The Watering Hole

At the heart of Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s popular Hall of African Wildlife is the Watering Hole diorama and its panoramic view of a variety of animals—gazelles, zebras, giraffes, even a warthog—in the recreated ecosystems of Kenya’s wet and dry savanna. The beloved display’s backstory begins with the adventures of a then-young biologist Childs Frick, the oldest son of Pittsburgh industrialist Henry Clay Frick and Adelaide Howard Childs, who donated to the museum some 500 mammals he collected from 1909 to 1912 on two scientific expeditions to East Africa. A conservationist, Frick didn’t simply take aim at the largest targets; he collected examples of adult females, sub-adults, and juveniles, providing the museum with a more accurate representation of the animal kingdom. He then shipped the treated skins and skeletons back to Pittsburgh where he knew the finest taxidermists awaited their arrival. Remi and Joseph Santens were not just taxidermists; they were artists. Now, more than a century later, their work—complete with amazing details, such as flexing muscles and bulging veins—still infuses the Watering Hole and other museum displays with a striking sense of reality.

Thaddeus G. Mosley, Spatial Occupation, 2018, Carnegie Museum of Art, Gift of the Alex Katz Foundation © Courtesy the artist and Karma, New York

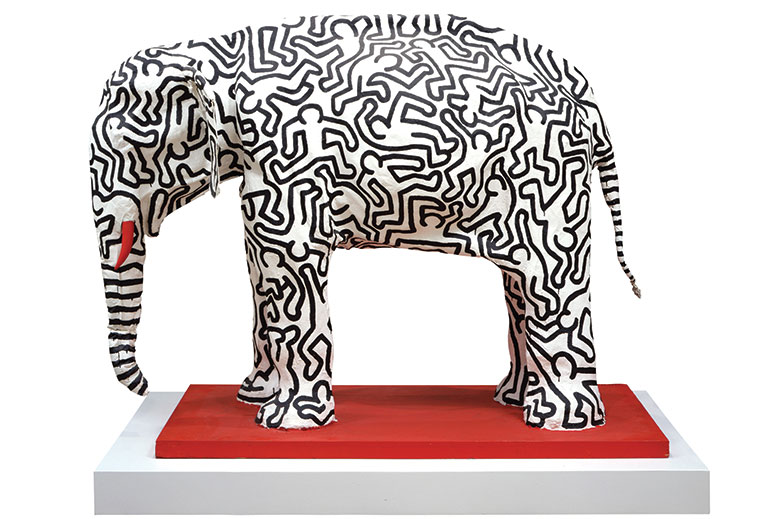

Spatial Occupation by Thaddeus Mosley

An accomplished sculptor who works primarily with wood, Thaddeus Mosley spends hours looking at a trunk’s unique shape, grain, and structure. He waits, not picking up a mallet or chisel until a particular hunk of salvaged timber reveals to him its personality and ultimate destiny. The revelations are staggering. Over more than six decades, the 95-year-old estimates he’s made more than 700 sculptures, many towering creations that combine four or five components and seemingly defy gravity. Mosley grew up in New Castle, Pennsylvania, and studied English and journalism at the University of Pittsburgh. While at Pitt, he would often walk the few blocks to Carnegie Museum of Art. The galleries became his classroom, and the Carnegie International his muse. As a true student of the International—he’s attended every iteration since the 1950s—he couldn’t wait to see the new artists, new techniques, and new ideas on display. In 2018, after a successful career as the quintessential working-class artist, having worked nights for the U.S. Postal Service for 40 years while also making art, Mosley joined the ranks of International artists. He was invited to exhibit a forest of 13 sculptures in the museum’s main lobby and seven more in its outdoor Sculpture Court. Two of them—including Spatial Occupation, a 10-foot-tall creation carved from maple—were acquired by the museum for its permanent collection, joining two other works by Mosley, including Georgia Gate, a spare but expressive sculpture acquired in 1976, nearly a decade after Mosley staged a solo exhibition at the museum.

Andy Warhol, Silver Clouds, 1966 © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

Warhol’s Silver Clouds

When Andy Warhol’s Silver Clouds debuted in 1966, he thought of the metallic pillows as paintings that could “float away.” At the time, Warhol was seriously thinking about abandoning his work on canvas to focus on filmmaking. He collaborated with Bell Labs engineer Billy Klüver to transform the then-new material Scotchpak into an interactive work of art. First shown at the Leo Castelli Gallery in New York City, the clouds notably became part of the design and choreography of Merce Cunningham’s RainForest, which premiered in 1968. To the continued joy of museumgoers, the playful and now wildly popularly installation pieces eventually landed at The Andy Warhol Museum and other museums around the world, where the job of keeping the Silver Clouds aloft requires firm footing. Once a week, Warhol staff members fill a new set of replica inflatables with a proprietary mix of air and pure helium. The concoction is specially formulated to give each balloon enough lift to get off the floor, but not so much that it sticks to the ceiling.

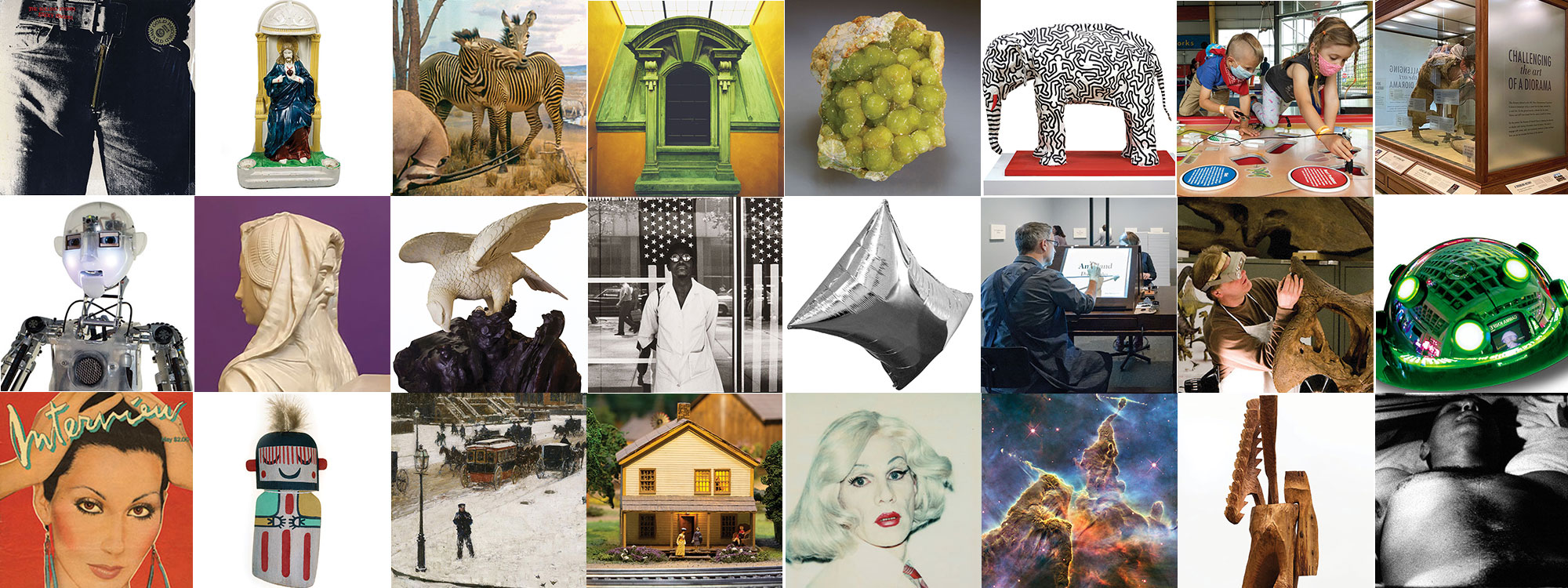

Ming Smith, America Seen Through Stars and Stripes, New York City, NY, c. 1973, Margaret M. Vance Fund © Ming Smith. By permission

America Seen Through Stars and Stripes by Ming Smith

For more than four decades, Ming Smith has used her camera to capture Black life in all its complexity. She left her childhood home of Columbus, Ohio, for New York in the early 1970s after studying microbiology at Howard University. Her early career was marked by significant firsts: She was the first, and for many years the only, female member of the Kamoinge Workshop, an influential collective of Black photographers based in New York; and, in 1978, she was the first Black female photographer to have her work acquired by the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Still, only in the past decade have people begun embracing her unique perspective and style. Noted for her double-exposed prints and for collaging and painting on the surface of her photographs, Smith, now in her 70s, has never slowed down. In 2017, Carnegie Museum of Art acquired her striking 1973 picture America Seen Through Stars and Stripes. With its lone Black figure backed by American flags, this photograph is one of Smith’s most iconic. It sensitively addresses the complexity of U.S. race relations during a critical time in the Civil Rights Movement.

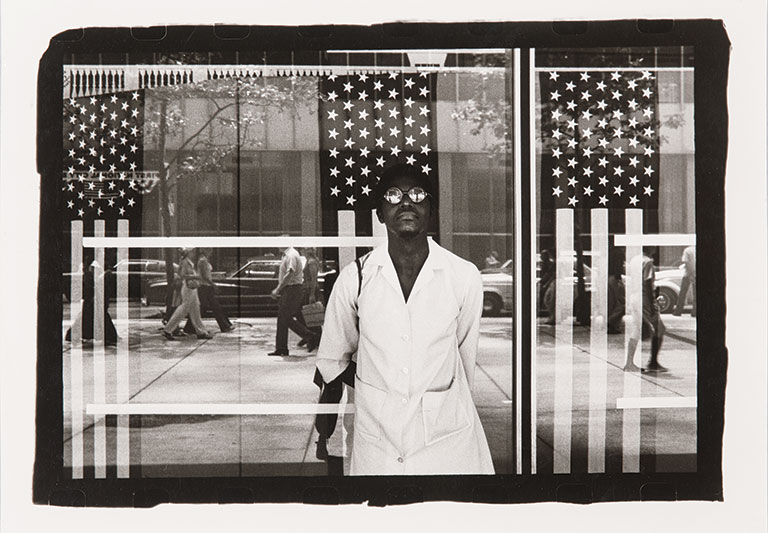

Andy, the RoboThespian

At Pittsburgh’s ultimate robot gathering, he’s at the front of the pack, welcoming visitors to Carnegie Science Center’s roboworld®, the world’s largest permanent robotics exhibition. Known as Andy, the interactive-robot-turned-greeter introduces visitors to the concepts of robotic sensing, thinking, and acting through both preprogrammed actions (an enthusiastic hello) and a touch-screen kiosk that visitors can control. Like many socially interactive robots, part of Andy’s charm is that he engages us by mimicking our bodily expressions and movements. More than 3,000 Pittsburghers and robot fanatics around the world voted in an online poll that christened the modified RoboThespian™—designed and built by Engineered Arts Limited of Cornwall, England—Andy.

Hopi Katsina Dolls

Some 100,000 ethnological and historical objects are in the care of Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s section of anthropology, including some 3,000 dolls. More than just toys—although they certainly serve that important purpose—dolls are found in almost every culture and provide insight into family roles, customs, and traditions. The museum displays a large collection of Hopi Katsina dolls, wooden effigies of supernatural beings who visit the Hopi for about half of every year, in its Alcoa Foundation Hall of American Indians. Traditionally carved from cottonwood root by Hopi men, the dolls are tangible evidence of the katsinam’s power and wisdom. Parents use them to help teach children about Hopi culture and religious beliefs. The Hopi believe that katsinam spirits assist in plant growth, prevent misfortune, and bring rain, provided they are properly respected. Pictured is a Hahay’iwuuti (Grandmother Katsina), made by Manuel Chavarria of First Mesa on the Hopi Reservation, in 1995 or 1996. The Grandmother Katsina is the first katsina given to a child, and this is the flat, “cradle” style that goes in a baby’s bed.

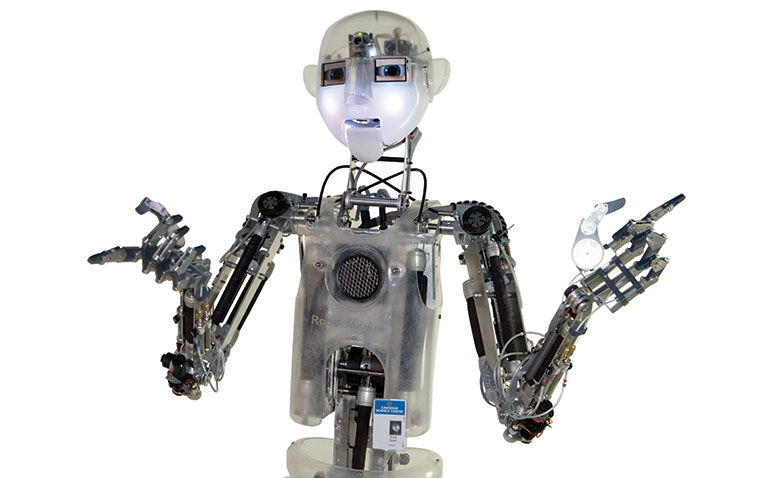

Keith Haring, Untitled (Elephant), 1985, The Andy Warhol Museum; Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc., Keith Haring artwork © Keith Haring Foundation

Keith Haring’s Elephant

Made of papier-mâché, the large Keith Haring elephant that stands tall in the galleries of The Andy Warhol Museum wasn’t constructed by Haring; it was left over from a costume exhibition curated by Diana Vreeland at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Andy Warhol bought the sculpture, which was originally painted pink, as a prop for the star-studded event, and when the show was over it ended up at Warhol’s studio. In a little-known turn of events, Jean-Michel Basquiat—not Haring—first painted on the elephant, giving it white toenails, doodles on its ears, and what resembled a large shock of white hair at the top of its trunk. Fred Hughes, Warhol’s longtime business manager, had the elephant repainted white so that Haring could cover it with his signature figures. In an April 20, 1985, entry in The Andy Warhol Diaries, Warhol says he preferred Basquiat’s version: “Jean Michel and Victor [Hugo] painted some stuff on it, but not much, but still I would’ve kept it a Jean Michel even though it wasn’t much of one, but Fred thought it would be better as a Keith Haring, and so Keith is going to paint it now that it’s white.”

Underground Treasure

Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s renowned mineral collection boasts more than 31,000 specimens in all, many of which were acquired in the 19th century. Among its standouts: a rare suite of minerals from the former Soviet Union; and, as of 2014, the most comprehensive Pennsylvania mineral collection in the world. The acquisition of more than 2,700 specimens from the collection of Bryon Brookmyer, a committed hobbyist, helped the museum reach this significant landmark. Among the stunners: this remarkable wavellite, an aluminum phosphate found in Snyder County, Pennsylvania. More than 2,200 historically important specimens from the William W. Jeffries collection and nearly 5,000 minerals formerly owned by the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia round out the collection that speaks to the rich and sometimes colorful geological history of the Keystone State. An astonishing variety of 300 minerals, including calcite, dolomite, pyrite, and quartz, have been discovered in Pennsylvania, and each reveals a part of Earth’s millennias-old history.

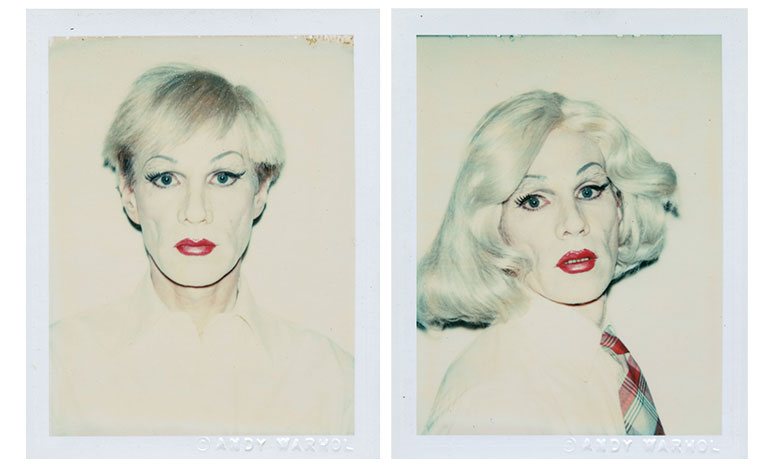

Andy Warhol, Self-Portrait in Drag, 1980-81, The Andy Warhol Museum; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

Warhol’s Self-Portraits in Drag

Throughout his life, Andy Warhol would step into the camera’s frame and pose as some version of himself. In the early 1960s, a photo-booth strip shows him with his collar turned up and dark shades on, a look reminiscent of the movie stars he idolized. By the 1980s, another version of Warhol emerged. He and close friend Christopher Makos collaborated on a series of images portraying Warhol in drag, as he sometimes dressed for parties. The artist is seen wearing a series of different wigs—short and sassy, dark and mysterious, gray and matronly, long and wild—in a full face of makeup, including deep red lipstick. Most were taken during the same session as those in Makos’ series Altered Image, modeled after Man Ray’s 1920s work with Marcel Duchamp, in which the two artists created a female alter ego named Rrose Sélavy for Duchamp.

A Piece of Carnegie’s Mansion

Andrew Carnegie lived large. His 64-room mansion on New York City’s Upper East Side was evidence of that. Built from 1899 to 1902, it was intentionally spacious and a study of innovative design as the first private residence in the U.S. to have a structural-steel frame. The English Georgian-style building also boasted an extensive garden, electric elevator, and a state-of-the-art heating and cooling system. Part of the house—two copper window surrounds designed by the architectural firm of Babb, Cook & Willard—were incorporated into the design of Carnegie Museum of Art’s Heinz Architectural Center, which opened in 1993 and includes exhibition galleries, offices, a library, and collection storage rooms. To spy the window frames, look up toward the ceiling when entering the galleries from the Hall of Sculpture balcony. Today, the former Carnegie mansion is home to the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum.

PaleoLab

Easily one of the coolest—and most unique—experiences at Carnegie Museum of Natural History is peering inside its fossil preparation laboratory, PaleoLab. It’s a literal window to where scientific preparators, depending on the task, patiently and meticulously clean, chip, scrape, sculpt, or even super-glue together the fossils and fossil replicas of prehistoric behemoths—all while the public curiously looks on. Preparators free fossils from the rocks that encase them and conserve and stabilize them to the point where they can be handled, studied, or displayed. They also reassemble bones from weathered and broken fragments and sculpt replicas of missing fossils to fill gaps in mounted skeletons. They’re continually “working the bones”—from the fossils of a 90-foot-long titanosaur from Argentina to the skeleton of Camptosaurus, which had been half embedded in rock and mounted into a wall panel at the museum for decades before preparators were charged with making it a freestanding, mounted dinosaur for Dinosaurs in Their Time.

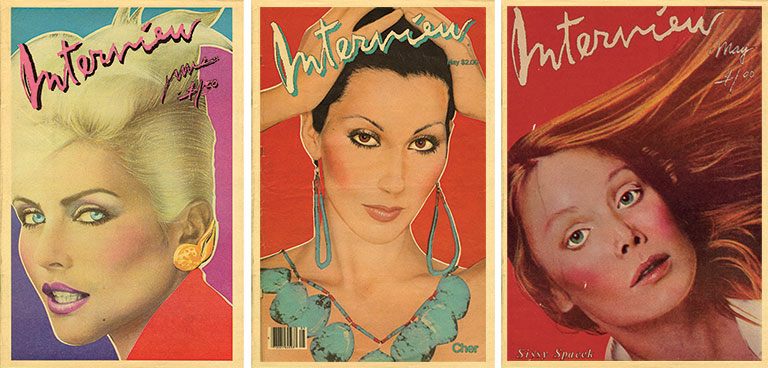

Interview Magazine

Like Andy Warhol himself, Interview magazine, the publication he founded in 1969, was many things all at once: raunchy and insightful, a gossip rag and a think piece, artistic and commercial. The covers did much of the talking. In the beginning, the oversized format featured photos of the likes of Michael Jackson, Grace Jones, and Liza Minnelli airbrushed and colorized to perfection by illustrator Richard Bernstein, who designed a remarkable 189 covers. Inside, the magazine gained fame for its unedited, unfiltered, and tape-recorded celebrity question-and-answer sessions. They “read just like conversations, sometimes boring and trivial,” wrote Mary Harron in Pop Art/Art Pop, “but with the fascination of eavesdropping.” Salvador Dali spoke of his moist sofa; David Bowie about his brother’s mental illness. Dubbed the “Crystal Ball of Pop,” Interview lived on after Warhol’s death, and today The Warhol’s archives house a rare, nearly complete run of the publication. In 2018, with lawsuits filed and bankruptcy declared, it was announced that Interview was shutting down, but it quickly resumed publication under Crystal Ball Media.

The Handiwork of Charles Bowdish

Every day, visitors to Carnegie Science Center’s Miniature Railroad & Village® peek inside the windows at the hustle and bustle of a small-scale general store, blacksmith shop, and other 20th-century Main Street businesses built more than a century ago by the exhibit’s creator, Charles Bowdish. Among his more well-known contributions: the woman walking back and forth in a lit room as she rocks her baby. It turns out that this model home was inspired by his own childhood home, complete with his mom rocking his older brother to sleep on the porch. He also created a crowd favorite—“handstand man,” the death-defying acrobat who does a handstand on a pole high above a turn-of-the-century amusement park, which is a composite of Kennywood, the old Luna Park in North Oakland, and Lakemont Park in Altoona. Patty Everly, the display’s creative caretaker since 1991, is always finding fresh ways to keep the exhibit’s early history and founder alive. Outside of the model of Richardsville Baptist Church, where Bowdish’s parents were married, she’s created a scene where a husband and wife, greeted by family and friends, spill out of the church.

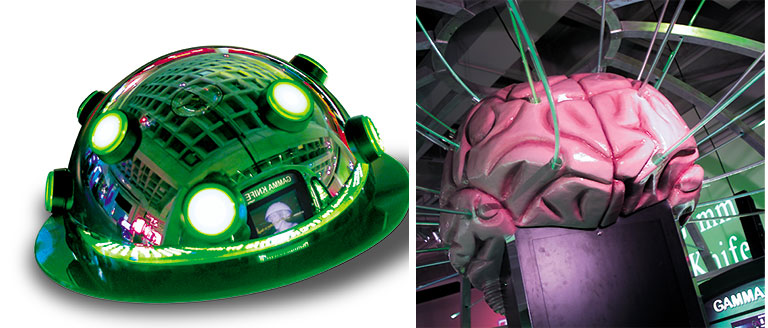

Zap! Surgery Beyond the Cutting Edge

Debuting to much fanfare in the fall of 2000, Zap! Surgery Beyond the Cutting Edge showcased Pittsburgh’s medical community as a leader in high-tech surgery and Carnegie Science Center as an innovator of high-tech exhibitions. Then the only traveling exhibition in the world to detail the trend toward less invasive surgery, it presented complex technologies and the science behind them through unique interactive experiences developed by the Science Center, including a 15-passenger motion simulator that allowed visitors to witness surgical techniques from various points inside the human body. Developed in consultation with University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, it demonstrated how the power of electromagnetic waves, sound waves, and lasers are harnessed to destroy tumors, break up kidney stones, and correct vision. After its stint in Pittsburgh, it went on a national tour to 11 stops.

Ancient Egyptian Sandal

Of the roughly 5,000 ancient Egyptian objects in the care of Carnegie Museum of Natural History, only about 650 are on public view. This single embossed leather sandal, excavated in the Fayûm region of northern Egypt during the Graeco-Roman period (332 BCE–395 CE), arrived at the museum in 1903 by way of the long-standing Egypt Exploration Society and has never been shared publicly. While not visible in this image, the bottom of the sandal is slightly worn and coming apart—a welcome discovery for museum researchers because it allows a closer inspection of the craftsmanship and construction techniques; how the strap is braided and attached to its base, for example. The artifact also “gives us a glimpse of what was in fashion and what people were actually wearing” some 2,300 years ago, says museum Egyptologist Lisa Haney, “because the visual record at that time often includes idealized representations,” such as men frequently depicted without shirts, even though the reality is that it can get very cold at night in the desert.

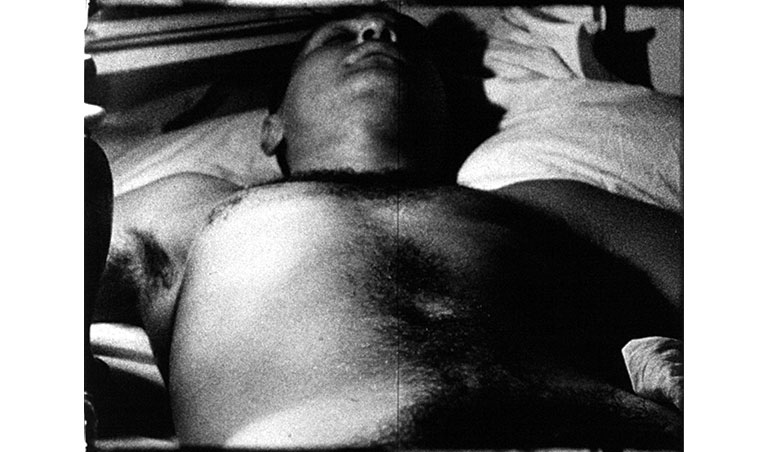

Sleep by Andy Warhol

When Andy Warhol made his first film in 1963, he aimed his 16 mm Bolex camera squarely at then-boyfriend John Giorno. But Giorno, a poet and performance artist, doesn’t play a character or even speak in the black-and-white production aptly titled Sleep. Arguably Warhol’s most famous film, it’s 5 hours and 21 minutes of Giorno’s upper body and pillow-framed face. The avant-garde creation has been called an anti-film, but the strange appeal of a sleeping Giorno has endured. It propelled the compulsively prolific Warhol into a new medium as he went on to create another 300 films and thousands of other fragments stored on videotapes.

Giant Game of Operation

Inside Carnegie Science Center’s Highmark SportsWorks®, young explorers can challenge themselves to “remove and repair” body parts linked to the 10 most common sports injuries by way of an oversized version of the classic childhood game of Operation. It’s fun for kids and nostalgic for parents, while also teaching them something about basic human anatomy and common ailments, such as a groin pull, sore neck muscle, and shin splints—the latter illustrated in the game by a giant rubber band.

The Two Faces of Prudence

Tucked away among the 140 plaster casts of architectural treasures in Carnegie Museum of Art’s Hall of Architecture is the spectacular tomb of Francis II, the Duke of Brittany. It includes an intriguing feature that can be easy to miss: a figure with two faces. The original tomb, made of Carrara marble in 1507 by sculptor Michel Colombe, was located in Nantes Cathedral in France. A masterpiece of Renaissance sculpture, it was commissioned by Anne of Brittany, the queen of France and daughter of Francis and his second wife, Margaret of Foix, who is shown lying beside Francis. The duke had hoped the cathedral would be his final resting place with his first wife, Margaret of Brittany, and the tomb actually houses Francis and both wives, though only Anne’s mother is depicted. At the tomb’s four corners stand four figures, each representing one of the cardinal virtues: courage, justice, temperance, and prudence. Prudence has two faces: at the back is an old man, said to be the sculptor, implying the wisdom of the past; at the front is a young woman looking to the future, who holds in her hands both a compass and a mirror.

Childe Hassam, Fifth Avenue in Winter, c. 1892, Carnegie Museum of Art

Fifth Avenue in Winter

Working as a wood engraver and illustrator, artist Childe Hassam (1859–1935) fought against labels as critics looked at his work through the lens of a singular style. It was a battle he lost. Today, Hassam is known as a pioneer of American Impressionism, and was unique for often depicting burgeoning city scenes, which he captured with affection and originality. A frequent participant in the early Carnegie Internationals, Hassam had more than 90 of his paintings displayed at Carnegie Museum of Art over nearly four decades and the artist served on the exhibition’s award jury multiple times. It was quite fitting that in 1900, the museum was the first American institution to purchase one of Hassam’s paintings: his 1892 oil on canvas titled Fifth Avenue in Winter, a visitor favorite featuring horse-drawn carriages and pedestrians making their way along the snow-covered New York City street.

Jesus statue, painted by Andy Warhol between 1938 and 1941, Courtesy of Jeffrey Warhola

Statue of Jesus by Andy Warhol

Not long after Andy Warhol’s passing, staff at The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts (and, upon its founding in 1994, The Andy Warhol Museum) started sorting through and cataloging the many things Warhol left behind, including his 610 Time Capsules. Most of the Time Capsules are cardboard boxes filled with newspaper clippings, day planners, bills, ticket stubs, handwritten letters—life’s detritus. Stashed inside them is no shortage of material clues of the artist’s Byzantine Catholic influences, including family prayer books and prayer cards, souvenirs from Pope Paul VI’s 1965 visit to New York City, and mementos from Warhol’s 1980 visit to the Vatican, where he met Pope John Paul II in St. Peter’s Square. Many of these deeply personal items were on display for the first time in The Warhol’s 2019 exhibition Andy Warhol: Revelation, which explored the connection between Catholicism and the artist’s body of work. A very special addition, on loan from the John Warhola family, was this chalkware plaster statue of Jesus that Warhol painted when he was between 10 and 13 years old, taking great care to detail the crucifixion wounds on the hands of Christ and color the Sacred Heart a deep red.

Ivory Eagle

A majestic, life-size ivory eagle that H.J. Heinz purchased in Japan a century ago was returned to its original splendor in 2013 thanks to Carnegie Museum of Natural History conservators, work that took two months and occurred while curious museumgoers looked on. The Pittsburgh ketchup magnate bought the bird by an unknown artist in Yokohama in 1913 during one of several trips he made to China and Japan. When the sculpture and its custom case, together weighing 550 pounds, arrived at the museum in 1913, Assistant Director Douglas Stewart deemed it “the finest specimen of its kind in the world.” It was valued then at $5,000 and was a favorite of visitors until it went off view in the 1990s. It was restored in preparation for a Carnegie Museum of Art exhibition featuring both ivory sculptures and Japanese woodblock prints, many collected and donated to the museums by Heinz. With its 48-inch wingspan and hundreds of feathers, some the size of a quarter and the length of a dinner fork, the ivory eagle remains on view in a prominent spot at the base of the Oakland complex’s Grand Staircase. Conservators removed from it mostly sooty air pollution that had accumulated during Pittsburgh’s industrial era.

Sticky Fingers by the Rolling Stones, 1971; album design by Andy Warhol, 1972

Sticky Fingers Cover Design

There was a time when nearly everyone owned a Warhol. The zippable zipper on the cover of the Rolling Stones’ Sticky Fingers album helped make it one of the bestselling albums of its day while also becoming one of the most iconic images of 1970s rock. The cover was a collaboration between Andy Warhol and Craig Braun, who was known in the heyday of vinyl records as a designer of sophisticated cover packages, starting with the 1967 Velvet Underground & Nico LP adorned with Warhol’s famous banana print, which could be peeled to reveal a suggestive pink banana underneath. (Braun, not Warhol, gets credit for the idea of a working zipper on the Stones’ cover.) To scores of fans, Warhol came into view not as the creator of Campbell’s Soup Cans or Brillo Boxes but as part of music history.

Fruit and Other Things

Before it was known as the Carnegie International and curators traveled the globe in search of talent, artists would submit their work in hopes of being accepted into Carnegie Museum of Art’s Annual Exhibition. For most, those hopes were dashed. From 1896 to 1931, the museum sent out 10,632 rejection notices. After discovering that the title of each rebuffed work of art lives on in meticulously kept archival records at the museum (no images exist), 2018 Carnegie International participating artists Lenka Clayton and Jon Rubin set out to replace the sting of rejection with the joy of redemption. Their 23-week performance piece dubbed Fruit and Other Things in honor of one of the titles that didn’t make the cut employed a series of calligraphers to set up shop in the museum’s Forum Gallery. While visitors looked on, the artisans skillfully traced each of the 10,632 titles, in alphabetical order, onto heavy stock paper. Once the ink dried, each hand-lettered text painting was slipped into a frame on the gallery walls—each title at last exhibited as part of the prestigious exhibition. And instead of being forever relegated to the annals of history, every title—from A Bacchante to Zinnias—found new life as museumgoers were invited to take one home, forming a new community of 10,632 art collectors. Check out fruitandotherthings.com to see where the paintings hang today.

Lion Attacking a Dromedary

One of Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s oldest dioramas, Lion Attacking a Dromedary depicts a figure riding on a camel being attacked by a male lion; a female lion lies nearby, lifeless. It’s a brutal scene. Created by French taxidermists Jules and Èdouard Verreaux for the 1867 Paris International Exposition, it was on view at the American Museum of Natural History for decades before it fell out of favor for being too strong on theatrics. The New York museum had plans to discard it before selling it to Carnegie Museum in 1898. Well over a century later, museum curators and educators are engaging visitors in discussions about what’s depicted in the diorama: the lion—a symbol of imperial power—pouncing on a person of color, which reinforces colonialist views and minimizes deeply rooted violence; and the clothing in the display, which inaccurately groups a number of distinct North African cultures together, reinforcing stereotypes. The museum also plans to remove the figure’s head, which is sculpted around the skull of an unidentified human being, and will place the remains in a sanctuary space in the museum’s care.

Receive more stories in your email

Sign upTags:

Where Art & Science Meet