Who is Marisol? It’s a question that’s clung to the artist for decades. In her heyday, the question was framed metaphorically as a deep analysis of the sculptor born María Sol Escobar, her work, and her enigmatic personality. These days, it’s a more basic query, as most people in the United States don’t recognize her name or know that Marisol was once an enormously famous artist, and someone who Andy Warhol admired and aspired to emulate.

Andy Warhol, Marisol – Stop Motion, 1964, 16 mm film, black-and-white, silent, 3 minutes © The Andy Warhol Museum, All rights reserved

A new exhibition hopes to help reclaim the late artist’s place in the Pop art story and return from the fringes her inventive and playful life-size sculptures that she carved from wood and accessorized with paint and found objects, from shoes and clothes to wallpaper and chairs. Marisol and Warhol Take New York, on view at The Andy Warhol Museum through Feb. 14, 2022, explores the twin trajectories of the two artists during the rise of Pop art in the 1960s. It pushes back against the notion that New York Pop was defined by the “New York Five”—Warhol, Jasper Johns, Roy Lichtenstein, Robert Rauschenberg, and James Rosenquist—all white men.

“Somehow, [Marisol] was written into the history as a footnote, a marginal figure, when in actuality she was at the center. And not only was she at the center, she influenced one of the most celebrated figures in the history of the movement: Warhol.” – Jessica Beck, The Warhol’s Milton Fine Curator of Art

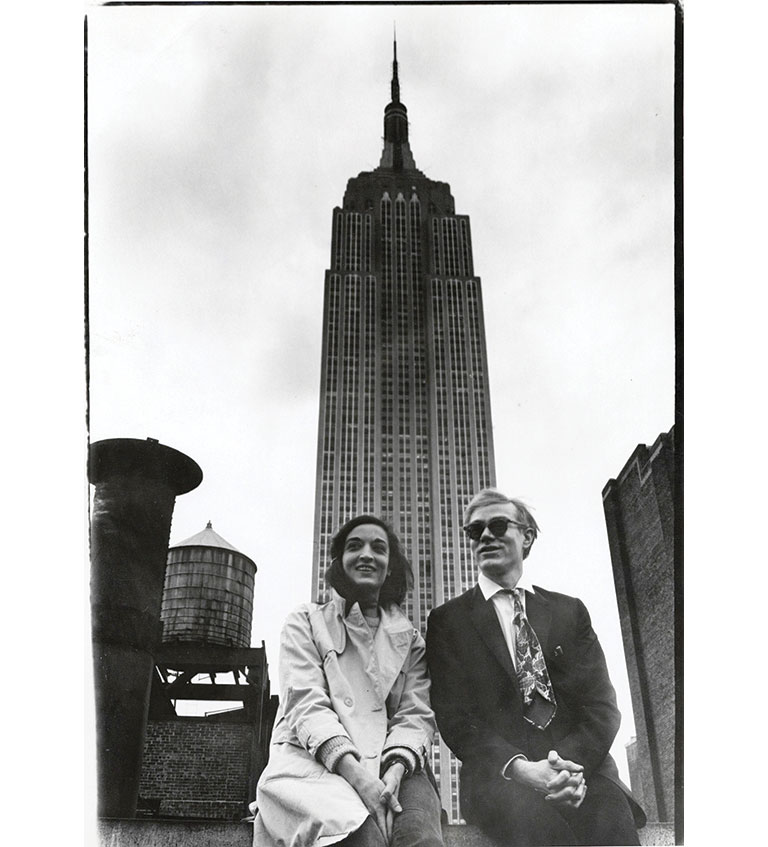

David McCabe, Andy Warhol and Marisol with the Empire State Building, 1965, The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. Photograph by David McCabe

“Marisol was just as influential, just as famous, and just as important if not more so than some of these men,” says Jessica Beck, The Warhol’s Milton Fine Curator of Art and organizer of the exhibition. “Marisol was a hugely popular, famous artist at the beginning of her career, from 1960 to 1968. After this golden moment in New York, it’s as if all of her success was erased. Somehow, she was written into history as a footnote, a marginal figure, when in actuality she was at the center. And not only was she at the center, she influenced one of the most celebrated figures in the history of the movement: Warhol.”

A “Beautiful, Sentimental Connection”

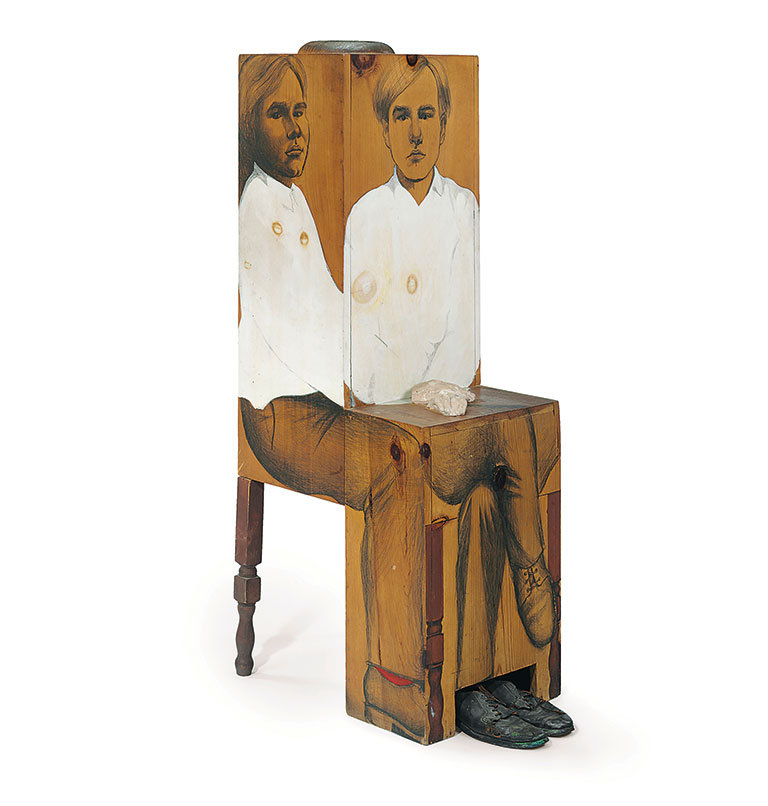

Warhol and Marisol first met in the early ’60s. One of Warhol’s datebooks records a dinner with artist Frank Stella and Marisol in March of 1962, and it’s clear that Marisol and Warhol quickly became enamored with each other. That same year, Marisol made a three-dimensional portrait of her fast friend, a sculpture depicting a pensive Warhol sitting in a chair, his actual shoes on the floor and a cast of Marisol’s hands folded in his lap, which Beck describes as a “beautiful, sentimental connection.” Warhol put Marisol at the center of his lens in 1963–1964, featuring her as a playful collaborator in some of his earliest and most experimental films, including Bob Indiana, Etc., Kiss, and a Screen Test. In a New York Times interview in 1965, Warhol praised Marisol as “the first girl artist with glamour.” To him, that was “a true pinnacle of success,” Beck says, and not a flippant remark.

Marisol, Andy, 1962–63, Guggenheim Abu Dhabi, Image Credit: © Acquavella LLC 1962-63, © 2021 Estate of Marisol/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Warhol likely watched and learned from Marisol’s relationship with the press, as she always left them wanting more. When journalists in the 1960s wrote about Marisol, they fixated on her beauty and gentle voice. The New York Times piece, in which Warhol lauded Marisol, detailed her “chic, bones-and-hollows face” and “faraway whispery voice, toneless as a sleepwalker’s.” The press struggled to situate the work critically and instead focused on its materiality and often denigrated the wit of her sculptures—a sentiment heralded in the work of other Pop artists— as a weakness inherent in the work. Warhol’s early interviews were more open and transparent about his thinking, Beck says, but eventually there’s a switch where he creates the guarded and distant Warhol “persona” that was perhaps influenced by Marisol.

Though they inhabited the same New York art scene in the 1960s, the two arrived in Manhattan with completely different lived experiences. Born in 1928, Warhol grew up with immigrant parents scraping together a living in Pittsburgh. Marisol was born two years later in Paris to wealthy, cosmopolitan Venezuelan parents. Both artists lost a parent at a young age. Warhol’s father died when Warhol was 14; Marisol’s mother died by suicide when Marisol was 11. She chose not to speak for years afterward, except when necessary. Both artists found their way to New York City by 1950. Marisol, who in early years lived between the Venezuelan capital of Caracas and New York and attended art schools in Los Angeles and Paris, quickly entered New York’s elite gallery scene. She secured a solo show with the newly opened Leo Castelli Gallery, while Warhol worked in commercial design and tried to attract galleries’ attention. (In 1958, Marisol exhibited at Carnegie Museum of Art in what’s now known as the Carnegie International.)

Marisol was creating what Beck describes as “true assemblage work,” collaging found objects along with painting, drawing, and sculpted wood together in a way that, while in dialogue with the early works of Rauschenberg and Johns, engaged more directly with contemporary media and photography. She also incorporated artistic influences of pre-Columbian and Mexican art to create multi-layered, multi-national works of art. Marisol’s art “walks this interesting line with gendered materials,” notes Beck, as Marisol merged “masculine” carpentry work along with delicate and “feminine” casts. The boxy and original sculptures were featured on the cover of Time; Gloria Steinem profiled her for Glamour.

Though Marisol and Warhol hailed from different backgrounds and used different mediums—carpentry tools and wood for the former; primarily paint and canvas for the latter—their work explored similar themes, often with related imagery. The echoes of Marisol’s work can be seen in Warhol’s. In Marisol and Warhol Take New York, the art is hung as if it’s in conversation. Both artists mined Pop culture, taking Coca-Cola and the Kennedys as their subjects, as well as themes of gender and self-portraiture.

Andy Warhol, You’re In, 1967 © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

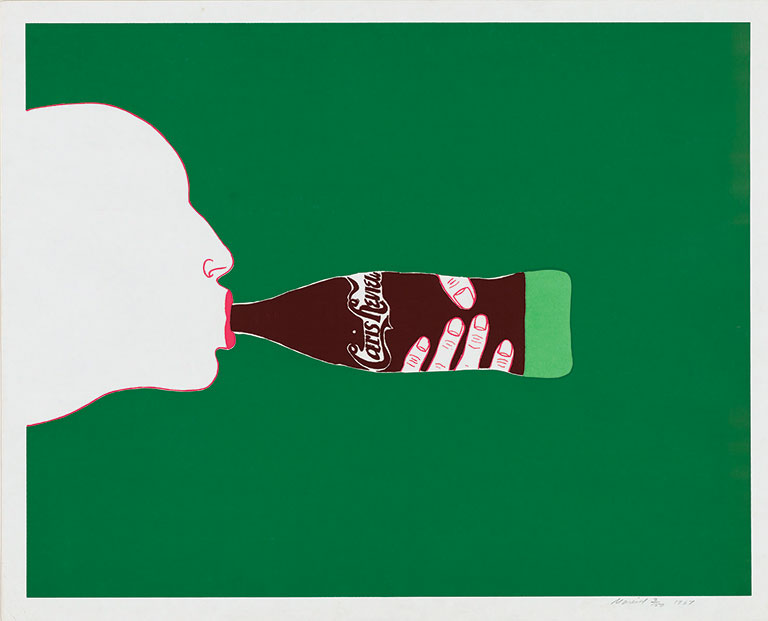

Marisol, Paris Review, 1967, Gift of Page, Arbitrio and Resen, Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, NY, © 2021 Estate of Marisol/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

With their Coca-Cola imagery, the artists explored what Jennifer Josten, associate professor of history of art and architecture at the University of Pittsburgh, describes as “an emblem of American commercial and cultural imperialism.” Both depicted Coca-Cola in the early 1960s, Warhol in bold black-and-white paintings and Marisol in a sculpture titled Love depicting half of a face (likely her own) with an actual filled Coke bottle standing upright in its mouth. They both took up the soda pop iconography again in 1967, this time with Warhol’s three-dimensional silver-painted bottles in a yellow crate and Marisol’s silkscreen print reminiscent of Love.

As for the Kennedys, both artists captured the country’s fascination with the reigning political couple. Marisol’s 1961 The Kennedy Family illustrates the family of four at the christening of John Jr., with Jackie holding her newborn. Several years later, after John F. Kennedy’s assassination, Warhol created his iconic Jackie series in blue and black and gold.

Marisol’s 1961 sculpture The Kennedy Family, paired with Andy Warhol’s famous Jackie series, illustrates the foursome at the christening of John Jr., with Jackie holding the newborn.

The concept of gender plays a role in both artists’ work, as well. During this period, Marisol often focused on family structure. The media hounded her with questions about who she was dating, if she’d marry, and if she’d have children. As if in answer to those questions, one of her sculptures depicts her having dinner with herself (the main course is a TV dinner); another shows her marrying herself. Warhol, meanwhile, was exploring subversive gay messaging in his paintings, including his series of dance diagrams. One of his earliest Pop paintings, Make Him Want You, was inspired by a dating advertisement in the National Enquirer. Warhol coupled the phrase with an American flag, featuring a gender-normative couple in place of its stars.

Marisol’s largest assemblage, The Party, is installed at The Warhol with Andy Warhol’s pink-and-yellow Cow Wallpaper to dramatic effect. All 15 of the figures mirror Marisol’s facial features. | Photo: Abby Warhola

Marisol’s own likeness often appears in her work. All 15 figures in her largest assemblage, The Party—installed at The Warhol beside Warhol’s pink-and-yellow Cow Wallpaper—mirror her facial features. Warhol, who spent a lifetime revising the image he presented to the world, is known for his self-portraits, two of which conclude the exhibition.

The Queen and King of Pop

After representing Venezuela in the 1968 Venice Biennale, where she showed seven sculptures, including Andy Warhol and The Party, Marisol decided to take time away to travel. When she returned to the art stage five years later, her work strayed from her signature mix of Pop and folk and never again attracted the level of attention it had before in New York. Though she and Warhol were once heralded as the queen and king of Pop, she fell into relative obscurity, and was written out of the retelling of the Pop narrative, until the past decade. Her story is one that Beck describes as “a story of the gendering of art history that happens around this period.” Beck herself didn’t learn about Marisol during art history classes and instead discovered her by seeing the artist’s work at museums. Back in the ’60s, as many as 2,000 people would crowd into a gallery each day to see Marisol’s art, but it seems the artist was quickly forgotten by the mainstream—until now.

Art historian Josten, who has long been familiar with Marisol as part of her research on Latin American artists, is thrilled that the exhibition will help her students learn about Marisol’s work alongside Warhol’s.

“A show like this does the work of reintegrating Marisol into a broader art historical narrative and discourse, helping to secure her role in this milieu of creativity and commerce and politics in New York in the 1960s,” says Josten.

Marisol, Dinner Date, 1963, Yale University Art Gallery, Gift of Susan Morse Hilles © 2021 Estate of Marisol/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

What would the mysterious Marisol think about her reemergence? It’s impossible to know, as she died in 2016 at the age of 85, but there are some clues.

In that landmark 1965 New York Times profile, Marisol is quoted as saying, “It doesn’t make any real difference whether I continue to be successful. If one artist that you respect says he likes your work, that’s the important thing. I could go on working even unrecognized.” In a less prophetic but more hopeful response, the reporter wrote, “She probably won’t ever have to. Though fashions in art change rapidly these days, Marisol’s work has high survival value.” Indeed, the work survives today, and thanks to The Warhol, it’s having a well-earned revival.

“The longer-term goal,” says Beck, “is to put Marisol and her work back into the canon and to reclaim her place in the center of this New York story.”

Marisol artwork © 2021 Estate of Marisol/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Andy Warhol Artwork © 2021 The Andy Warhol Foundation

Marisol and Warhol Take New York is presented by the Richard King Mellon Foundation and generously supported by the Terra Foundation for American Art, Jim Spencer and Michael Lin, Alice and Yaso Snyder and the WP Snyder Charitable Fund, Dawn and Chris Fleischner, and Highmark Blue Cross Blue Shield.