For years, Carnegie Museum of Art associate registrar Elizabeth Tufts-Brown had heard about “little black books” kept by Gordon Bailey Washburn during his tenure as the museum’s director more than a half-century ago. But nobody knew where they were or what, exactly, was in them.

Some of the museum’s most iconic works of modern and contemporary art—Henry Moore’s Reclining Figure and Alberto Giacometti’s Walking Man I—were acquired by Washburn, who served as director from 1950 to 1962. During that time, he also curated five Carnegie Internationals, and is credited with revitalizing the International as a major worldwide art exhibition.

“The letters back and forth between Washburn and the museum staff were written every few days at the most, and sometimes every day,” says Tufts-Brown. “In them, there is much talk of the little black books—updating them, sending whole books or just pages to Washburn at whatever hotel in whatever country he was staying in.”

His experiences of scouring studios and workshops and galleries across Europe, finding artists to exhibit in Pittsburgh, had been well documented in letters, memos, ship manifests, and other documents that reside in the museum’s archives. But the little black books appeared to have fallen into a black hole. Tufts-Brown couldn’t find any evidence of them.

It was a mystery.

Then one morning in early February 2017, Ingrid Schaffner, curator of the Carnegie International, 57th Edition, 2018, got a phone call from Paris. The woman on the line said her name was Frances Washburn.

Schaffner described what happened next to an audience at the Carnegie Mellon University Libraries in 2018.

“‘My father used to be the director at your art museum,’” Schaffner recalled her saying. “‘I live in a tiny little apartment in Paris and I’m trying to get rid of some things, and I have these little black books.’”

“She literally said, ‘these little black books’—and I’m like: ‘Hold the line!’” Schaffner recounted how she ran down the hall, got Tufts-Brown, and both listened as the woman in Paris told them the museum was “welcome to have them.”

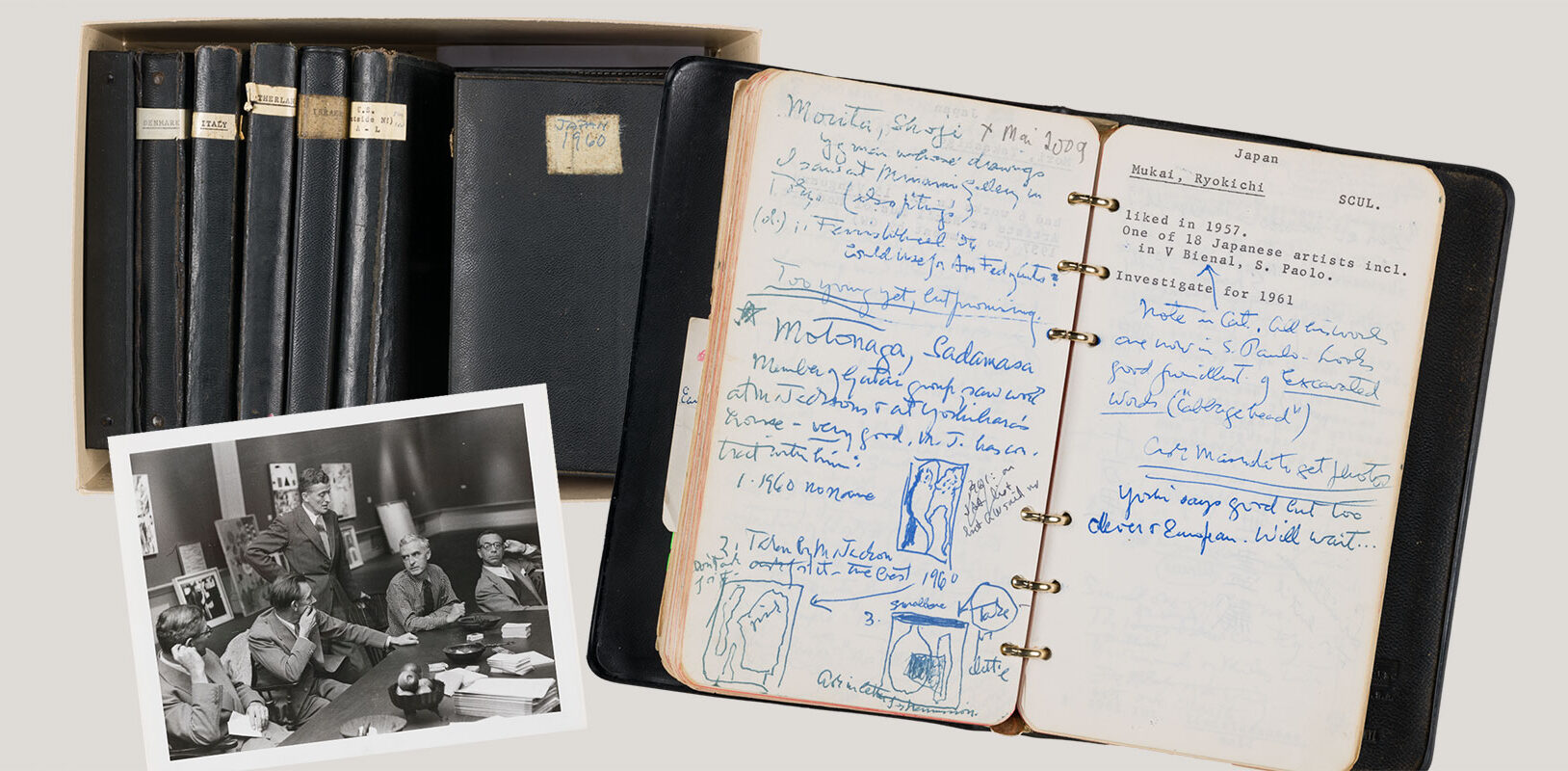

There were a total of 23 binders in all, each roughly about the size of a small paperback. (Carnegie Museums later donated nine of them to the Asia Society in New York because they pertained to Washburn’s work there after he left.)

“If we lost our phone we’d be terribly upset; if he lost this, he’d be really upset.”

–Elizabeth Tufts-Brown, Associate Registrar At Carnegie Museum Of Art

As luck would have it, Akemi May, the museum’s associate curator of works on paper, was scheduled to fly to Paris the following week. Carnegie Museum of Art was lending one of its Pissarros to an exhibition at the Musée Marmottan Monet, and May was delivering the painting and overseeing its installation. So she agreed to retrieve the black books.

Once the Pissarro was in place, May took the Metro from the 16th district across town to the Place de la République. Frances Washburn’s apartment was on the fourth floor. May took the stairs.

A tall, thin woman with short gray hair and glasses answered the door.

“She was very lovely,” May recalls. They chatted for more than an hour.

The black books were full of typewritten pages detailing all the resources Washburn would require in each country: hotels, restaurants, galleries, shipping agents, lists of artists.

“We talked about her father and his time at the museum,” says May. “She had kept these things in deep storage. She hadn’t looked at them in quite some time. She realized she didn’t have much use for them … but since they related to his work for this institution, she thought we should have them.”

Tufts-Brown is still studying the books, which are a combination of travel planner and Rolodex. They are the backbone of Washburn’s European trips: where he stayed and ate, who he likely met with, all annotated in Washburn’s scrawl. Some pages have his pencil sketches of artworks he saw. They are analogous to a modern traveler’s smartphone. Tufts-Brown says, “If we lost our phone we’d be terribly upset; if he lost this, he’d be really upset.”

Some include lists of artists or artworks—with letter grades next to them. One piece in the museum’s current collection (Tufts-Brown was hesitant to name the work) received a D. “It’s very harsh,” she says.

While the books—at first glance—can seem bare-bones, they can also collate with other archive documents in fascinating ways.

The success of Washburn’s Internationals wasn’t simply the quality of the artwork he solicited; it was also making sure there were buyers. “At that time, the works were sold right out of the show, and we had to keep track of the buyers and where to ship everything after the show closed,” notes Tufts-Brown. Washburn was also cultivating potential patrons on his trips to Europe.

As Tufts-Brown works her way through the details in the books, she says they offer other pieces to fit into the puzzle of connections between curator, artists, and patrons—of how Washburn worked, how the Internationals came together, and why the current collection came to be what it is.