Before Facebook and Twitter, before the Kardashians became famous for being famous, before influencers hawked makeup and clothes, Andy Warhol had his own social network.

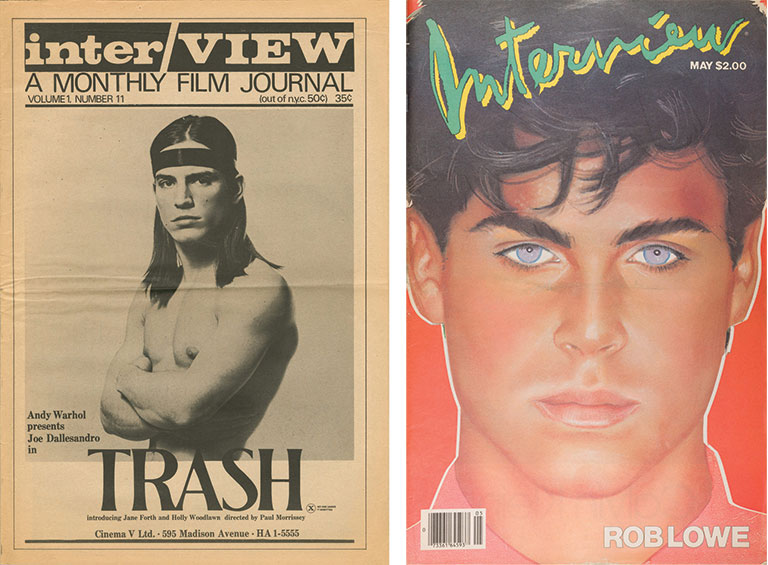

In 1969, the Pop art superstar created Interview, a magazine showcasing the cool and glamorous celebrities floating in and out of his studio.

As though he could see decades into the future, he also launched three reality TV shows—Fashion, Andy Warhol’s TV, and Andy Warhol’s Fifteen Minutes. His famous pals—Debbie Harry, Liza Minnelli, John Waters, Bianca Jagger, Halston, and so on—did quirky bits for the TV camera and interviewed each other for his magazine. They also would pose for his famous silkscreen portraits.

Now the public can explore how Warhol became a savvy influencer and social media star before his time in the new exhibition, Andy Warhol’s Social Network: ‘Interview,’ Television and Portraits, which is on view at The Andy Warhol Museum until February 20, 2023.

Jessica Beck, the former chief curator at The Warhol, says the artist’s social network of the 1970s and ’80s portended what’s happening today. “It shows you how Warhol was really tapping into a slice of youth culture. … It’s about being prescient about technology and how advertising and the commerce world and our personal lives start to blend and mix.”

In Season 1, Episode 16 of Andy Warhol’s TV, Bianca Jagger interviews Steven Spielberg about the making of the movie E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial. Spielberg is sitting on the bed of a hotel room, giving the viewer the feeling of eavesdropping. “It’s also creating this false sense of intimacy. It’s almost like you’re sitting down as a third person at lunch,” Beck says. “And that was what social media was offering us in the beginning, the proximity to celebrity culture.”

During this TV clip, Warhol sits in the room, asking a few questions but mostly listening to Spielberg talk. “Warhol’s this constant listener,” says Tyler Shine, former assistant curator at The Warhol. “He has his ears to the ground for everything that’s new, cool, hip, and cutting-edge.”

Just as Warhol sidestepped the studio system to showcase young up-and-comers on his new media channels, some of today’s modern stars got around the normal gatekeepers and found their audience on social media. For example, a teenage Justin Bieber started uploading his music videos to YouTube and caught the attention of music producer Scooter Braun in 2007. When record labels initially passed on Bieber, Braun helped Bieber develop a mega-following on YouTube, catapulting him to his place as a teen idol.

“Warhol’s this constant listener. He has his ears to the ground for everything that’s new, cool, hip, and cutting-edge.”

– Tyler Shine, Former Assistant Curator At The Warhol

That feeling of intimacy created by Warhol in Andy Warhol’s TV was echoed in the early days of social media, Beck adds, before social media became commercialized with big brands sponsoring the “influencers” of the day.

“Layering Of People”

Warhol’s beautiful friends bounced among his three social platforms—his television shows, his magazine, and his portraits. Consider Debbie Harry, the lead singer of the new wave band Blondie. The blond rocker was his muse in the ’70s, the way Edie Sedgwick was in the ’60s. In the first episode of Andy Warhol’s TV, which aired on Madison Square Garden Network, Warhol stands behind a Polaroid camera and snaps photos of Harry dressed in a black mini dress. He stops once to smooth her hair. Then the camera zooms in on the finished product of that photo shoot—a silkscreen portrait of Harry’s face, with turquoise eyeshadow and bright red, heart-shaped lips—which is on display as part of Andy Warhol’s Social Network. She’s also featured on the cover of Interview magazine and often narrates his TV shows.

“Debbie Harry is the muse of this period, the ’70s, but we have other figures like Mick Jagger who appear over and over, and who connected Warhol to the ’60s,” Shine says. “That overlaps with other people—fashion designers and models who became celebrities in their own right. It’s this constant building and layering of people by Warhol.”

In video clips of Andy Warhol’s TV playing as part of the exhibition, the artist speaks in his droll, deadpan voice about all the parties and clubs and new restaurants he visits constantly. He might give the impression of an idle socialite who flits about. But he was always working, filming while interviewing celebrities, and signing deals for commissioned portraits, the moneymakers of this era.

Warhol launched Interview magazine a year after the trauma that nearly killed him. On June 3, 1968, Valerie Solanas, a troubled writer who appeared in one of his films, entered his studio and shot him. Warhol was reportedly declared dead when he arrived at the hospital, but was revived after five hours of surgery. He spent two months in the hospital recuperating and had to wear a surgical corset the rest of his life. Having moved out of his famed studio the Silver Factory, he reconfigured his new studio, hiring business-savvy young associates such as Bob Colacello and Vincent Fremont. He ventured into new mediums, continuing his pattern of offending the art establishment along the way.

Interview Takes Shape

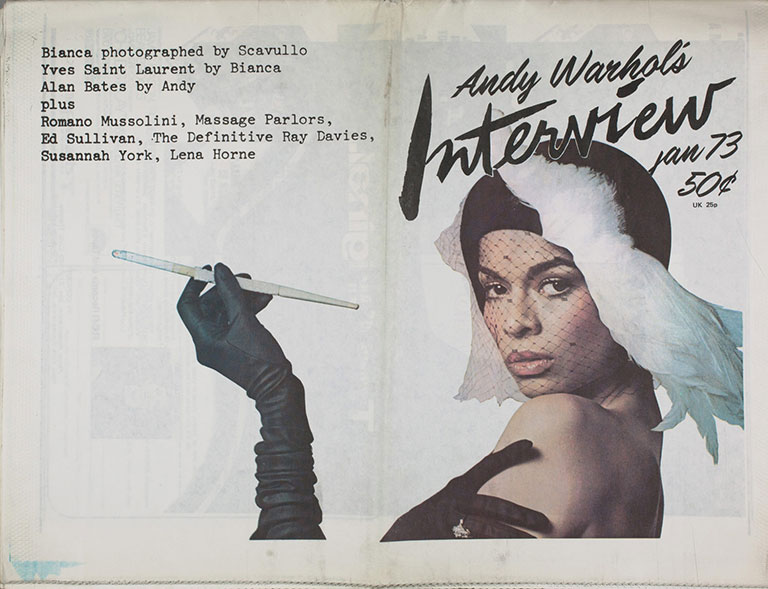

Interview was Warhol’s longest-running venture, and for the first time The Warhol exhibition shows 204 issues of the magazine dating from 1969 to 1987, the year of Warhol’s death, with only one missing. The last issue was in memoriam to Warhol. (The magazine was relaunched under new owners shortly after his death and is still published today.)

Right: Interview – Vol. 14, no. 5 (May 1984) [Rob Lowe Cover], 1984, The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Gift of Mikki Thomas Brown, Artwork: © 2022 The Estate of Richard Bernstein / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, Magazine: © Interview Magazine

Andy Warhol’s Social Network shows the stylistic evolution of the magazine. It starts as a black-and-white publication, conceived as a cross between Rolling Stone and Screw magazines. One early issue has a photo of Raquel Welch in a bikini, and subsequent issues have nude centerfolds. “It had this underground-film influence with pornographic undertones,” Beck says. In the early years, there was no clear format to the magazine.

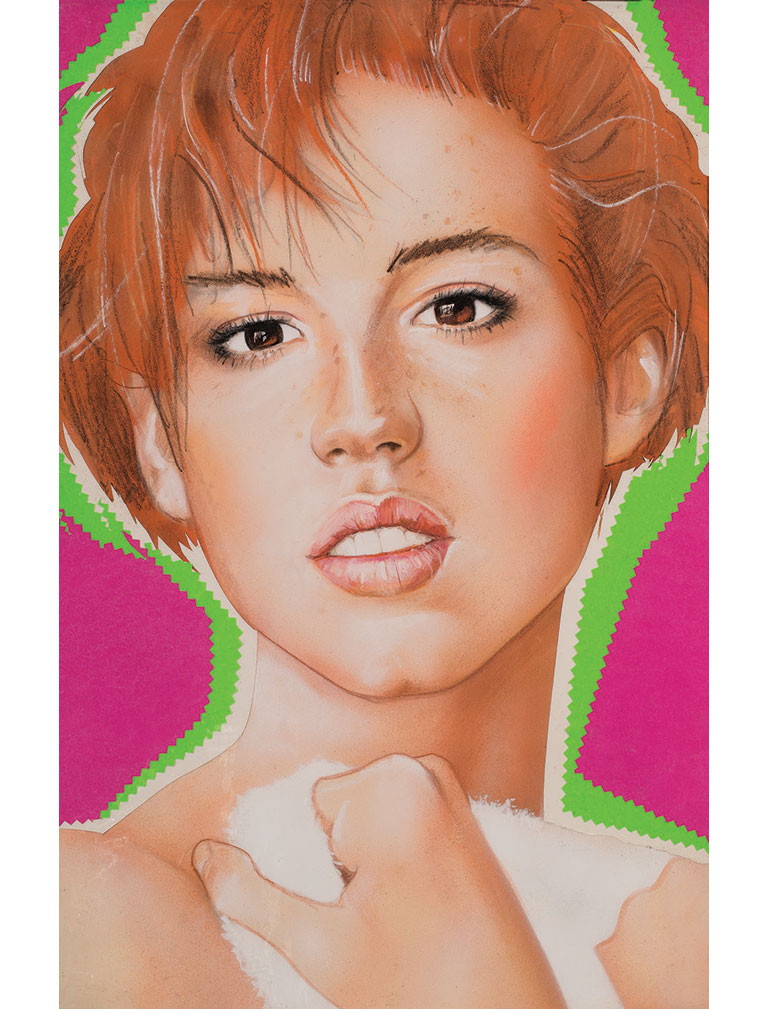

But in the ’70s, Interview became a highly polished and stylized magazine with iconic cover portraits created by Richard Bernstein, a forgotten superstar artist pulled back into the spotlight by the exhibition. His luminous and brightly colored covers added extra shine to celebrities including Grace Slick, Rob Lowe, and Twiggy. But because it was Warhol’s name and not Bernstein’s on the cover, most people had no idea that Bernstein created the cover art.

“Richard was definitely eclipsed by Warhol,” says Beck, who addresses that slight by giving Bernstein his own gallery in the exhibition.

Warhol met Bernstein when he attended the popular artist’s solo exhibition in New York City in 1965. “They hit it off,” says Rory S. Trifon, president of The Estate of Richard Bernstein and nephew of the late artist. Warhol and Bernstein even hung out with the same crowd in New York.

When Warhol approached Bernstein about making cover portraits, Bernstein had been creating colorful Pop Art photos of pills—a reference to the drug-filled club era.

“Stop painting the pills and start doing the portraits because that’s what pays the rent,’’ Trifon quoted Warhol as telling Bernstein.

Making the cover portraits was a complicated process. Some of the most famous photographers of the era, such as Francisco Scavullo, would take black-and-white photos and give Bernstein the prints, which he would crop and then blow up. Then Bernstein would paint, airbrush, and pencil in beautiful hues so the dewy faces would pop from the newsstands.

“Richard only selected portraits of people he knew really well,” Trifon says. “Just like Andy, he had this big social coterie of people that would hang out at Max’s Kansas City or Studio 54 or at the Chelsea Hotel, where Richard lived. He put a lot of love into them.”

In the forward to Megastar, a compilation of Bernstein’s Interview covers, Paloma Picasso, Pablo’s daughter, wrote: “Richard Bernstein portrays stars. He celebrates their faces, he gives them larger-than-fiction size. He puts wit into the beauties, fantasy into the rich, depth into the glamorous and adds instant patina to newcomers.”

In Andy Warhol’s Social Network, Bernstein’s portraits are hung on turquoise and pink wallpaper made for the exhibition—fashioned from a profile portrait Bernstein did of Warhol.

Escapist Media

The magazine covers, like Andy Warhol’s TV, offered a fun distraction during a time of nationwide tumult, with the country roiling from the Vietnam War and the energy crisis. “Richard made these celebrities larger than life, more ethereal,” Trifon says, “and I think people were drawn to that as a form of escapism.”

Bernstein also helped the magazine get national distribution and land big advertisers such as jewelry and perfume companies, in the same way the final iteration of his TV show, Andy Warhol’s Fifteen Minutes, was broadcast on MTV.

But the big moneymaker through this phase of Warhol’s career were his commissioned portraits, which could bring in $25,000 or more a piece. In the early days of his new media ventures, Warhol used portrait sales as the main funding source of his multimedia interests.

One wall of the exhibition shows Warhol’s evolution in style through a series of his silkscreen portraits. While the early works incorporate shadows and realism, later works were carefully airbrushed, with a flattened style that included faces free of imperfections. While those portraits are heralded today, they were criticized by the art world at the time. One critic even called him a “court jester,” implying that Warhol was pandering to celebrities with flattery.

With Warhol’s love of celebrity and penchant for putting his network of celebrity friends on display, it begs the question: What would Warhol be doing today?

“I think Warhol would be way beyond Instagram, TikTok,” Beck says. “I think at this point, Warhol would be working with AI (artificial intelligence) developers. He would be onto the next thing because he was always surrounded by young people.”

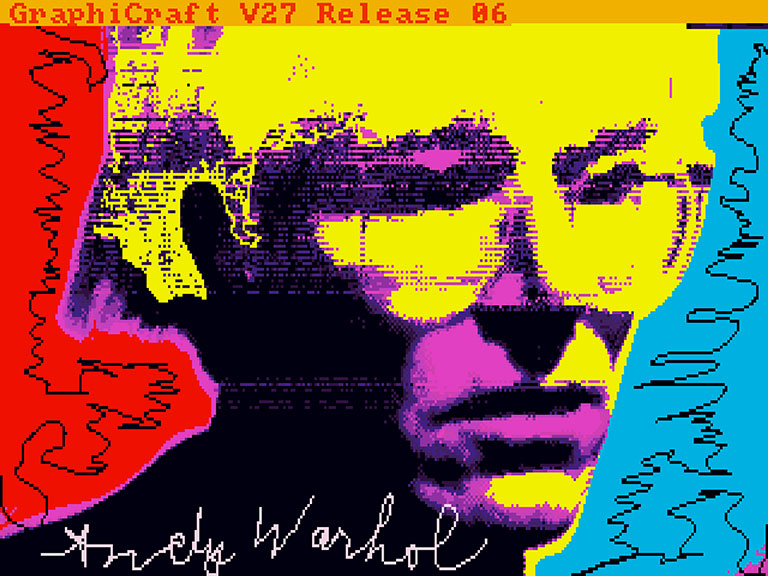

Even in the ’80s, when he met Apple co-founder Steve Jobs at the birthday of Sean Lennon (son of John Lennon) installing one of his brand new Apple computers, Warhol commented in his diaries. Beck says he wondered who this young kid was who knew so much about computers.

“I think Warhol would be way beyond Instagram, TikTok. I think at this point, Warhol would be working with AI (artificial intelligence) developers. He would be onto the next thing because he was always surrounded by young people.”

– Jessica Beck, Former Chief Curator At The Warhol

“The next thing you know, Warhol struck a deal with Commodore computer,” Beck says. He created a computer-generated portrait of Debbie Harry as part of his endorsement deal.

“I think that was one of his gifts—that he knew how to work with younger people and younger ideas, but he always maintained a specific aesthetic or style- or image-consciousness around the work and his own presentation,” Beck says.

Beck notes that people who came to the opening of the exhibition were thrilled by the nostalgia of seeing Farrah Fawcett on an Interview magazine cover or Debbie Harry and Ali McGraw on Andy Warhol’s TV in the ‘70s and ‘80s. And yet, there’s something current about it all, as though it could have all been created today.

“It’s really fun visiting that period,” Beck says. “But people are struck by how vibrant it feels. It’s not like looking back at something that feels dusty or dated. It still feels very much vibrant and alive.”

Andy Warhol’s Social Network: ‘Interview,’ Television and Portraits is generously supported by The Fine Foundation and is financed in part by a grant from the U.S. Department of the Treasury, under the administration of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Pennsylvania Department of Community and Economic Development.