Select objects by thumbnail or filter objects

Dinosaur Hall’s T. rex Mural

For decades, visitors flocked to Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s original Dinosaur Hall to see its resident VIPs—Diplodocus carnegii, Apatosaurus louisae, and Tyrannosaurus rex. They left with a dark and foreboding image baked into their brains, painted in 1950 by the museum’s chief artist, Ottmar von Fuehrer. The floor-to-ceiling mural took the Carnegie Tech-trained artist months to complete, and museum visitors got to watch as the depiction of the fierce creature took shape. Part T. rex, part Godzilla, the lumbering dinosaur was based on the science of the day. Later that century, scientists learned that T. rex moved with its back held almost horizontal, with its powerful jaws just a few feet above eye level and its tail raised well off the ground. So, von Fuehrer’s mural had to go. But his work is still on view today—from the painting of Mt. Rainier in the Hall of Botany to the murals in the Hall of North American Wildlife’s dioramas.

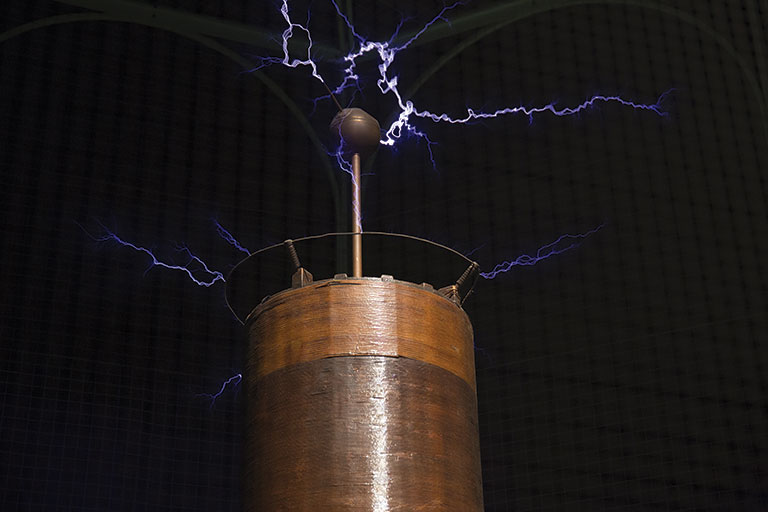

The Tesla Coil

Lightning strikes a few times nearly every day at Carnegie Science Center, thanks to the fan-favorite Tesla coil, named after inventor Nikola Tesla. Visitors to Works Theater learn how Tesla’s invention, built in 1891, would go on to find applications in early radio-transmission antennae, television picture tubes, and sodium street lamps. But they also learn that the Science Center’s 10-foot-high creation is one of the country’s largest and oldest amateur-made Tesla coils still in operation today. Pittsburgh teenager George Kaufman constructed it in 1911 in the attic of his family’s Ben Avon home. It took him a year and $125 of his own money, not to mention the ire of neighbors who suffered power-grid failures due to the 1 million volts of ungrounded electricity it generated. Kaufman went on to earn a degree in electrical engineering from what’s now Carnegie Mellon University, and became chief electrical engineer for J&L Steel, where he earned more than 100 patents. In 1950, he donated his Tesla coil to Buhl Planetarium, where its special brand of homemade lightning wowed visitors for decades before finding a new home at the Science Center in 1991.

The Women’s Suffrage Parade, in Miniature

On May 2, 1914, courageous women took to the streets of Pittsburgh in support of the era’s most controversial topic—a woman’s right to vote. Eighty-one years later, in 1995, Carnegie Science Center honored them by making their parade part of the Miniature Railroad & Village’s® magical world. Model makers drew their inspiration from newspaper accounts and parade handouts, making dozens of tiny figures dressed in colorful period clothing. Leading the way is Julian “Boss of the Road” Kennedy, followed by Jennie “Liberty Bell” Bradley Roessing, driving the same car she drove to each of Pennsylvania’s 67 counties, lobbying for the cause. According to the Pittsburgh Daily Post, “Race, creed and social standing were eliminated in the common cause,” as representatives from the National Association of Colored Women, Chatham University, and the Boy Scouts, among other groups, joined the march.

Steamship Trunk

Andy Warhol collected everything from Fiestaware to dental molds to art deco. His 610 Time Capsules are his largest collecting project, in which he stored source material for his artwork as well as odds and ends from his daily life. In this spirit, The Warhol’s education team, in partnership with local immigrant families, developed Community Time Capsules to celebrate Pittsburgh’s rich cultural heritage. Each is an online collection of personal and historical objects that captures the culture and stories of some of the region’s immigrant communities. The Warhol photographed hundreds of items for each Community Time Capsule, and the compilations are part of the museum’s online curriculum that uses Warhol’s life and practice to teach lessons across the humanities. This wood and leather wardrobe trunk puts a spotlight on three generations of the Cavaliere family, who used it to pack their previous lives for their transatlantic travels between Italy and the United States.

A Dinosaur for Pittsburgh

Andrew Carnegie’s intense interest in prehistoric buried treasure began in 1898 when he spied an article in a New York newspaper about a University of Wyoming fossil collector who had stumbled across the ancient remains of the “most colossal animal ever on Earth.” Legend has it that Carnegie sent the clipping with a $10,000 check to Museum Director William J. Holland with the directive to “buy this for Pittsburgh.” The reality is that the check came later. First came a tussle between the university and Holland’s team to remove the fossils. After no additional bones were discovered at the site, Carnegie’s bone hunters moved some 20 miles away to Sheep Creek, Wyoming, where, in July 1899, they found a nearly complete skeleton of a gigantic, long-necked sauropod dinosaur. It would take all of 130 crates to transport the bones of the 85-foot-long giant Diplodocus carnegii—named after its financier—to Pittsburgh via boxcar. Once assembled, Dippy, as the behemoth is now affectionately known, was the star of Pittsburgh’s newly built 1907 Dinosaur Hall.

Robert S. Duncanson, American Landscape, 1852, Carnegie Museum of Art; Heinz Family Fund

American Landscape by Robert S. Duncanson

While we don’t know its exact location, this pastoral scene caught Robert S. Duncanson’s eye shortly after the artist visited Pittsburgh in July 1852. It was still early in his career, before he became the first African American artist to garner an international reputation and the title of “the greatest landscape painter in the West.” Duncanson was in Pittsburgh during a tour of his first historical landscape, The Garden of Eden. He would eventually give that monumental painting to the Rev. Charles Avery, a white minister and philanthropist who was a member of Pittsburgh’s Underground Railroad, “for his generosity and friendship” toward African Americans. Duncanson’s gift was in recognition of Avery’s 1849 founding of the Allegheny Institute, the first college for African Americans in Allegheny County. Acquired by Carnegie Museum of Art in 2018, American Landscape is currently on view in A Pittsburgh Anthology.

Victory, from the Lakota’s Perspective

On June 25, 1876, Lt. Col. George Custer and his troops confronted the Northern Plains Indians, who were defending their right to their land, in the Battle of the Little Bighorn—known to the Lakota and other Plains Indians as the Battle of the Greasy Grass. Custer and more than 200 soldiers died in the conflict now known as Custer’s Last Stand. This beaded antelope hide illustrates the victory of Lakota Sioux and Cheyenne warriors over U.S. federal troops, as told from a Lakota perspective. An unknown artist made it in the early 1990s in the style of 19th-century ledger art. At the time, it was uncommon for commercial work to depict the Indigenous point of view. In the lower right quadrant, there’s a figure in a maroon top with white dots (representing elk teeth/hunting prowess) believed to be a woman warrior, a respected individual within Plains tribes. Installed in the Alcoa Foundation Hall of American Indians in 2018, the hide was donated to the Museum of Natural History by Lester Becker in memory of his late wife, Joan Becker, a retired librarian and friend of the museum who volunteered in the anthropology department for 13 years.

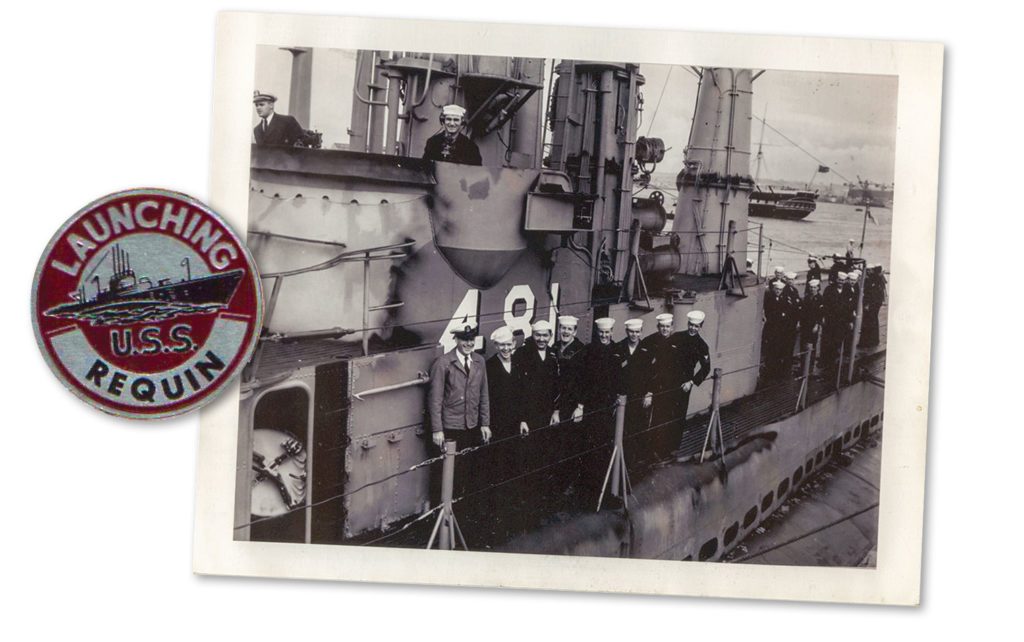

USS Requin crew in front of the original sail configuration, 1946.

USS Requin (SS-481)

The USS Requin has been moored on Carnegie Science Center’s Ohio River shoreline since 1990, a floating technology and history lesson. In active service from 1945 to 1968, it once carried a crew of up to 80 sailors and supported both defensive and scientific missions, some of them still classified. Launched on January 1, 1945, from Portsmouth Navy Shipyard in New Hampshire, it quickly earned the nickname Galloping Ghost of the East Coast for its Cold War adventures policing the Eastern Seaboard. Its first commander was Slade Deville Cutter, a 6-foot-4-inch captain with four Navy Crosses. Cutter and crew sailed for Guam in August 1945, with orders to support the planned invasion of Japan. Three days later, the war was over, and the sub pivoted to non-combat missions. Daily life among Requin’s crewmen included “hot bunking”—taking a shift in one of about 30 shared berths—and 24/7 meals in the sub’s mess, which visitors can see in person or through a virtual tour.

Winslow Homer, The Wreck, 1896, Carnegie Museum of Art

The Wreck by Winslow Homer

Andrew Carnegie was a man not to be outdone. A year after the first Venice Biennale opened in Italy, his new museum-library hub in Pittsburgh hosted the first Carnegie International, then called the Annual Exhibition. Among the artists who exhibited in the 1896 International was 60-year-old American artist Winslow Homer. His oil painting, The Wreck, so impressed the judges that they awarded him the Chronological Medal and $5,000 in prize money. Soon after, the museum acquired it—marking one of the first paintings to enter the museum’s collection and one of more than 300 works acquired from 57 Carnegie Internationals. Homer is said to have based the work on a sketch he made of a disaster he witnessed from the dunes of Higgins Beach at Prouts Neck, Maine. Instead of the wreck itself, the focus is on the rescue team struggling to drag a lifeboat across the beach’s sand hills.

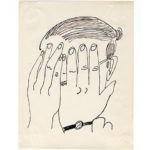

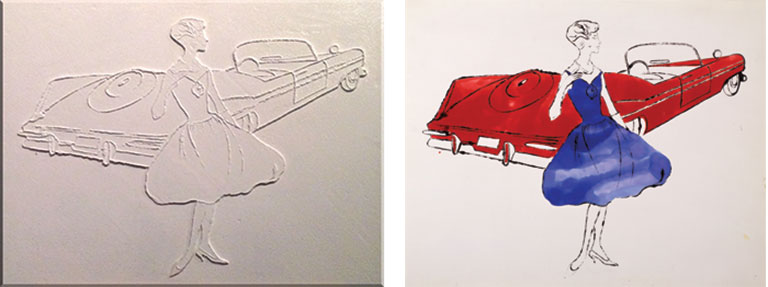

Andy Warhol, Female Fashion Figure, 1950s, The Andy Warhol Museum © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

Tactile Female Fashion Figure

Andy Warhol famously said, “Pop art is for everyone.” Following his lead, in 2014 The Warhol introduced the first of more than a dozen tactile reproductions of Andy Warhol artworks—think Campbell’s Soup I: Cream of Mushroom, Marilyn, and Female Fashion Figure. These three-dimensional representations give visitors a sense of the texture, shape, and composition of Warhol’s artwork through touch. The museum pairs each one with audio recordings by way of its Out Loud audio guide, which walks visitors through the experience of visualizing the original artworks by touching them. While they’re designed for visitors who are blind or have low vision, they give everyone a closer look—a closer feel—of what a Warhol artwork is all about.

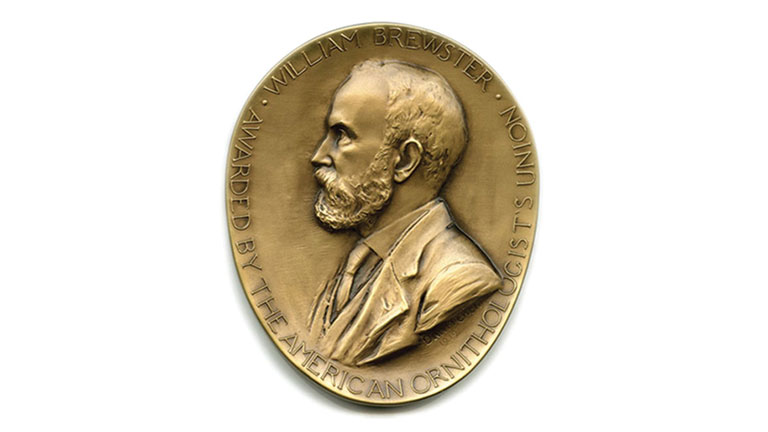

Brewster Medal (times two)

The Museum of Natural History began collecting birds before bird guides existed, at a time when identification took place through the barrel of a shotgun filled with “dust” to reduce damage to the specimens. In 1899, the museum hired W.E. Clyde Todd as an assistant in charge of all recent vertebrates, though he was shamelessly devoted to birds. He built that collection from the ground up, accessioning 136,295 specimens —a remarkable 66% of today’s holdings. Todd described 397 holotypes, or birds new to the world. He produced two major works, Birds of Western Pennsylvania (1940) and Birds of the Labrador Peninsula and Adjacent Areas (1963), the latter of which focused on an area of eastern Canada and earned him the distinction of being the only ornithologist to date to win a pair of Brewster Medals, in recognition of an exceptional body of work on birds of the Western Hemisphere. The prestigious honor from the American Ornithological Society dates to 1921 and was bestowed on Todd for the first time in 1925 for his co-work on the birds of Santa Marta, Colombia.

The Science Fair Project

Does insulating beehives aid overwintering honeybees? What are the effects of rapamycin and metformin on exosome secretion in cancer cells? Does screen time affect sleep? A regional institution since 1939, today’s Pittsburgh Regional Science & Engineering Fair is not your grandfather’s science fair. It’s a place where science is cool, optimism runs high, and scores of young scientists want nothing more than to change their world. Nearly 1,000 students in grades six through 12 compete from western Pennsylvania and northern Maryland. Hundreds of regional professionals weigh in as judges for the event that, all told, awards hundreds of prizes and scholarships. It’s a win-win for aspiring changemakers and our region.

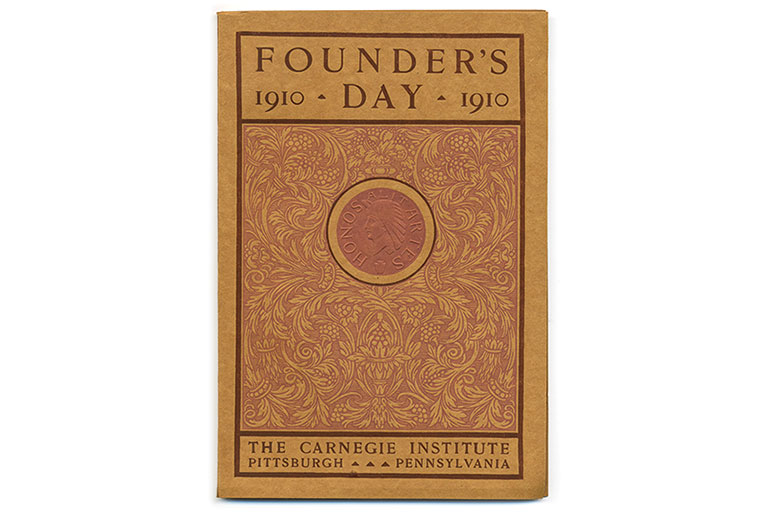

Founder’s Day Program

The Founder’s Day celebrations of the early Carnegie Institute were no small affairs. The 14th annual event should have occurred on April 29, 1910, but was postponed to May 2 to oblige the schedule of the celebration’s keynote speaker, President William Howard Taft. Every seat of Carnegie Music Hall was filled and the streets outside the building were packed with thousands of people gathered to catch a glance of the president and other dignitaries. In his remarks, Taft hailed the grand building, expanded three years earlier, as a “great temple of art, of music, and of learning.”

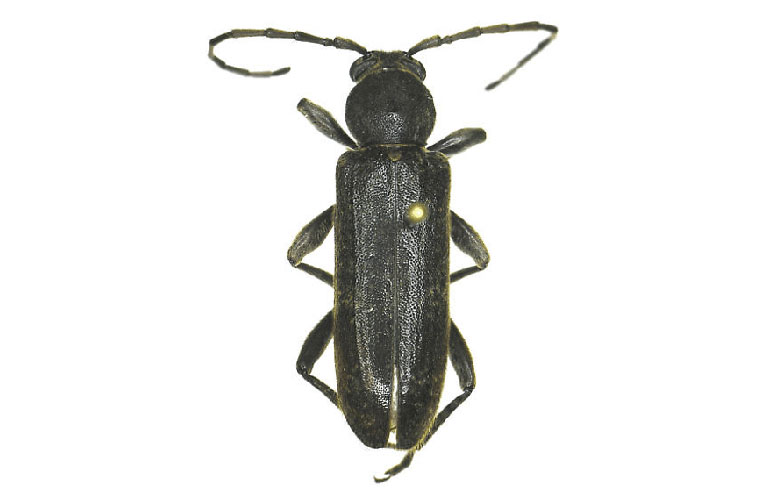

Karanasa pamira ornata

Andrey Avinoff’s Butterflies

Legend has it that Andrey Avinoff fell in love at first sight—with butterflies—at age 5, while roaming the grounds of his family’s expansive estate in Ukraine. At 7 years old, he discovered a future mentor in William J. Holland, an early director of Carnegie Museum of Natural History, when he immersed himself in Holland’s The Butterfly Book. By adulthood, Avinoff—also an accomplished artist—had become laser-focused on the study of the geographical variation in moths and butterflies across Asia, amassing a huge collection of specimens that would eventually be appropriated by the Zoological Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences. After fleeing his homeland during the Russian Revolution, Avinoff was recruited by Holland to bring his passion for butterflies to Pittsburgh, where he was able to more than replace his lost collection. Avinoff served as the museum’s director from 1926 to 1945, and the beauty and diversity of his collection is treasured to this day.

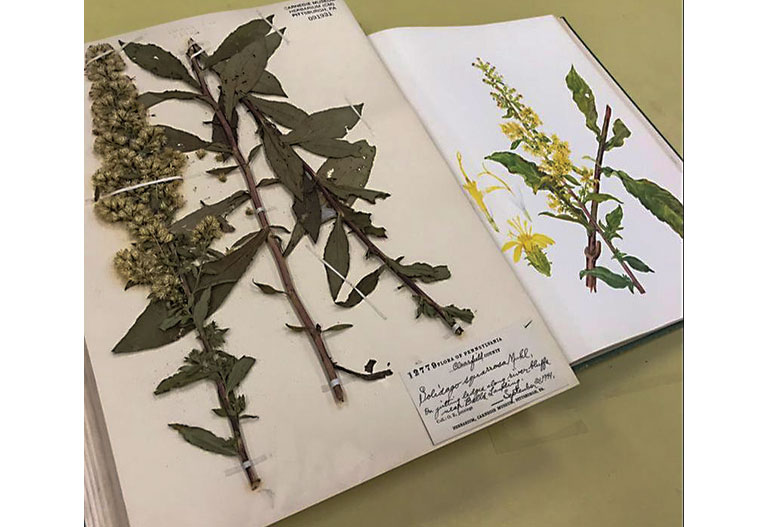

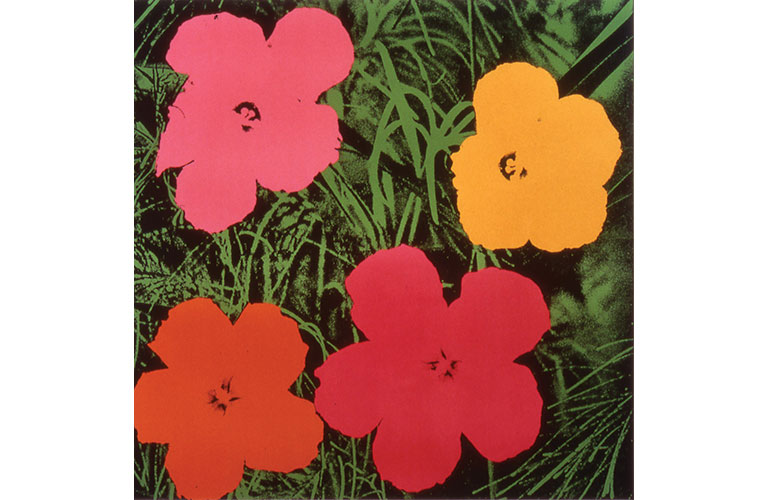

Wild flowers of Western Pennsylvania and the Upper Ohio Basin

Carnegie Museum of Natural History has been—and still is!—home to many accomplished scientists, and two stand out for their combined work on an amazing research and artistic feat: Wild Flowers of Western Pennsylvania and the Upper Ohio Basin, printed in 1953. It was 12 years earlier that Museum Director Andrey Avinoff, a renowned entomologist and an accomplished painter, began an ambitious project with friend and Curator of Botany Otto E. Jennings, who would succeed Avinoff as museum director. They wanted to describe and illustrate the flora of western Pennsylvania, based on Jennings’ lifelong study of the region. So, Jennings and his colleagues would bring living plants into the museum, and Avinoff worked quickly to paint each specimen, many of which were then dried, pressed, and placed in the museum’s herbarium. Jennings collected this squarrose goldenrod (Solidago squarrosa) on Sept. 21, 1944, on a ledge along the river bluffs near Bells Landing, Pennsylvania. Volume I of the duo’s historic publication is focused on descriptive content, including maps, the botany of the region, and descriptive text of the flora. In volume II, Avinoff’s 200 color drawings take center stage. It’s a singular accomplishment still greatly admired nearly 70 years later.

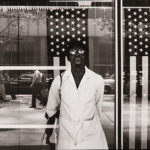

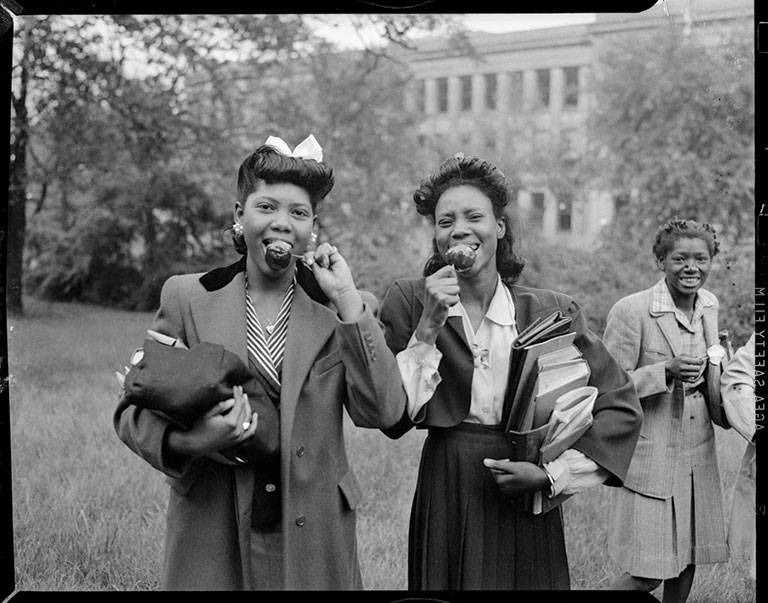

Charles “Teenie” Harris, Young women eating caramel apples, including Helen Ruth Daniels in center, possibly Schenley High School, ca. 1940–1946, Carnegie Museum of Art; Heinz Family Fund

Teenie’s Archive

As a newspaper man, Charles “Teenie” Harris lovingly captured his community’s everyday—its vibrant cultural, economic, and political life—through more than 70,000 photographs, earning him the distinction of being one of the most prolific photographers of the 20th century. Harris took most of his images in Pittsburgh’s Hill District and surrounding communities while on assignment for the country’s widest-selling Black newspaper, the Pittsburgh Courier, and they tell more than a local story. Acquired by Carnegie Museum of Art in 2001, the Teenie Harris Archive is considered one of the country’s most detailed and intimate photographic records of the Black urban experience.

Pseudomorph of Hemimorphite After Calcite

On certain days, it’s easy to figure out which are the stars of Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s Hillman Hall of Minerals and Gems: at closing time, just check out the number of fingerprints on the specimens’ glass cases. Without question, the megastar of the group—for well over a century—is the yellowish-gold pseudomorph of hemimorphite after calcite, unearthed from the ore fields near Joplin, Missouri, and gifted to the museum by A.L. Means in 1897. With only a handful in existence, it remains the signature piece of the collection, and can be found encased behind plexiglass—nearly glowing—in the hall’s Masterpiece Gallery.

Nicole Eisenman, Prince of Swords, 2013, Carnegie Museum of Art;

The Henry L. Hillman Fund

Prince of Swords by Nicole Eisenman

Known primarily for her painting, Nicole Eisenman came to prominence in the 1990s with her darkly funny, almost cartoonish canvases that satirize everything from politics to the nuclear family, art, and gender stereotypes, sometimes all in a single work. During the 2013 Carnegie International, she was awarded the prestigious Carnegie Prize for her career-spanning survey of painting paired with new sculpture in the museum’s Hall of Sculpture, where one of her figures remains today, playing with its distant cousins, the Greek and Roman casts. Prince of Swords sits with its feet dangling over the balcony, hunched over a smartphone. With a crystal lodged in its throat chakra, the figure personifies communication: “How we are drawn together, and also not, through ways we communicate,” says Eisenman. “I don’t really feel like it’s possible to be alone in this world. But here’s the way we have of being alone in the crowd.”

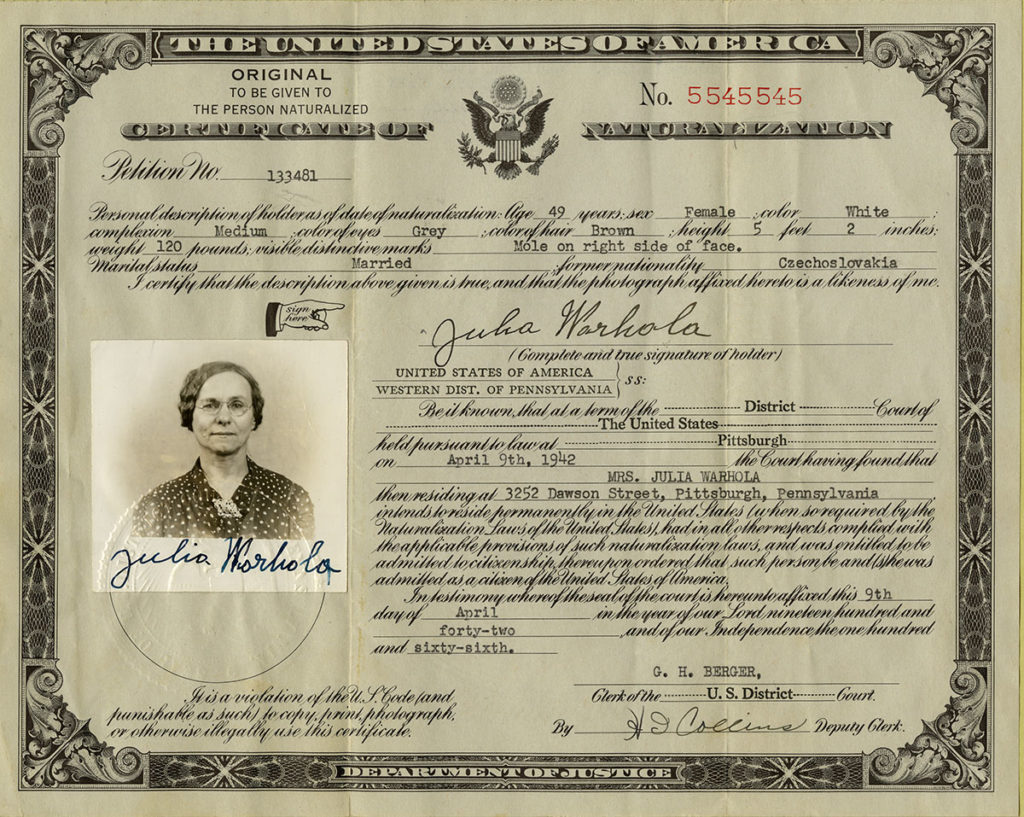

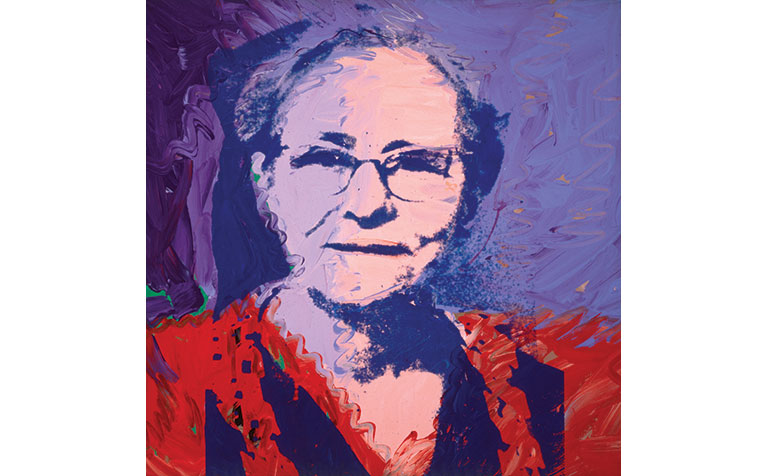

Julia Warhola’s Naturalization Certificate

When Julia Warhola, mother of Andy Warhol, received her naturalization document at the age of 49, she never could have imagined it would one day be exhibited in a museum. Now displayed on The Andy Warhol Museum’s top floor, it’s an artifact of, hands-down, the most important person in the Pop artist’s life. She was born Julia Zavacky in Mikova, Czechoslovakia, on November 17, 1892. Hers was hardly an exceptional immigrant story, except she loved to draw and she passed that love of drawing on to her children, including her youngest, Andy. After Andy moved away from Pittsburgh, he and his mother would live together in New York from 1952 until a year before her death in 1972. Her decorative handwriting, which Andy admired, often found its way into his illustrations, as did her drawings of her favorite subjects—angels and cats.

Industrial Fan

In 2005, while welcoming guests to Works Theater at Carnegie Science Center, educator Mike Hennessy met a young visitor with autism who was captivated by an old pedestal fan in a staff hallway, barely visible near the theater entrance. As it turned out, during the boy’s subsequent trips to the museum, he grew enamored with the fan, even giving short tours of it to other children. After visits, he would spend hours drawing it. Hennessy learned this one day when he discovered the boy and his family searching for the fan. Staff, it seems, had unwittingly moved it. So, the Science Center team sprang into action, searching the building until they located the fan, returning it to its place of honor. The child and his family continued to visit the Science Center—and the fan—for several years, until one day staff surprised the now-teenager with the fan as a Christmas gift, cleaned and dressed in a bow. Not long after, the young man’s mother sent a collage of photos showing the boy growing up at the Science Center—visiting the fan, searching for it, and finally observing it proudly as a permanent exhibit in his home. “It speaks to how we don’t know what will inspire our guests, and we don’t always know—in the moment—the kind of impact we’re having,” notes Steve Kovac, the Science Center’s senior director of service and engagement.

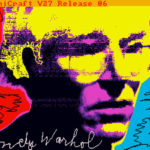

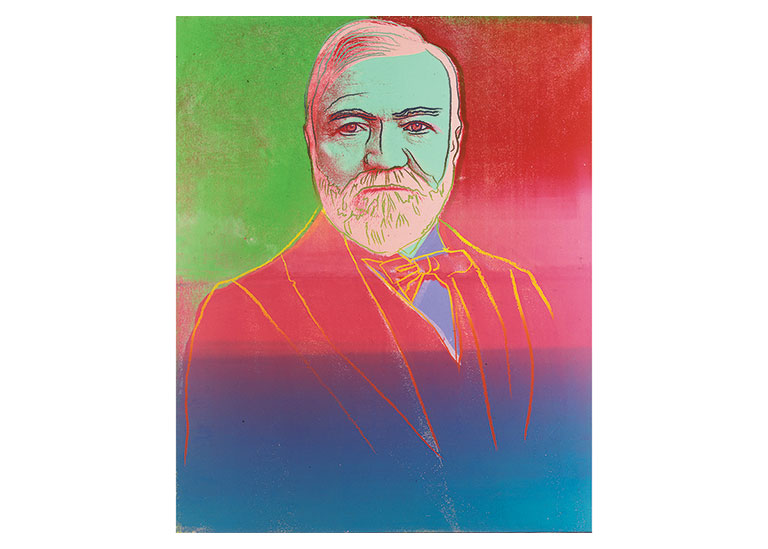

Andy Warhol, Andrew Carnegie, 1981, Gift of The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

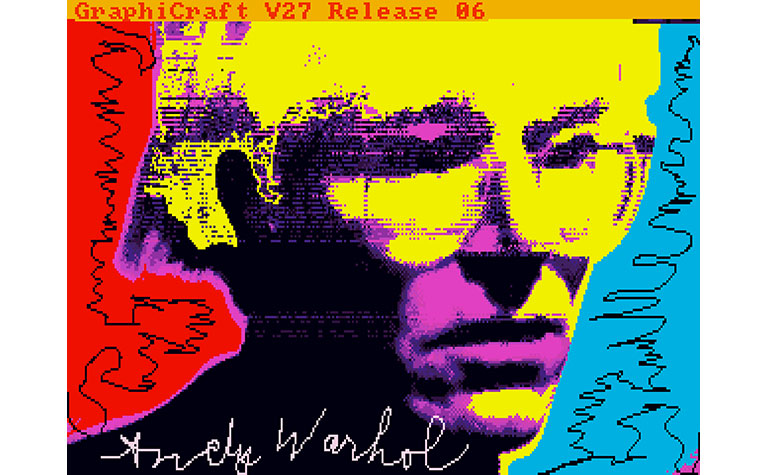

Andrew, by Andy

With Richard Mellon Scaife’s support, in 1981 Carnegie Museum of Art commissioned Pittsburgh’s most famous artist to create a portrait of Carnegie Museums’ founder. It’s only fitting that it be Andy Warhol, who attended Saturday art classes at Carnegie Museum of Art and studied painting and design at what’s now Carnegie Mellon University—both institutions established by Andrew Carnegie. The artist based his silkscreen of the complex figure on a photograph taken in 1896 by celebrated Pittsburgh photographer B.L.H. Dabbs. Warhol created two versions and both are in the museum’s collection. This one was a gift of The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts following Warhol’s death. Screened in vibrant complementary colors, the works give the buttoned-down look of the steel magnate something akin to an electric charge.

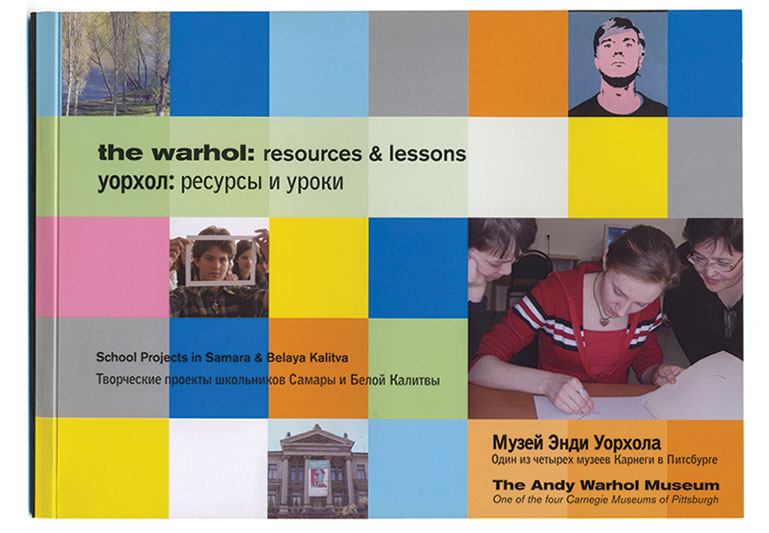

Warhol: Resources & Lessons English-Russian Workbook

Over 25 years, the keepers of the Andy Warhol flame have brought his art to more than 40 countries, reaching some 12 million people. In a particularly remarkable exchange, in 2005 The Warhol traveled the exhibition Andy Warhol: Artist of Modern Life to three major Russian cities. With support from the Alcoa Foundation, the museum established an educational partnership with the host institutions in Russia, which included the translation of educational resources, like this workbook, and a collaboration between students in Moscow and Pittsburgh. The project galvanized nearly a decade’s worth of work by The Warhol’s education department to create a free, and still evolving, online curriculum using Warhol’s life, art, and practice to teach lessons across the humanities.

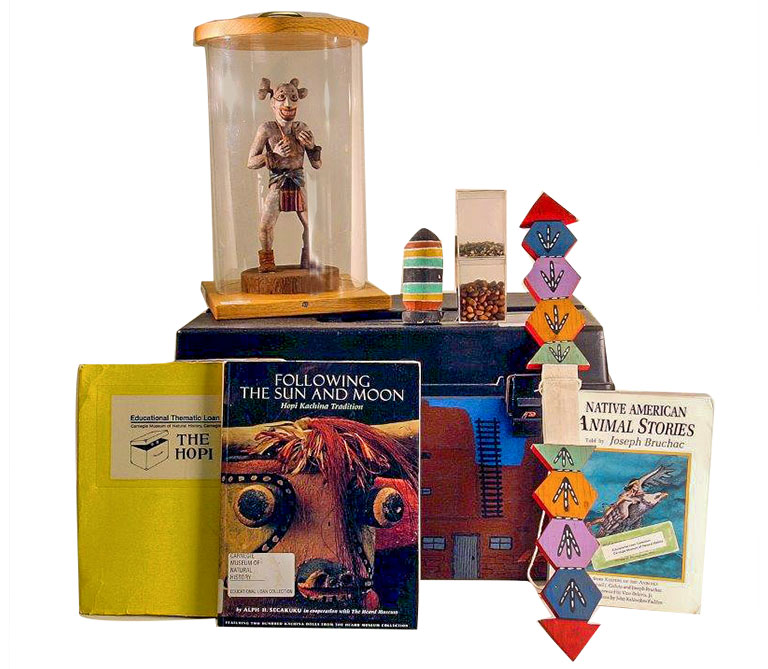

An Educational Kit: The Hopi Tribe

For nearly 125 years, the Museum of Natural History’s Educator Loan Collection, the brainchild of early Museum Director William J. Holland, has introduced area teachers and students to real, touchable artifacts and specimens of the natural world—from minerals and skulls to feathers, furs, and taxidermy. Themed by topic into tool kits—think dinosaurs, minerals, and Pennsylvania botany— additions to the now 8,000-plus collection are often donated by the museum’s scientific sections because they’re lacking sufficient data for scientific study. They’re no less valuable, though, as educational tools for K–12 learners. Included in this kit about the cultural heritage of the Hopi, a Native American tribe who primarily live in northeastern Arizona, is a letter from a Hopi carver. “I began carving when I was about 8 years old. I learned by sitting and watching my uncles and fathers carve beautiful figures of Katsinas,” writes Patrick Joshevama, who considers his carved works to be “my footprints upon this Earth.”

A Patch of Pittsburgh Past

On November 5, 1895, when Andrew Carnegie dedicated his “palace of culture,” the grand building was a glistening reminder of the value the steel baron placed on learning. Decades later, that same building, now blackened by layers of industrial soot, was an ominous reminder of the once unchecked environmental consequences of burning fossil fuels to power Carnegie’s steel mills and other industrial polluters. In the fall of 1989, library and museum leaders took on the task of cleaning the building’s Berea sandstone exterior—all but a small corner left black as a reminder of what once was. The public was invited to sponsor patches of the building, and the $1.3 million face-lift finally began after years of study to determine the safest way to clean the façade of the 104-year-old historic landmark. By the end of 1990, the building was returned to its onetime glory.

The School Bus

On most spring days and just before the annual holiday break, the school bus is an ever-present part of the Carnegie Museums landscape. But, unfortunately, not as often in the age of COVID-19. The first time most young visitors meet Dippy, strike a pose mid-stride with the Walking Man sculpture at the Museum of Art, get lost in the Science Center’s Miniature Railroad & Village®, and learn to silkscreen at The Warhol is usually on a school field trip, arriving on a yellow school bus. Each year, some 100,000 schoolchildren find unique sources of inspiration, knowledge, and fun at the museums.

Photo: Tom Little

The Façade of Saint Gilles

At 38 feet high and 74 feet long, the plaster cast of the west portal of Saint-Gilles-du-Gard, a Benedictine abbey in the south of France, still impresses today, 114 years after visitors first set eyes on it. Considered by many to be the most beautiful of all the great Romanesque portals, it only made sense that Andrew Carnegie wanted it to be the star of his collection of custom-built architectural casts. His Carnegie Museum paid the town of Gard 2,000 gold francs—about $80,000 in current U.S. dollars—for permission to make the huge cast from the original 12th-century church, a risky practice that soon would fall out of favor throughout Europe. It took three separate transatlantic voyages to transport the 195 packing cases filled with carefully crafted piece molds to New York. Two French craftsmen would spend 18 months assembling the pieces of Saint Gilles in Carnegie Museum’s newly built Hall of Architecture.

Photo: Lisa Kyle

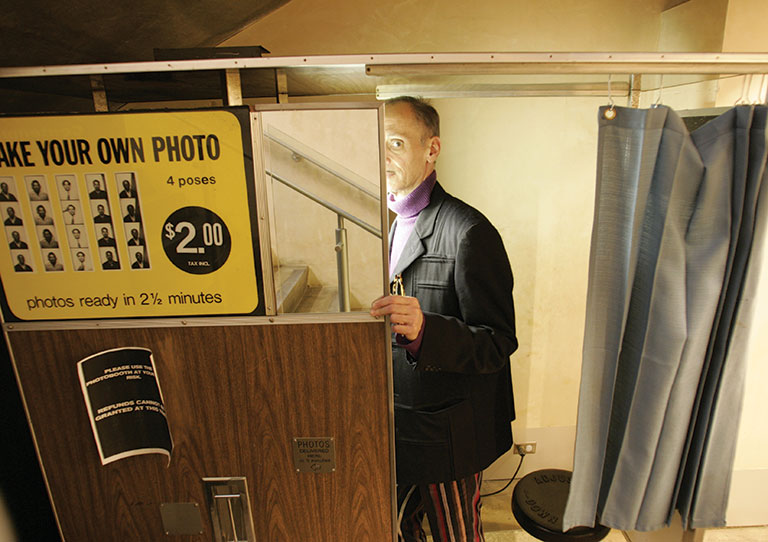

The Warhol’s Vintage Photo Booth

Andy Warhol liked the simple and quick technology of the four-for-a-quarter photo booth, and he used the photo strips to create silkscreen portraits, including of himself. The artist would encourage sitters such as art collector Ethel Skull to act out different looks and expressions, each captured in a single frame. It’s fitting, then, that on the underground level of The Andy Warhol Museum, Pop art fans can memorialize their visits inside a vintage photo booth that has been part of the museum since it opened in 1994—the four photo strips now $3. Famous visitors get in on the action, too, including John Waters, the self-proclaimed “filth elder” and Pope of Trash, seen here inside the booth in 2005. When this vintage machine is unavailable—and it happens—a modern photo booth, which allows visitors to share photos and a video of their session on Twitter and Facebook, is ready for takers on the first floor.

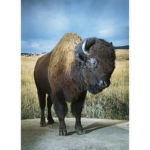

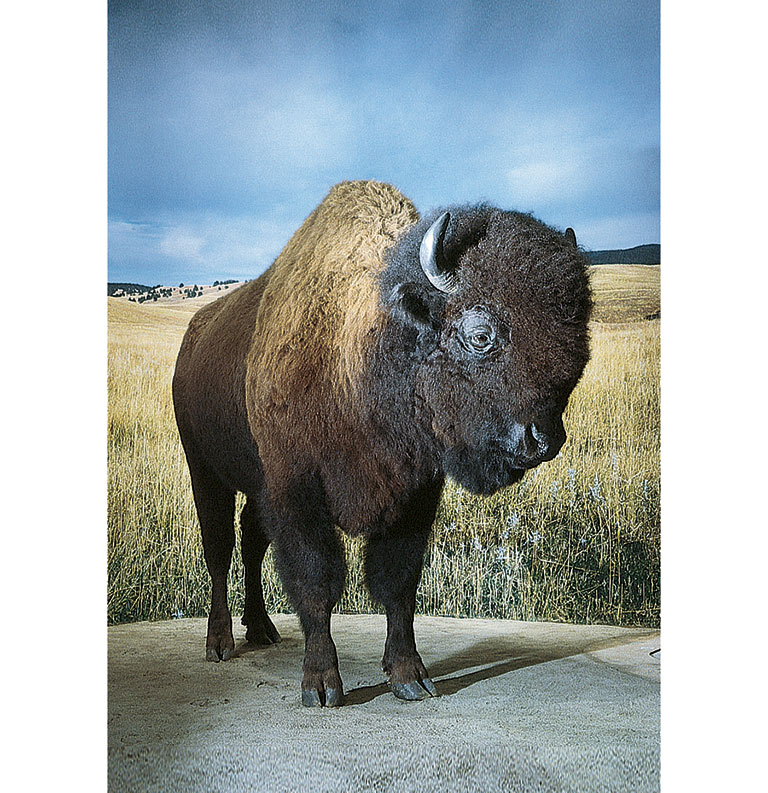

American Bison

For countless numbers of schoolchildren, the taxidermy bison standing tall in Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s Alcoa Foundation Hall of American Indians is a tour highlight because it’s real and touchable. It’s an intentional museum moment, centering the animal that is not just revered but also intertwined with the culture and spiritual lives of American Indians of the northern Plains. When planning for the hall in the early 1990s, museum staff identified the aging bison on a meat farm in nearby Mercer County. While staff knew that the bison is sacred to Native people, they didn’t understand how the relationship worked. They soon learned from Indigenous advisers that they must ask the bison if it was willing to be used for this purpose. According to Lakota legend, the bison made a pact long ago to feed the people. In return, special ceremonies are performed when bison are killed. The museum asked Rosalie Little Thunder, a Lakota spiritual leader and one of several Indigenous advisers to the museum, to perform the ceremony. With museum staff in attendance, Rosalie announced that the bison had agreed to be used for educational purposes.

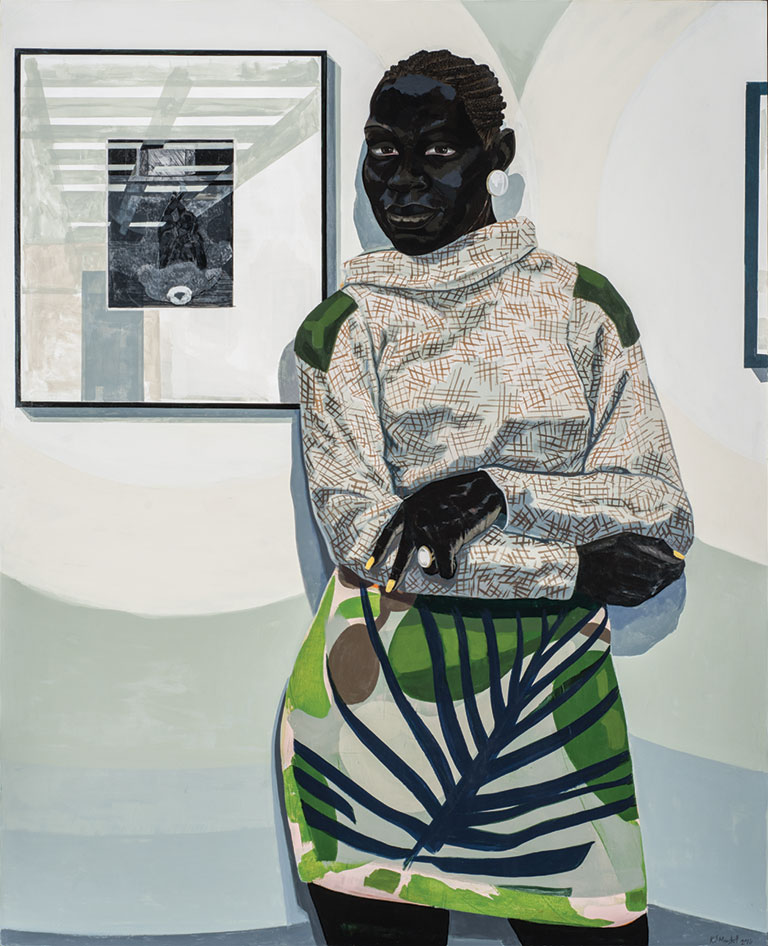

Kerry James Marshall, Untitled (Gallery), 2016, The Henry L. Hillman Fund © Kerry James Marshall. Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner, London

Untitled (Gallery) by Kerry James Marshall

Considered one of the greatest living painters in America, Kerry James Marshall is best known for reinserting Black figures into the largely white historical canon of Western painting. For Eric Crosby, the Henry J. Heinz II Director of Carnegie Museum of Art, he was the artist who got away. Although Marshall exhibited a far-out comic strip populated by a cast of Black heroes in the 1999 Carnegie International, the museum had failed to acquire his work. When Crosby joined the museum as a curator in 2015, he was determined to right that wrong, and in December 2016 the museum did just that by purchasing a new painting by Marshall. In Untitled (Gallery), the juxtaposition of the primary figure and the nearby photograph on the wall prompts a host of questions, Crosby writes: “Is the subject of the painting also the subject of the photograph? Is she the artist? The curator? Or perhaps the gallerist? Is she the owner of the artwork or just an interested viewer? If Marshall’s goal has been to bring the Black figure emphatically into the field of art, and indeed into the museum, then Untitled (Gallery) takes this aim directly as its primary subject matter.”

Oakland Muses

Thanks to sculptor John Massey Rhind, the Forbes Avenue entrances to Carnegie Music Hall and Carnegie Museums in Oakland are hard to miss. That’s because they feature the larger-than-life bronze statues of Shakespeare, Michelangelo, Bach, and Galileo—the personification of the literature, art, music, and science found within. But often overlooked are the 12 muses who stand 12 feet tall and hover 80 feet above. Grasping the tools of their trades—among them a quill pen, a painter’s palette, a lyre, even a chemist’s flask and a fossil —these female spirits are said to provide encouragement for earthly pursuits. They were added during the first expansion of the grand building, completed in 1907.

Small snail fossils found in a Grand Staircase wall.

“Hidden” Fossils

Visitors who explore the shared Carnegie Museums and Library building in Oakland often marvel at the architecture and its head-turning multicolored marbles and limestones. What they might overlook, however, are the fossils buried in those beautiful stones. Look closely at the columns and pillars of the Grand Staircase and the walls in the Music Hall foyer and you’ll find a variety of seashell species preserved in the Échaillon limestone, mined from cliffs in the valley of the Isère River of the western Alps in southeastern France. Look closely at the beige Hauteville stone, also from France, that covers the Grand Staircase walls and the floors of the Halls of Sculpture and Architecture to discover 5-inch-long Nerinea snails. It took Albert Kollar, geologist and collection manager for invertebrate paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History, and his French colleagues years of fieldwork to authenticate the provenance of the stones.

Soot-Covered Eastern Towhees

Long before people monitored air quality through electronic devices, the soot on birds’ bellies recorded the history of air pollution. From 1880 to 2015, the soot stains on the plumage of birds preserved in museum collections in Chicago, Detroit, and Pittsburgh clearly decline in line with legislative and social changes of the 20th century, such as the switch from coal to natural gas in residential heating. Black carbon, in addition to being a public health hazard, is a major contributor to anthropogenic climate change. Thanks to the research of a pair of University of Chicago graduate students who measured the black carbon on some 1,300 birds from the collections of the Field Museum, the University of Michigan Museum of Zoology, and Carnegie Museum of Natural History, a clear picture of emissions in the past emerged, which will help to improve the accuracy of future climate scenarios. Carl Fuldner and Shane DuBay published their findings in 2017 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Because birds molt their feathers annually, the soot on the bird at the time of its death—including on these eastern towhees once on view in Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s Anthropocene Living Room—is a snapshot of that year in industrial history.

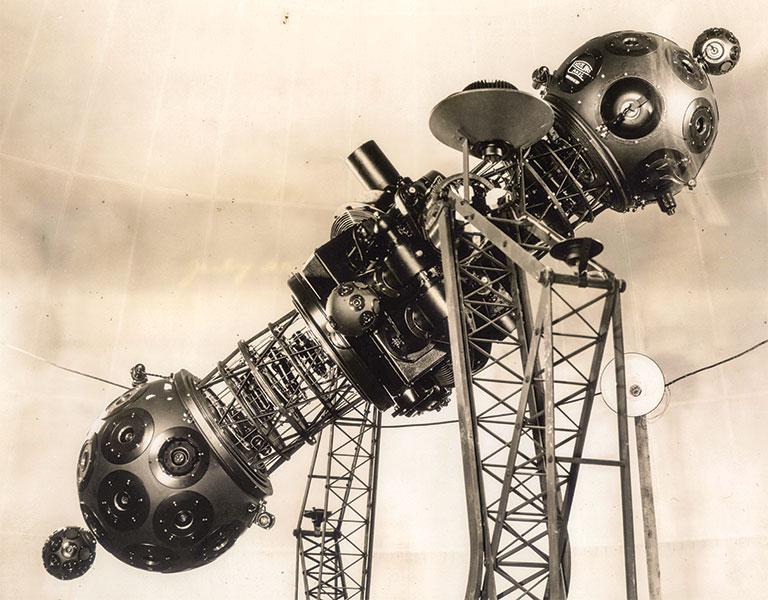

Zeiss Star Projector

The Zeiss Model II Star Projector sure could make an entrance. For more than 50 years, every show at the original Buhl Planetarium would begin with the alien-looking contraption dramatically rising from the floor. And then, as if by magic, it would illuminate the domed ceiling with the sight of more than 9,000 stars. It was the ingenuity of Carl Zeiss and the optical manufacturing company that bears his name that made it all possible. Complex clockwork mechanisms allowed the projector to accurately display the stars as they would appear at any point in time, from any place on Earth. But with the opening of Carnegie Science Center in 1991 and the ever-growing use of digital technology, its magic began to fade. Although long retired from duty, the Zeiss still looms large on the first floor of the Science Center where it stands as the focal point of a permanent interactive exhibit.

The Crowning Of Labor

John White Alexander had his marching orders: Paint an homage to the hardworking people and industrial achievements of Pittsburgh. He delivered a three-story, 4,000-square-foot mural that still surrounds Carnegie Museums’ Grand Staircase. When Andrew Carnegie welcomed crowds to his newly expanded Pittsburgh museums in 1907, the spectacle of Alexander’s The Crowning of Labor greeted them at the building’s majestic new entrance. The drama of Alexander’s mural starts on the first floor, with muscled male laborers toiling away in the steam and smoke of their industrial workplace. On the second floor, three panels tout the glory of labor, symbolized by an ascending male figure clad in a suit of armor (Carnegie, maybe?). On the third floor, Pittsburgh citizens march toward an enlightened, sunlit future, but the panels representing the fruits of their labor—art, music, literature, and science—remain blank; Alexander died before completing them. It’s hard to believe the entire mural was painted in New York City, shipped to Pittsburgh, and then glued onto the walls. In 1995, Museum of Art conservators cleaned and restored the mural in honor of Carnegie Museums’ centennial.

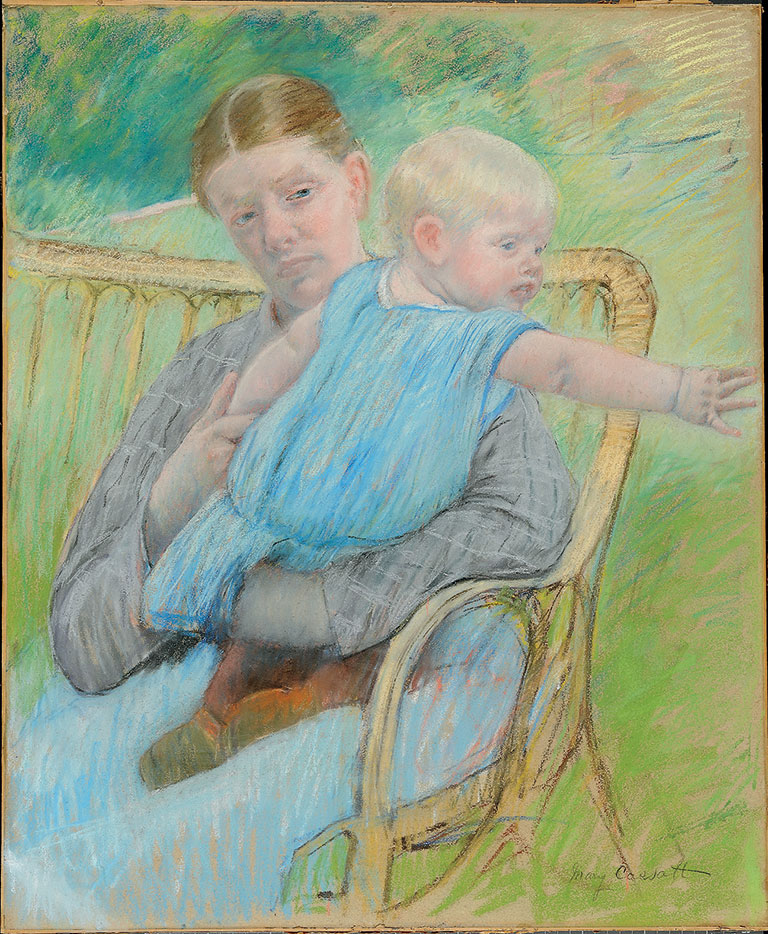

Mary Cassatt, Mathilde Holding Baby, Reaching out to Right, c. 1889, Carnegie Museum of Art, Heinz Family Fund, Robert S. Waters Charitable Trust Fund, Major Paintings Acquisition Fund, Alan G. and Jane A. Lehman Fund, Alice and Jim Beckwith Art Acquisition Fund, and Foster Charitable Trust Fund

Mathilde Holding Baby, Reaching out to Right by Mary Cassatt

In 2011, Carnegie Museum of Art added this major pastel by Mary Cassatt to its collection. Mathilde Holding Baby, Reaching out to Right represents not only a medium for which the native Pittsburgher is renowned, but it’s also an early, energetic example of the artist experimenting with what would become her signature subject: mother and child. The sitter is Mathilde Valet, the artist’s housekeeper and companion for many decades. While her hands are intertwined, Mathilde’s expression is ambiguous, and the baby appears to be reaching for something just beyond the frame—a compositional strategy the artist used across a range of subjects, in a sense teasing the viewer. Cassatt was one of three women and the only American to show with the French Impressionists. The museum collects her work in depth, with a painting and 19 prints also part of its collection. Impressionists. The museum collects her work in depth, with a painting and 19 prints also part of its collection.

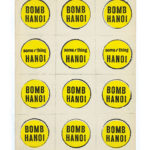

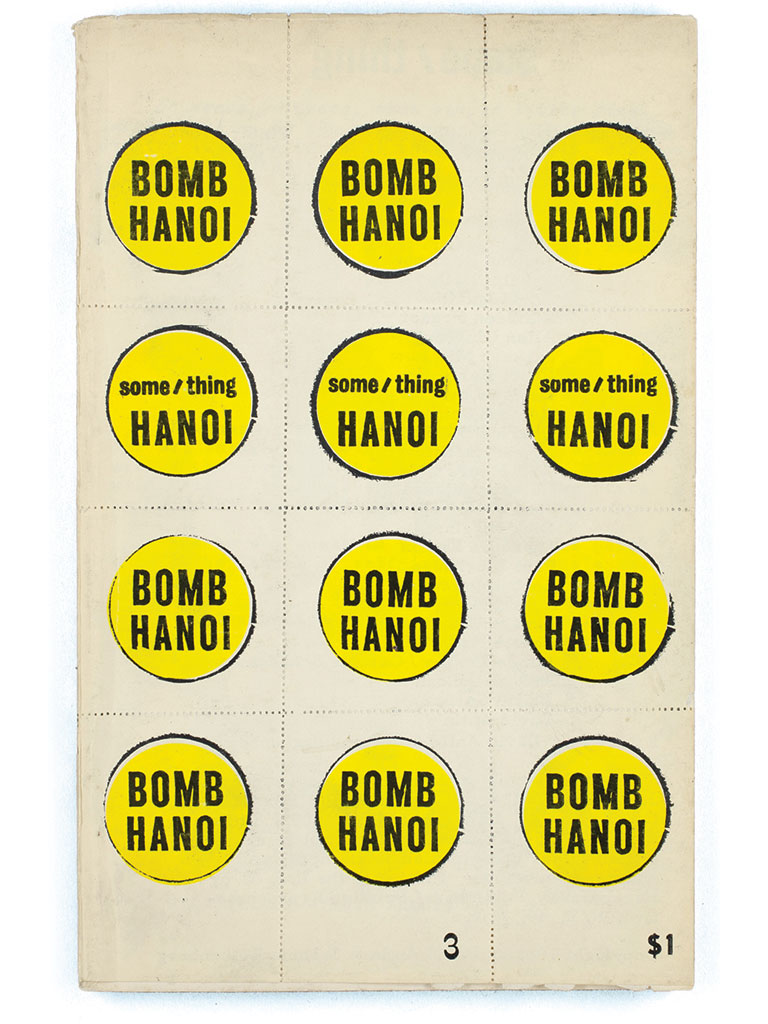

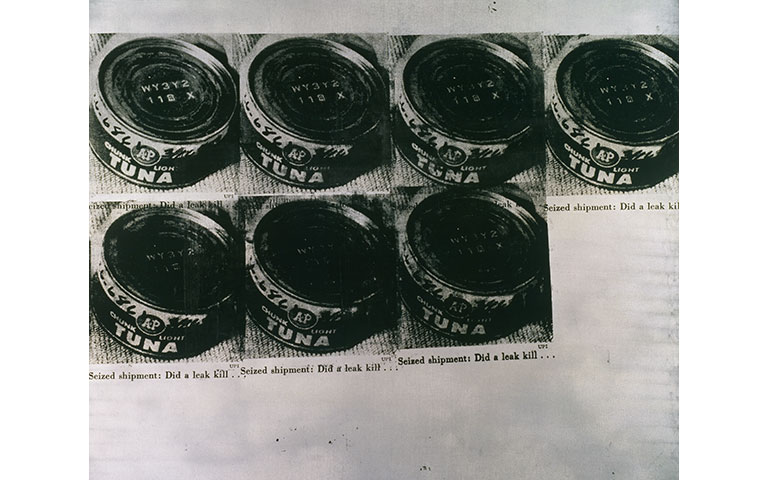

Andy Warhol (cover design), Some/thing – Vol. 2, no. 1 (Winter 1966), 1966, The Andy Warhol Museum; Gift of Jay Reeg

Cover of some/thing by Andy Warhol

Andy Warhol was famously ambiguous when asked about the meaning or intent of his artwork. But if you pay attention, says Matt Gray, manager of The Warhol’s archives, you can piece together many of the artist’s social and political beliefs. When David Antin, the editor of underground poetry magazine some/thing, approached Warhol about designing the publication’s winter 1966 cover, an issue all about the Vietnam War, Antin suggested that the artist use a popular pro-war slogan—with a twist. The idea was to get war supporters to pick up the magazine and read it, Antin wrote in Design Observer, only to be greeted by anti-war poetry by the likes of Allen Ginsberg. Warhol, who originally pitched a Vietcong flag for the cover, didn’t disappoint. He created perforated sheets of real glue-backed stamps for the front and back covers that scream “Bomb Hanoi” and could be conveniently torn out and pasted on telephone poles or subway walls.

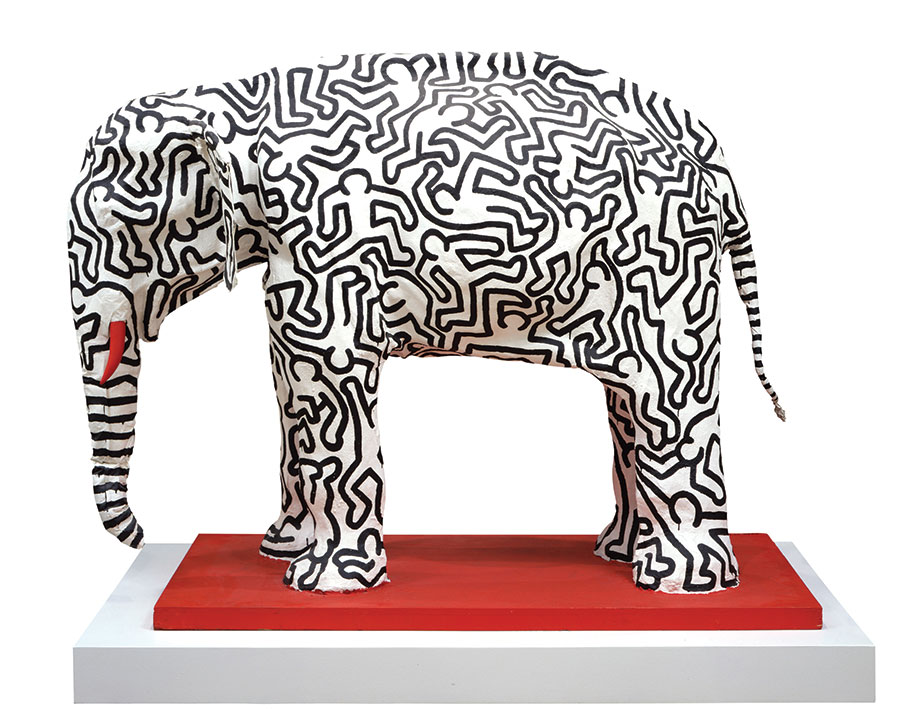

Champion Ador Tipp Topp (“Cecil”) 1921-1930, 1931, The Andy Warhol Museum; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

Cecil

Cecil, the “guard dog” for Andy Warhol’s Factory, appeared in photos with the artist’s Superstars and in his series of dog paintings. Procured from an antiques shop around 1970, the stuffed Great Dane was said to have belonged to legendary film director Cecil B. DeMille, hence his name. But as a canine photographer and genealogist discovered two decades later, Cecil’s pedigree was far more impressive. His true name was Ador Tipp Topp, and he worked the dog show circuit, taking home the 1924 Westminster Kennel Club Best of Breed crown. The showstopper died in 1930, and his taxidermied remains were gifted to the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History, where the specimen obediently stayed until the mid-’40s. His afterlife journey eventually took him to the antiques store, where he acquired the famous name and famous owner. When Warhol died, Cecil found his eternal resting place at The Andy Warhol Museum.

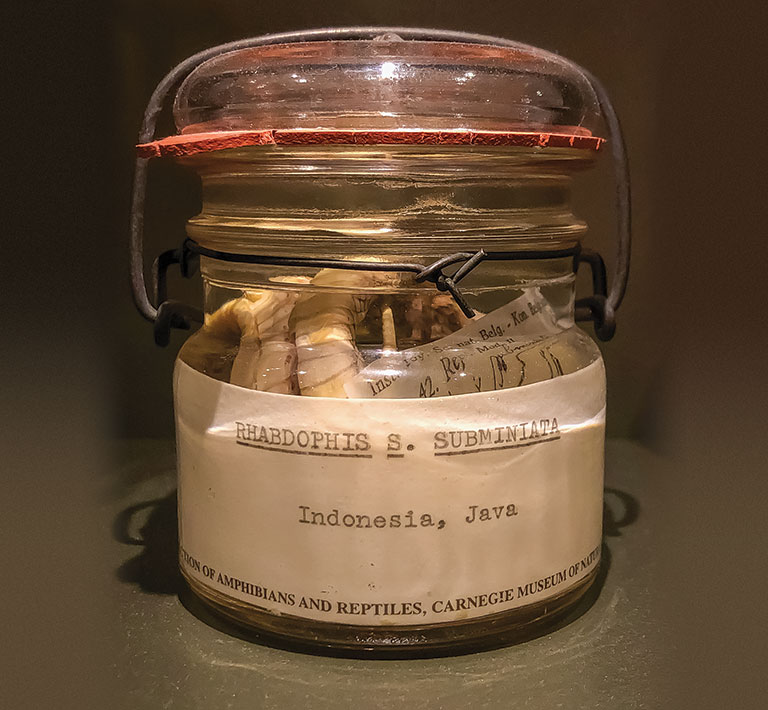

Red-Necked Keelback, Collected In 1872

In its wonderfully creepy Alcohol House, Carnegie Museum of Natural History boasts about 230,000 reptiles and amphibians from 160 countries—95% of them fluid-preserved in jars. Each is a scientific time capsule, which is why researchers across the globe use them to study the ecology and evolution of species and their environments. Jennifer Sheridan, curator of amphibians and reptiles at the museum, recalls sleuthing for specimens from Southeast Asia when she came across a common snake known as Rhabdophis subminiatus (or red-necked keelback), that hailed from an uncommon locality—Java, Indonesia. “The exact location detail is what caught my eye,” Sheridan notes; “the island of Ternate, where British naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace was when he wrote his famous letter to Charles Darwin in 1858, explaining to Darwin his idea of evolution by natural selection.” While traveling across Indonesia, Wallace had noticed a distinct change in the species of plants and animals found in two neighboring island groupings. Darwin would later jointly publish his own work on the topic alongside Wallace’s. While the date of the specimen, 1872, is 10 years shy of being linked to Wallace’s work on the island (he left a decade earlier), it’s among the oldest in the museum’s collection.

Freshwater Seal Holotype

In 1935, Carnegie Museum of Natural History Curator of Mammals J. Kenneth Doutt first saw evidence of an uncommon find while doing fieldwork in Quebec, Canada. He observed an Inuit man carrying a sealskin bag with fur he had never seen. There were local rumors of a freshwater seal, but it would take another three years and a well-planned winter expedition to find this mammal, previously unknown to science. Joined by Curator of Ornithology Arthur Twomey and Inuit guides, they trekked into the poorly mapped interior of Quebec to a chain of freshwater lakes where the elusive Ungava harbor seal, an uncommon freshwater relative of the better-known Atlantic harbor seal, was said to live. For the next eight months, they, too, called the Ungava Peninsula and Hudson Bay home. Upon their triumphant return to Pittsburgh, the pair brought with them the holotype, or the original specimen used to name the new subspecies of freshwater seal. In the 1980s, to help inform the new Wyckoff Hall of Arctic Life, museum staff retraced Doutt’s steps, and met Inuit people who remembered the 1938 fieldwork fondly.

E-Motion

Is it searching for signs of alien life in space? Not quite. Also known as the weather cone, Carnegie Science Center’s trademark E-Motion cone was designed by New York architect Shashi Caan and lighting designer Matthew Tanteri. Hard to miss at 66 feet wide and 44 feet tall, the illuminating sculpture was installed in 2000 atop The Rangos Giant Cinema as a weather beacon for Pittsburgh. Its computerized lighting system, controlled by the Science Center’s weather partner, WTAE-TV, displays different colored lights based on the weather forecast: red for warmer weather, blue for cooler, green for no change, and yellow for a rain or snow warning.

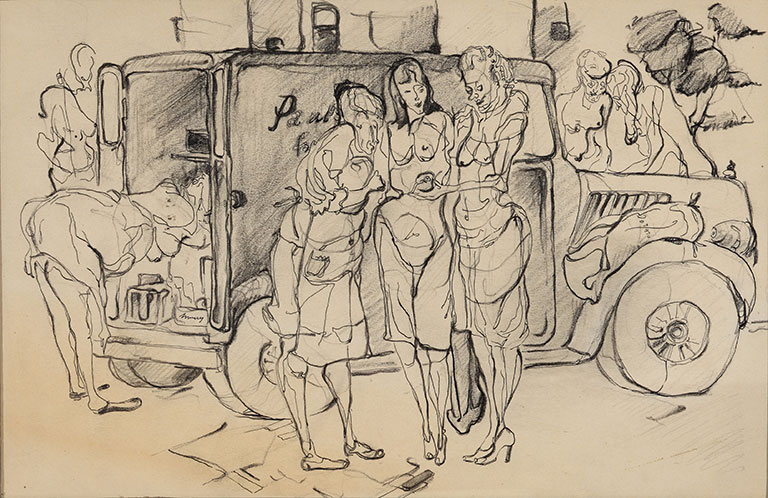

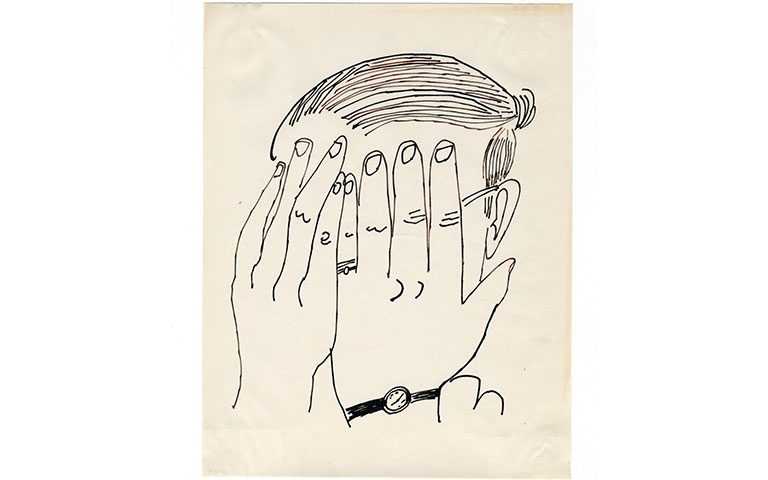

Andy Warhol, Women and Produce Truck, 1946, The Andy Warhol Museum; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

Women and Produce Truck by Andy Warhol

Before he became a household name, Andy Warhol almost flunked out of art school at Carnegie Institute of Technology, now Carnegie Mellon University. At the end of his freshman year in 1946, Warhol’s instructors put him on academic probation, calling his style too primitive. That summer, the artist honed his skills by following brother Paul, who sold produce from a truck. Traveling the streets of his childhood neighborhood of South Oakland, Warhol sketched the women who bought the fruits and vegetables. While the drawings were considered conformist by Warhol’s standards, they were in line with what was considered beautiful at the time. The early sketches helped Warhol establish himself as a star student. That fall, he won the Martin B. Leisser Prize and had the works exhibited in the college’s fine arts gallery.

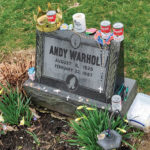

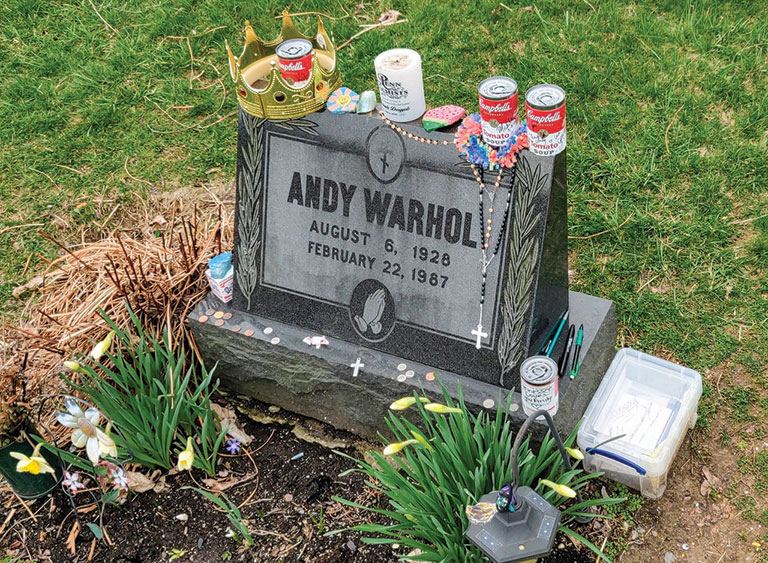

Andy Warhol’s Gravesite

To the surprise of many, Andy Warhol is buried near his parents, Julia and Andrej Warhola, in the small St. John the Baptist Byzantine Catholic Cemetery in the suburb of Bethel Park, just south of Pittsburgh. Long a mecca for fans carrying with them Campbell’s soup cans, rosaries, personal letters, birthday cakes, and more, in 2013 The Andy Warhol Museum teamed up with EarthCam to make the gravesite viewable 24/7. At one time, the website hosting the live webcam allowed viewers to order offerings, and takers were given a time of day to observe their delivery. It’s all very Warholian—watching the final resting place of a man who liked to watch. Warhol, after all, pioneered motion pictures of motionless subjects and foretold, for good or bad, reality TV. In 2020, artist Madelyn Roehrig published Andy, Can You Hear Us?, a quirky celebration of the famous artist’s vibrant afterlife as depicted by the inspired visitors to his gravesite since 2009.

Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood Home

You can’t find it on a map. But the Neighborhood of Make-Believe still exists—beyond our imagination, of course—within Carnegie Science Center’s Miniature Railroad & Village®. The creation of Pittsburgh’s own Fred Rogers, Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood first aired on WQED in 1966. Over the course of 30-plus years and 895 episodes, the landmark show was an educational haven for children and their parents. On March 19, 2005, the day before what would have been Rogers’ 77th birthday, a tiny replica of Mister Rogers’ house—made entirely out of beeswax—found a home in the popular Science Center exhibit. There, the red trolley perpetually passes by as Fred himself, clad in his signature red cardigan and blue sneakers and flanked by two children, sits on the front-porch swing.

Pirate Parrot The Science Experiment

On October 5, 2015, days before the Pittsburgh Pirates played their wild-card game against the Chicago Cubs, the Pirate Parrot flew into the stratosphere and back. Not the real team mascot; rather, a plush Pirate Parrot toy launched inside a weather balloon from PNC Park, all in the name of out-of-this-world science. Students strapped the stuffed bird to the balloon as part of a collaboration between Carnegie Science Center’s Science on the Road program and education-based company StratoStar, launching the bird to an altitude of 96,000 feet—about three times higher than most commercial airplanes fly. High-definition cameras caught every minute of the flight, as the plush parrot peaked 18 miles above Earth’s surface, the curvature of the planet visible. The helium-filled balloon carried sensors measuring temperature, altitude, speed, and spin rate before popping, and a parachute guided the parrot back to Earth, where a team recovered it from a tree in Cranberry Township, about 15 miles from the ballpark.

3D-Printed Prosthetic Hand

In 2016, Carnegie Science Center’s BNY Mellon Fab Lab partnered with e-NABLING the Future, a global community of more than 1,500 volunteers, to make 3D-printed prosthetic hands. After a few months of training in the Science Center’s popular maker space, about a dozen area high school students got the chance to craft the prosthetic hands, which look like they might belong to a superhero. The students then led a group of community volunteeers in assembling the fully functional limbs, which were sent free of charge to children throughout the world who are missing all or part of their hands due to injuries from violent conflicts or disease.

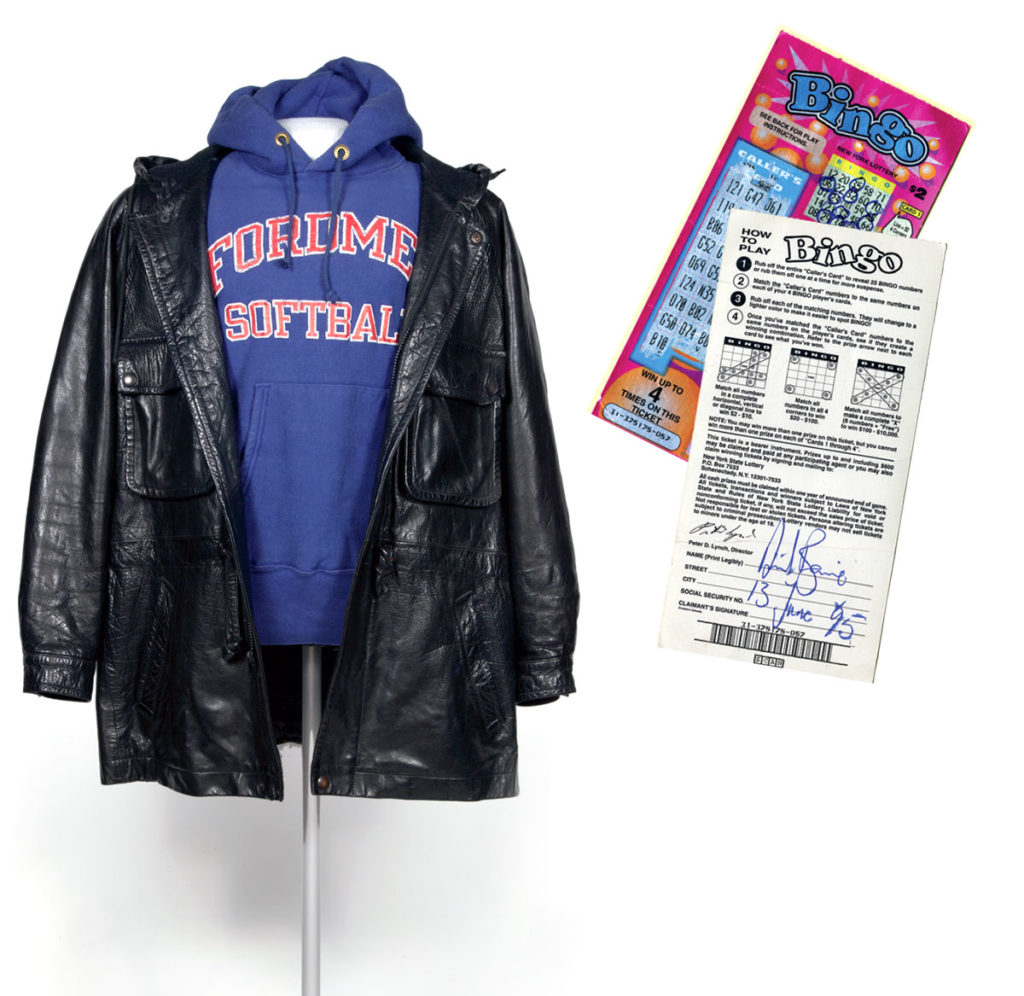

Calvin Klein, Calvin Klein hooded leather jacket, 1980s, The Andy Warhol Museum; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

Lottery ticket (Bingo, New York Lottery, June 13, 1995), 1995, The Andy Warhol Museum; Gift of David Bowie

Andy Warhol’s Leather Jacket With David Bowie Lottery Ticket

Tucked inside Box C25 (C stands for clothing) in The Andy Warhol Museum archives are the last personal items Andy Warhol touched. He wore or carried them with him to New York Hospital in Manhattan, where he died on February 22, 1987, two days after having his gallbladder removed. Among the items: documents from the hospital and this hooded Calvin Klein leather jacket, the receipt for the artist’s $2.40 taxicab ride to the hospital at 4:48 p.m. on February 19 folded inside its pocket. It’s the same jacket Warhol wore one month earlier to the opening of his final exhibition during his lifetime, Warhol—Il Cenacolo-, at Milan’s Palazzo delle Stelline (underneath it he sported a hoodie for the softball team of Ford Modeling Agency). The jacket would be worn by one other person after Warhol’s passing—David Bowie, when in 1996 the glam rock icon played Warhol in the film Basquiat. The museum agreed to lend one of Warhol’s wigs and the leather jacket to Bowie, a big fan of Warhol’s. When he returned the jacket, placed inside the pocket this time: a New York state bingo scratch-off ticket (a $5 winner), signed and dated by Bowie.

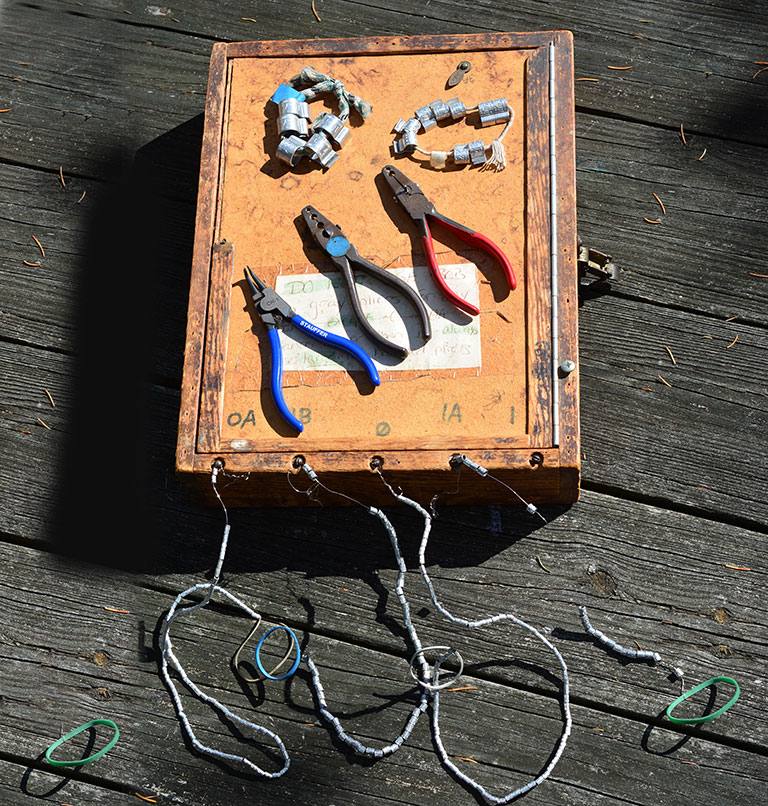

Bob Leberman’s Banding Kit

In 2021, Powdermill Nature Reserve’s world-renowned bird-banding program turned 60, having captured and released some 200 species of 800,000 individual birds! This original banding kit was used by late program founder Bob Leberman, a largely self-taught ornithologist who in 2004 retired after serving 43 years as senior bird bander. In the early years, Leberman had no physical lab, so Albert C. Lloyd, Leberman’s first banding assistant, designed and built this banding box as a convenient way for Leberman to carry supplies and later to organize the tiny silver bird bands at a stationary desk. He would attach the most-used band sizes to the screws on the outside of the box, and store larger, infrequently used sizes inside, along with the pliers he used to gently close the bands around birds’ legs. Finally, he would include the all-important data sheets used for recording a wealth of information about each capture—species, age, sex, wing length, fat deposits, and body mass. Today, the same process still takes under a minute, with the specs for each bird entered directly into a database.

Hoops

Kids and grown-ups alike stared in awe at Hoops. The 3-ton orange robotic basketball arm could do what no human could do—make nearly 94% of its free throws. In its center court spot at Carnegie Science Center, Hoops was a phenom, effortlessly making behind-the-back, 22-foot throws. Built in 1995 as a welding arm for the automotive industry, it debuted at the Science Center the following year as the world’s first professional-grade basketball-shooting robot. After making road trips as a loaner to other museums, Hoops returned home in 2009 as a star attraction of roboworld®. But like any aging athlete, time took its toll on Hoops, its accuracy eventually slipping to about 60%. The museum struggled to find replacement parts for the robot, so in 2017 it was upgraded to a new, sleeker robotic arm, now dazzling a new generation.

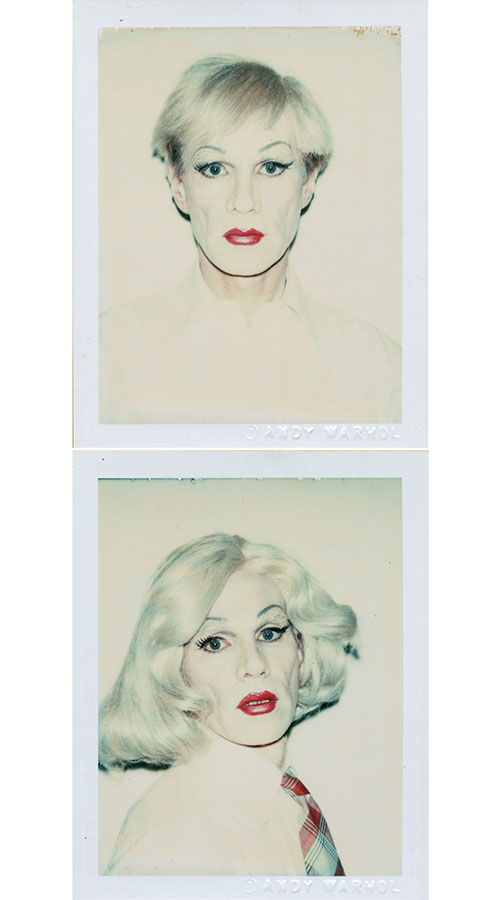

Pinhole glasses, 1950s, The Andy Warhol Museum; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

Warhol’s Pinhole Sunglasses

Andy Warhol was nearsighted, and in the 1950s he tried a new unproven method of corrective vision: pinhole sunglasses, similar to a pair of dark sunglasses with multiple small pinholes punched through each lens. Makers of the eyewear claimed in mass-market advertisements that they would improve vision by strengthening eye muscles, but the method was debunked shortly after Warhol began wearing them. Discovered in the museum’s archives only recently as staff conducted research for Blake Gopnik’s 2020 biography Warhol, the pair of damaged sunglasses was among the final batch of archival material The Warhol acquired from The Andy Warhol Foundation, Inc., in 2014, the same year the foundation liquidated its art collection. A staff member and Gopnik took the lenses to an optometrist in Pittsburgh’s Market Square to learn more about them. It’s likely vanity motivated Warhol to give the eyewear a shot. Around the same time, he began doctoring photographs of himself and had the skin on his nose shaved.

Dan Johnson, Gazelle lounge chair, 1956-1960, Carnegie Museum of Art, Women’s Committee Acquisition Fund

Gazelle Lounge Chair

When you explore Carnegie Museum of Art’s much-loved collection of chairs, what draws you in? Their material or functionality? Based on looks alone, Rachel Delphia, the museum’s Alan G. and Jane A. Lehman Curator of Decorative Arts and Design, says one of her favorites is this whimsical Gazelle chair, named for its gracefully abstracted animal silhouette. California designer Dan Johnson made a series of furniture pieces in which this animal, cast in metal, forms the supporting elements. Can you spot the gazelles? Start at the top, says Delphia, to find the antlers, the elongated faces, and the animals’ stance.

Walking Man by Alberto Giacometti

Since joining Carnegie Museum of Art’s collection as a prize winner in the 1961 Carnegie International, Alberto Giacometti’s bronze Walking Man I has, figuratively speaking, been in constant motion. Standing 6 feet tall and looking alarmingly thin, his forward-leaning posture suggests he has somewhere to go and must keep moving forward. Although the Swiss-born artist’s practice included paintings and printmaking, it was his iconic series of sculptures that moved him to the forefront of 20th-century art. Nearly 45 years after his death, a Giacometti Walking Man statue—one cast from the same lot as the Carnegie’s—was sold to an anonymous bidder for a staggering $104.3 million.

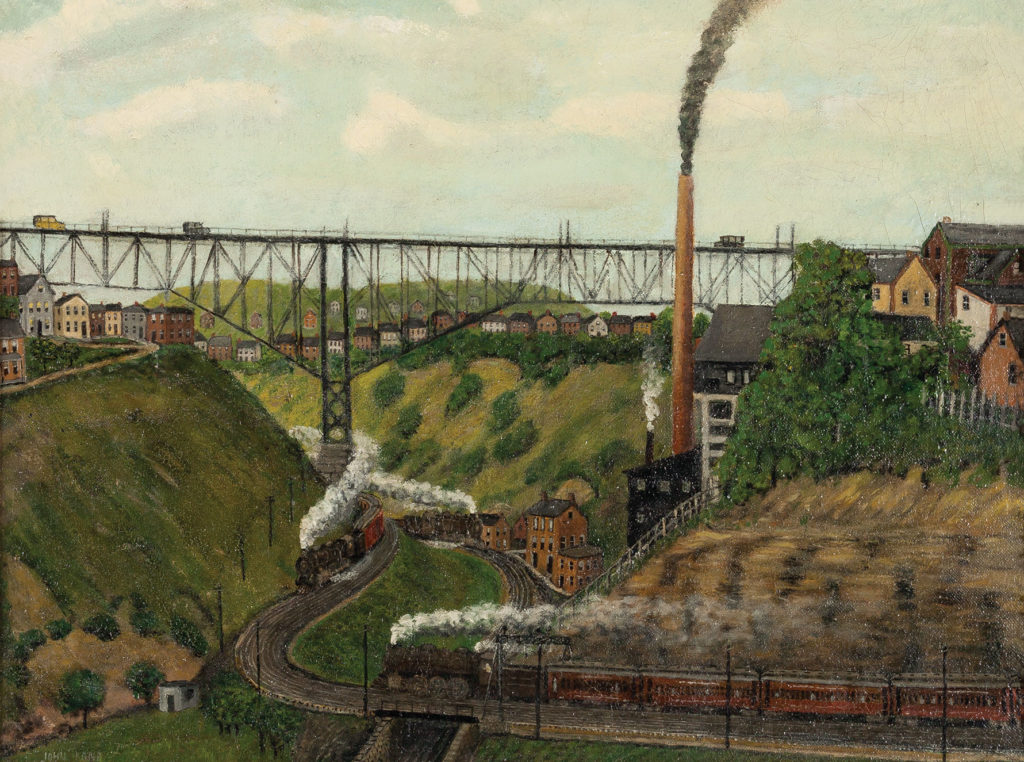

The Cloud Factory

In reality, the Bellefield Boiler Plant is not in the business of producing clouds. Its purpose is much more practical. The three-story, Oakland-based facility was built in 1907 to power and heat the expanding Carnegie Museums and Library. Originally fueled by coal, the plant now runs exclusively on natural gas and is owned and operated by a consortium of eight neighboring Oakland institutions, including universities, hospitals, and Carnegie Museums. Nestled in the valley below Schenley Park Bridge, the building itself is easy to miss. However, the white, fluffy clouds billowing from its tall smokestack—the result of hot water vapor coming into contact with colder air—captured the imagination of then-University of Pittsburgh student Michael Chabon. In his 1988 book The Mysteries of Pittsburgh, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author dubbed the plant the Cloud Factory. And, so it remains in the hearts and minds of local residents.

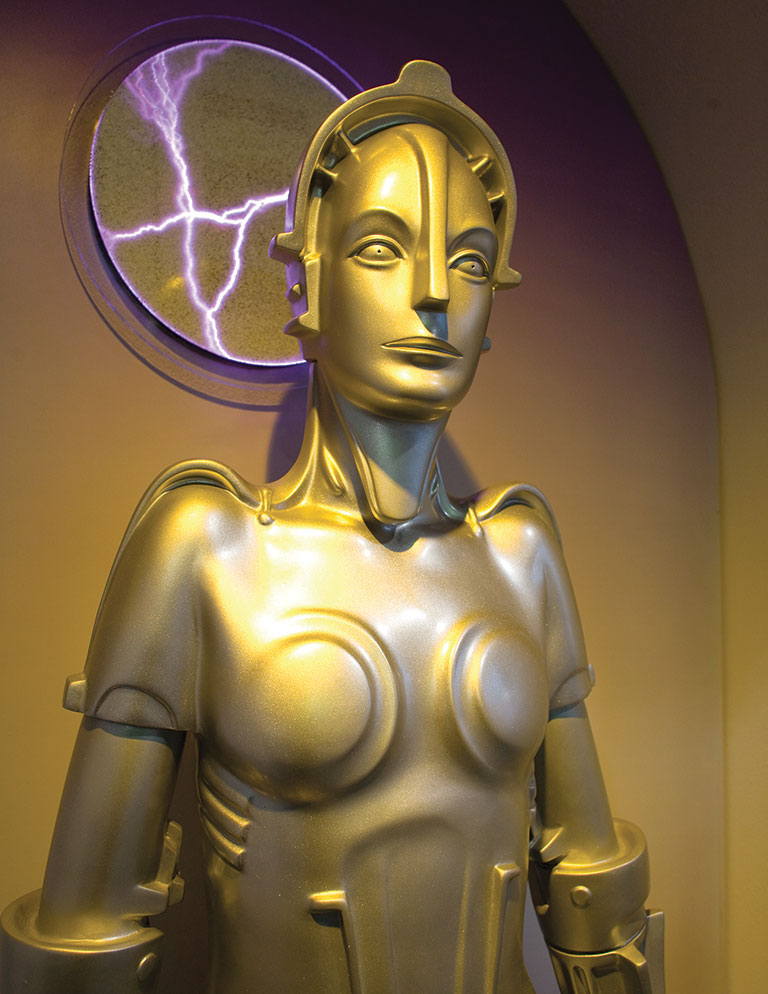

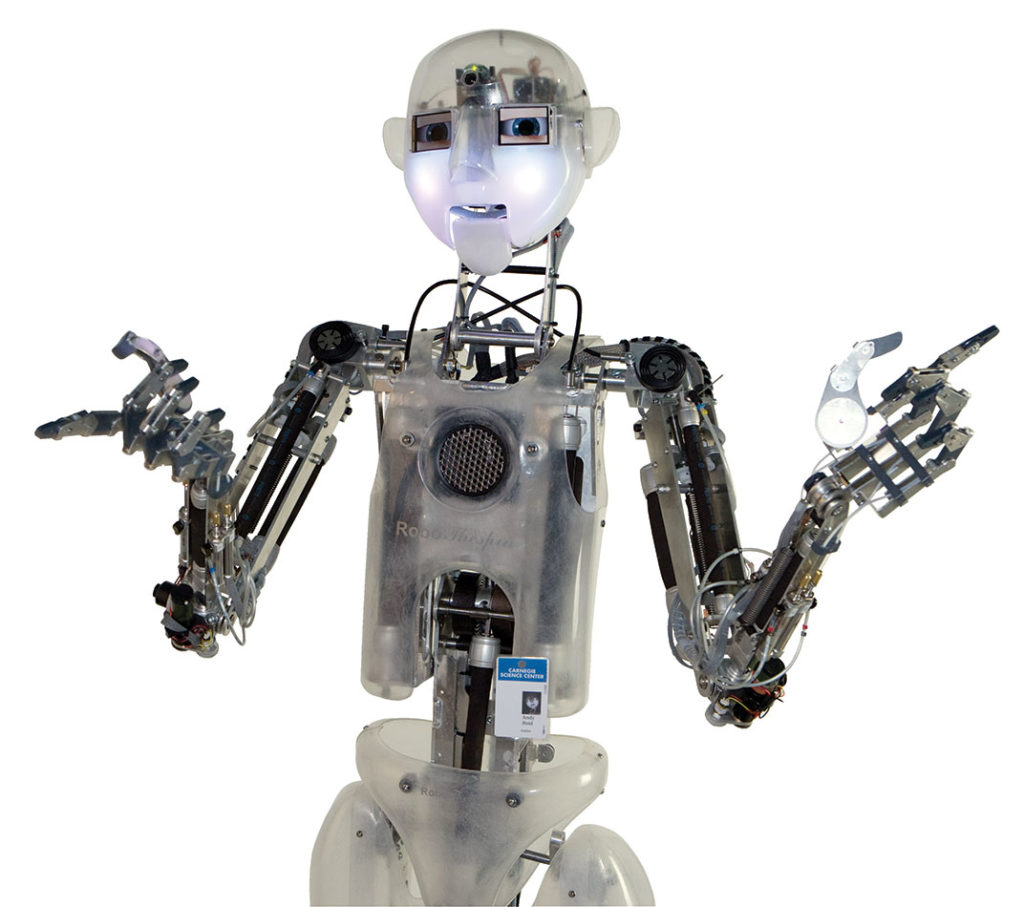

Maria

In Fritz Lang’s 1927 silent German film Metropolis, an industrial magnate bestows upon a tin-plated “man-machine” the face of a real woman named Maria who had stolen the affections of most of the workers in the fictional, turn-of-the-19th-century city. In this futuristic deliberation on the relationship between labor and management, Lang’s Maria looks like a human but lacks any sense of humanity. And, for much of the 20th century, this depiction of robots, however lifelike the rendering, was the norm. In 2009, Carnegie Science Center’s roboworld® provided the first physical home for the world’s most famous imagined robots—Carnegie Mellon’s star-studded Robot Hall of Fame. The replicas on display are a tribute to the fictional machines that helped spark the visions of those who created the real robots that followed. Real or not, Maria remains one of the most powerful female images in film history.

George W. Bellows, Anne in White, 1920, Carnegie Museum of Art, Patrons Art Fund

Anne in White by George Bellows

Best known for his depictions of the bustling urban landscape and boxing matches in the backrooms of bars in New York City, realist painter George Bellows also made masterful likenesses of his wife, Emma Story, and their two daughters, Anne and Jean. In February 2020, Anne’s daughter, Marianne S. Kearney, donated to Carnegie Museum of Art the blue silk sash her mother wore in the 1920 portrait Anne in White, one of six works by Bellows in the museum’s collection. For the last 14 years of her life, Anne lived in Upper St. Clair and would visit the museum to spend time with the portrait, which was her favorite. “In later years, when she showed me and talked about the blue silk sash, it was easy to see that the sight of it took her to a happy time and place when she had the undivided attention of the father she adored,” wrote Kearney in a letter to the museum. “He gave back to her a portrait of a lanky 9-year-old made beautiful with skilled hands and the eyes of love.” Bellows, who was born and raised in Columbus, Ohio, was regarded by many as one of America’s greatest artists when he died at age 42 from a ruptured appendix.

Andy Warhol, Brillo Soap Pads Box, 1964, The Andy Warhol Museum; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

Brillo Boxes by Andy Warhol

In 1964, when Andy Warhol’s Brillo Boxes debuted at the Stable Gallery in New York, collectors and critics were perplexed, and maybe a little annoyed. “Is this art?” they asked. Warhol’s now-famous installation featured 80 plywood boxes, identical in size and shape to the shipping cartons sold in grocery stores, which he and two studio assistants painted and silkscreened with spot-on consumer product logos: Campbell’s Tomato Juice, Kellogg’s Corn Flakes, Brillo Soap Pads, Mott’s Apple Juice, Del Monte Peach Halves, and Heinz Tomato Ketchup. They were virtually indistinguishable from their real-world cardboard counterparts and stacked as if crammed into a grocery store warehouse. The artist envisioned people buying them and walking down Madison Avenue with the boxes under their arms, but they didn’t sell well. The joke, of course, is on the critics: In 2010, a signed Brillo Box sold for $3 million.

Pennsylvania Land Snail

Pennsylvania land snails, which include more than 100 species of both shelled animals and slugs, are found almost everywhere, yet the public knows little about them. They’re important ecologically, providing food for all sorts of mammals, birds, and insects, while they themselves do the critical work of munching on decomposing vegetation. George H. Clapp, a founder of what is now Alcoa and a trustee of Carnegie Museums for more than half a century, collected many things, and shells were a true passion. Shortly after the museum opened, Clapp donated his personal collection of some 300,000 mollusks, with a focus on land snails (including these Mesodon thyroidus from Pennsylvania)—mightily contributing to the foundation of the museum’s collection that now includes nearly 2 million specimens and boasts more land and freshwater snails from the Keystone State than all other U.S. museums combined. Those numbers continue to grow, as curator Tim Pearce and a small band of volunteers work on a definitive census of the state’s land snails.

Astronaut Mike Fincke’s T-shirt

Astronaut and Emsworth native Mike Fincke has logged nearly 382 days in orbit during his three space missions. During those flights, he conducted important scientific experiments, performed critical spacewalks, and enthusiastically waved the Terrible Towel in support of his hometown team, the Pittsburgh Steelers. That towel, along with the “I Love Carnegie Science Center, Pittsburgh, PA” T-shirt he wore while aboard the International Space Station, has since landed in the Science Center’s SpacePlace exhibit, which also features the hometown hero’s flight suits, gloves, watches, flip charts, and mission books. As a kid growing up not far from the city, Fincke spent endless hours in the Buhl Planetarium learning—and dreaming—about the stars. Now, he’s hoping to inspire the next generation of explorers to follow their own dreams.

The Neapolitan presepio

It’s an elaborate Italian street scene seemingly captured mid-breath. Carnegie Museum of Art’s Neapolitan presepio shows merchants selling their wares, a marching band in full stride, animals mingling among the residents, both human and heavenly—some seemingly oblivious to the newborn Christ child and his parents. Popularized in the 18th century, presepi were often commissioned by wealthy Neapolitans to celebrate one of the most important holidays in the Catholic faith, situated within present-day Naples. The craftmanship of the day remains impressive some 300 years later, from the textiles used—including silk damask and denim twill—to the tiny props of cheeses molded from clay and fruits and vegetables sculpted in wax. For the past 65 years and counting, the day after Thanksgiving marks the unveiling of this annual exhibition. Following tradition, every year curators rearrange the elements to create the panorama anew. At more than 200 pieces, it’s one of the most complete sets in the world.

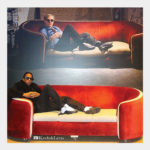

The Red Couch

Once a fixture at Andy Warhol’s Silver Factory, the now-legendary red velvet couch first made famous in one of the artist’s underground films was trash turned treasure. It was discovered in early 1964, abandoned on the curb in front of the YMCA located across the street from Warhol’s original studio on East 47th Street. No doubt it was destined to become rubbish until Warhol collaborator Billy Name, the man who literally put the silver in the Silver Factory, recognized its charm and, utilizing its rollers, simply pushed it into an elevator to get it into Warhol’s fourth-floor space. The couch soon became the preferred place for overnight guests to crash, and a favorite focal point for many of Name’s well-known photographs. A few years later, the couch was lost in much the same way it was found: The Silver Factory was on the move to a new location in Union Square, and the red icon was left unattended on the curb, never to be seen again. Nowadays, visitors to The Andy Warhol Museum are greeted by a faithful reproduction in the museum’s entrance space. The couch continues to beckon the famous (rap mogul Jay-Z is pictured) and those yet to claim their 15 minutes to take a seat—and a picture.

The Observatory

On select clear nights, visitors to the Henry Buhl, Jr. Planetarium & Observatory at Carnegie Science Center can go to the fifth-floor observation deck, peer through a Meade LX200 Schmidt-Cassegrain telescope, and get an up-close view of amazing celestial wonders. If the stars and planets are aligned, they may even catch a glimpse of Saturn’s rings or the surface of the moon. During the SkyWatch program, amateur stargazers begin the evening with a virtual view of the night sky inside the newly updated Buhl Planetarium. Then they head up to the observatory to try and spy the real deal in the night sky. Science Center staff are on hand to chat about what they see through the high-powered 16-inch telescope that’s provided, or guests are invited to bring their own telescopes for an unforgettable night beneath the stars.

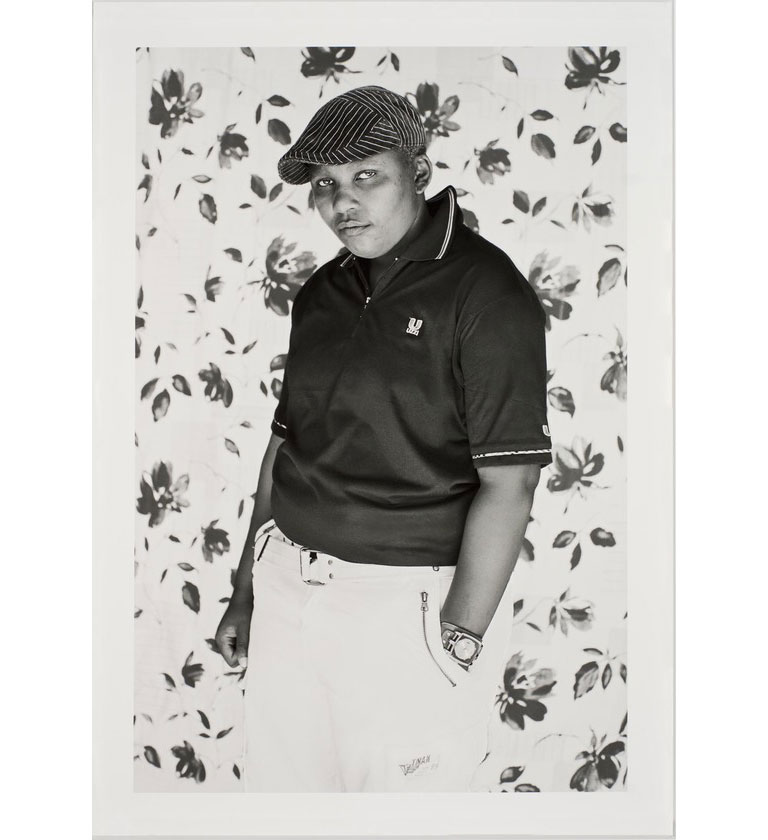

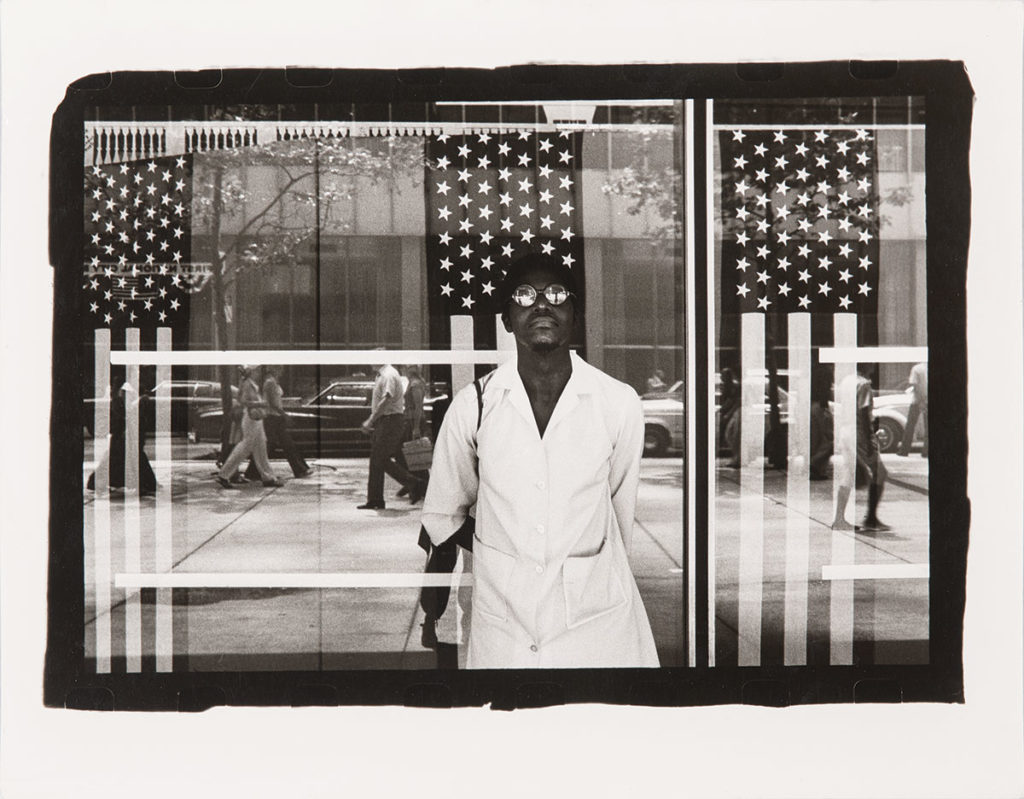

Zanele Muholi, Zimaseka “Zim” Salusalu, Gugulethu, Cape Town, 2011, Carnegie Museum of Art; A. W. Mellon Acquisition Endowment Fund © Zanele Muholi, Courtesy of the artist and Yancey Richardson Gallery

Portrait of Zimaseka “Zim” Salusalu by Zanele Muholi

A self-described visual activist, Zanele Muholi of South Africa has dedicated their career to promoting awareness of their country’s LGBTQI+ communities. Although South Africa legalized same-sex marriage in 2006, discrimination and violence against LGBTQI+ individuals remains widespread. Muholi’s photographs and the accompanying testimonies form a growing record of people risking their lives by living authentically in the face of oppression and persecution. “This is not art; this is life,” says Muholi. “Each and every photograph is someone’s biography.” Portraits from their series Faces and Phases, now numbering more than 300, appeared in the 2013 Carnegie International, including this one, which is part of Carnegie Museum of Art’s collection.

Van de Graaff Generator

Just about every week during the school year, educators for Carnegie Science Center’s Science on the Road program perform science shows for a different elementary and middle school. In a typical year, the program reaches some 170,000 students. In one popular hair-raising lesson, educators pull out all the stops with a machine that makes the same kind of electricity that lightning makes: static electricity. An educator waves a silver wand toward a sputtering Van de Graaff generator, causing a white electric bolt to leap from it with a loud crack, eliciting “oooohs” from the audience. Then, to illustrate how lightning travels, students form a small line—the chain of pain—and link pinky fingers. The educator stands on a milk crate so that she isn’t grounded, and as she rests her hand on the generator, her hair stands on end. Laughter erupts. When she touches elbows with the first student in the line, a spark flies, and soon every child in the line pulls away from the surprise of the shock.

Pangolin

Despite their lizard-like appearance, pangolins are mammals that are often referred to as scaly anteaters. They have no teeth and lap up social insects like termites and ants with their sticky tongues—tongues that can grow as long as their bodies minus their tails. Pangolins can be covered in up to 1,000 protective scales—which, like human fingernails, are made of keratin—and their natural defense is to roll up into a ball. But there’s one predator they can’t seem to escape: humans. The weirdly wonderful pangolin is the most illegally trafficked animal in the world—mainly in Asia and in growing numbers in Africa—hunted by poachers for their meat and scales, which are used in traditional medicine practices. This taxidermy pangolin, most recently on view in Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s landmark exhibition We Are Nature: Living in the Anthropocene, is one of 27 in the museum’s care.

Dental Models, ca. 1982, The Andy Warhol Museum; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

Warhol’s Dental Molds

Andy Warhol was a famous pack rat, stashing away direct-mail flyers, greasy wigs, and an assortment of other items he came across in his daily life. But even Warhol experts weren’t sure what to make of all the dental models he kept in his collection of random stuff. All they know is that one summer day in 1982, the artist and his assistant Jay Shriver walked into Columbia Dentoform Corp. on East 21st Street in New York City. They handed over $484 and walked out with an odd assortment of dental forms. Matt Wrbican, the late chief archivist for The Andy Warhol Museum and Warhol scholar extraordinaire, put the 144 objects on display at the North Shore museum in 2004. He said that it was a mystery why Warhol collected the models, some with teeth missing, others with removable teeth or no teeth at all. Wrbican wasn’t sure why Warhol was so fascinated with the curiosities coated in a soft aluminum-pewter sheen, but he speculated that they were related to the artist’s fascination with human anatomy, and his own physical imperfections.

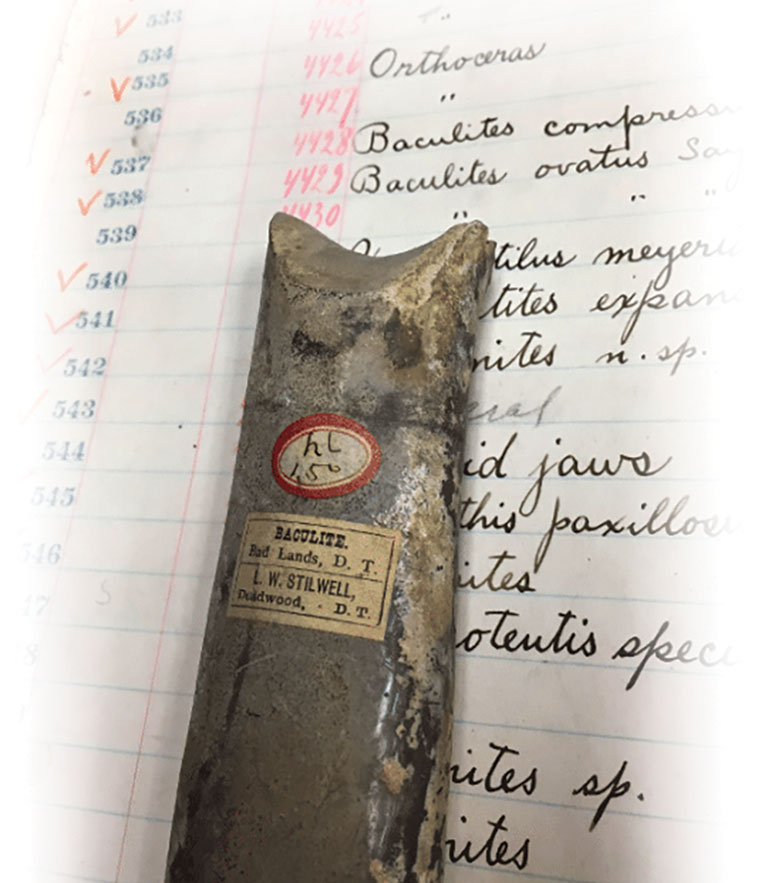

Baculites fossil with L.W. Stilwell label.

The Baron de Bayet Collection

Having gained infamy as the place where Wild Bill Hickok met his maker thanks to a gunshot in the back, the Deadwood, Dakota Territory, was not a place for the faint of heart. And yet, that’s where a frail, studious-looking Lucien Stilwell decided to settle in 1879. Looking to outrun a yellow fever outbreak, Stilwell headed west. By 1890, he had established his own thriving business selling fossils and minerals unearthed in the Badlands to world-class collectors like Baron de Bayet of Belgium. By the turn of the century, Bayet had amassed an assortment of 130,000 invertebrate fossils from more than 50 fossil collectors, 15 European countries, and 10 states—a collection sought by museums throughout Europe, Great Britain, and the United States. William Jacob Holland, Carnegie Museum’s second director, told Andrew Carnegie that the acquisition “will make our museum one of the Gibraltar’s of paleontological science in the world,” and it was indeed an early gem of the museum, with specimens exhibited in the dinosaur halls of 1907 and today. In a multiyear project, the museum’s section of invertebrate paleontology is now taking a fresh look at this somewhat hidden treasure.

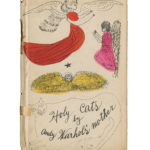

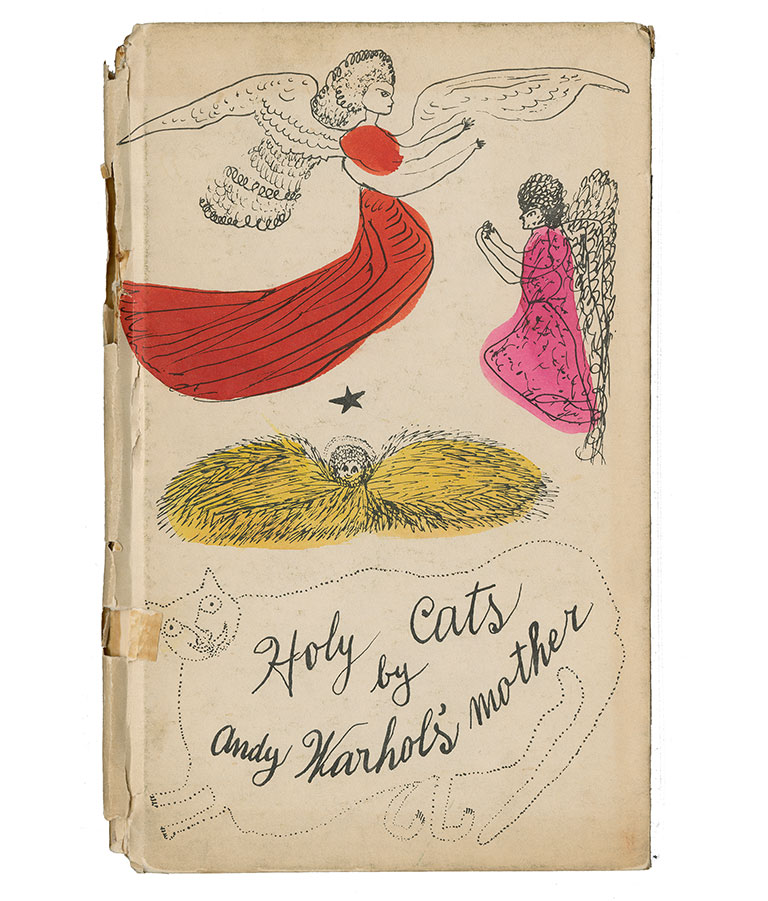

Julia Warhola, Holy Cats by Andy Warhol’s Mother, 1960, The Andy Warhol Museum; Gift of Angela Heizmann Gilchrist in Memory of Catharine Stewart Dives

Holy Cats by Andy Warhol’s Mother

Having artistic talent herself, Julia Warhola recognized her youngest son Andy’s abilities from a young age and encouraged him to pursue his passion, including sending him to Saturday art classes at Carnegie Museum of Art. When Warhol moved to New York City in 1949, it wasn’t long before Julia joined him, and he began enlisting her to add her unique handwriting to hundreds of his drawings, advertisements, and book illustrations. Julia also loved to draw, with cats and angels as her favorite subjects. In 1956, the pair made a book about their cats, 25 Cats Name Sam and One Blue Pussy, featuring illustrations combining Andy’s blotted line drawings and calligraphy by Julia. When she left out the “d” in the book’s title, her son loved it and opted to keep it anyway. Four years later, Julia wrote and illustrated Holy Cats by Andy Warhol’s Mother.

A print of Alice Patrick’s Women Do Get Weary, but They Don’t Give Up hangs in the Braddock municipal building.

Photo: Bryan Conley

The Art Lending Collection

It was 1991 when artist Alice Patrick’s mural Women Do Get Weary, but They Don’t Give Up first loomed large on the National Council of Negro Women’s Los Angeles building. Some 20 years later, a smaller yet still powerful framed print of the work hung in the Braddock municipal building. Thanks to the Art Lending Collection, Women Do Get Weary is one of more than 160 artworks available to anyone with an Allegheny County library card to borrow, display, and enjoy for up to three weeks at a time—changing the dynamic of who gets to interpret and experience art. Now funded by the Heinz Endowments, the collection was the brainchild of Braddock-based artists Dana Bishop-Root, Leslie Stem, and Ruthie Stringer. Their idea took root as their contribution to the 2013 Carnegie International, with all exhibition artists contributing original artwork for the collection. Since then, it has grown to include donations from private collections, original works from local artists such as fellow Braddock resident Jim Kidd, people imprisoned at the South Fayette Correctional Institution, and framed posters of classics.

Saturday Art Classes

They’ve survived the Great Depression, a world war, the rise and fall of art movements from Cubism to Pop, and now a pandemic. For more than 90 years, Carnegie Museum of Art has continued the tradition of working with Pittsburgh’s young artists to help them hone technical skills and foster imagination at Saturday art classes. While the name of the classes changed through the decades—Tam O’Shanter, Palette, and, currently, The Art Connection—the artistic discovery they’ve awakened in generations of students, often within the same family, has remained the same. For a small number of students—Annie Dillard, Andy Warhol, Jeff Goldblum, and Mel Bochner, to name a few—the program was an early step on the way to international renown. For many others, the classes have been a magical family tradition.

Photo: Bryan Conley

Sol LeWitt’s Wall Drawings

The colorful geometric drawings that grace the staircase leading up to Carnegie Museum of Art’s Scaife Galleries are hand-painted. Just not by the artist himself. A pioneer of conceptual art, Sol LeWitt took a decidedly hands-off approach when it came to putting brush to canvas (or wall). He created art by developing an idea and producing written instructions for other artists, many trained in his studio, to carry out. He believed the input of others was part of the process, and even children have contributed to some of his public works in schools. The museum’s pair of side-by-side wall drawings were originally painted in the mid-1980s—LeWitt designed the second work once he saw the location of the first. Twenty-some years later, their colors faded by the natural light streaming in through the large window to the Sculpture Court, the murals were repainted by museum staff joined by local artists. The project took on new significance when the 78-year-old LeWitt died shortly after the repainting was completed in 2007.

Carnegie Science Award

For 25 years, Carnegie Science Center has recognized the region’s shining stars in science and technology—ingenious students, inspiring educators, and industry-changing entrepreneurs—at its annual Carnegie Science Awards. A panel of past awardees and industry leaders selects winners whose contributions have led to significant economic or societal advancements in western Pennsylvania. With the support of committed sponsors, a new addition for the 2021 awards is the recognition of champions in sustainability and science, technology, engineering, and math equity.

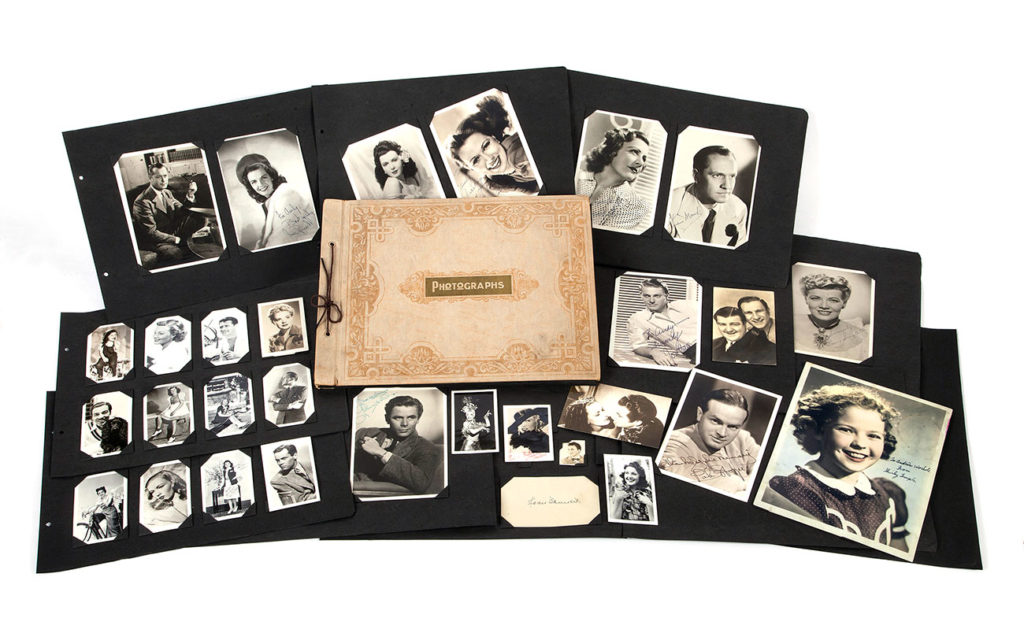

Photograph album (Andy Warhola’s childhood movie star scrapbook), ca. 1938-1941 © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc

Andy Warhol’s Movie Star Scrapbook

Like a lot of kids growing up during the Great Depression and World War II, Warhola brothers Paul, John, and Andy would find refuge in the three movie theaters near their South Oakland home. Paying a nickel or two, they knew that as soon as the lights dimmed the screen would be illuminated with the celebrities of the day—Joan Crawford, Henry Fonda, Jane Russell, and Mae West among them. Andy was particularly star-struck. He convinced Paul to write letters requesting signed photos, and Andy would meticulously add every new arrival to his rapidly expanding scrapbook. The album filled to more than 30 pages, but the 1941 hand-colored photo signed, with typo included, “To Andrew Worhola, from Shirley Temple” took center stage, until at some point it was removed and later found in Time Capsule 61.

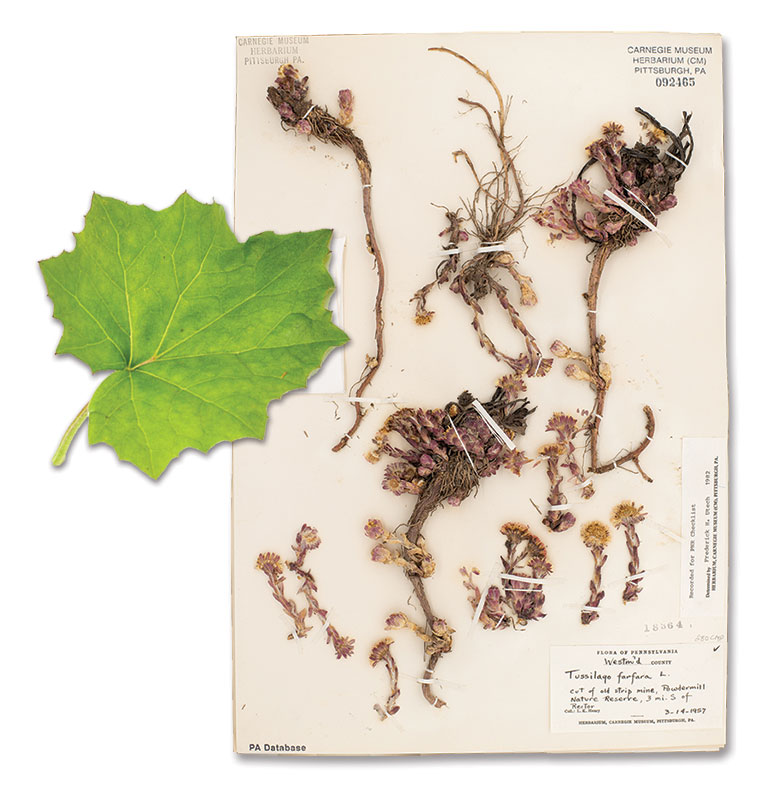

Coltsfoot, Then and Now

On March 14, 1957, botanist Leroy Henry walked through the woodlands around Powdermill Nature Reserve, just one year after it was established as Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s field station, and collected coltsfoot, known scientifically as Tussilago farfara. To the untrained eye, the plant with yellow flowers might look like a common dandelion. But Henry, a former longtime curator of botany, knew what he had. Native to Europe, North Africa, and Asia, the coltsfoot has flowers that bloom in early spring, followed by leaves that look like—you guessed it—a colt’s foot, and they last well into the summer, making it a good species for research. In fact, the coltsfoot is among the first plants to be used in a pioneering study published in 2006 using herbarium specimens. In Southern Quebec, they found that coltsfoot bloomed 15–31 days earlier in recent decades, compared to pre-1950. Earlier blooming was strongly linked to climate change. It’s one of hundreds of plants highlighted in Collected on This Day, a weekly blog by Curator of Botany Mason Heberling that’s funded by the National Science Foundation and features the important scientific and cultural stories of the specimens in the museum’s herbarium, making clear why natural history collections help us understand the world around us.

Binary Flip Clock

Visitors eating lunch in Carnegie Science Center’s RiverView Café may look up at what appears to be a modern wall sculpture made up of many plates. But wait. Those square plates are moving, flipping one after another, perfectly in sync. The plates, which are keeping the exact time, are the mechanical pieces of the largest binary flip clock ever created. Doug DeHaven, a mechatronics engineer at the North Shore museum, wanted to make a timepiece that was both visually interesting and functional for a new wall erected as part of the addition of the PPG Science Pavilion. But he didn’t want a clattering clock with noise that would disturb staff. So he dreamed up a mechanical creation consisting of three rows representing seconds, minutes, and hours—and, of course, a splash of artistry. Each column includes graphics that represent different ways humans count—from military time to Roman numerals, American Sign Language, and the programming language Scratch.

Mallard Duck Decoys

North American hunters have used decoys for centuries. Indigenous Americans fashioned them from reeds, clay, and stuffed skins to lure migrating birds within range of their arrows and spears. European settlers observed the effectiveness of what were often quite rudimentary decoy rigs, such as duck skins wrapped over floating logs arranged to look like a wading bird and adopted the practice. By the early 19th century, both commercial and sport hunters were using carved wooden decoys. However, some hunters preferred real skin decoys known as “stuffers,” like these made by Whistler Brothers. They were popular during the Depression and donated to Carnegie Museum of Natural History in 1980 by benefactor Edward O’Neil. Made from farm-raised mallards, the skins were wrapped around cork bodies and heavily varnished so that they float, and lead weights were added to the undersides to allow them to float upright. “I always thought this was a cool form of taxidermy begun by Indigenous people and still used to some extent today,” says Stephen Rogers, collection manager for the section of birds and a taxidermist.

Dippy’s Scarves

Diplodocus carnegii, the long-necked star of Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s world-famous collection of Jurassic giants, got its own public sculpture in 1999, celebrating a century since he was unearthed at Sheep Creek, Wyoming. That winter, Janice Heagy, former Carnegie Museums staff member, handmade Dippy a Jurassic-sized red and green scarf to mark the holiday season, kicking off a now-beloved Pittsburgh tradition—dapper Dippy dressed for the occasion: Steelers playoff football, Pitt move-in day, and LGBTQI+ Pride Month, to name a few. Dippy’s accessories have grown in number over the years to the point that he now has his own closet at the museum stuffed with at least 15 oversized scarves, lovingly made by both staff and volunteers. There’s also a top hat and bow tie, a mortarboard, and, most recently, several face masks. And every St. Patrick’s Day, Dippy celebrates the wearing of the green with his longest and most popular adornment measuring 18 feet long!

Photo: Joshua Franzos

T. rex Holotype

Despite their relatively puny arms, Tyrannosaurus rex had the jaw-dropping power of a 40-foot-long, 5-ton body. And their spiky teeth were sharp, efficient, and deadly. Roaming what is today the western U.S. and southwestern Canada in search of food, the meat-eating T. rex ruled some 68 to 66 million years ago during the late Cretaceous Period. But it wasn’t until 1902 that the holotype—the scientific name-bearing specimen and the one to which all others must be compared—was unearthed at Hell Creek, Montana. At the turn of the century, the competition among museums to discover and display dinosaur fossils was fierce. Young fossil hunter Barnum Brown was hired by New York’s American Museum of Natural History to lead its charge, and he did not disappoint. Over three years, he unearthed what was at the time a whole new species of dinosaur. But it didn’t take long before Brown moved on to bigger and better findings. His 1908 excavation of a more complete T. rex skeleton prompted the museum to move the holotype into storage, and in 1941, with a dwindling research budget, the American Museum sold the T. rex holotype to Carnegie Museum of Natural History. The price? $7,000 ($130,000 in today’s currency) for what is by definition the first fossil of the world’s most famous dinosaur.

Richard Serra, Carnegie, 1985, Given in memory of William R. Roesch by his wife Jane Holt Roesch © Richard Serra/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York | Photo: Tom Little

Carnegie by Richard Serra

As the 1985 Carnegie International approached, sculptor Richard Serra was mired in controversy surrounding his public sculpture Tilted Arc. Some New Yorkers weren’t happy about having to negotiate its curving wall of raw steel outside the Jacob K. Javits Federal Building in Lower Manhattan. It prompted a local court battle to have the artwork removed and a national debate about the purpose and placement of public art. But when a massive crane arrived on Forbes Avenue in front of Carnegie Museum of Art to position the four Cor-Ten steel panels that would lean against each other to form Serra’s 40-foot tower titled Carnegie, no one voiced any concerns or objections. The reaction was quite the opposite. People were intrigued by the sculpture’s interesting edges and angles, not to mention its weathering patina. Serra’s Carnegie emerged as one of two winners of the prestigious Carnegie Prize and it still stands near the museum’s front door. Its title conveys the industrial legacy of art in Pittsburgh by recalling both the museum and its founder, Andrew Carnegie, whose U.S. Steel Corp. invented Cor-Ten steel.