You May Also Like

Opening up the World for Others ‘We Do Still Exist, and We’re Thriving.’ Creative ConnectionsFive miles separate Carnegie Science Center from Perry Traditional Academy on the North Side, though in the past they’ve seemed to exist in separate worlds.

Perry teachers say that many of their students have never visited the Science Center. North Side families have a lot of other competing opportunities for how to spend their time, they say, and Perry staff don’t necessarily have the resources to figure out how to tap into all that the Science Center has to offer.

But that’s changing. Rather than rely on Perry students to come to the Science Center, the Science Center is going to Perry.

“For so long, as museums, we’ve seen ourselves as the people holding the information that we then disseminate to the schools or visitors coming to see us,” says Shannon Gaussa, workforce and community readiness program coordinator at the Science Center. “Now museums are rethinking all of this. We see that our communities have different needs, they have different knowledge bases. They have so many strengths that we can build on.”

An ambitious effort led by educational advocate A+ Schools is working to transform Perry into one of the city’s top high schools by partnering with community organizations like the Science Center. The effort was born out of the One Northside initiative, which is supported by the Buhl Foundation and being guided by a steering committee of partners from Pittsburgh Public Schools, the Pittsburgh Federation of Teachers, and the Pittsburgh Promise.

“For so long, as museums, we’ve seen ourselves as the people holding the information that we then disseminate to the schools or visitors coming to see us. Now museums are rethinking all of this. We see that our communities have different needs, they have different knowledge bases. They have so many strengths that we can build on.”

–Shannon Gaussa, Workforce And Community Readiness Program Coordinator At Carnegie Science Center

The Science Center is one of four North Side community partners that have been meeting biweekly with Perry staff over the past year to figure out how best to incorporate STEAM—Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts, and Math—learning into lessons for 9th and 10th grade students at Perry, while introducing potential career paths to students who may have never considered them. Dozens more organizations partner with Perry to offer mentoring and other educational programs.

The path that this partnership has taken has been neither straight nor easy. It involves years of preparation and planning sessions with at least three dozen people, not to mention plenty of surprises and setbacks, including keeping the ball rolling through a pandemic. But it is an initiative that Perry teachers, Science Center educators, and other partner institutions hope will bring them, inch by inch, to the peak of academic success.

“We’re trying to keep it positive and make sure the kids are living up to the best of their abilities and see the potential that they have,” says Ashley Simpson, a Perry Biology teacher, one of 18 Perry educators involved. “Sometimes that’s a struggle, but you try to get the kids to see that they can succeed and you try to increase their confidence and that growth mindset in order to get to where they need to be.”

Partnering On Steam

Teacher participation in the Perry Initiative is voluntary. Simpson jumped at the opportunity.

She joined planning meetings at the end of the last school year and worked with the Manchester Craftsmen’s Guild on a weeklong mini-unit taught in September. Using detailed templates custom-designed by a digital teaching artist at Manchester, students created their own original biomes and a creature suited to living there. The unit concluded with a trip to the Guild’s offices, where students used Adobe software to create playing cards of their creatures.

Simpson doesn’t expect it will inspire all her students to go into gaming design; she just wants to get the kids engaged in the outcomes of STEAM learning, such as the ability to problem-solve and work in teams.

Educators at Carnegie Science Center’s Center for STEM Education and Career Development (STEM means Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math) say they’re hoping to help students build lifelong problem-solving skills and curiosity.

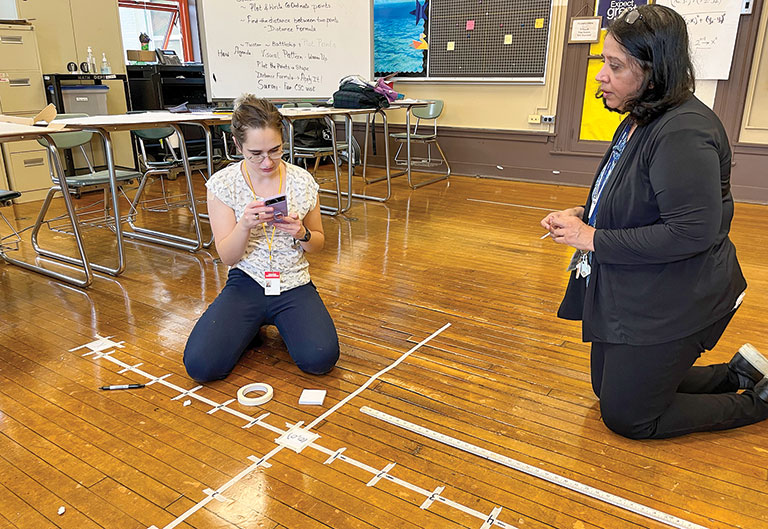

coordinates on the floor for a STEM lesson.

“This partnership is a success if we see that they’re grasping STEM skills that can be applied to all areas of life—practicing failing and trying again, getting curious,” says Gaussa, who spearheaded the partnership with Perry. “We’re also focused on developing an awareness of the many STEM careers out there and the diverse paths to getting into those careers.”

STEM education is an interdisciplinary teaching philosophy heavily focused on real-world problem-solving. It’s an approach that has been promoted by educational experts to prepare younger generations for careers in an increasingly complicated and technical world. Informal science education like that offered at the Science Center has an important role to play, according to the National Research Council.

STEM concepts have long been part of the Science Center’s programming. Science Center educators develop resources for classroom teachers and host early childhood education classes on-site, public workshops, summer camp programming, and community events. Their “spiraled approach” is to instill basic STEM concepts in children before they reach kindergarten, and then build on those experiences as they get older.

But STEM education at the Science Center also happens out in the community, such as the partnership with Perry.

For the past few years, Perry has been working with A+ Schools on a multi-pronged school improvement program. The initiative includes partnerships with North Side organizations on STEAM education that could introduce students to potential career paths. The COVID-19 pandemic and leadership changes at Perry slowed progress, but by fall 2021, the program was finally ready to bring these neighborhood organizations on board.

“Once you put students in this hands-on and real-world experience, they are fully engaged,” says Amie White, chief operating officer of A+ Schools. “That’s what this is all about. Not just trying to box students into one way of learning, or one way of exploring what career options they want to have.”

Building Trust

Building relationships within communities requires trust, and trust doesn’t come quickly.

February 2022 was the first time the Science Center could engage with Perry students in person. That’s when the plan on paper met the realities of the classroom.

Gaussa and a Science Center colleague planned a weeklong introduction to STEM for ninth grade students. Attendance and engagement were lower than they expected; only 25 of the 40 students expected showed up, and then just three students overall knew what the STEM acronym meant. After a few days, Gaussa pivoted to focusing on getting to know the students more personally.

The school facility itself, an imposing century-old Classical Revival style building, is well kept and the classrooms are outfitted with large touch-screen monitors, lab equipment, and other technology useful for STEM lessons. The teachers and tools were there, but challenges remained.

All of Perry’s nearly 400 students qualify for free lunch, a measure of poverty, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. And Pennsylvania Department of Education data shows that Perry’s performance measures are below other high schools in Pittsburgh and across the state. In the 2020-21 academic year, just 6.7 percent of students were considered proficient or advanced in mathematics, compared to 37.3 percent statewide. Only 27.7 percent of Perry students attended classes regularly. The statewide average is 85.8 percent.

“Once you put students in this hands-on and real-world experience, they are fully engaged. That’s what this is all about. Not just trying to box students into one way of learning, or one way of exploring what career options they want to have.”

–Amie White, Chief Operating Officer Of A+ Schools

On a typical day, Perry geometry teacher Kay Ramgopal says she’ll get two-thirds of students on her roster. And those who do attend regularly are often exhausted due to responsibilities outside of school, such as holding down a night job or caring for siblings, adding to the challenges of focusing on academics during the day.

“I look at them and say, ‘How do you do it?’” Ramgopal marvels.

Supporting and engaging with teachers like Ramgopal will be key to meeting these challenges, Gaussa says.

“One of the big strengths I see in the Perry community is the teachers, the relationships they have with their students, and the trust that they have,” says Gaussa.

Instead of offering prepackaged lessons, the Science Center and other community partners are working directly with teachers to custom-fit STEM lessons to the specific circumstances of each classroom.

Ramgopal first met Gaussa and Luci Finucan, a STEM educator at the Science Center, in July to workshop ideas for lessons.

Cartesian coordinates—a grid of two intersecting lines, with a horizontal x-axis and vertical y-axis—is an essential concept that Ramgopal needs to teach to her 10th- grade geometry students. Finucan had an idea to teach the concept through games of Twister and Battleship. Ramgopal agreed to go forward with it.

Ramgopal recalls Finucan’s excitement about working with coordinates in a new way. “That was when we were looking at my syllabus to see where everything would fit in.”

Having received the thumbs up from Ramgopal, Finucan and Gaussa then fleshed out the lesson, hammering out specifics with Ramgopal over Zoom a week before. By late September, they were ready.

Coordinated Fun

The day of the lesson was unseasonably warm, in the mid-80s, so the windows were open. As students filed in for their final block of the day, they sat along the perimeter in search of a cool breeze.

Eight students were present when class began—less than half of those on the roster. Ramgopal says the composition of the class changes regularly. She calls home for students who she hasn’t seen in a while.

These sophomores are of the same cohort that Science Center staff visited back in February when they were ninth graders. Still, it was the first time that Finucan and her Science Center colleague Maggie Fonner, who would be co-teaching the lesson, were meeting them.

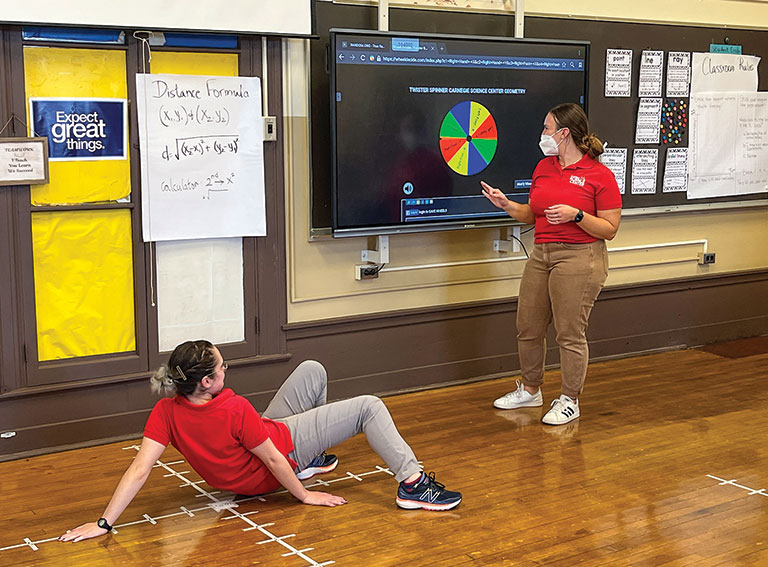

Sensing a post-lunch lull, Finucan and Fonner made quick introductions and jumped right into the games.

of Twister.

First was Twister. Three students who volunteered went to their separate coordinate grids, which were laid out on the floor with masking tape. As Fonner spun a wheel and called out the coordinates—“Left foot, X on five!” “Right foot, Y, two!”—each student stretched across the floor to reach it.

Gradually, the rest of the students began to engage, watching the action in the center of the floor. One group of boys cheered on a classmate, a wiry boy just a shade over 5 feet tall, as he reached a right arm between pretzel-twisted legs to become the eventual winner. His prize—a science-themed sticker of his choice.

Battleship proved more involved. Using the same grids taped to the floor, the class went about playing the classic Milton Bradley war strategy game, with Post-it notes stuck along coordinates like the “pegs” of the ships.

The class was split into two teams, with one team going into a separate room to set up their “game board.” They used hand-held radios to call in strikes on their opponent.

Rounds of back and forth followed before the Twister winner, on the advice of two teammates making an informed guess based on their previous misses, called in “three, negative one.”

“That’s a hit!” came the reply over the radio.

They began “seeing the board,” with each called-in coordinate finding its target. Good- natured trash talking ensued. After about a half-hour, a clear winner was emerging. But then time ran out. Class was over.

Before leaving, the students had one final task—to indicate their feelings about the lesson. Each student was given a colored magnet and asked to plot their response on a grid by the door. Along the x-axis was “I know a lot about coordinates.” The y-axis was “I’m having fun at school today!”

The responses along the x-axis were all over the place, but along the y-axis, the magnets were concentrated at the top—they had fun.

It Takes Time

Science Center educators taught the coordinates lesson to four more groups over two days. It represented two months of work for a single 80-minute lesson. Ramgopal considers it a success.

“The coordinates are one particular skill, which is like the base in geometry. If you don’t know how to plot points, then you’re not going into polygons, you’re not going to be able to draw shapes, you’re not going to know areas,” Ramgopal says. “It just rolls over into other places.”

The creative lesson plan also served as a foundation from which the relationship between the Science Center and the Perry community can grow. Science Center educators are coming back for another weeklong mini-unit with the current Perry ninth graders in the spring, just as they did the previous school year.

The hope is to have Science Center educators return each semester and interact with students throughout their high school experience, following ninth graders through their graduation, and maybe beyond. Each interaction deepens the relationship.

Progress is incremental. White is quick to point out that efforts to turn Perry into a top-performing school began five years ago when the initiative was first funded by the Buhl Foundation.

“It’s been slow and steady progress because we want to set it up for success,” White says. “I think that’s where things go south really quickly for program implementation in schools, because people want to do something, they fund it for a year or two, and they say, ‘OK, what did you accomplish?’ And it’s not that easy.”

Receive more stories in your email

Sign up