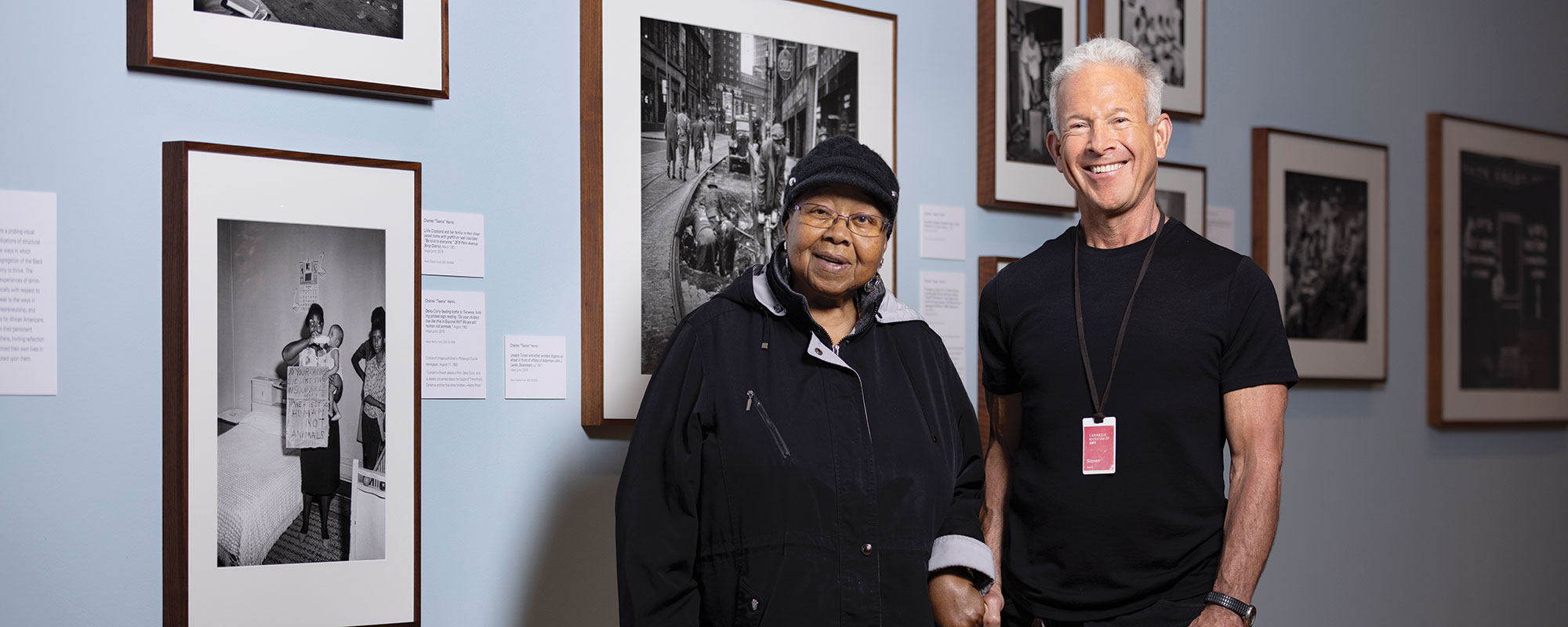

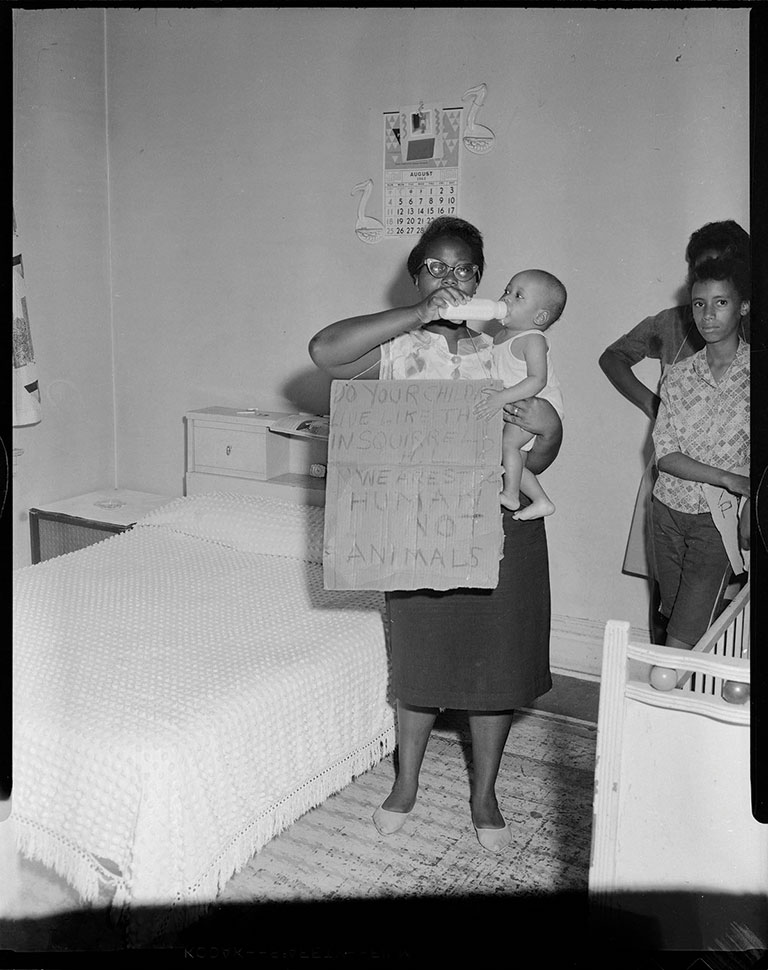

Daisy Curry (Simmons) carefully inspects the black-and-white photograph hanging in Carnegie Museum of Art’s Teenie Harris gallery, quietly taking it all in. It’s her younger self, 58 years ago—her 7-month-old son Terrence in one arm, feeding from a bottle, a hastily written protest sign hung around her neck.

“I remember sitting down and wondering what I could make a sign with,” Curry recounts, slowly, wistfully. “I found this cardboard box and started ripping it up.”

It was August 17, 1963, and the tenants in her Homewood apartment building had banded together to protest its deteriorating conditions. Rumor had it The Pittsburgh Courier was sending ace photographer Teenie Harris to document the protest.

As for the young Mrs. Curry’s choice of words for her sign, she says, simply, “I was just trying to think of what I could write that would mean something. At the time, Squirrel Hill was THE place. You wouldn’t [as a Black person] be caught dead there. If you were in Squirrel Hill, you were either working or just passing through.

“I worked for someone there for a while, and I would think, ‘Wouldn’t it be nice to live up here and have this nice house, and this nice garden?’” she says. “So, that’s why I wrote what I did—it just popped in my mind. God put it in my head, and I put it on the paper.”

Charles “Teenie” Harris, Daisy Curry feeding bottle to seven month old Terrence and holding protest sign reading “Do your children live like this in Squirrel Hill? We are still human not animals,” in small bedroom, August 1963, Heinz Family Fund, Copyright:© Carnegie Museum of Art, Charles “Teenie” Harris Archive

Curry thought her quiet protest had ended there. She was busy raising a houseful of kids, moving out of the Brushton Avenue apartment building with her husband and six (soon to be seven) children not long after the protest. Ten years later, she would earn a nursing degree—she still vividly recalls her kids yelling, “That’s my mama!” at the graduation ceremony—and over the next 20 years she cared for patients at four state-run psychiatric hospitals.

“I never paid that day another thought,” Curry says.

She never knew The Pittsburgh Courier had published Teenie Harris’ photo of her along with a story about the protest. And she had no idea that, nearly six decades later, that same photo hung from the wall of her hometown art museum.

That is, until she got a phone call from Steve Zelicoff in December 2021. He was looking for the Daisy Curry pictured in the photograph at Carnegie Museum of Art. “I said, ‘Are you sure it’s me?’ I was shocked,” Curry recalls. “And then he described me in the photo, holding a baby.”

Zelicoff, a longtime docent at the Museum of Art, had looked at that image countless times. “I love this photograph. I use it on every one of my tours. It is so poignant, as is much of Teenie Harris’ work. He exposed so many issues that people of that time were facing.”

“Visitors come into the gallery and comment on this photo all the time,” says Charlene Foggie-Barnett, community archivist for the Teenie Harris Archives at Carnegie Museum of Art. “It’s one of the most powerful photos in the collection, and one of the most requested from outside publications.

“This is a wonderful example of how Teenie’s photos bring people together in such poignant ways,” she says, “and Steve’s kindness deserves to be acknowledged.”

Since acquiring the Teenie Harris Archives in 2001, the museum has been on a mission to identify as many of the photos’ subjects as possible and contact them for context. But when Zelicoff asked Foggie-Barnett about Daisy Curry, who is identified on the gallery label thanks to the article in The Pittsburgh Courier, he learned the museum had yet to find her. So Zelicoff took on the task.

The work of Teenie Harris, particularly the photographer’s images of life in the city’s Hill District, has always hit home for Zelicoff. “I spent a lot of my early childhood in the Hill District,” he says. “My parents were Polish immigrants and were raised in the Hill District. My mother’s sister still lived in the family home when I was growing up, and on Saturdays my mother would drop us off at the family house and we would run wild in the neighborhood. I loved those days.”

After some online searches, Zelicoff not only spoke with Curry by phone but visited her at her home in Duquesne, presenting her with a framed print of her 1963 photograph.

“Once I knew you were living nearby, I had to meet you!” Zelicoff exclaims to Curry as he and Foggie-Barnett give a tour of the museum’s Teenie Harris gallery to her and her husband, Lewis Simmons (her first husband passed away in 2001). Zelicoff had wanted to bring Curry to the Teenie Harris gallery since visiting her, and today it’s finally happening.

“This is a wonderful example of how Teenie’s photos bring people together in such poignant ways.”

-Charlene Foggie-Barnett, community archivist for the Teenie Harris archives at Carnegie Museum of Art

“This is what Teenie does best: teach the truth of how we lived as African Americans,” Foggie-Barnett says to the visiting couple. They move around the gallery, stopping at an image of a civil rights protest in downtown Pittsburgh. “And this is what it looks like to support a national civil rights movement here in Pittsburgh.”

But not all protests are large, and loud, and public, she adds. “They can be small, silent protests, in a Homewood apartment building, by someone like Daisy Curry.”

As they leave the Teenie Harris gallery and pass other docents, Zelicoff shouts, “This is Daisy Curry!” They all flock to meet her.

Still not so sure about her iconic status at the museum, Simpson shakes her head. “Never in my wildest dreams …”

Receive more stories in your email

Sign up