Ten giant towers of gold Mylar balloons float upward in the Hall of Sculpture, a two-tiered white marble temple modeled on the Parthenon.

Inside this hushed cavern of antiquity at Carnegie Museum of Art, plaster replicas of Greek and Roman statues arranged on an upper balcony gaze at the installation featured as part of the 58th Carnegie International.

The stark visual contrast between neoclassical aesthetic and those shimmering balloons is an irresistible, made-for-Instagram moment.

Each balloon is shaped like an English alphabet letter. Titled right?, this installation by Turkish artist Banu Cennetoglu spells out the first 10 articles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, a 1948 agreement that leaders from hundreds of countries signed three years after World War II ended.

As the balloons deflate—something they are doing far faster than anticipated—visitors can consider what it will take to protect freedom of religious expression, freedom of speech, and freedom from slavery.

“We are surprised by the rate at which these articles are deflating,” says Ryan Inouye, associate curator of the International, who worked with Sohrab Mohebbi, the Kathe and Jim Patrinos Curator of the 58th Carnegie International, curatorial assistant Talia Heiman, and a large team of advisers and associates.

Inouye notes that some visitors who photographed themselves with the helium-filled balloons, then posted the pictures on social media, were a tad embarrassed after learning of the serious message that underlies the artwork. Kettlebells anchor the balloons to the floor, a visual suggestion that upholding the shiny promise of human rights remains a heavy lift for humanity.

The 58th Carnegie International, which opened September 24 and runs through April 2, 2023, is Pittsburgh’s continuation of a 126-year-old conversation with emerging and well-established artists chosen from all over the globe. Andrew Carnegie, the industrialist and philanthropist, started the exhibition in 1896, and it remains the longest-running North American survey of international contemporary art, second worldwide only to the Venice Biennale, founded in 1895. The museum’s leaders have acquired paintings, sculptures, films, installations, and videos from past shows that have become an important part of the overall collection.

Among the more than 100 participating artists and collectives, 25 are from North America; 6 are from the Caribbean; and 47 are from the Middle East and North Africa.

But this International is more than an effort to highlight the art world’s hottest talents. “This is a show about social movements,” explains Dana Bishop-Root, Carnegie Museum of Art’s director of education and public programs.

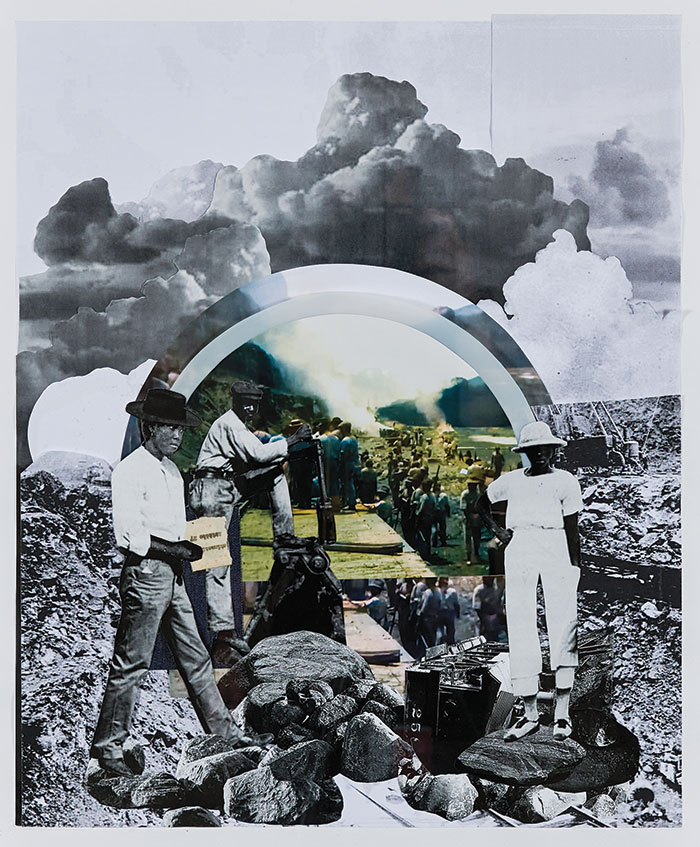

The exhibition showcases artists’ heroic, inventive efforts to archive, record, or reclaim important chunks of history. One example is the black-and-white photographic collages titled What we choose to not see by Panamanian artist Giana De Dier. These collages reveal the resilient Afro-Caribbean women who, during the early 1900s, disguised themselves as men in order to obtain lucrative, backbreaking work building the Panama Canal.

A Political Exhibition

The International’s title—Is it morning for you yet?—is a query and an invitation. In the Mayan Kaqchikel (pronounced Kak-jackal) language indigenous to Central Guatemala, it is a customary greeting to acknowledge that each person’s internal clock and mood varies. It may be morning for you, but it is likely night for someone else.

Among its varied stories, the art in this profoundly political exhibition highlights the United States’ military intervention in armed conflicts during the 20th and 21st centuries, as well as citizens’ struggles against authoritarian governments throughout the world.

“It is certainly a forum for expression for a lot of artists about what their countries have suffered or are suffering,” says Monica Valley, as she took a docent-led tour of the exhibition in late September. An independent curator and museum educator who has worked at the Museum of Modern Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Valley spent much of the pandemic working at the Terra Sancta Museum, housed inside a Jerusalem monastery in Israel. She returned to the U.S. in 2022 and lives in downtown Pittsburgh.

The heart of the exhibition, Inouye explains, is the Hall of Sculpture, a hard architectural space filled with artwork that conveys what he calls “resilience and tenderness.”

On large walls at both ends of the hall’s balcony, 10 frescoes comprise Colors of Grey, by one of more than 25 artists specifically commissioned for this International. Thu Van Tran, an artist born during the Vietnam War, used the six colors of the lethal “rainbow herbicides”—known as Agents Orange, Blue, Green, Pink, Purple, and White—that U.S. military troops sprayed over more than 4.5 million acres of Vietnam, contaminating canals, farms, forests, rice paddies, and rivers.

Courtesy of the artist and Carnegie Museum of Art

In scale and choice of palette, Colors of Grey may remind viewers of Claude Monet’s water lily paintings, one of which resides in Carnegie Museum of Art’s Scaife Galleries. A gifted gardener, Monet cultivated the plants at his Giverny home in France. Some of Monet’s water lily canvases are on view at the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris, the city where Tran lives.

“It is certainly a forum for expression for a lot of artists about what their countries have suffered or are suffering.”

– Monica Valley, An independent curator and museum educator

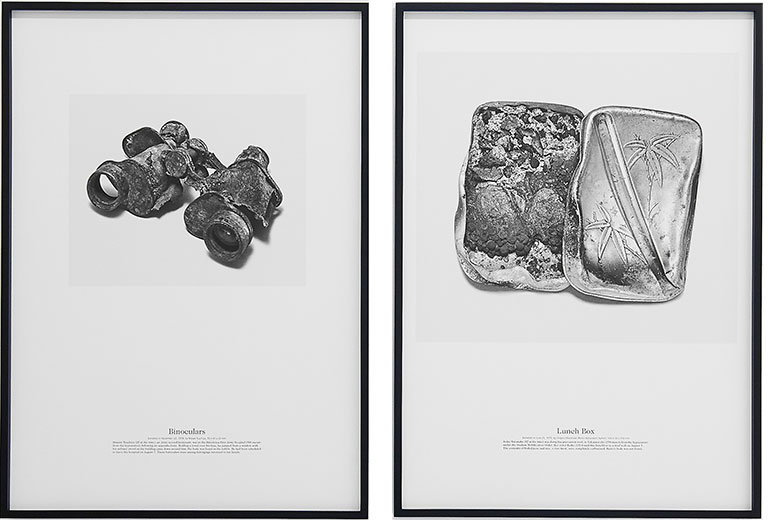

All around the Hall of Sculpture’s first floor are haunting images by Hiromi Tsuchida. For more than half of his 82 years, the Japanese photographer has studied the August 8, 1945, bombing of Hiroshima by the U.S. military near the end of World War II.

The artist meticulously documents objects from the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum’s collection. The result is Hiroshima Collection. One picture shows a torn school uniform worn by Akio Tsukuda, a 13-year-old boy who was doing fire prevention work the day of the bombing. The boy’s father discovered the uniform hanging from a tree branch and kept it; his son’s body was never found.

Hiroshima Collection consists of black-and-white photographs of everyday objects, such as a lunchbox and a pocket watch. The images are composed with a palpable reverence, imbuing each quotidian item with the sacred rarity of a saint’s relic.

Ed Horvat, who lives in Hopwood, Fayette County, visited the 58th International exhibition twice, spending three hours on his first visit. Horvat says he found the exhibition “heavy,” but was nevertheless compelled to return.

“It’s moving in its intensity,” Horvat says, adding that the pictures are so powerful, political, and personal that for a while they became “a repetitive slideshow in his brain.”

Beauty on Barkcloth

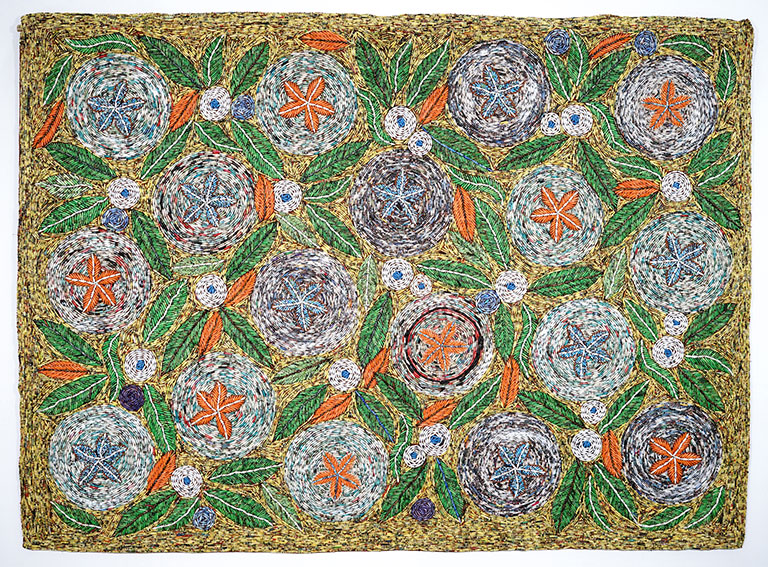

But amid the dark themes there is also light. The Heinz Galleries hold astonishingly vivid, richly textured paintings that appear to be made of shells. Instead, the medium is colorful recycled paper rolled into tiny handmade beads that are sewn onto barkcloth. Think of it as pointillism with paper dots.

The recycled paper folded into beads is gathered from many sources, including magazines, retired school textbooks, and political campaign flyers. The Uganda-born artist, Sanaa Gateja, a trained jeweler, is called the “Bead King” in Kampala, Uganda, where he works with a group of women who assist him and earn income from their painstaking artistic practice.

A different type of beauty—the triumph of indomitable human beings—radiates from color photographs made by LaToya Ruby Frazier, a Braddock, Pennsylvania, native who spent three months of 2021 in Baltimore, Maryland. There, Frazier recorded hours long interviews with 33 community health workers, the front-line foot soldiers who rolled out the COVID-19 vaccine to some of Baltimore’s most vulnerable residents. Frazier photographed each of the community health workers in a place they chose that was meaningful to them, and also taught them to photograph themselves. Her installation earned her the International’s top award, the Carnegie Prize.

A corps of patient advocates who have their neighbors’ trust, the community health workers documented in Frazier’s work educated people about COVID’s threats to public health and helped them navigate the healthcare system to find the right treatment. Beside each picture is the story of what motivated the person featured, plus their recounting of experiences as liaisons with faith leaders, doctors, and government officials. The 36 portraits, attached to 9-foot-tall intravenous poles, stand 6 feet apart, with 18 portraits by Frazier hanging on the front and 18 taken by the community health workers themselves on the back. A black-and-white portrait of Tiffany Scott, the first certified community health worker in Maryland, conveys a palpable mixture of a pioneer’s pride and a superhero’s strength. Scott connected Frazier with other community health workers and also gave her a tour of Baltimore.

Frazier calls this combination of art, archive, history, and installation More Than Conquerors: A Monument for Community Health Workers of Baltimore, Maryland. The artist hopes the artwork will aid community health workers in obtaining better pay and healthcare benefits.

Michele Borkoski, who lives in Oakdale, admires the humanity of Frazier’s work.

“I think that’s really involving the community in the art world,” says Borkoski, a regular patron of previous Carnegie Internationals, as she studied Frazier’s portraits during a visit in early October.

Artists’ choices of medium, materials, and style often reflect the aesthetic and cultural tenor of their times. Several examples are outside the museum’s front entrance on Forbes Avenue. A 40-foot-tall sculpture, Carnegie, was forged from four panels of COR-TEN steel by Richard Serra for the 1985 Carnegie International. The sculpture honors Andrew Carnegie’s cultural and philanthropic contributions to Pittsburgh. Like the nearby Cathedral of Learning, a Gothic classroom building on the University of Pittsburgh campus, the Serra sculpture is also an exercise in placemaking.

“I think that’s really involving the community in the art world.”

– Michele Borkoski, Oakdale Resident, on Latoya Ruby Frazier’s portraits of community health workers in Baltimore

“One conceptual, art historical thread through which I think about Richard Serra’s work is how the scale of and material with which he made his sculptures was in conversation with new typologies of architecture that would define the American city in the second half of the 20th century,” Inouye says. “I think of this as the context in which Serra was working.”

Tishan Hsu, who was born in Boston, Massachusetts, made three artworks this year for the International. Two of them, displayed near the Carnegie sculpture, are especially colorful and curvy: car-grass-screen and car-body-screen.

Hsu has spent more than 40 years thinking about the acceleration of technology and artificial intelligence and how both affect our bodies, behavior, and the environment, Inouye says.

“In Hsu’s work, we have encounters with surfaces, forms, and imagery that we are more used to experiencing on our screens or in the so-called digital domain,” he explains. “But is the digital any less ‘real’ than a street or building when so much digital infrastructure shapes the way we think, live, and relate to one another? Hsu’s work helps me think through such questions about present-day life and our surroundings.”

Hope for peace

Two International installations that are especially striking are Julian Abraham’s OK Studio, 2021 and Dia al-Azzawi’s Ruins of Two Cities: Mosul and Aleppo.

The organic evolution of OK Studio, 2021 by Julian Abraham “Togar” began during the March 2020 lockdown of the COVID-19 pandemic. At the time, he was living in Amsterdam as an artist in residence at the Rijksakademie. He bought a drum, and soon other artists who heard his rhythmic beats joined him. OK Studio, 2021 includes instruments, video, nine automated ocean drums, and gongs.

Witty text paintings on the studio walls are drawn from sonic culture. “You May Say I’m a Drummer, But I’m Not the Only One” sounds like a variation on a line from Imagine, the 1971 song John Lennon wrote as the Vietnam War raged. “You may say I’m a dreamer, but I’m not the only one,” Lennon sang softly in his understated wish for world peace.

But war remains a constant, and Dia al-Azzawi’s large, bird’s-eye view of Mosul, Iraq, and Aleppo, Syria, shows how these ancient cities have nearly been leveled in recent history.

The artist, who was born in Baghdad and lives in London, cast the three-dimensional model out of polyester resin, calling it Ruins of Two Cities: Mosul and Aleppo. For millennia, Mosul and Aleppo were razed and rebuilt, remaining centers of artistic endeavor, culture, and commerce.

Monica Valley, the independent curator, has visited Aleppo and Mosul, an experience that immediately connected her with al-Azzawi’s portrayal of ancient urban ruins.

In the Middle East, Valley says, “You are surrounded by ruins. … You can see the hand of time everywhere. And yet people live in ruins, live in walls that are 800 years old, conduct their daily lives, surf the Internet, and talk with their cellphones.”

Valley believes al-Azzawi deliberately made the work large enough to cover nearly the entire floor of a single gallery.

“He is very clear and very exact about how he lays out the grid of these cities. You can’t escape the details. He’s there. He’s seen it,” Valley says.

The scale of the work, she adds, “catches your eye. It’s very tactile and it’s something that hooks you, that bird’s-eye view. You have a position of power. He wants you to almost take ownership of it.”

Krista Belle Stewart literally did take ownership of land when her mother, Seraphine, gave her 50 acres in the Okanagan Nation. Stewart, who grew up on a First Nations reservation in Canada, dug up some of the land and carried it around in a suitcase. Her wall mural, titled Eye Eye, features rich tones of ocher, terra cotta, and umber. The massive mural is displayed inside the museum’s fountain entry. Stewart transported the land from her reservation in the form of a tile and mixed it with water to create pigment for the mural—a slow, meditative process.

JJ Potasiewicz lives in Ben Avon and works remotely as a design studio manager for a San Francisco company. He called the 58th Carnegie International “the most international” and the “most transporting” art show he has seen in quite awhile.

A notable feature of the 58th International is how far beyond U.S. borders it reached in choosing the organizers of the exhibition. Sohrab Mohebbi is the first person from a West Asian nation to organize a Carnegie International.

Now director of SculptureCenter in Long Island City, New York, Mohebbi, who was born in Iran and is now a U.S. citizen, studied photography at Tehran Art University, then curatorial studies at Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York.

Mohebbi hopes that visitors to this exhibition will realize that one of the show’s messages is that, “trying to understand others and approach other cultures” is also a way of crossing borders.

The 58th Carnegie International, presented by Bank of America, is made possible by leadership support from Kathe and Jim Patrinos.

Major support is provided by the Carnegie International Endowment, The Fine Foundation, the Jill and Peter Kraus Endowment for Contemporary Art, and the Carnegie Luminaries. Significant support is provided by Teiger Foundation, The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, The Susan J. and Martin G. McGuinn Exhibition Fund, Henry L. Hillman Foundation, and the Keystone Members of the Carnegie International. The 58th Carnegie International has been made possible in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities.

This project is supported in part by the National Endowment for the Arts. Generous support is provided by the The Heinz Endowments, the Heinz Family Foundation, the Louisa S. Rosenthal Family Fund, and the Friends of the Carnegie International.

Additional support is provided by the Akers Gerber Foundation, Carnegie Mellon University School of Art, Buchanan Ingersoll and Rooney, Highmark Blue Cross Blue Shield and Allegheny Health Network, NOVA Chemicals, Sotheby’s, Fort Pitt Capital, the Henry Moore Foundation, Advanced Auto Parts, Giant Eagle Foundation, UPMC and UPMC Health Plan, the Japan Foundation, the Fans of the Carnegie International, and the Carnegie Collective.

This program is supported as part of the Dutch Culture USA program by the Consulate General of the Netherlands in New York. This exhibition is supported by Etant donnés Contemporary Art, a program from Villa Albertine and FACE Foundation, in partnership with the French Embassy of the United States.