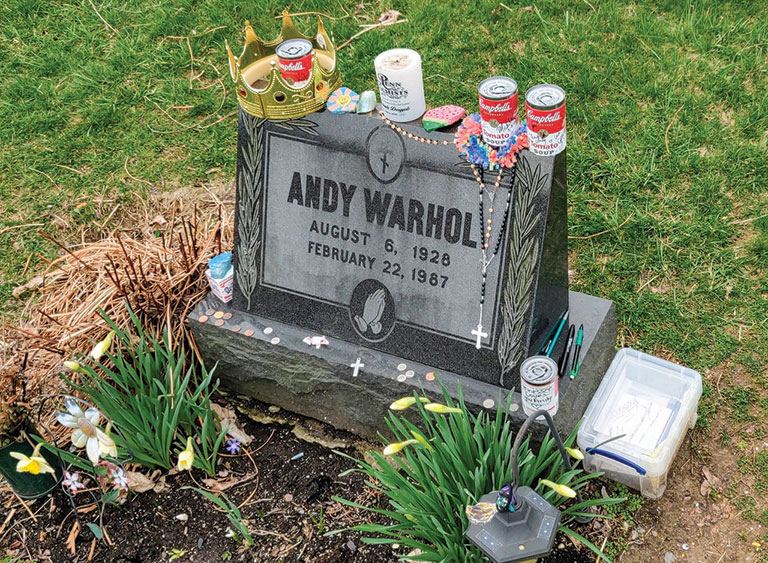

Andy Warhol’s Gravesite

To the surprise of many, Andy Warhol is buried near his parents, Julia and Andrej Warhola, in the small St. John the Baptist Byzantine Catholic Cemetery in the suburb of Bethel Park, just south of Pittsburgh. Long a mecca for fans carrying with them Campbell’s soup cans, rosaries, personal letters, birthday cakes, and more, in 2013 The Andy Warhol Museum teamed up with EarthCam to make the gravesite viewable 24/7. At one time, the website hosting the live webcam allowed viewers to order offerings, and takers were given a time of day to observe their delivery. It’s all very Warholian—watching the final resting place of a man who liked to watch. Warhol, after all, pioneered motion pictures of motionless subjects and foretold, for good or bad, reality TV. In 2020, artist Madelyn Roehrig published Andy, Can You Hear Us?, a quirky celebration of the famous artist’s vibrant afterlife as depicted by the inspired visitors to his gravesite since 2009.

Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood Home

You can’t find it on a map. In fact, the only place where the Neighborhood of Make-Believe exists—beyond our imagination, of course—is within Carnegie Science Center’s Miniature Railroad & Village®. The creation of Pittsburgh’s own Fred Rogers, Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood first aired on WQED in 1966. Over the course of 30-plus years and 895 episodes, the landmark show was an educational haven for children and their parents. On March 19, 2005, the day before what would have been Rogers’ 77th birthday, a tiny replica of Mister Rogers’ house—made entirely out of beeswax—found a home in the popular Science Center exhibit. There, the red trolley perpetually passes by as Fred himself, clad in his signature red cardigan and blue sneakers and flanked by two children, sits on the front-porch swing.

Pirate Parrot The Science Experiment

On October 5, 2015, days before the Pittsburgh Pirates played their wild card game against the Chicago Cubs, the Pirate Parrot flew into the stratosphere and back. Not the real team mascot; rather, a plush Pirate Parrot toy launched inside a weather balloon from PNC Park, all in the name of out-of-this-world science. Students strapped the stuffed bird to the balloon as part of a collaboration between Carnegie Science Center’s Science on the Road program and education-based company StratoStar, launching the bird to an altitude of 96,000 feet—about three times higher than most commercial airplanes fly. High-definition cameras caught every minute of the flight, as it peaked 18 miles above Earth’s surface, the curvature of the planet visible. The helium-filled balloon carried sensors measuring temperature, altitude, speed, and spin rate before popping, and a parachute guided the parrot back to Earth, where a team recovered it from a tree in Cranberry Township, about 15 miles from the ballpark.

Fab Lab Hand

In 2016, Carnegie Science Center’s BNY Mellon Fab Lab partnered with e-NABLING the Future, a global community of more than 1,500 volunteers, to make 3D-printed prosthetic hands. After a few months of training in the Science Center’s popular maker space, about a dozen area high school students got the chance to craft the prosthetic hands, which look like they might belong to a superhero. The students then led a group of community volunteeers in assembling the fully functional limbs, which were sent free of charge to children throughout the world who are missing all or part of their hands due to injuries from violent conflicts or disease.

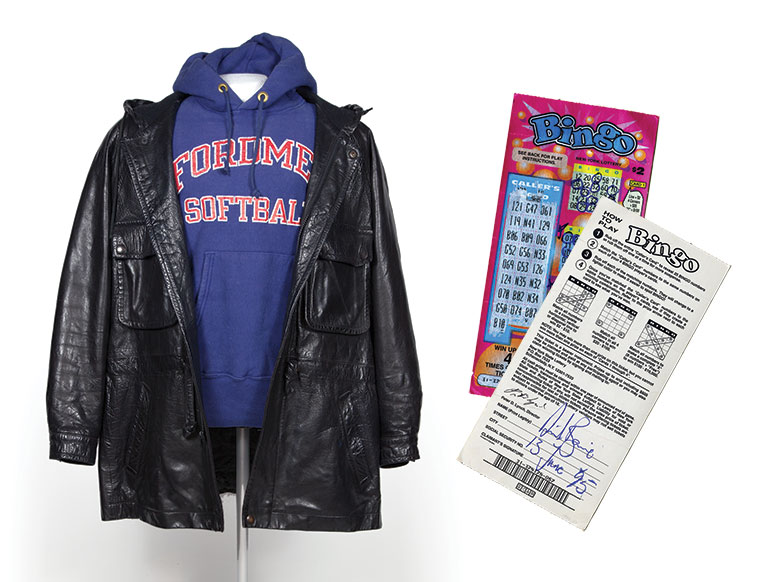

Andy Warhol’s Leather Jacket With David Bowie Lottery Ticket

Tucked inside Box C25 (C stands for clothing) in The Andy Warhol Museum archives are the last personal items Andy Warhol touched, having worn or carried them with him to New York Hospital in Manhattan, where he died on February 22, 1987, two days after having his gallbladder removed. Among the items: documents from the hospital and this hooded Calvin Klein leather jacket, the receipt for the artist’s $2.40 taxicab ride to the hospital at 4:48 p.m. on February 19 folded inside its pocket. It’s the same jacket Warhol wore one month earlier to the opening of his final exhibition during his lifetime, Warhol—Il Cenacolo-, at Milan’s Palazzo delle Stelline (underneath it he sported a hoodie for the softball team of Ford Modeling Agency). The jacket would be worn by one other person after Warhol’s passing—David Bowie, when in 1996 the glam rock icon played Warhol in the film Basquiat. The museum agreed to lend one of Warhol’s wigs and the leather jacket to Bowie, a big fan of Warhol’s. When he returned it, placed inside the pocket this time: a New York state bingo scratch-off ticket (a $5 winner!), signed and dated by Bowie.

Calvin Klein, Calvin Klein hooded leather jacket, 1980s, The Andy Warhol Museum; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

Lottery ticket (Bingo, New York Lottery, June 13, 1995), 1995, The Andy Warhol Museum; Gift of David Bowie

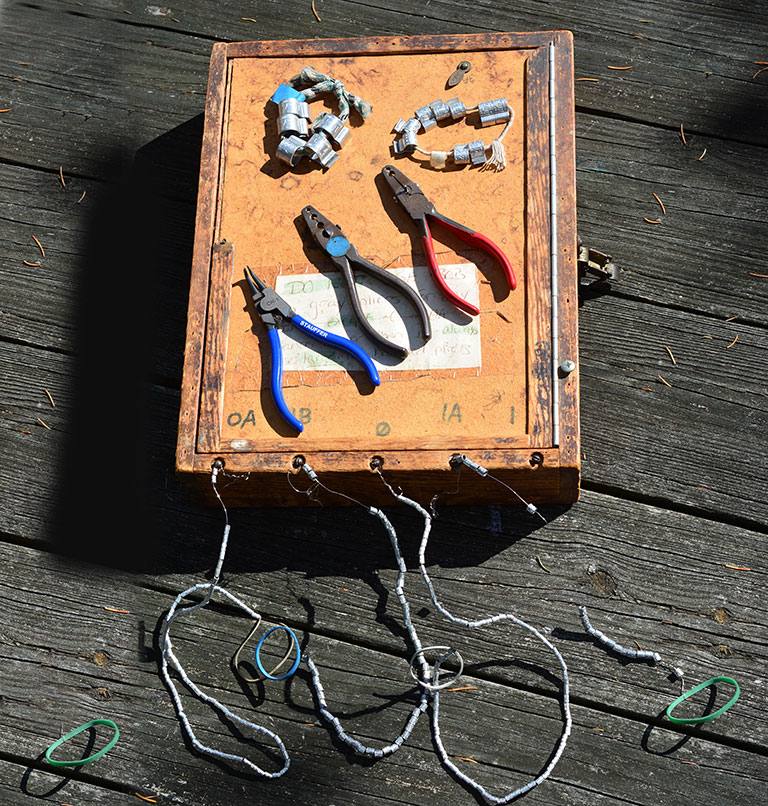

Bob Leberman’s Banding Kit

This spring, Powdermill Nature Reserve’s world-renowned bird-banding program will turn 60, having captured and released some 200 species of nearly 800,000 individual birds! This original banding kit was used by late program founder Bob Leberman, a largely self-taught ornithologist who in 2004 retired after serving 43 years as senior bird bander. In the early years, Leberman had no physical lab, so Albert C. Lloyd, Leberman’s first banding assistant, designed and built this banding box as a convenient way for Leberman to carry supplies and later to organize the tiny silver bird bands at a stationary desk. He would attach the most-used band sizes to the screws on the outside of the box, and store larger, infrequently used sizes inside, along with the pliers he used to gently close the bands around birds’ legs. Finally, he would include the all-important data sheets used for recording a wealth of information about each capture—species, age, sex, wing length, fat deposits, and body mass. Today, the same process still takes under a minute, with the specs for each bird entered directly into a database.

Hoops

Kids and grown-ups alike stared in awe at Hoops. The 3-ton, orange robotic basketball arm could do what no human could do—make nearly 94 percent of its free throws. In its center court spot at Carnegie Science Center, Hoops was a phenom, effortlessly making behind-the-back, 22-foot throws. Built in 1995 as a welding arm for the automotive industry, it debuted at the Science Center the following year as the world’s first professional-grade, basketball-shooting robot. After making road trips as a loaner to other museums, Hoops returned home in 2009 as a star attraction of roboworld. But like an aging athlete, time took its toll on Hoops, its accuracy eventually slipping to about 60 percent. The museum struggled to find replacement parts for the aging robot, so in 2017 it was upgraded to a new, sleeker robotic arm, now dazzling a new generation.

Warhol’s Pinhole Sunglasses

Andy Warhol was nearsighted, and in the 1950s he tried a new unproven method of corrective vision: pinhole sunglasses, similar to a pair of dark sunglasses with multiple small pinholes punched through each lens. Makers of the eyewear claimed in mass-market advertisements that they would improve vision by strengthening eye muscles, but the method was debunked shortly after Warhol began wearing them. Discovered in the museum’s archives only recently as staff conducted research for Blake Gopnik’s 2020 biography Warhol, the pair of damaged sunglasses was among the final batch of archival material The Warhol acquired from The Andy Warhol Foundation, Inc., in 2014, the same year the foundation liquidated its art collection. A staff member and Gopnik took the lenses of the glasses to an optometrist in Market Square to learn more about them. It’s likely vanity motivated Warhol to give the eyewear a shot. Around the same time, he began doctoring photographs of himself and had the skin on his nose shaved.

Pinhole glasses, 1950s, The Andy Warhol Museum; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

Gazelle Lounge Chair

When you explore Carnegie Museum of Art’s much-loved collection of chairs, what draws you in? Their material or functionality? Based on looks alone, Rachel Delphia, the museum’s Alan G. and Jane A. Lehman Curator of Decorative Arts and Design, says one of her favorites is this whimsical Gazelle chair, named for its gracefully abstracted animal silhouette. California designer Dan Johnson made a series of furniture pieces in which this animal, cast in metal, forms the supporting elements. Can you spot the gazelle? Start at the top, says Delphia, to find the antlers, the elongated face, and the animal’s stance.

Dan Johnson, Gazelle lounge chair, 1956-1960, Carnegie Museum of Art, Women’s Committee Acquisition Fund

Receive more stories in your email

Sign up