At school districts across the country, the pandemic has dealt students one disappointment after another. No school dances. Few spectators at football games. Canceled musicals and nixed field trips. In light of all the letdowns, students in the gifted program at Penn-Trafford High School held on to one hope—please, let the Chain Reaction Contraption Contest at Carnegie Science Center go ahead.

“Are they going to have it this year?” students repeatedly asked teacher Christina Wukich throughout September.

To their delight, the Science Center moved forward with the popular competition that challenges small teams of high schoolers to create the most complicated series of physics feats possible to complete one simple task in 20 steps or more—think wacky Rube Goldberg machine. The contest attracts schools from all over the region.

The Science Center’s annual Chain Reaction Contraption Contest always inspires students to think big while applying science to solve problems. This year, despite all of its challenges, was no different. Photo: Renee Rosensteel

Science Center educators worked with area teachers to make sure the December event was safe, without forgoing any of the drama of the zany and elaborate designs that the teens dream up. Instead of traveling to the North Shore museum to present live at the competition, which is co-organized by the Engineers’ Society of Western Pennsylvania and Westinghouse Electric Company, students presented videos of their creations. They also sent their design plans to a panel of judges, who did their work virtually as well.

“The fact that the Science Center is offering the program virtually is huge,” Wukich says. “We had this barrier and they adapted. They’re not waiting for the coronavirus to go away. They understand that in-person school may be here today but not tomorrow. The Science Center has been fantastic about helping us.”

Because the Westmoreland County school district is currently operating on a hybrid schedule, the students worked on their contraptions in school, virtually, and at each other’s homes, says Wukich.

“The fact that the Science Center is offering the program virtually is huge. We had this barrier and they adapted.”

– Christina Wukich, Educator at Penn-Trafford High School

Continuing the contest in a new format is just one of the myriad of ways that educators at the four Carnegie Museums are working creatively with area K–12 teachers to help keep students inspired and teachers supported during an extraordinarily difficult and exhausting school year.

Listening to teachers

During the summer, museum educators held virtual focus groups, conducted online surveys, and in some cases talked one-on-one by phone with teachers hailing from urban and suburban and public and private schools about their needs in an ever-changing environment. One big takeaway: With no field trips, teachers are looking for ways they can bring the museum to their classrooms virtually.

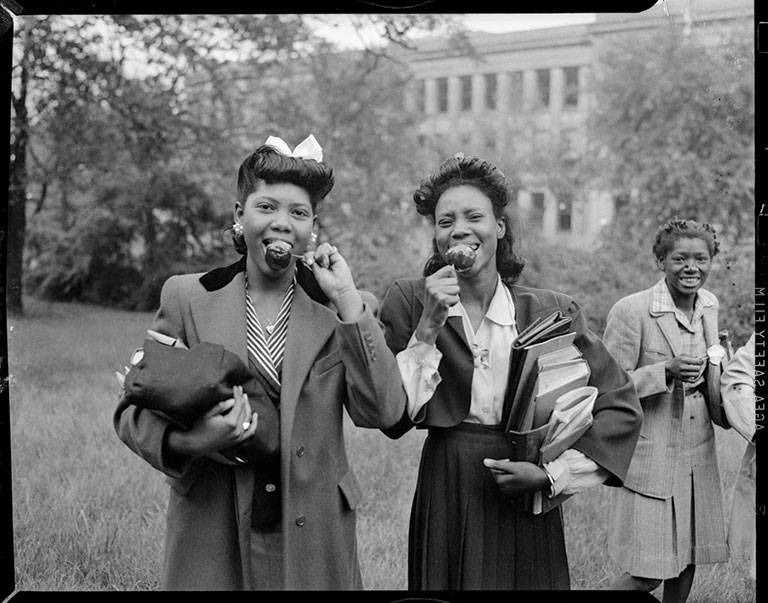

For example, grade-schoolers at Pittsburgh Public Schools can’t visit Carnegie Museum of Art to experience the new gallery featuring the work of photojournalist Charles “Teenie” Harris, whose photographs capture the everyday Black experience in Pittsburgh from 1935 to 1975. So their teachers asked for alternate ways to make this valuable connection. Starting in December, Harris’ images—along with freshly developed lessons that, as requested by teachers, encourage conversation, close looking, and critical thinking—will travel to the students by way of short videos.

“We’re very interested in Teenie Harris and celebrating Black life historically,” says Nina Unitas, the coordinator of visual arts and design at Pittsburgh Public Schools. “[This project] will help give faculty a space to talk about race and the role it plays in their lives and the lives of the children they are teaching.”

Charles “Teenie” Harris, ca. 1938–1945, Carnegie Museum of Art; Heinz Family Fund

Because Harris’ work garnered the most interest among all teachers, Museum of Art educators are using the Teenie Harris Archive to teach all ages—from kindergarteners to high school students—four elements of Black history in Pittsburgh. The topics of social groups, access and opportunity, and intersectionality—the idea that most people live at the intersection of many identity categories, from race and ethnicity to age and socioeconomic status—match up with those highlighted in the new Teenie Harris gallery.

An additional theme, Black change agents, features positive influencers in the Pittsburgh region. One image from the ’50s shows a crossing guard guiding a row of kids crossing Frankstown Avenue in Homewood, the girls wearing full skirts and white anklet socks. Another shows a woman in pants leaning against Kay’s Valet Shoppe, a cleaning, pressing, and alterations shop on Wylie Avenue in the Hill District. “A woman wearing pants in the 1940s was quite shocking,” says Meg Scanlon, the museum’s manager of K–12 school student programs. “We don’t actually know if she is Kay or not.” It’s an image that can open up multiple conversations, including the fact that living in a world of institutional oppression means you can flourish as a Black, female business owner, and still face discrimination.

At the request of teachers, the materials will be unmediated so that they can be shared with students who are learning from home or in the classroom. And the videos will be three to five minutes in length to increase flexibility of use and prevent students from getting screen fatigue, says Scanlon.

“[This project] will help give faculty a space to talk about race and the role it plays in their lives and the lives of the children they are teaching.”

– Nina Unitas, coordinator of visual arts and design, Pittsburgh Public Schools

Deborah Lieberman, an art teacher at Pittsburgh Linden PreK–5, says she’s eager to share the life’s work of Harris with her young art students. “He was the One-Shot wonder,” says Lieberman, referring to Harris’ reputation of capturing his subjects in a single take. “It’s important for the students to see themselves reflected in art. It allows them to imagine what it would be like to have their own art out in the world. To think about what they want to say, and what it would look like.”

She’s planning an activity that encourages students to take photographs around their neighborhoods or inside their homes and then upload them to a virtual art gallery. “They can take photos of everyday situations—their family at dinner or playing games. They can create their own archives.”

Based on feedback from the focus groups, and made possible with support from The Grable Foundation and First National Bank, the Museum of Art is also developing new lessons in four additional subject areas—migration, looking and learning, the power of art, and art and literacy—all topics Unitas says are of interest to Pittsburgh Public Schools. They’ll be designed for teachers in various disciplines, with different prompts available for different grades and areas of interest. Students in kindergarten through second grade may watch a video and explore a word bank, while older elementary students may get a journal prompt and vocabulary list.

For Lieberman, the ongoing collaboration with the museum and access to its collections—even remotely—is a gift. “There is so much valuable knowledge and information the museum educators can bring to the table and elevate what I’m teaching.”

Hands-on learning—from home

For many area schoolchildren, walking among the hulking dinosaurs at Carnegie Museum of Natural History during a school field trip is a highlight of elementary school. So, too, is the popular classroom activity that follows, which lets kids wrap a replica T. rex or Triceratops fossil in plaster and burlap, the way a paleontologist would, and then take it home as a souvenir.

But how do you replicate popular hands-on experiences virtually?

Museum of Natural History educators have created a virtual field trip of Dinosaur Armor that allows students and teachers to take a live tour of the new exhibition at a set time and date, followed by access to a step-by-step video of the making of a fossil cast, an interactive activity that can easily be done at home.

“You probably don’t have the tools to make a replica T. rex claw,” says Breann Thompson, assistant director of education programs at the Museum of Natural History. “So we put together a video that shows you how to do the process with a toy dinosaur or a chicken bone leftover from dinner. We encourage people to make it with flour and water.”

Not only has the program already proved popular among school districts in western Pennsylvania, requests have come from as far away as Qatar. “Not everyone who wanted to see the exhibition could just hop on a flight,” says Thompson. “Now they can see it without leaving home.”

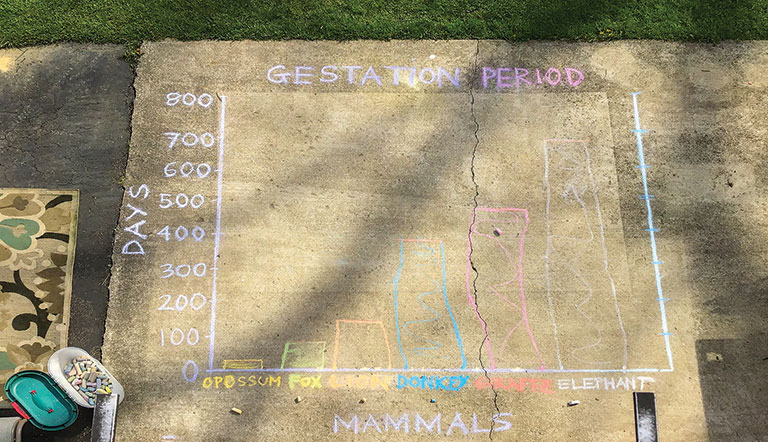

North Allegheny science teacher Christian Shane created backyard science videos inspired by real objects he borrowed from Carnegie Museum of Natural History, including a variety of animal skulls. He also got creative with sidewalk chalk to help students understand how an animal’s size relates to the length of its gestation period.

Other local teachers like Christian Shane are taking advantage of the museum’s Educator Loan Program. In March, Shane borrowed multiple science kits that included skulls of various mammals for his science classes at Ingomar Middle School in the North Allegheny School District.

“I want [students] to notice things where they live that relate to what we’re covering in our remote lessons.”

– North Allegheny science teacher Christian Shane

He was prepared to study the fossils hands-on alongside his seventh graders, but school closings shelved those plans and many others. So, the science teacher got creative, making YouTube videos outdoors at home. His backyard science lessons presented the bones of a muskrat and asked his students to identify them based on structure and size. Another video highlighting bones and biomes featured museum skulls of 10 animals, including a rabbit, woodchuck, black bear, and even a polar bear. He contacted museum educator Patrick McShea to fact check the science before showing the videos to his class.

“During the warmer months, I was getting the students outside,” he says, noting the importance of young people making detailed observations of the natural world. “I want them to notice things where they live that relate to what we’re covering in our remote lessons.”

Pop art for all

Shortly after schools closed in March, artist-educators at The Andy Warhol Museum launched Making It, an award-winning series of short educational videos featuring the techniques Andy Warhol used on his road trip to Pop art superstardom. Available for free on the museum’s YouTube channel and created with a DIY sensibility, Warhol’s methods of radical cropping, stamping, book binding, and the blotted line technique are adapted for home use by families or K–12 classes.

“It’s fun for all ages, from elementary school to high school,” says Nicole Dezelon, associate director of learning at The Warhol. “We’ve seen parents, teachers, and kiddos at home get really creative with some of the materials. Teachers told us they were key to helping them pivot quickly to online teaching since they could upload the demonstration videos and also use our online lesson plans and PowerPoints.”

Students participate in a live virtual field trip at The Warhol.

Also new, popular, and created in response to visitor and teacher requests over many years: the museum is now selling and shipping limited-edition subscription boxes stuffed with art supplies, ready-made activities, links to media, and select products from The Warhol Store. “Teachers can use them when and how they want, which is especially key right now,” says Dezelon. Each themed box guides students in different artmaking adventures—from making their own rubber stamps like the ones Warhol used in his early illustrations as a commercial artist, to turning everyday objects into works of art, much like Warhol elevated the lowly Campbell’s Soup can into a Pop masterpiece.

When schools closed in March, it was the museum’s online time capsule activity that proved especially meaningful to Kristen Johnson, a teacher at Benjamin Franklin and Memorial Elementary Schools in Bethel Park. It’s inspired by Warhol’s serial work of art consisting of 610 cardboard boxes that he filled to the brim with the detritus of his life.

“It’s a moment in time that’s unique. Just as we’ll always remember when 9/11 happened, these kids will always remember the shutdown,” says Johnson. To mark the occasion, students stamped their handprints onto paper, wrote about their feelings, and collected trinkets—such as a dog’s favorite toy or a Pokémon card—and stashed them away to be opened in 20 years.

“Maybe next we’ll try the art boxes,” says Johnson, who usually takes her fourth graders to The Warhol to silkscreen T-shirts, the highlight of a class unit on Pop art.

Reaching more learners

Besides holding the Chain Reaction Contraption Contest virtually, two of the Science Center’s most popular annual STEM field trips—SciTech and ChemFest—also went digital, along with its Science on the Road assembly programs.

“Instead of a gymnasium full of students watching a presenter on a stage doing demos, we’re now on our own stage within the Science Center,” says Lisa Herrmann, senior director of STEM education at the North Shore museum. “We present it live, tailoring it to the grade level of the audience. It’s not pre-recorded. It feels interactive. The presenter might suggest, ‘Imagine what would happen if I did it this way or that way.’ The students will see real-time variations, engaging them in an inquiry process.”

For example, in SolarQuest, a live presentation about how the sun and Earth are interconnected, a science educator puts a blowtorch to a hydrogen balloon, setting off an explosion that ends in a ball of fire. Interspersed with live science are pre-recorded video clips, including one of hometown hero Mike Fincke, a NASA astronaut who grew up dreaming about the cosmos in Buhl Planetarium, who talks about the wonder of seeing Earth from space. He’s also shown spinning a weightless Terrible Towel from the International Space Station.

For all the challenges of virtual science, there are some advantages to the brave new world of reimagining museum favorites. “There’s no travel time. We can now deliver shows back-to-back or even simultaneously, so we have the potential to reach more classrooms,” says Herrmann. “And now our science has a broader international reach. That’s one of the big pluses of the challenging moment we find ourselves living in.”

Receive more stories in your email

Sign up