On a Saturday morning in May 2022, Nicole Heller and Bonnie McGill settled into Pavilion 10 at Mammoth Park in Mount Pleasant, Westmoreland County. They were giving a talk, “Climate Change in Your Backyard,” at the annual Sustainable Backyard Workshop.

Heller, associate curator of Anthropocene studies for Carnegie Museum of Natural History, describes a woman in her 60s or 70s who sat front and center and said this was the first time in all her years attending the event that someone was talking about climate change.

Halfway through the presentation, however, the woman put up her hands and said, “I’m doughnutting here.” Heller asked what that meant. “I want to go and get a doughnut right now,” the woman said, “because what you have said is so complicated, I can’t follow it anymore. You’re confusing me.”

This was exactly the kind of honest reaction that Heller and McGill say they needed to hear.

“[Doughnutting] was this perfect phrase to describe how I bet a lot of us feel when we get overwhelmed with the science,” Heller notes.

She and McGill, who at that time was a science communication fellow at the museum and now works for the American Farmland Trust, slowed down. They answered questions and explained some of the scientific complexity and, in the process, learned more about community concerns and interests. They left the workshop with more than they started with, including a note to bring doughnuts next time.

Creating CRSP

Heller and McGill were two core members of the museum’s initiative to have more productive conversations about climate change in rural communities. The Museum of Natural History wanted to build on the success of a previous project, the Climate and Urban Systems Partnership (CUSP), a multi-institute collaboration that focused on climate learning in Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, New York, and Washington, D.C., and concluded in 2018. The next logical question was about how to expand that framework into suburban and rural communities.

In 2019, the museum and the University of Pittsburgh were awarded grants from the National Science Foundation ($1.25 million and $794,923, respectively) toward that end. The idea behind the project, the Climate and Rural Systems Partnership (CRSP), was that museums have the scientific resources to understand climate change, but they weren’t connecting enough with rural audiences, for whom the topic can be socially complex.

Americans continue to have a rural-urban divide on the topic of climate change. Three out of every four Allegheny County residents (76 percent) believe that global warming is happening, according to the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication’s 2021 survey (the most recent data available). But in the more rural surrounding counties, the percentage dips to 63-66 percent. Responses as to whether global warming is caused by human activities follows a similar trend: 63 percent of Allegheny County residents compared to 46-53 percent of people in surrounding counties.

What, then, might bridge that gap? With the grants ending in 2024, CRSP’s partners have been reflecting on the project for answers.

For decades, climate change conversations have centered on the authority and communication methods of scientists, Heller says. There was an expectation that the data would show the urgency of the problem and spur people to action.

This has certainly been true for Heller, who has studied climate change science for decades. “Coming off a summer like we just had, with all the climate impacts all over the United States, I’m pretty desperate for action,” she says. But she admits to struggling at the start of CRSP in 2019. “I needed to learn that the project is really about respecting the pace of work of where your audience is.”

Part of that pace, she found, was the region’s long history with the fossil fuel industry. “Talking about climate change in this area can really be a red flag of like, ‘Wait a second, you’re talking about the end of fossil fuels—that’s a threat to my family or my area.’”

Taiji Nelson, CRSP’s initial program manager who is now a graduate student at the University of Washington, says it was important to choose partners that already had trusted relationships in rural communities. “The worst-case scenario was the museum going in and delivering information, telling people that we know best and that we want to change their lives for them without taking the time to ask, ‘What is it like here?’”

“Talking about climate change in this area can really be a red flag of like, ‘Wait a second, you’re talking about the end of fossil fuels—that’s a threat to my family or my area.’”

–Nicole Heller, associate curator of Anthropocene studies for Carnegie Museum of Natural History

To help bolster its community relationships, the CRSP program follows a kind of hub-and-spoke model. The museum and the University-of-Pittsburgh Center for Learning in Out-of-School Environments (UPCLOSE) developed communication strategies with regional hubs, which serve as convening points for their “spokes” (local organizations). Together they developed resources to make information accessible to people in diverse rural communities.

Both Powdermill Nature Reserve (the museum’s environmental field center in the Laurel Highlands) and the Mercer County Conservation District stood out for their expertise in addressing rural-related environmental problems and having established education programs that address them. They anchor, respectively, the Laurel Highlands hub and the hub that encompasses northwest Pennsylvania, named the Shenango Climate and Rural Environmental Studies Team (S-CREST).

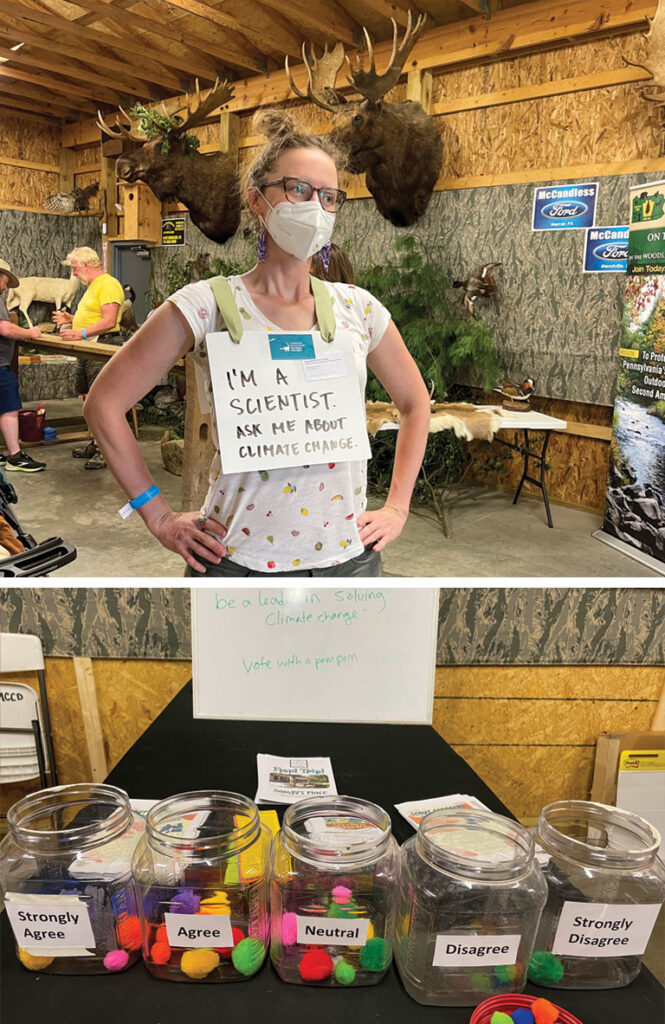

Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, CRSP’s first public-facing opportunity didn’t take place until Mercer County’s Great Stoneboro Fair in 2021. Their table was an activity called “Take a Stand.” Fairgoers could respond to the statement “I am concerned about climate change” by putting pompom balls in jars marked “strongly disagree,” “disagree,” “neutral,” “agree,” and “strongly agree.” The facilitators would then respond, “That’s interesting. What made you choose that one?”

“The good news about climate change is that it’s human-caused, because then that means it can be human-solved.”

–Bonnie McGill, Former Science communication fellow, Carnegie Museum of Natural History

Network members were pleased to see that climate change was a concern for an overwhelming majority of respondents, far more than they expected. Sixty-four percent were worried about climate change, with 19 percent in disagreement and 17 percent neutral. Participants wanted to talk about actions they could take, how scientists know climate change is human-caused, the political and economic challenges of the problem, and the seeming apathy at the larger social and global scales.

Laurie Giarratani, director of learning and community at the Museum of Natural History, says that some of the facilitators worried that fairgoers would be confrontational because of the politicized nature of the subject. It didn’t take long, though, to find out that, even when they disagreed, people were open to difficult conversations.

From what they experienced at the event, the team then “honed in on what kinds of things that people want to learn more about,” Giarratani says. From that, they could ask, “How can we shift the conversation from just general concerns about climate change to a more concrete understanding of what’s actionable?”

Heller says that one of the guiding principles of CRSP is keeping these conversations rooted in scientific evidence—always emphasizing that climate change is human-caused, for instance. But the other principles focus on the non-scientist or non-educator. According to a framework created by CRSP, a successful conversation about climate change and action is not a lecture; rather, it focuses on local conditions and lived experience, allows for personal feelings, and connects to large socio-ecological systems.

Conversations should also focus on creating hope through solutions that include opportunities for individual involvement, from home improvements to voting. “The good news about climate change is that it’s human-caused, because then that means it can be human-solved,” McGill says.

Also good news: Not believing in climate change or its cause does not preclude belief in taking related action. In the rural counties surrounding Allegheny, between 73-75 percent believe that there should be funding for researching renewable energy sources (in Allegheny County, 79 percent.)

There are also economic reasons for seeking climate solutions. One resource created by McGill and agricultural professionals was a pamphlet to be distributed to local farmers that includes pragmatic information about farming practices that are both more environmentally sustainable and more productive, as well as funding resources and networking opportunities.

The brochure was one of several resources made by CRSP partners.

Alexis Boytim, CRSP’s senior program manager at the museum, says there were network members in the Laurel Highlands hub who wanted to talk about climate change but didn’t feel confident enough in their knowledge of the subject or in how to relay that knowledge.

So, they created a “conversation guide,” which includes how to focus discussions (e.g., taking action); six climate actions people can start doing immediately (eating a more plant-rich diet); climate change basics that address common questions (isn’t climate change a natural occurrence?); and conversation starters (asking people whether they’ve noticed the increase of solar panels in Pennsylvania).

Similar to network members, S-CREST coordinator Kelcy Marini found that many people believe that climate change is happening, “but they just don’t have the resources to learn more about it or don’t know where to start.”

Toward that end, Marini worked with Mary Ann Steiner, an UPCLOSE researcher, and network members to create nearly 100 climate cards that offer quick facts about climate solutions, such as green infrastructure for stormwater runoff, cover crops, and harnessing solar power. They tested the cards at nine public programs and community festivals.

It’s all part of a larger conversation about the changing roles of museums and large institutions, Heller says, adding that an overall trend for museums “is to really be a lot more participatory, a lot less one-way communication, and more bidirectional.”

Leading By Learning

Giarratani thinks the challenge with this project is to lead in a way that’s supportive and strengthens “our collective work.” Network members seem to want support from larger institutions, particularly when the hubs bring people together to share stories of success and learn from failures. “What people don’t have is somebody else to say, ‘Oh, hey, this is what we tried. And this is what was hard about it. This is what we learned,’” she notes.

“Just the fact that we’re having these conversations means we’re being successful.”

–Kelcy Marini, S-CREST coordinator

The museum can offer scientific support to smaller community groups and also bring rural perspectives into the museum, Heller says, “so visitors can experience the diverse people taking action in our community to make western Pennsylvania a more sustainable and equitable and biodiverse place.”

For people like Marini, who was born, raised, and lives in Mercer County, “just the fact that we’re having these conversations means we’re being successful.” Nelson, who also grew up in rural Pennsylvania, attributes that success to focusing on partnerships with trusted members of the community.

As conversations about climate change become normalized, CRSP leaders say the next step is direct action, which can include anything from individuals eating less meat to a community organizing a solar cooperative. CRSP helped the museum learn what people and organizations across western Pennsylvania are doing to have a larger impact in their communities, and how the museum can support that work.

“Knowing what we know from this project, how can [the museum] both take stronger climate actions as an institution and support others in doing so across the region?” Boytim asks. “That is a space the museum is committed to growing into, and that would also be a success.”

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant #1906774. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Receive more stories in your email

Sign up