Most collectors will claim art to be their passion. For Milton and Sheila Fine it truly was a love story. Theirs was a relationship that would last more than four decades, until Milton’s death in 2019. And from the very beginning, collecting art—not old masters or safe bets, but new works by rising stars and established living artists alike—was key to that partnership.

“It was part of our courtship,” says Sheila, still enthusiastic to the point of bubbling. “I found it exciting.”

Milton and Sheila collected art as an expression of love for artists and their works and for each other, but also as part of their love for the city of Pittsburgh. That’s because the Fine Collection wasn’t meant to stay in their home or scamper off to heirs as part of an estate, never to be troubled by the public eye. Their collection was for themselves, for a little while, and for Pittsburgh, forever. In a unique arrangement, they collected with Carnegie Museum of Art, and for the museum, too.

Now, four years after Milton’s death at age 92, the bulk of that collection has been fully accessioned into the collection of the museum the couple loved. And a new exhibition, The Milton and Sheila Fine Collection, open through March 17, 2024, celebrates the couple’s contribution with a show of a world-class assortment of works from the 1980s through the 2000s.

Photo: Sean Eaton

Photo: Sean Eaton“We are so fortunate, those of us who live in Pittsburgh, to have the art experience we have here—the Carnegie [Museum of Art], The Warhol, the Mattress Factory,” says Sheila. “And now we have the honor and the privilege to be able to make an imprint on that community.”

Pittsburgh Arts Philanthropists

The Fine name will be familiar to many who’ve worked in or simply enjoyed Pittsburgh’s ongoing artistic renaissance. Through their foundation, the Fines have given millions in funding to the region’s arts organizations. But all the while, there has been another string to their arts-philanthropy bow: a lower-profile mission to supplement Carnegie Museum of Art’s contemporary collection by purchasing complementary artworks that the Fines loved, and that would one day become part of the museum’s permanent collection for all to enjoy.

When Sheila met Milton more than four decades ago, their meeting coincided with Milton beginning to think more seriously about the artwork he’d begun collecting. Rather than just dabbling, he wanted to “get educated,” as Sheila says. Collecting quickly became a passion they shared as they grew closer. Part of that was the art itself, of course. And part of it was the excitement of entering the sometimes-hidden world of artists, curators, and collectors. To do that, the Fines joined forces with the museum’s curators, especially John Caldwell (curator, 1984-1989) and Richard Armstrong (curator and then director, 1992-2008).

“Milton was a very accomplished businessman and lawyer, but he still had a real shyness,” says Sheila of her late husband. “I’m very uninhibited, and I think I helped him to be more open. What I learned was that I’d look at a painting or a photograph and see things that perhaps you can’t talk about. Milt would often quote John Caldwell, who told us that when you’re looking at art, ‘when you feel a quiver in your knees—that’s the one you want.’”

It was no accident that Caldwell would play a significant role in Milton and Sheila’s relationship with art. In the mid-1980s, Milton was friends with museum director Jack Lane, who was on a mission to revitalize the waning influence of the Carnegie International as a nationally significant exhibition. Lane hired Caldwell as a contemporary art curator to do just that: seeking out and showing the brightest rising stars of the art world. Lane put Caldwell together with the Fines and a famous friendship was born. They traveled together, seeking out and meeting young artists both established and less known.

“The collection felt extremely personal. It was our courtship and our lives together—travel, with art in mind. But I love the fact that it’s going to the museum, who can manage it and use it to stimulate and educate people, and entertain them, in perpetuity.”

–Sheila Fine

“What gave Sheila and Milton joy was not just acquisition, but the joy of connecting,” says Eric Crosby, Henry J. Heinz II Director of Carnegie Museum of Art and Vice President of Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh. “Connecting with the museum’s curators and directors, and learning from them, and, of course, with artists.”

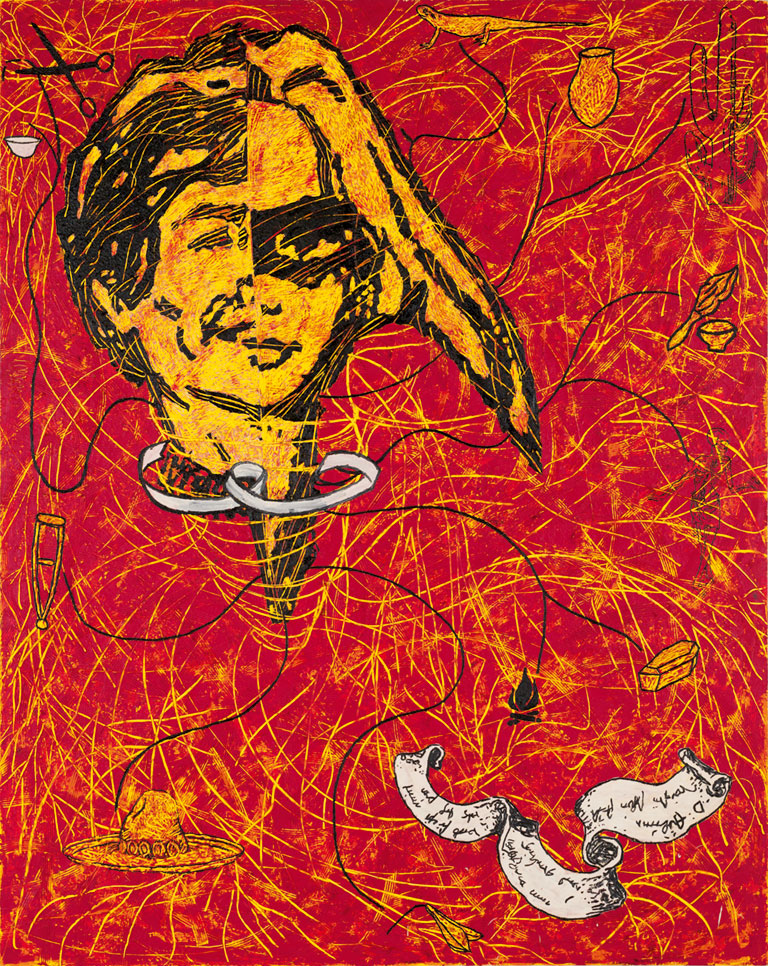

After Caldwell left the museum (he died soon after, in 1993), the Fines became even closer with his successor, Richard Armstrong, and continued traveling, learning about art and buying what excited them alongside the museum. More often than not, the “quiver in your knees” approach worked. Among the artists the Fines connected with—and whose work they have now gifted to the museum—are some of the biggest names in post-1980 art: Jeff Koons, Cindy Sherman, Christopher Wool, Kiki Smith, Mark Bradford.

The gift that has come from this time spent collecting is perfect for the museum because it was tailor-made for the institution. Consider Mark Bradford’s striking, layered painting Noah’s Third Day, one of the key works in the Fine Collection exhibition. The Fines encountered Bradford with the museum’s curators as they worked on the 2008 Carnegie International, just as he was becoming more well known—but still far from the renowned superstar the California-based artist is today. His piece, Help Us—lettering on the museum’s roof recalling the homemade signs of Hurricane Katrina victims—became one of the best-known works in that International, but the museum had yet to purchase any of his work at the time. The Fines did: They bought Noah’s Third Day in 2007, with one eye on its eventual accession into the museum’s permanent collection. It was a prescient purchase.

“The museum has no Mark Bradford in its collection,” says Crosby. “He was a really important artist in the 2008 International, but only since then has become a much more influential critical contemporary art voice. So now we have a work that will be regarded as one of the great masterworks of the collection, along with our lone de Kooning painting or our Monet Water Lilies.”

Besides Bradford, the Fine gift includes the museum’s first works by Jeff Koons, whose legendary status makes these sculptures and lithographs immediately key works in the museum’s collection of 1980s artists.

“Curators are always storytellers, regardless of what material they’re working with. Sometimes they’re tasked with telling an art-historical narrative, sometimes the story of a single artist’s career; in this case, our job is really to tell the story of this collection’s strength and development over time, and its impact on the museum as a gift. It’s just a different remit.“

–Eric Crosby, Henry J. Heinz II Director of Carnegie Museum of Art and Vice President of Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh

There is Bench and Table by sculptor Scott Burton, a key artist from the ’80s not previously represented in the museum collection (though known in Pittsburgh for public art contributions), and a photograph of Keith Haring by Robert Mapplethorpe. The names go on and on: Sol LeWitt, Gerhard Richter, John Baldessari—a veritable who’s who of 1980-2009 artists.

The Fine Collection strengthens the museum’s contemporary art collection in two different ways, as the museum’s current Richard Armstrong Curator of Contemporary Art Liz Park explains. It adds depth to the existing collection, while also filling in gaps, all the while remaining aligned with what the museum’s thinking has been for nearly 40 years.

“This isn’t something that formed in isolation,” says Park. “Because Milton Fine had a relationship with the museum going back to the 1980s and they collected alongside the museum, the artworks reflect past Internationals or other artistic programming, and it makes this gift really special—it can strengthen and complement the existing collection. As a contemporary art curator, I think about our collection as a living archive of past Internationals, and our ability to narrate that history of collecting and exhibition is made all the more possible by having the Fine gift integrated into the collection.”

A Personal Collection

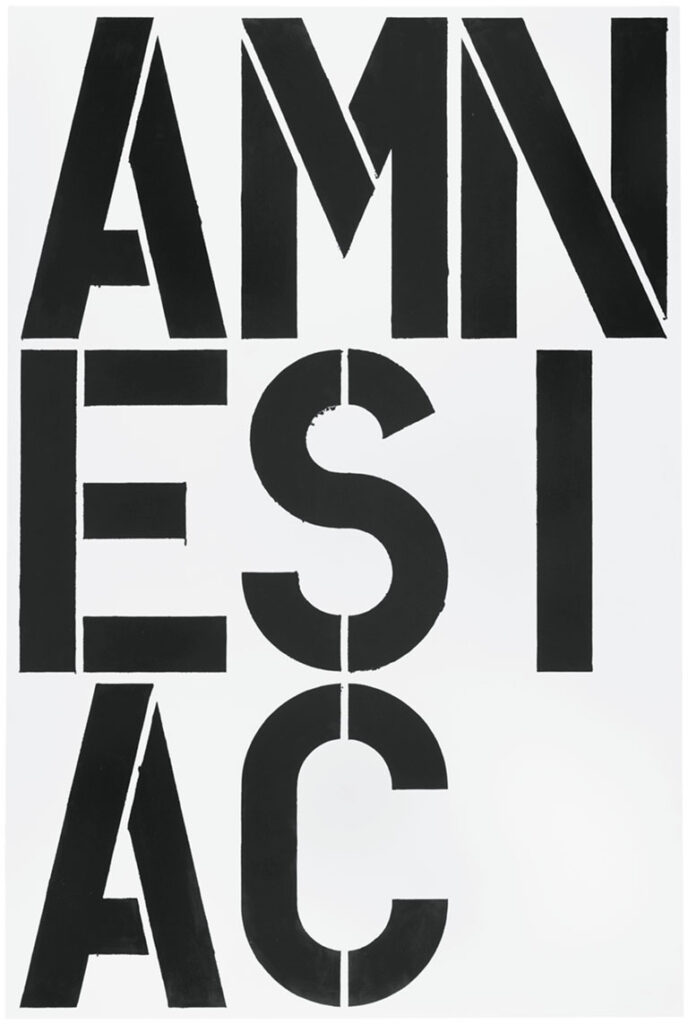

And yet, through their relationship with the museum and friendships with its curators and directors, Milton and Sheila were also collecting art as part of their personal life. They were works displayed for years in their home—Jeff Koons’ sculpture String of Puppies in the entrance hallway, and Christopher Wool’s untitled painting (Amnesiac) on the living room wall. Sheila points out that her grandchildren grew up with these artworks; a few select pieces followed the family from Pittsburgh to Florida and back.

This aspect of the Fine Collection presents a question for the exhibition: how to present something that is embedded within the museum’s practice, while also alluding to the personal side of its genesis. According to Cynthia Stucki, the museum’s curatorial assistant for contemporary art and photography, it’s something that has to be approached for visitors to understand the context of the exhibition.

“This is, for me, the first time I’ve directly worked on curating what was a private collection like this,” says Stucki. “We needed to bring some insight into this relationship between Milt and Sheila and the artwork, touch on what they were thinking or feeling. And that had to come largely through the exhibition text for each section of the exhibition.”

The exhibition is divided into sections based on the types of work the Fines focused on. A room for the masterworks, one for photography, one for minimalism. And there’s a room Stucki calls the Collector’s Salon—an accumulation of small paintings and other works on paper, as well as a table and chairs for visitors—which will give some insight into the Fines’ life with their artworks.

“That’s really a space where this idea of private and public spheres kind of blend together,” says Stucki. “Similarly, the Scott Burton Bench and Table [sculpture]—that’s something people can sit on, can interact with, and it speaks to that private-versus-public-sphere situation. You’re sitting on these chairs and looking at artwork that was once in their house, but now you’re in the gallery.”

“Curators are always storytellers,” says Crosby, “regardless of what material they’re working with. Sometimes they’re tasked with telling an art-historical narrative, sometimes the story of a single artist’s career; in this case, our job is really to tell the story of this collection’s strength and development over time, and its impact on the museum as a gift. It’s just a different remit.

“And in the case of the Fine Collection, there are so many through lines and points of entry into the collection that we want to surface for our visitors. We want to introduce them to Milton and Sheila, but also really foreground each of these artists—the exceptional quality of these works—and really treat the exhibition as an extension of our own collection galleries.”

The story being told here is, for Sheila, very simple: She and her husband loved art and wanted to share that passion, regardless of how close it had been to their personal lives.

“The collection felt extremely personal,” says Sheila. “It was our courtship and our lives together—travel, with art in mind. But I love the fact that it’s going to the museum, who can manage it and use it to stimulate and educate people, and entertain them, in perpetuity.”

For the Fines, philanthropy became a way of life—their foundation and its work in the arts and the Jewish community; the Fine Prize, which is given to an outstanding emerging artist from the Carnegie International; the endowment of the Milton Fine Curator position at The Andy Warhol Museum; and now the Fine Collection gift. To Sheila, it’s the only way to truly enjoy the bounty of life.

“I love chocolate,” she says, laughing to herself. “And I love a hot fudge sundae even more, because I can share it with someone. It tastes better that way. That’s just like philanthropy. Sharing things that you have, and that can give exponential pleasure to so many other people—that’s what excites me.”

Significant support for the exhibition is provided by The Fine Foundation and Women’s Committee, Carnegie Museum of Art. Generous support is provided by Sheila Reicher Fine Foundation, David J. Fine and The Fine Family Charitable Foundation, Carolyn Fine Friedman and The Fine Fund, and Sibyl Fine King and The Fine Family Foundation.

Additional support is provided by Nancy and Woody Ostrow, Jacqui and Jeffery L. Morby, Ritchie Battle, Juliet Lea H. Simonds, Susan and David A. Brownlee, Carnegie Mellon University, Ellen P. and Jack J. Kessler, janera solomon and Jeremy Resnik, Jane A. and Harry A. Thompson II, Brian Wongchaowart, Elizabeth Hurtt Branson and Douglas Branson, Ellen Still Brooks, Deborah G. Dick and Arthur H. Stroyd, Jr., Susan J. and Martin G. McGuinn, Silvia and Alexander C. Speyer, and Nancy D. Washington.