Landscape photographers canvassed the West in the 1860s and ’70s, bringing vivid, deep-focus depictions of mountains, canyons, and rivers to an awestruck American public. But they were more than artists. They were participants in a project more sweeping than the valleys and vistas they documented: the westward expansion of the United States, and the transformation of an environment that had not yet been industrialized.

Carleton E. Watkins, whose photographs of Yosemite Valley and the Columbia River secured his reputation as one of that era’s defining artists, worked in Oregon on behalf of a powerful river transportation company and in California for the state’s geological survey. His work supported the concept that nature and industry can exist in harmony and stoked a “hunger for land” alongside the “desire to preserve it,” as the art historian Rachael Z. DeLue writes in the book accompanying Widening the Lens: Photography, Ecology, and the Contemporary Landscape, an exhibition at Carnegie Museum of Art through January 12, 2025.

Although Watkins and his brethren who established the foundations of landscape photography aren’t featured in Widening the Lens, their legacy looms over it nonetheless, as the exhibition pokes and prods at the ways our environment has both shaped and been shaped by the art form.

Many of the 19 featured artists contextualize the past, present, and future of landscape photography in ways that raise questions about what is and isn’t shown and the influence of those choices. In an era when nearly everyone can readily capture a landscape with ease—and as the natural world is threatened in ways scarcely imagined in the 19th century—the exhibition feels all the more urgent, says Dan Leers, the museum’s curator of photography.

“It was sad to feel like things hadn’t improved as much as we would’ve liked. But it’s also inspiring to think that these are questions people have been thinking and writing about for 60 years, and we’ll probably be engaging with for the next 60 years.”

–Dan Leers, curator of photography, Carnegie Museum of Art

Questions about climate change and environmental degradation have been at the forefront of Leers’ mind and many others’ in recent years. “These felt like issues that were too big to ignore,” he says. In considering how to approach them at the museum, he read Silent Spring, the 1962 book by Pittsburgh native Rachel Carson that ignited the environmental movement. He was struck by its continued relevance.

“It was sad to feel like things hadn’t improved as much as we would’ve liked,” Leers says. “But it’s also inspiring to think that these are questions people have been thinking and writing about for 60 years, and we’ll probably be engaging with for the next 60 years.”

Beyond the Flat Image

Widening the Lens flows through four themes, building a loose narrative that carries the history of landscape photography forward through work that often tangles with the legacy of the genre.

Visitors can encounter the exhibition from either end of the Heinz Galleries, but entering from the Scaife Lounge sets the stage with the section called “Archive,” which features work focused on the historical relationship between humans and the environment. The next gallery, “Remembering,” explores the ways photographers imbue nature with their own identities and memories. “Pathfinding” considers movement and migration across landscapes. Finally, “Horizon” looks to the future, wondering how our relationship to landscape may change in a time of environmental anxiety.

The works throughout the exhibition rarely look much like the photographs of Watkins and those who shaped our ideas of the genre, Leers notes. The landscapes on display include the blurred waistline of a man in the streets of Los Angeles; aerial views of the toll that uranium mining has taken on the Southwest; naked bodies embracing in the high desert; and images of Puerto Rico’s built environment.

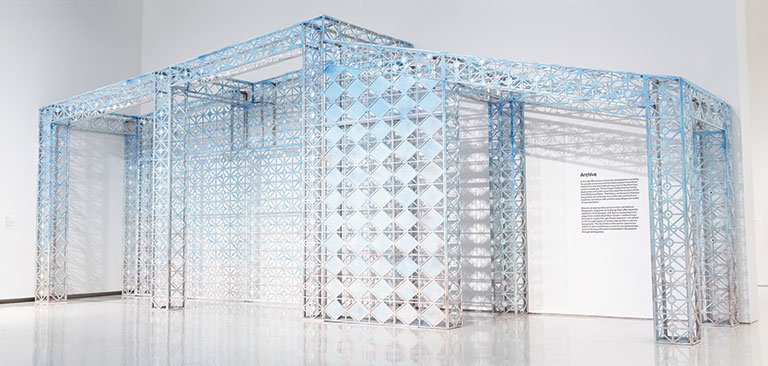

The latter appear in El Destino (Destination) by Edra Soto, which highlights the exhibition’s interest in expanding beyond traditional conceptions of photography. The work is a three-dimensional, room-sized structure modeled after Puerto Rican breeze-block architecture. Soto embedded nearly 200 viewfinders in the structure’s joints, inviting the audience to look closer to see photos she took during frequent visits to Cupey, the barrio where her mother was in hospice care before her passing.

Elsewhere in the exhibition, landscape photography takes the shape of tapestry, ceramic, video, and silk, pushing boundaries and encouraging introspection about where and how we see landscapes and feel an environmental presence.

“The way that everything is in conversation is a much-needed, expansive look at what photography is and what it can be—and also how it might be an agent of change,” says Melissa Catanese, a Pittsburgh-based artist whose piece Fever field was one of three commissioned for Widening the Lens, including Soto’s.

Catanese took many of the dozens of photos assembled in Fever field in Northern California during the spring of 2021, when the region was experiencing its driest season in more than a century and the pandemic was putting notions of loss front and center in the public consciousness. Its primary visual motif is the California poppy, a hardy flower that clusters together in mounds across the Bay Area, even during drought. Each photo in the towering 12-foot-by-16-foot collage is hung individually, unmatted and unframed, allowing gentle flutters and curling edges to bring Fever field to life. Given the fraught moment in which it was created, Catanese considers it “an elegy for collective grief, collective loss, personal loss, and political and ecological loss.”

“The way that everything is in conversation is a much-needed, expansive look at what photography is and what it can be—and also how it might be an agent of change.”

–Melissa Catanese, Pittsburgh-based artist

Fever field carries a message in its form as well, Catanese says, employing three different photographic processes as a comment on the piece’s ecological considerations. Most of the images are archival inkjet prints, a modern, nontoxic technology; several are cyanotype, a 19th-century process that uses little more than iron salts and sunlight; and some were made with lampblack ink, a historical medium that is “basically pure carbon,” Catanese says.

Among all those poppies, two of the photos show hands—one in an X-ray, as well as several hands that seem to be waving. They echo hands found in artworks throughout the exhibition, adding to a sense that every landscape has been shaped, in some way, by human touch.

“We wanted to think about the humans within the landscape itself. What kinds of histories are buried underneath? What kinds of stories are overlooked? And what kinds of perspectives have been ignored?”

–Keenan Saiz, Hillman Photography Initiative Project curatorial assistant, Carnegie Museum of Art

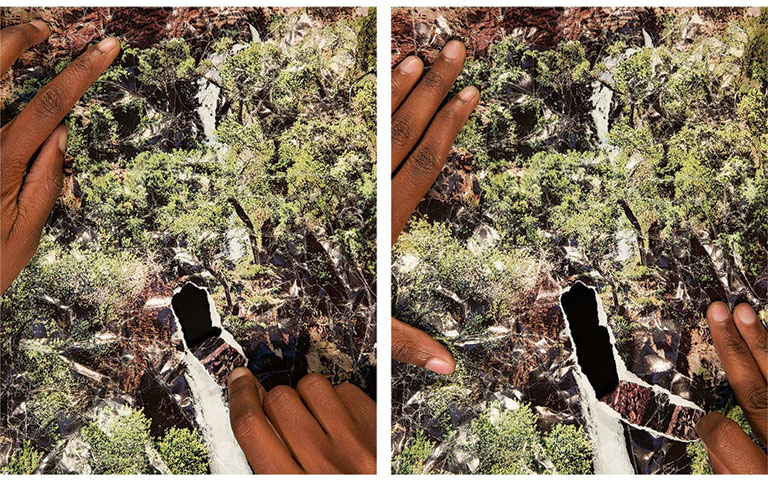

Dionne Lee’s Fire Bed shows her hand clearing a space for a campfire on the forest floor, contemplating the complicated relationship between Black Americans and the land. In the diptych Breaking the Fall, Lee’s hands tear the waterfall out of an image taken from a nature magazine. In Erin Jane Nelson’s The Tenderizer, the artist’s handprints are pressed into an embroidered quilt with images of the reflective waters of the Okefenokee Swamp near her home in Georgia. As with Fever field, all are in the “Remembering” section.

“We wanted to think about the humans within the landscape itself,” says Keenan Saiz, the museum’s Hillman Photography Initiative project curatorial assistant, who organized the exhibition with Leers—the fourth since the initiative began in 2013. “What kinds of histories are buried underneath? What kinds of stories are overlooked? And what kinds of perspectives have been ignored?”

Photographers like Watkins and his 20th-century successors, including Ansel Adams and Edward Weston, left humans out of their landscapes. But their absence can’t be ignored simply by keeping them outside of the frame. As Leers writes in the introduction to the exhibition’s book, “There are always many people in every landscape, even if we cannot see them.”

People vs. Land

Portions of the exhibition directly confront the tension that exists between people and the land, as in three large-format photos of the California desert by Victoria Sambunaris, found in the “Pathfinding” section. They show a railcar chugging across vast open space, and dirt bikers and dune buggies racing across sand dunes, leaving their imprint on landscapes that formed over millennia. Nearby, Chanell Stone, participating in her first major exhibition, traces the history of the Great Migration in a series of striking black-and-white self-portraits. Dressed in cotton, she wades into the waters of the Mississippi River and sinks into its muddy banks, a study in silt.

In works like these, the exhibition challenges inherited wisdom about the landscape and its “bucolic, romanticized nature,” Saiz says. In the process, it provokes new ways of thinking about the connections between photography, ecology, and ourselves.

“The photograph itself is a catalyst for curiosity,” Saiz notes. “As a document it has limitations, but it’s an avenue for people to see something beyond themselves—to see the world at a distance. That’s the power of a photograph.”

Widening the Lens raises important questions about how that power has been used through the decades, and what it might accomplish in those to come.

“The photograph itself is a catalyst for curiosity. As a document it has limitations, but it’s an avenue for people to see something beyond themselves—to see the world at a distance. That’s the power of a photograph.”

–Keenan Saiz

In addition to the exhibition and accompanying book, the museum explores those ideas in a six-episode podcast series, hosted by tennis champion and arts advocate Venus Williams, in conversation with several of the artists featured in the exhibition.

“Photography has helped shape our natural world,” Williams says in episode 1. “It has helped those in power expel peoples, extract resources, and claim space for development and industrialization. And in doing so, photography has helped lay the groundwork for some of our most daunting ecological crises today.”

But, she points out, that power can also be used to help us build a better way forward.

“Landscape photography has also created a critical record of what we have lost,” Williams says, “and maybe even asks us not to take for granted how fragile the environment is—and how powerful our actions really are.”

“Photography has helped shape our natural world. It has helped those in power expel peoples, extract resources, and claim space for development and industrialization. And in doing so, photography has helped lay the groundwork for some of our most daunting ecological crises today.”

–Venus Williams, in Episode 1 of the Widening the Lens podcast

If photographers like Watkins changed the way we understand landscapes and our relationship to them, the artists working today—and those of us capturing and sharing our own landscapes—can influence the environmental future, Leers and Saiz contend. But there is risk, Saiz notes, in the ubiquity of landscape photos and the ease with which they’re taken.

“Is what we all do with our phones another form of aestheticizing the land in a detached way?” he asks. “How much potential do we have with these tools to further understand the intricacies in the land, not only its history but its geology and the environmental knowledge it holds?”

Looking to the future, the exhibition’s final theme, “Horizon,” is embodied in the work of Lucy Raven, who shatters the traditional notion of a photograph. In Demolition of a Wall (Album 2), ultra-high-speed cameras and digital processing techniques allow her to visually map the extreme pressure sweeping across the landscape of Socorro, New Mexico, following explosions at a ballistics research lab. The piece is “an assault on the senses,” Saiz says, complete with room-rattling subwoofers that broadcast the concussive blasts and a set of metal bleachers from which visitors can take in the spectacle.

In Depositions, a more subtle but no less powerful series commissioned for the exhibition, Raven offers another way to consider the demolition of a wall and its impact on a landscape. She created a chamber filled with mounds of earth and lined with silk screens, then pumped in water from New York’s East River until the simulated dams inside the chamber breached and deposited their remnants on the silks. The result is four large-scale images formed by silt that somehow resemble mountains and deserts—land becoming landscape.

The series doesn’t implement light or lenses, Saiz says, but it still feels at home in an exhibition about landscape photography. It was inspired by the planned removal of four hydroelectric dams along the Klamath River at the California-Oregon border, and interrogates the role of industry in the American West that Watkins’ work once tacitly encouraged. The dams’ dismantling, which was completed in August, offers hope to threatened salmon species and the prospect of undoing ecological harm.

Like the landscapes that help define our relationship with the environment, Raven’s Depositions are fragile and malleable, Saiz points out. The silks that hold them are thin; particles are gradually flaking off. Museum conservators routinely visit the pieces, carefully collecting the dust that falls onto their wooden frames, sweeping away the remnants of earth and the memory of a dam that once was.

For Leers, Raven’s work is an opportunity to reflect on the profound impact we have on our surroundings—and the ways that landscape photography can make our influence clear to us.

“Even small actions we take reverberate,” Leers says. “They have an impact that moves through space and time.”

Major support for the exhibition is provided by the William Talbott Hillman Foundation and the Henry L. Hillman Foundation. Significant support is provided by The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts and the Henry Luce Foundation. Generous support is provided by Teiger Foundation. Widening the Lens: Photography, Ecology, and the Contemporary Landscape has been made possible in part by the National Endowment for the Arts.