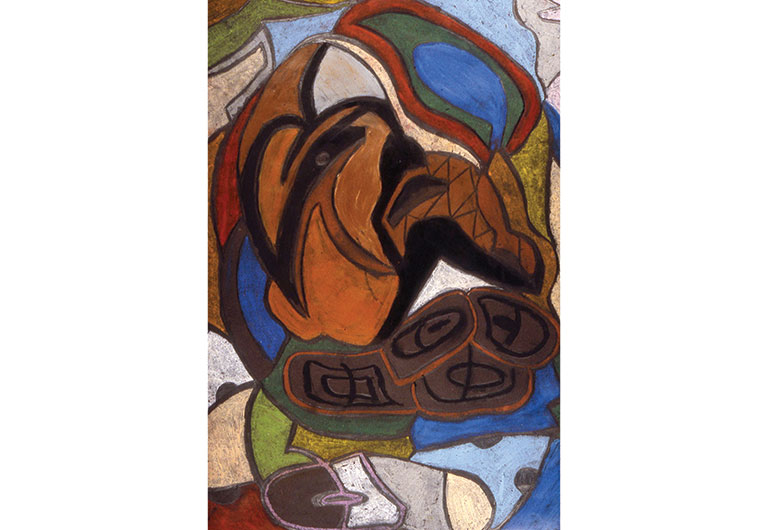

A striking abstract pastel with bold earth tones hangs in ceramicist Sharif Bey’s Syracuse family room. He made the artwork nearly four decades ago as an eighth grader in Carnegie Museum of Art’s Saturday art classes.

“I remember looking at masks and making this abstract interpretation of the images that I was seeing in natural history,” recalls Bey, referencing his teenage encounters with the collections at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. The oil pastel is part of an award-winning portfolio of work by Bey from the mid-1980s that he still vividly remembers. After all, it earned him a spot in a prestigious pre-college arts program at Carnegie Mellon University.

A mask study Bey created in eighth grade while attending Saturday art classes at Carnegie Museum of Art.

“To me, receiving the award meant being distinguished among distinguished kids, and that kind of motivation means a lot to a kid who, well, that was what I was striving to be,” says Bey, now 47 with work in major museum collections around the country and in U.S. embassies in Sudan and Indonesia.

“I had seven brothers, six of whom who are older than me. That’s a lot of shoes to fill and a big shadow to shine from.”

Bey was 9 years old when his art teacher at Beltzhoover Elementary School recommended him for the museum classes. His mother and aunt would take turns driving him and several female cousins from their working-class neighborhood to the museums in Oakland until Bey became old enough to catch a pair of city buses alone.

Having regular access to a building brimming with both art and natural history objects was a formative experience, Bey says, because he was “free to wander and wonder” unencumbered and respond to works of art at his own pace.

“I’m a big advocate of unadulterated curiosity, and the downtime at the museum was just as beneficial as the instruction. The level of autonomy given to us was a really special and unique part of the experience.”– Sharif Bey

Sharif Bey with his 2017 necklace Louie Bones-Omega. Photo: Dusty Herbig

“I’m a big advocate of unadulterated curiosity, and the downtime at the museum was just as beneficial as the instruction,” says Bey, who now lives in Syracuse and is an associate professor of art at Syracuse University. “The level of autonomy given to us was a really special and unique part of the experience.”

In 2018, Carnegie Museum of Art acquired five of Bey’s sculptures (two of which were later included in that year’s Renwick Invitational, a prestigious biennial at the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum). As part of that dialogue, Rachel Delphia, the Alan G. and Jane A. Lehman Curator of Decorative Arts and Design, invited Bey to return to his childhood museum for a solo exhibition with an inspiring framework: to reconsider the collections that were so influential in his youth through the critical eye of an artist, educator, and scholar now in midlife.

“Sharif is engaging both his past and present, a process he calls auto-archaeology,” says Delphia. “He’s taking on some big questions, including how he learned to believe in himself as an artist, and who has creative agency.”

Over two years, the pair spent time with museum staff in art storage and in the galleries in search of Bey’s “old friends,” works he would go back to time and again, even sometimes decades later. He also hung out with museum collection managers, paleontologists, anthropologists, and ornithologists, exchanging stories and ideas, and mining their respective collections.

The result is Sharif Bey: Excavations, on view through March 6, 2022, featuring Bey’s contemporary ceramic and mixed-media sculptures alongside museum artworks that moved and challenged him as a young artist. The exhibition also showcases a few wonder-filled surprises: site-specific installations created by Bey that incorporate artifacts and specimens from the Museum of Natural History’s collections.

The only item on Bey’s wish list that he couldn’t pull off: squeezing the 20-foot-long lower jawbone of a sperm whale—an early influence—into the gallery space. “It looks exactly to me like what a 20th-century modernist sculptor would have wanted to achieve,” says Bey.

Resurfacing the Past

A potter at heart, Bey is a maker of what he calls “subtle” functional wares and decorated vessels. His work reflects an interest in the visual heritage of Africa and Oceania, and contemporary African American culture. In his current sculptures, Bey asks viewers to reconsider historic narratives and notions of power, surfacing social and political issues from the perspective of someone who is both Black and Muslim.

One object that has remained a touchstone for Bey over decades is the Kongo peoples’ nkisi nkondi power figure, a West African tribal sculpture made mostly of wood and iron and used for spiritual requests.

Unknown Kongo, Nkisi nkondi (power figure), c. 1875, Carnegie Museum of Art, Gift of Jay C. Leff, by exchange with Carnegie Museum of Natural History

Above is the nkisi nkondi power figure that has been influential to Bey’s practice. He adapts the use of nails as decorative patterning in his own figures, including in the Boilermaker below.

Sharif Bey, Boilermaker: Tweet, 2021, Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Bryan Conley

“I remember in elementary school really being taken by it,” recalls Bey, noting that it’s a figure he would visit frequently at Carnegie Museum of Art, including when he would return as an adult to see the Carnegie Internationals. “When I first encountered it, I knew very little about it. I was drawn to it aesthetically. It evoked a lot of curiosity.”

Nails piercing the figure are a defining feature of the work, which Bey borrows for his own figurative sculptures, including a group highlighted in the exhibition and impaled by both nails and shards of ceramics. Bey adapts the motif as intimate, decorative patterning.

Having been reared in an “anti-imperialist household,” the artist says he’s always been drawn to non-Western art. “I was taught to question narratives stemming from white supremacy,” says Bey. “I was taught in many ways to look away—Liz Taylor was not what Cleopatra probably looked like and Christopher Reeve wasn’t my Superman. We didn’t watch TV shows that celebrated white heroes and marginalized or stereotyped people of color. We didn’t play with white action figures.” Pre-internet, there wasn’t a lot of easily accessible context for thinking about art from other places outside of PBS, National Geographic, and the museums, says Bey. He and his 11 siblings sometimes dreamed up their own characters and creations.

Today, Bey’s pint-sized Boilermaker figure integrates his interest in West African sculpture with a piece of Pittsburgh’s industrial history and a nod to three generations of boilermakers in his family. The Protest Shield (one of a series), which incorporates nails and ceremonial elements with a crown of fists, emerged during the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020. “I imagine these shields as a protective armor to counter forces of police officers in riot gear,” says Bey.

Sharif Bey, Protest Shield, 2020, Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Bryan Conley

Putting Family First

Manchester Craftsmen’s Guild on Pittsburgh’s North Side was also a formative place for Bey; instructors in the ceramics program recruited him for their after-school apprenticeship program in pottery when he was 14, and it was there that he fell in love with “playing with mud and seeing what it reveals.” Like at the museum, the teachers didn’t sit behind a desk; they were working artists. Bey, more by serendipity than plan at first, followed in their footsteps, teaching at Manchester and other out-of-school artmaking spaces.

Having earned an MFA in studio art from the University of North Carolina, Bey decided to pursue his doctorate in art education at Pennsylvania State University. “Of all the stories I tell of being supported by my community, none of them were from my public school, and I wanted to know why,” says Bey. And he wanted to help make the kinds of community-based experiences that were available to him more widely available to others who look like him.

But while pursuing his PhD, Bey was also teaching and juggling the duties of being a husband and father to a toddler and newborn. He knew something had to change to prioritize his family while also still making art.

Being locked away in a studio “felt selfish,” says Bey, who has always been a prolific maker. “I knew there had to be a rhythm that was conducive to our lifestyle. I didn’t want to depend on any specific place or equipment.”

He set aside the wheel-thrown teapots and jars and started working on a smaller scale, setting up mini dedicated working spaces around his house furnished with basic clay tools. He began pinching clay by hand into small containers, something he could do in the kitchen or living room in 10- or 15-minute bursts while his kids played nearby.

Sharif Bey, Raptor Ruff, 2018, Carnegie Museum of Art, Purchase, gift of Walter Read Hovey, by exchange. Photo: Bryan Conley

Inspired by images of a young Berber woman in North Africa wearing a series of amber-beaded necklaces, Bey started stringing together the small pinch pots. This move to making adornments using pinch-pot vessels as beads was influenced by a conversation with renowned potter Don Reitz. “In talking about this own practice, he told me, ‘I don’t make pots. I make sculptures of pots,’” Bey recalls. The simple but profound idea resonated with Bey and set him on new, and in some ways freeing, adventures.

Many of Bey’s necklaces are large and weighty, like the flashy necklaces associated with bling culture. For Bey, the form is an ongoing exploration of power and identity that also harkens back to the 1960s when beads in African American culture were viewed as symbols of resistance and protest. The beads in Bey’s necklaces often draw on forms inspired by the natural world, such as bird skulls, tusks, raptor claws, and now dinosaur vertebrae.

Tapping Into the Natural World

During a 2017-2018 residency at Pittsburgh Glass Center, the artist tried his hand at glass for the first time, creating a new series of necklace forms using glass beads. Several are on view in Excavations, including O’Keeffe’s Leis, which connects not only to Bey’s childhood fascination with the Museum of Natural History’s iconic dinosaur skeletons, but also the steel structures that sustain them, which Bey and his welder father consider sculptures in their own right.

“What’s always stuck with me about natural history is its stillness. And the fact that it belongs to no one and everyone. There should be a humility that comes out of the awesomeness that was here long before us. It’s nothing you can bag, tag, and brand.” – Sharif Bey

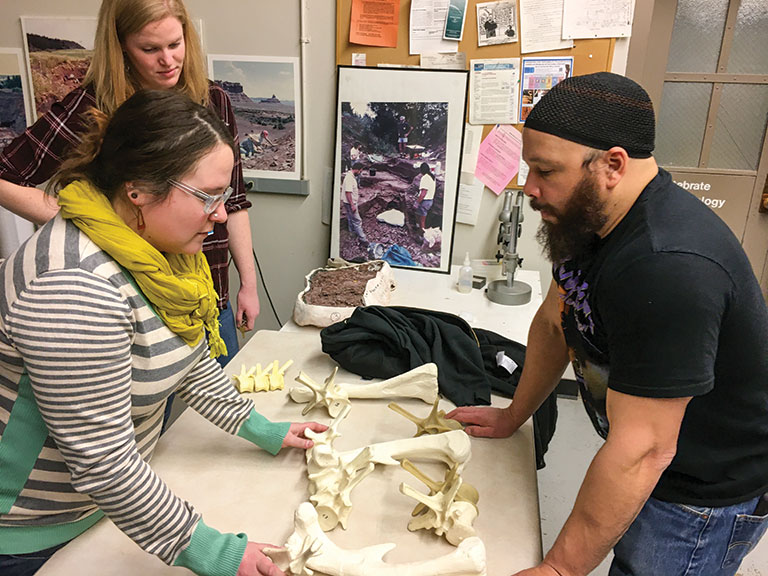

The necklace’s amber-colored beads are made from vertebrae casts of two giant herbivores: the duck-billed Edmontosaurus (which falls to the battling T. rex in the museum’s blockbuster exhibition) and the world’s most complete juvenile Apatosaurus, both discovered by Carnegie Museum paleontologists. The resin casts Bey uses were expertly made by Linsly Church, curatorial assistant for vertebrate paleontology. And the necklace’s title: a tip of the hat to painter Georgia O’Keeffe, who had her own fascination with skeletons.

“What’s always stuck with me about natural history is its stillness,” says Bey. “And the fact that it belongs to no one and everyone. There should be a humility that comes out of the awesomeness that was here long before us. It’s nothing you can bag, tag, and brand.”

At top, Sharif Bey behind the scenes in Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s ornithology and vertebrate paleontology collections. He’s looking at fossil casts with glass artist and collaborator Ashley McFarland and curatorial assistant for vertebrate paleontology Linsly Church. Above is a detail of Bey’s 2021 necklace O’Keeffe’s Leis, made from casts of dinosaur vertebrae.

Returning to family, Bey includes in the exhibition a pair of detailed carvings made by his father, Nathaniel Bey, when his father was 14. Only recently did Bey learn that his father, too, was a museum kid. He preferred to fish, but on rainy days, Carnegie Museums was his destination. Bey paired the carvings with new staffs inspired by Kayapo clubs, which are traditionally used by Indigenous Brazilians in hunting and warfare.

Perhaps the most unexpected works in Excavations are two large-scale, wall-mounted installations comprised of a total of 273 vibrant bird study skins, arranged in radial patterns like a mandala or tapestry, to stunning effect. The birds, part of the museum’s ornithology collection, were collected between 1889 and 1993, primarily in Central and South America.

“I describe them as brushstrokes,” says Bey. But one of the museum guards told him she could only see death, which resonates with the artist.

Sharif Bey, Ornithological Excavation #1 (detail), 2020–2021, Carnegie Museum of Natural History, Collection of Section of Ornithology

“The truth is there’s a lot of death in a museum. There’s a lot of conquest. There’s a lot of acquisitions from displaced people and reappropriation of cultural marvels, and all of that is in some way dead when you bring it to an institution that is not connected at all to its original context,” says Bey.

“That could be the dinosaur, that could be the bird study skins, that could be the whale bone, that could be the [painting by] Mary Cassatt. They’re all connected to something that once was. Part of the challenge for us as museum people is to in some way revitalize that content, and create new contexts for experiencing these things.

“It’s not about righting the wrongs. The question is, ‘What now?’ We could use this time to disparage the white males who conquered the world and brought these things to us, or we can talk about issues of justice, and revitalization, and creating new context for engaging this material for the benefit of education and humanity.”

Sharif Bey: Excavations is made possible by The Bessie F. Anathan Charitable Trust of the Pittsburgh Foundation at the request of Ellen Lehman and Charles Kennel, Arts, Equity, & Education Fund, Dawn and Christopher Fleischner, Brian Wongchaowart, the Ruth Levine Memorial Fund, and The Fellows of Carnegie Museum of Art. Additional publication support is provided by Albertz Benda and Friedman Benda.

Receive more stories in your email

Sign up