In the early days of The Andy Warhol Museum, before there was a building to call a museum, there was Matt Wrbican.

Among the first handful of people hired in 1991—four years after Andy Warhol’s death and three years before The Warhol officially opened its doors—Wrbican took on the role of assistant archivist and was immediately dispatched to New York City.

Under the direction of The Warhol’s first director and curator, Mark Francis, and with guidance from The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, he was charged with sorting through all the things—large and small, ordinary and extraordinary, weird and wonderful—that Warhol left behind.

And there was a lot.

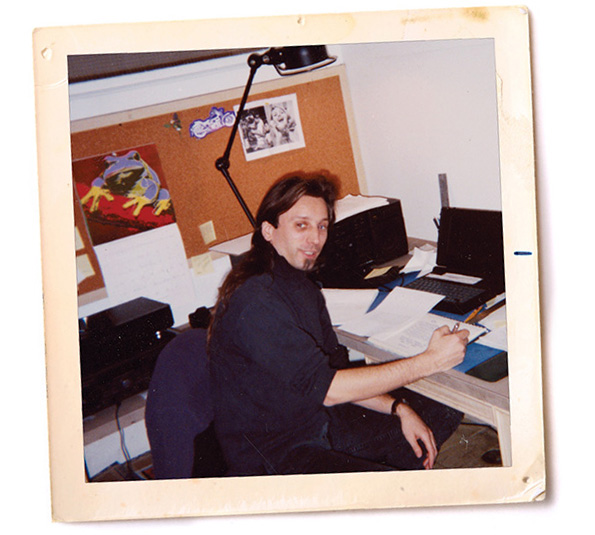

The early days: Matt Wrbican at The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts prior to the 1994 opening of The Andy Warhol Museum.

Working alongside the artist’s former assistant, Jay Shriver, and his colleagues from the foundation, Wrbican spent the next two years holed up in Warhol’s final studio in Midtown Manhattan, describing, inventorying, counting, and constantly making lists. In his free time, he read as many books about Warhol as he could, to help him understand the materials that he was working with and their potential significance. Every so often something unexpected would happen and break the routine.

“One day I was poking around,” Wrbican recalls, “and I found a shortbread cookie tin. I shook it. It wasn’t empty, but it didn’t sound like cookies. I opened it and found a large manila envelope. I opened that and found a business-size envelope, and inside that was a truly shocking discovery. I mean, I was shaking.”

Wrbican had discovered a stash of $100 bills—140 of them to be precise—with the bank band still wrapped around it. “I can’t believe it. You found it!” Wrbican recalls Shriver exclaiming. “We all wondered where he kept the stash!”

Shriver went on to explain that each time Warhol asked someone to run an errand to buy chocolate or books or pay for Xeroxes or film processing, he would peel off a crisp $100 bill.

The shortbread cookie tin where Warhol stashed Factory hand money and religious items owned by Warhol’s mother, Julia.

Sharing enlightening tales from the Warhol Archive was part of Wrbican’s job from the beginning of what blossomed into a remarkable 26-year tenure at The Warhol. Eventually becoming chief archivist, Wrbican wrote and traveled extensively in support of blockbuster exhibitions held at The Warhol and in galleries throughout the world. He also curated approximately 40 smaller, more intimate shows that were fueled by interesting tidbits he extracted from the Archive.

Although recently retired due to illness, Wrbican has been working with staff at the museum on a book inspired by both the Archive and his knowledge as its longtime archivist—A is for Archive: Warhol’s World from A to Z, scheduled to be released in the spring of 2019.

In it, Wrbican sets the scene for Warhol’s personal reflections on the now-legendary opening party that kicked off the artist’s first solo museum exhibition in the U.S. The 1965 show at the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia was essentially a retrospective of Warhol’s Pop work, and it made an impression.

“The massive press preview the night before gave warning of the anticipated size of the crowd, and [curator] Sam Green decided it was imperative to remove most of the paintings from the gallery walls to safeguard the art,” Wrbican wrote about the exhibition.

“The wisdom of this was proved the following evening when Warhol arrived with his film Superstar Edie Sedgwick, Green, and others to find a mob of thousands of screaming art fans at the ICA.

The Archive contains many items related to Warhol’s dachshunds, Amos and Archie, including dog sweaters, vaccination records, licenses, veterinary bills, and photographs; Warhol’s striped, sailor-style shirt he started wearing in 1965 after devoting himself to making movies.

“Warhol and his entourage were forced to climb a dead-end staircase to avoid the crush, from which they autographed Campbell’s soup cans before escaping through a hole cut into the ceiling above the stairs. Warhol reflected on the experience in amazement. ‘I’d seen kids scream over Elvis and the Beatles and the Stones—rock idols and movie stars—but it was incredible to think of it happening at an art opening … But then, we weren’t just at the art exhibit—we were the art exhibit, we were the art incarnate.’”

Wrbican also fills us in on Warhol’s obsession with all things 3D, such as stereopticon cards, anaglyphs, lenticular and polarized images, and holograms, as well as the viewers and glasses that go along with them.

Ten years before the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., presented its enormous and much-talked-about exhibition Warhol: Headlines, Wrbican examined the same subject in a smaller show in The Warhol’s Archives Study Center. It was his research that helped tease out the fact that Warhol was a master chronicler of his time—more than any other artist.

“Matt has written an incredible amount and has been published in numerous books and journals,” says Abigail Franzen-Sheehan, director of publications for The Warhol and editor of A is for Archive. “This project makes available the many unpublished texts he wrote for exhibitions and other purposes over two decades.” Its structure was inspired by Warhol’s 1950s alphabet books.

A selection of Julia Warhola’s hats.

Three years in the making in collaboration with Yale University Press, the compilation is packed with new photography from The Warhol Archive and promises to unravel a few mysteries, blow up a myth or two, and highlight a few never-before publicly displayed objects.

“It’s been one of the most exciting things I’ve ever worked on,” Wrbican says. “It was a great pleasure to look back on the work and get reacquainted with it.”

The making of a Warholic

For Wrbican, getting acquainted with both the job and the artist has been the real plot twist of his career. “For an archivist,” he explains, “my background is really unusual in terms of academic degrees. I didn’t study library science. At Carnegie Mellon, I processed a collection for the university archives, so I had the experience. My degrees are in fine arts, and I think that combination helped me get the job. When I was hired, I was just finishing a job at Carnegie Museum of Art as assistant to the exhibition coordinator for the [1991] Carnegie International.”

Matt Wrbican examining the contents of a Time Capsule. Photo: Tom Altany

As for the artist himself: “I knew his work generally,” Wrbican says of Warhol, “but I wasn’t any kind of an expert.”

The two men are now and forever inextricably linked.

“It was a perfect match,” says The Warhol Foundation’s Neil Printz, editor of The Andy Warhol Catalogue Raisonné, a multi-volume series on Warhol’s complete artworks. “Like Warhol himself, Wrbican is an artist, a graduate of Carnegie Mellon University [known as Carnegie Tech in Warhol’s day], and a native son of Pittsburgh.”

Just how perfect became more and more evident as Wrbican found his footing—literally and figuratively—in the Archive. A sense of stability and confidence made Wrbican a valuable resource, and quickly earned him a reputation among “Warholics” as the archival detective-in-residence at the museum.

“I think it’s one of the most amazing things when an archivist totally internalizes the corpus of material he’s dealing with and knows it inside out,” says Printz. “At the Catalogue Raisonné, we were interested in figuring out how Warhol did what he did. Matt was right there with us, for example, helping us find the stencils for the Campbell’s Soup paintings. He was interested and curious to figure how Warhol worked, how he made those incredibly brilliant, revelatory paintings. It wasn’t just stuff for Matt—it was living material, it was both concrete and vivid.”

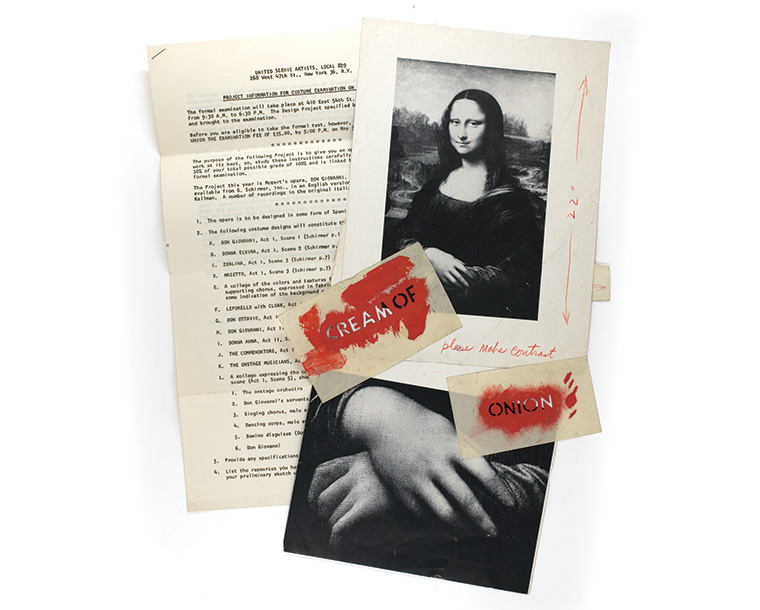

Warhol’s source materials for his Mona Lisa paintings, soup can stencils, and United Scenic Artists’ examination instructions for theater costume design work from Time Capsule 79, ca. 1962–63.

“At the Catalogue Raisonné, we were interested in figuring out how Warhol did what he did. Matt was right there with us, for example, helping us find the stencils for the Campbell’s Soup paintings. He was interested and curious to figure how Warhol worked, how he made those incredibly brilliant, revelatory paintings. It wasn’t just stuff for Matt—it was living material, it was both concrete and vivid.”

– The Warhol Foundation’s Neil Printz

Most notably in the Archive are Warhol’s famed Time Capsules, all 610 of them, mostly cardboard boxes plus 40 filing cabinet drawers and one large trunk. From 1974 until his death, Warhol always had a cardboard box within reach. At first they served a practical purpose as he prepared to move his studio, but then they became something else: his largest serial art project.

According to Fred Hughes, Warhol’s longtime friend, business associate, and executor, Warhol’s intent was to display them in total on a large array of shelves and then sell each Time Capsule separately. Originally, he was going to price them at $100 a box, but he started thinking $4,000–$5,000 was more like it. Although buyers would be able to choose their “capsule,” they could not peek inside until after the sale was final. With an average of 800 items inside, it was a crap shoot: one box could include an original Warhol artwork while another could be stuffed to the brim with magazines and newspapers.

Today, they all live in the Archive, and Wrbican, guiding a small team of catalogers, including current Warhol archivist Erin Byrne, has painstakingly documented their contents over the course of decades. It’s quite a process, which Wrbican, Printz, and Warhol’s longtime friend and studio manager, Vincent Fremont, started in the eight months leading up to the museum’s 1994 opening.

“Since Warhol didn’t write a lot down, there’s a great deal that we don’t know about him. Even his published diaries only cover the last 10 years of his life. The Time Capsules are windows into who he was, what he was doing, where he was going, and who he knew.”

– Matt Wrbican, longtime Warhol Archivist

Each Friday morning they unsealed a new box and got to work. Each item in a particular box was identified, described, and categorized. The most interesting objects were photocopied and photographed. Later, in Pittsburgh, they were repacked in acid-free folders and protective Mylar sleeves. The ultimate goal was to not only provide a detailed description of each item but also offer insights about where an object came from, what its purpose was, and what role it played in Warhol’s life. Although all of the Time Capsules have been opened, staff are still working today to photograph and catalog their contents.

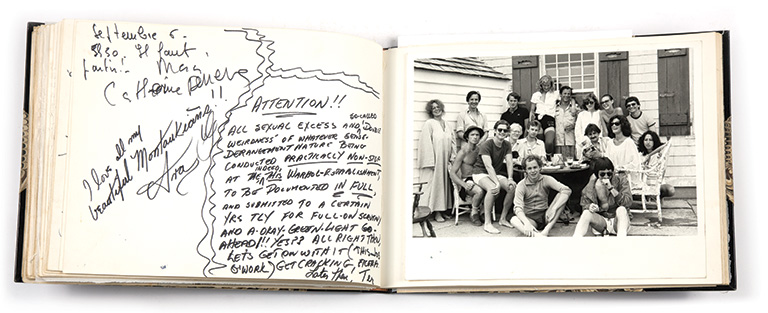

A spread from Warhol’s scrapbook, which he kept at his Montauk vacation home, inscribed by guests, including Catherine Deneuve, 1972–78.

“Since Warhol didn’t write a lot down, there’s a great deal that we don’t know about him,” Wrbican says. “Even his published diaries only cover the last 10 years of his life. The Time Capsules are windows into who he was, what he was doing, where he was going, and who he knew.”

The window that is Time Capsule 79 is the focus of the “B is for Box” chapter of Wrbican’s book. Number 79 holds objects dated from 1941 to 1972, with the majority from 1964 to 1966, an especially prolific period in the Pop artist’s career. Included among the many hidden gems: a New York Times envelope containing Warhol’s 1099 tax form for his commissions in 1961, totaling $2,925 (more than $24,000 in today’s money), and photographs by Edward Wallowitch, one of Warhol’s first boyfriends. Wrbican notes that Warhol used Wallowitch’s photos as source material for many of his works, selectively tracing over them and then making blotted-line drawings.

Unpacking Warhol

Many of Warhol’s belongings occupy 8,000 cubic feet within his museum. There are some 500,000-plus objects in all, including art by other artists such as a Marcel Duchamp Rotorelief and a lithograph by Henri Matisse of his daughter-in-law Teeny, who later married Duchamp after divorcing Pierre Matisse; a bronze bust of the seminal ex-pat modernist writer and North Side native Gertrude Stein; canceled checks; unpaid bills; scrapbooks of press accounts documenting Warhol’s life and work; a hockey stick signed by Wayne Gretzky (“A is for Autograph”); day planners; night planners (“N is for Nightlife”); photos of his beloved dachshunds, Archie and Amos (“C is for Canis Major”); invitations; audio tapes; colorful antique radios; and kimonos.

Warhol had a penchant for the novelties of life, as evidenced by his elaborate collection of dental models highlighted by Wrbican in the “T is for Tooth Fairy” chapter of his book. Warhol’s wide range of wigs, cowboy boots, and colorful corsets are on glorious display in the “F is for Fashion” chapter. (After he was shot in the abdomen in 1968 and nearly died, the artist began to wear corsets to help support his internal organs.)

“Warhol was always interested in the peculiar,” says Warhol biographer Blake Gopnik. “He liked the eccentric, he valued those things.”

A Richard Nixon hand puppet.

And those things, Gopnik points out, are central to modern art. For Warhol, it was all fair game as potential source material. “Warhol’s art and life are so intermeshed,” Printz says, “and the Archive reflects that. Warhol saved everything because everything mattered to him.”

Perhaps that reluctance to let go was formed in his childhood. A working-class, immigrant family, the Warholas raised three sons who came of age during the Depression.

“He loved things, they had a lot of meaning for him,” Wrbican says. “Maybe it was because he didn’t have a lot of things as a child, so every little thing that came into his house would have been precious. I think maybe that stuck with him.”

“The thing about the Archive is that you go in there thinking you’re going to figure out Andy Warhol and what you figure out is that he’s more confusing than you could ever imagine.”

– Warhol biographer Blake Gopnik

He was an equal-opportunity saver, for sure. Warhol didn’t discriminate between the banal and the beautiful.

“Let’s not forget,” Gopnik adds, “he also bought absolutely fabulous Navajo carpets and very interesting art, most especially important works of radical, avant-garde conceptual art.”

The Rolling Stones promotional toy teeth, ca. 1977.

And so, the Archive can be both enlightening and confounding, generally prompting more questions than it answers. It’s a place researchers enter at their own peril. “The thing about the Archive,” Gopnik asserts, “is that you go in there thinking you’re going to figure out Andy Warhol and what you figure out is that he’s more confusing than you could ever imagine.”

Wrbican agrees. “I know a lot about Andy, but I would never say I know everything. I don’t know anyone who could say that. Andy was such a complex person.”

Since there are 26 letters in the alphabet, A is for Archive has a beginning and end; but as Gopnik suggests, it could go on and on.

“It could be 20 times longer,” he says of the book, “and you still wouldn’t be at the end of Andy Warhol or the end of Matt Wrbican’s knowledge of Andy Warhol.”

“I know a lot about Andy, but I would never say I know everything. I don’t know anyone who could say that. Andy was such a complex person.”

– Matt Wrbican

Providing both a look back and a vision for the future, Franzen-Sheehan hopes the publication will lay the groundwork for the next generation of scholars. “It’s such an affirmation of Matt’s work and contributions to the field,” she says, “and it’s exciting to think it could inspire new research.”

Gopnik also imagines Warhol’s delight at the chaos he has unleashed. “In keeping so many objects and so much ephemera,” Gopnik says, “I think Andy wanted to present a situation for future historians that would be difficult rather than easy.”

For Wrbican, it’s personal. “It’s been wonderful working on the book. It’s given me a chance to look back on what I did and start to recognize the work as a real achievement.

“I hoped I would be able to keep this job for life, and in a sense, I have. I think about Andy every day.”

A is for Archive: Warhol’s World from A to Z was a labor of love for many Warhol staff members and supporters, including The Juliet Lea Hillman Simonds Foundation and Barron Family Foundation.

Receive more stories in your email

Sign up