As an artist and a human living through 2020, this year has pushed me to find a balance between new and old ways of thinking and doing. I use photography, filmmaking, and archival research to tell stories about everyday Black experiences, with a particular focus on how the past shapes the present. Isolated during quarantine, I used photos and image-based media I had at home to venture into collage for the first time. The resulting series, titled City on a Hill, helped me find a new way to articulate my feelings about the political and social fallout our society is experiencing today. It also helped me explore my hope for what a better future can entail.

The experience of producing work during such an intense time made me reflect on the larger tradition of Black women making art in America. Today’s challenges may be acute, but they’re not new. We’ve always had to create under difficult circumstances. Society has long consumed the culture Black women produce while in turn oppressing, ignoring, and erasing us. Still, we’ve found a sense of joy and purpose in our work. I believe it’s critical for the people who engage with our work to see us not just for what we make, but for who we are and why we make it.

As such, I wanted to use this platform to connect with another Black woman artist. atiya jones is a Brooklyn-raised, Pittsburgh-based, multidisciplinary artist I deeply admire. Our backgrounds overlap in several places, including growing up in households full of art, working in both the public realm and the studio, and exploring issues of migration and gentrification in our work. This published portion of our conversation picks up after we discussed writing our own rules, and tackling learning to repurpose fear. As it progresses, we share our experiences leading up to and within this critical moment as Black women living and making art in Pittsburgh.

Njaimeh: I’m curious how ambition, and how moving through your fears, manifests itself in your work?

atiya: I think that that fear has shown up in the things that I have said yes to. A lot of the projects that I’ve completed in the last four years, I had never done anything like it. I said yes, and figured it out. The breadth of the things that I make don’t necessarily fit into a box, and that’s a part of what I’ve accepted about myself. Getting to that point has been the work, you know … to realize that no one can do what I do.

Njaimeh: I think of that also in the context of being a Black woman. This realization that there’s so much that you embody. I think of the ancestors and how many people sacrificed for us to be here. I can walk with a little bit of confidence [and] I can move through my fears because I know that I have all this behind me, and all this in me.

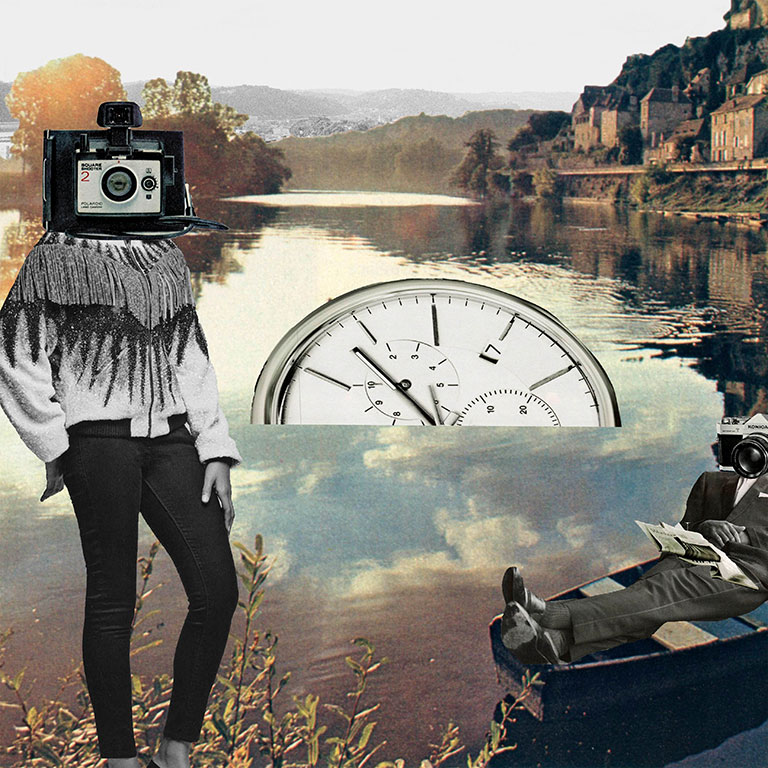

Njaimeh Njie, Down Time, 2020

atiya jones, it will not be my hands that hold you up, 2018

atiya: But also … we have so much information—familial, historical information—that is lost. We lose that very confidence because we don’t know who’s behind us. It’s the thing that I have struggled deeply with because I don’t know my family’s history, really. I felt like a tree without roots for very many years.

Njaimeh: I’m not privy to the details of my ancestors’ lives [so] I think it’s more of a subconscious thing for me. The fact that I’m still here means that Black people —particularly Black women in my family—had to survive and pass something down. We could very well not be here [with] all the things that we’ve had to endure.

atiya: So you just said, “The fact that I’m still here,” which implies that the other option is death. I think about dying all the time. It’s not like in a goth way, but the fact that I’m alive, you know. Especially right now … in a pandemic. I’m deep in work, while I should have—could have—been deeply in mourning for so many things. And so to live in a world that is blatantly showing my lack of value … I’m constantly having to reestablish my own faith in my own importance, and the importance of people who look like me. And I have to participate in this self-aggrandizing behavior because if I don’t, I don’t know who will.

A participant completes the phrase “My Black is …” as part of atiya jones’ public art installation produced for Pantene/Head & Shoulders at the Afropunk Festival in 2018.

“I think of the ancestors and how many people sacrificed for us to be here. I can walk with a little bit of confidence [and] I can move through my fears because I know that I have all this behind me, and all this in me.” – Njaimeh Njie

The Village, completed in 2019, is one of four public art installations included in Homecoming: Hill District, USA, Njaimeh Njie’s public art project and digital archive exploring a resident-centered history of the Hill District.

Njaimeh: A few things that you said triggered a dual question for me. In your practice, what do you feel like you’re remembering? What are some things that you’re calling back to that manifest in your work; but on the flip side, what are you interested in preserving?

atiya: Most immediately, I’m remembering myself. The more I think about it, I think that it is a self-serving practice. And then I am reminded that what serves me, serves others. It’s a lot of self-remembrance because I give myself often to many things and many people, but when I’m making art, I’m making this for me. Maybe we’re going to share it. Maybe you can have it afterwards. But while it’s on my table, it’s my food.

Njaimeh: Yeah. Whew.

atiya: And in regards to preservation, especially with public work. I create public work for folks who don’t have, or feel like they don’t have, access to artwork. I’m preserving space for art to be consumed ad hoc. I want it to be seen. I don’t want to be ignored.

In atiya jones’ image before the storm, created in 2018, a group of Black women embrace for a photo before breaking into a group twerk.

“In relation to my experience as a Black woman, to be bold is a protest. To be seen is a protest. I exist to protest and I protest with my own Black joy. I got to go live because what I’ve learned—what I continue to learn—is that these moments are precious. And every day I have to select living how I want to be remembered.” – atiya jones

The 2018 image titled The Glue, part of Njaimeh Njie’s On the Daily series, captures a warm moment between Tamanika Howze and Bekezela Mguni.

Njaimeh: When I started taking pictures I was OK to put other people’s stories to the forefront. I was [thinking] what can I present of the world, instead of, how am I actually participating and showing up in the world. I think I’m starting to break that barrier down a little bit, but it’s really encouraging … and lights a fire under me to hear you say [you] want to be seen.

atiya: I think, in the process of developing my line work, I quickly understood that I was inventing my own language at a time in which I didn’t have one. [Over] time my work has only gotten bigger, and I have no interest in minimizing. So I think about expansion a lot. I think about growing, I think about not being made small by anyone. In relation to my experience as a Black woman, to be bold is a protest. To be seen is a protest. I exist to protest and I protest with my own Black joy. I got to go live because what I’ve learned—what I continue to learn—is that these moments are precious. And every day I have to select living how I want to be remembered.

Njaimeh: You talking about creating this language for yourself speaks to me, because it’s my constant goal to try to find my own voice, and try to find my own aesthetic. To find those moments that click for me, where it feels like my brain and my heart and my gut are working [together] to make this image that articulates something that I want to say in the world, in a way that other people can pick up, understand, or feel something.

atiya: It reminds me of the phrase, “to sit in your power.” Just understanding that we can be all types of people … we got everything. We can be everything. We are everything, you know.

Njaimeh: I think there’s something tangible that clicks when you see yourself. And when there’s an acknowledgement that you exist in the world, that is almost like a little bit of validation to take up more space.

atiya: The more we feel like we can come into ourselves and grow from there.

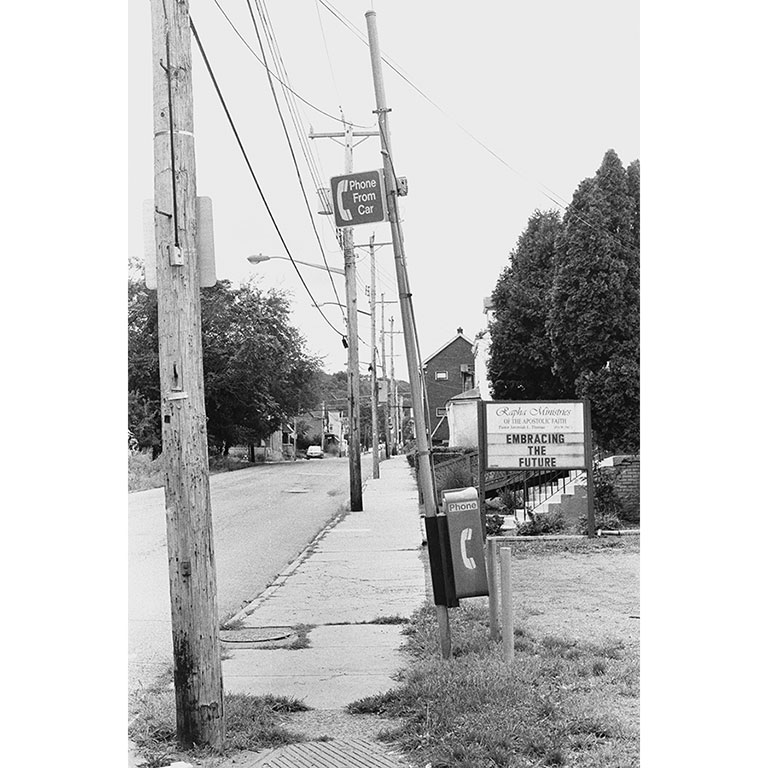

Push and Pull, part of Njaimeh Njie’s On the Daily series, documents the everyday tension between old and new within a rapidly changing city.

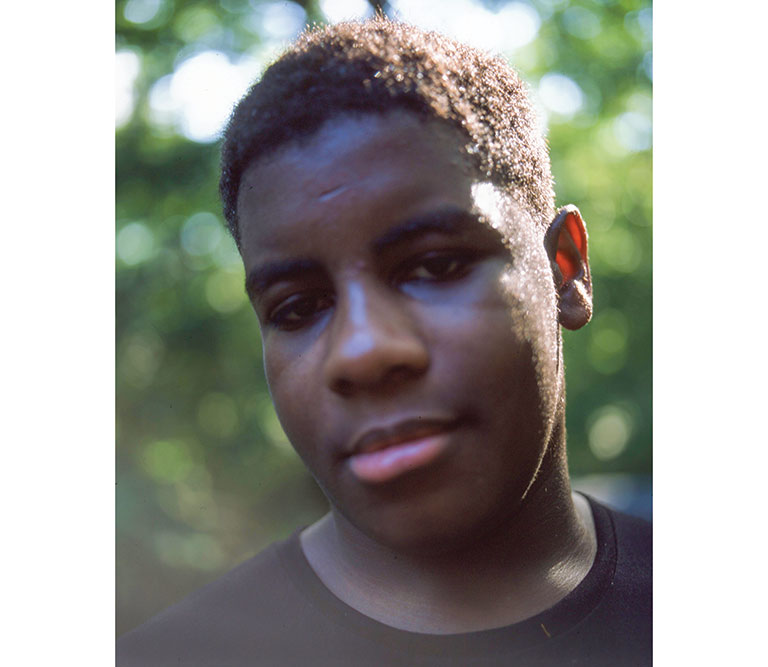

In atiya jones’ 2020 portrait the future, the artist photographed her nephew Elijah after cutting his hair on his 15th birthday.

Njaimeh: That’s why it’s so important to hold space for the work, right? Black women making art is incredibly important. That’s a way that we make our imprint on the world, and share ourselves with others, and help each other keep going.

atiya: The more I’m starting to see other Black photographers work in the world, the more that I feel encouraged, because honestly I have never identified as a photographer until about two years ago. Even though this is what I’ve been doing longer than any other part of my practice.

Njaimeh: Yeah. Sometimes I wonder if the specificity of naming—[saying] I’m a photographer, I’m a blank—if that’s a way of excluding people. But I [also] think there can be power in articulating [that] as a Black woman, here’s a thing that I specialize in. I’m present in this arena too, and you need to know that.

atiya: I don’t struggle with definition because it’s not worth my time. I create what’s necessary. I’m not going to define myself because you want me to. I think the greatest discovery I’ve made in regards to the art world is the [term] multidisciplinary artist. Then I tell [folks] what mediums I work in. So far I have not come across anything that I can’t do. And when I get there, I’ll let them know. But I don’t fit in a box. And it’s the most comfortable place I’ve ever been.

Above left: Njaimeh Njie Photo: Zeal Eva

Above right, atiya jones Photo: atiya jones