Deep in the recesses of a warehouse a couple of miles away from Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Oakland lie the humble early works of a master artist.

They are only charcoal and chalk sketches, kept in a flat file drawer. Most of the subjects are woodland creatures depicted in a style that you might see in children’s books. One sketch shows a groundhog happily napping. Another has a groundhog throwing a hissy fit to rebuff a hungry fox.

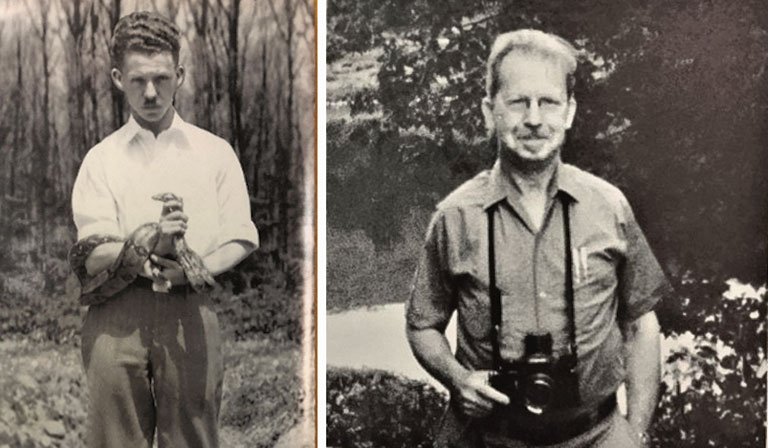

It’s been seven decades since the artist, Jay Matternes, made them while he apprenticed with Ottmar von Fuehrer, the chief staff artist of Carnegie Museum of Natural History in the 1950s. Matternes would go on to have a storied career in natural history illustration as a painter for the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History.

Even now, at the age of 91, Matternes recalls sketching all manner of mammals and more for Carnegie Museum of Natural History. But he never expected anyone would have kept his art.

“I always assumed that the work I did there had long since ended up in a dumpster or a landfill,” Matternes exclaims in surprise when reached by phone from his home in Fairfax, Virginia. “I’m very pleased they preserved them.”

The groundhogs he sketched for children as part of the museum’s education programming are included among roughly 100 pieces of his art depicting animals ranging from elk to warthogs. They even include working sketches he did for a museum display titled “Tide Pool Universe” that are part of a little-known but rich collection of naturalist art at the Museum of Natural History.

The art collection includes thousands of prints, drawings, paintings, and photographs created by professional artists and illustrators such as Matternes, and lesser-known local artists.

Photo: Joshua Franzos

Photo: Joshua FranzosAlthough some works from the collection have been displayed in past exhibitions, most have never been seen by the public. But lately, the naturalist artworks have been getting some attention from Deirdre Smith. A scholar of contemporary art and visual culture who joined the museum in 2022 as an assistant curator, Smith has been exploring the collection for what it can teach audiences today about the history of the museum, as well as the intersection of art and science. Smith, who also teaches museum studies at the University of Pittsburgh, gave a lecture last year to highlight some of the pieces from the collection. She hopes to feature some of its hidden treasures one day in an exhibition.

“The Natural History Art Collection is visually quite lush and varied,” Smith says. “But more importantly, it archives fascinating stories about the history of art and image making, the history of science, the history of our museum, and the history of animal and plant life.”

The history of the collection extends back more than a half century to a longtime director of the museum and an essential figure in the institution’s history, M. Graham Netting.

Born in Wilkinsburg in 1904, Netting was curator of the Section of Amphibians and Reptiles until he took over as museum director from 1954 to 1975. Early in his tenure, the well-connected conservationist and environmentalist helped create the museum’s Laurel Highlands research station, Powdermill Nature Reserve.

Powdermill is among Netting’s most important contributions to the museum, but a lesser-known part of his legacy is the art collection he began assembling late in his career. He’d developed an interest in photography and art, collecting pieces both for his personal collection and on behalf of the museum. In 1973, Netting used a $25,000 grant from the Scaife Family Charitable Trusts to formally start what was then called the “M. Graham Netting Animal Portraiture Collection.”

He grew the bulk of the collection after his retirement, mostly in the 1970s and early 1980s, to what’s now nearly 2,000 items—drawings, paintings, prints, photographs, and more by scientists, naturalists, illustrators, and other skilled makers. In a November 1979 story that appeared in Carnegie magazine, Netting wrote that his goal in creating the collection was to preserve these purchases, gifts, and museum ephemera “for the enjoyment of future generations of nature lovers.”

Some of it was exhibited in 1976 and 1978, but for most of its existence the collection has been quietly cared for in off-site storage where it is rarely viewed by the public.

Hidden Treasures

Netting’s taste in art reflected his personal interests and connections with sportsmen’s and conservation groups, Smith says. “It leads to some of the eclectic nature of the collection. But I think it’s eclectic in the best way.”

Moving between the 7-foot-tall steel storage cabinets, Smith can show off everything from lifelike wooden duck decoys, including a mallard couple crafted by renowned Canadian carver Ken Anger, to Matternes’ sketches, some of which were published in a February 1980 Carnegie magazine cover story on groundhogs (complete with recipes).

Photo: Joshua Franzos

Photo: Joshua FranzosDuck decoys crafted by renowned Canadian carver Ken Anger.

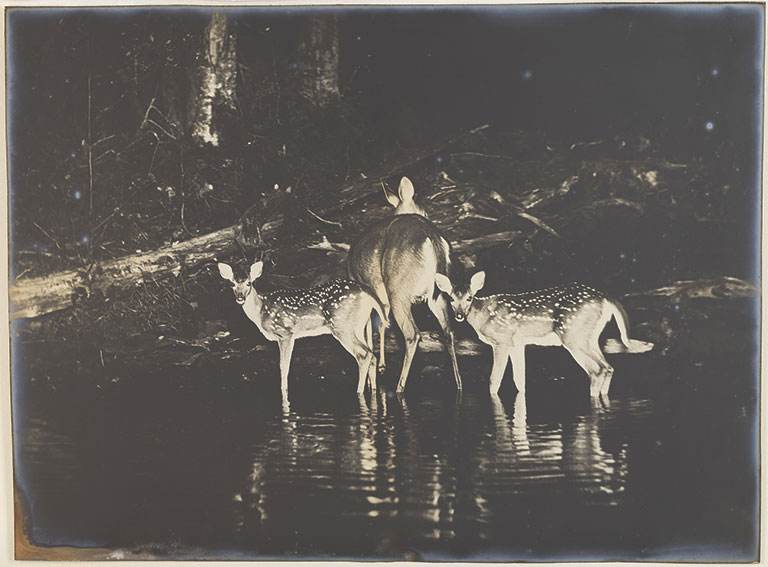

She slides from one drawer a 23-by-27-inch silver gelatin print of a deer family that looks freshly made, and certainly more recent than 1892. That’s when the haunting photo Doe with Twin Fawns was photographed at night on a Montana shore by George Shiras III, a native of Allegheny City (now Pittsburgh’s North Side neighborhood) and a pioneer in wildlife photography because of his use of flash technology for nighttime shots.

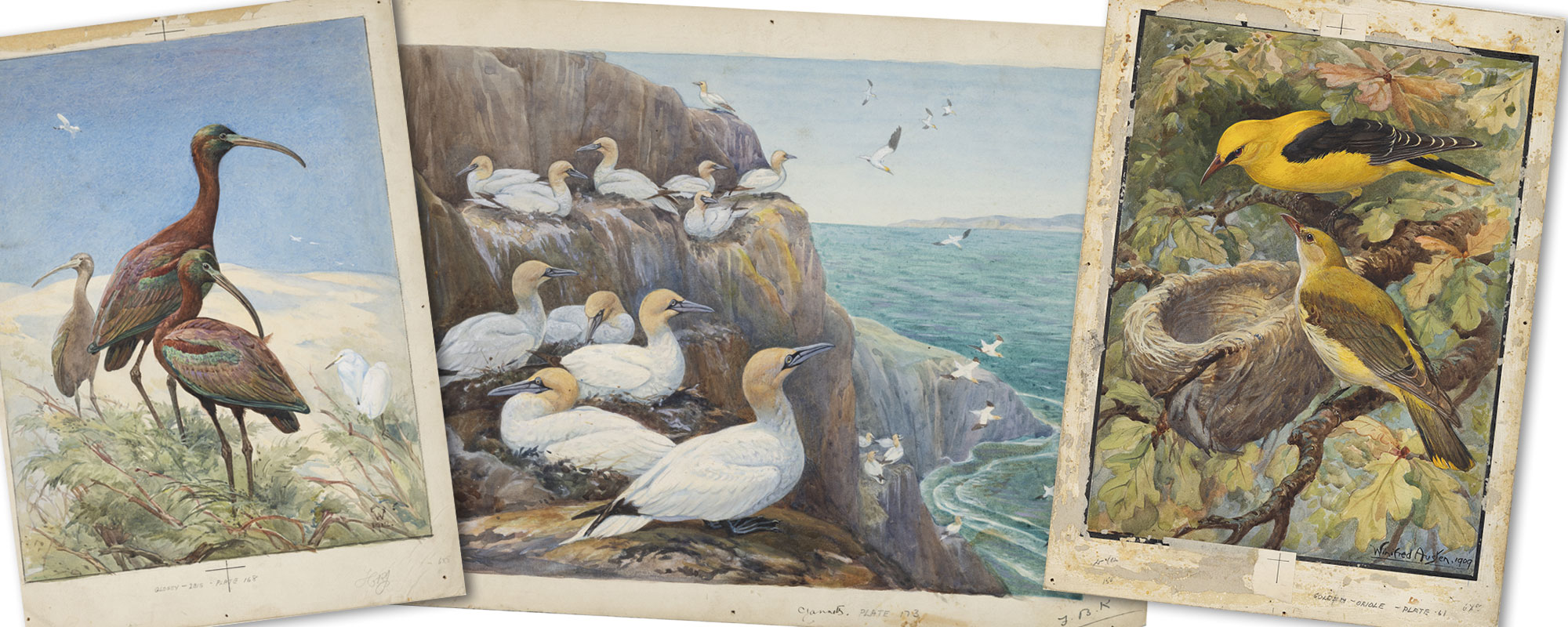

The collection also contains many fine paintings of birds. The luminous 14.5-by-10.5-inch watercolor Golden Orioles depicts a bright yellow male and a more neutral-toned female at a nest. It’s one of 20 paintings that Netting purchased for the collection by Winifred Austen, an art world pioneer as one of few women working in the field of naturalist illustration at the turn of the 20th century. She painted Golden Orioles for F.B. Kirman’s The British Bird Book, for which she was the only woman hired.

“They’re really among the most beautiful and successful images that we have in the entire collection,” Smith says.

Many of the illustrations in the collection were created to be sold as fine art prints. One of Smith’s favorite items is a matted, plastic-sheathed, 23-by-19-inch watercolor of a mud salamander that’s much more vibrant and beautiful than its name sounds. It was painted in the early 1970s by David M. Dennis, who, like many artists in the collection, was a prolific producer of illustrations for scientific articles and field guides.

Smith says you can see Netting’s art expertise and “shrewd hand” in choosing Dennis’ salamander because of its interesting composition: a bird’s-eye view of the S-shaped reddish salamander on a bed of brown leaf litter with a black beetle. Netting was not shy about sharing his opinion of artwork, either. In correspondence with Dennis, the two go back and forth at length over which works the museum will acquire, with Netting occasionally critiquing the artist’s skills.

The collection’s oldest artifacts were purchased in 1918 by Netting’s predecessor, museum director William Jacob Holland. They include 50 watercolors that Henry W. Elliott painted in the 1870s documenting the Alaskan fur seal population and trade on the Pribilof Islands. Elliott’s work led to conservation efforts to protect the fur seal from over-hunting, an early example of how image making and viewing can be not just science but also activism.

But Smith says she most values the art made by and connected to people who worked at the museum, such as Matternes and von Fuehrer. The latter went on to work as chief staff artist until 1965, creating volumes of art with his wife, Hanne, including background paintings for dioramas still on view in the Hall of North American Wildlife such as that for the Woodland Caribou Group. His gouache studies for the display, which are based on photographs taken on a museum expedition to the Canadian Rockies, are also part of the Natural History Art Collection.

The talented Matternes originally hoped to succeed von Fuehrer as the museum’s chief staff artist. But von Fuehrer wasn’t ready to retire when Matternes graduated, so Matternes moved on. He wound up at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, where he painted murals of extinct mammals and illustrated prestigious publications such as Science, National Geographic, and Scientific American. His career was the subject of a book published in August 2024, Jay Matternes: Paleoartist and Wildlife Painter.

Matternes still has fond memories of his beginnings in Pittsburgh, including going to nearby Schenley Park with the von Fuehrers to run their boxer, Blitz. Of course, they took their paint boxes to capture the landscape en plein air. “I worked very hard and those were excellent years for me,” Matternes recalls fondly, happy to hear how much of his work is preserved. “I thought I would be forgotten.”

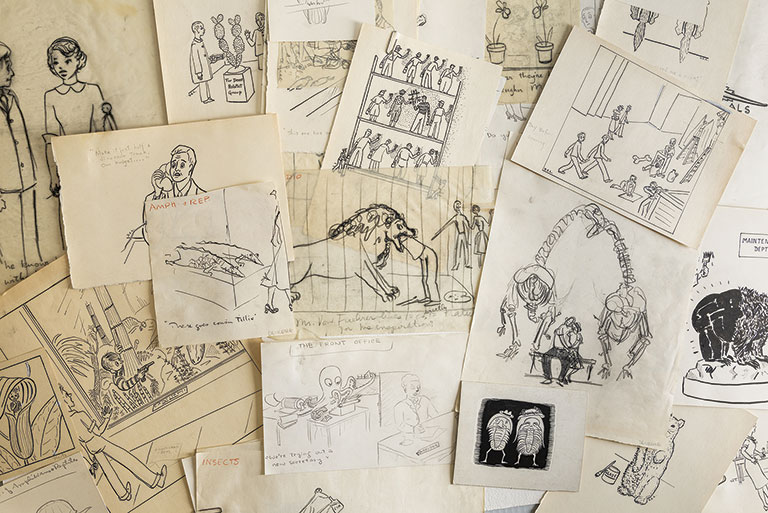

Among the contributions to the collection from lesser-known artists was what Smith called a “real treat of a find” of a cartoon poking fun at von Fuehrer by a long-ago staffer who signed it “Deirdre.” In addition to fine art, Netting intended for the art collection to store institutional ephemera like these drawings, which can now speak to artmaking as part of the daily life, and fun, of working at the Museum of Natural History.

“Art has a unique power to make all of these histories and subjects vivid, again and again,” Smith notes.

Receive more stories in your email

Sign up