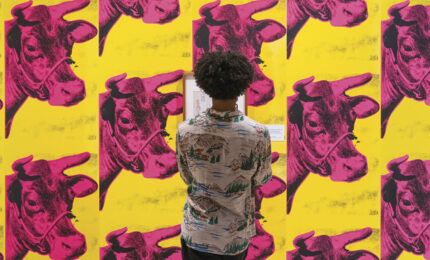

Photo: Martha Rial

As an Army brat and child of an Ethiopian immigrant mother and African American father, Michelle King says she’s learned to be comfortable “in the spaces in between.” The educator uses it to her advantage, bringing people together around issues of social justice. King calls herself the Learning Instigator: “I feel they’re my superpowers—as a middle school teacher, as forever being curious and having a sense of wonder and love of learning.” She works with Carnegie Museum of Art on the Empowered Educators Series to help area educators and schools talk openly in the classroom about issues of race and equity.

Q: Why did you decide to leave the classroom?

A: I felt like we needed to answer different kinds of questions. Not questions that were answers to a test, but what do humans need to learn now. I could see the divisiveness, separation, and segregation in society, and I wanted to be in community differently. I felt compelled to move from the classroom and become a full-time troublemaker.

Q: What kind of trouble are you causing?

A: I often equate the work I do to farming. It’s cultivating the soil. Creating the conditions for the beloved community—love, equity, and justice—to grow and be harvested. This work means we’re dependent on each other, each and every one of us.

Q: What attracted you to the Empowered Educators Series?

A: It’s an impressive group of partners: Center for Urban Education, Western Pennsylvania Writing Project, Remake Learning, and Carnegie Museum of Art. It does matter that it takes place at the museum. Carnegie Museum of Art has its history, a weight, a gravitas. So having conversations around race and equity, it’s like, OK, we’re getting serious about talking about things. I came deeply out of curiosity.

Q: Is it work that never really ends?

A: Generationally and historically, we’re taught to be ashamed about race. To be defensive. Our practice is heavy on avoidance. I see these political times as a real gift because they force us to confront what has always been present. It’s just lifted a lid on what’s been there, what we haven’t talked about, but what we do notice. Scholar Beverly Tatum asked the question, “When do you notice race in school?” Almost exclusively it’s by elementary age. But when do we actually get to talk about it or be in real discourse? This is an opportunity to be able to hold those discussions, teacher-to-teacher, so they build the capacity to hold them in their classrooms. The thing is, those conversations are happening anyway. We might squelch them, we might avoid them, but it’s not like they don’t surface. They show up in our art, they show up in our history, they show up in our literature. For me the real aspiration is to take away the shame and embarrassment and develop the practice of being in discourse when we have challenging topics and still stay in relationship with each other.

Q: Is art a useful tool in this journey?

A: Absolutely. Part of the aspiration for the program is teachers would see the museum as an extension of their learning space, to make it their own, and I think it’s embedded. How might teachers come back and use the exhibits, how might teachers see the museum as a place of learning to have all kinds of conversations? When I first started teaching, I used

to think schools were neutral, but every place has a gaze with embedded values. Carnegie Museum of Art has a gaze that it’s designed from. At the museum, students and teachers can talk together about who got to create what’s on view, what was it intended to do, how is power held, whose voices are included, whose voices are missing, and what impact that has on the past, on current times, and on the future.

Q: Do you think students are hungry for these conversations?

A: Yes, it’s part of their life. I remember a student told me, “I can’t wait to start my life.” I told her this is not a starter kit, this is your life. In some ways, kids see school as not real. Yet schools are some of the first places we learn to be in community. Our desire to make things almost antiseptic to kids is a disservice. It’s developmentally appropriate for young people to take risks and get things wrong. When dealing with topics of race, bias, inequity, how do we help them learn when the stakes aren’t so high? How do we help them practice their way forward? How do we teach them that sometimes, even with good intentions, we cause harm?