Matt Lamanna, a paleontologist and dinosaur researcher at Carnegie Museum of Natural History, usually begins his Dippy origin story like this.

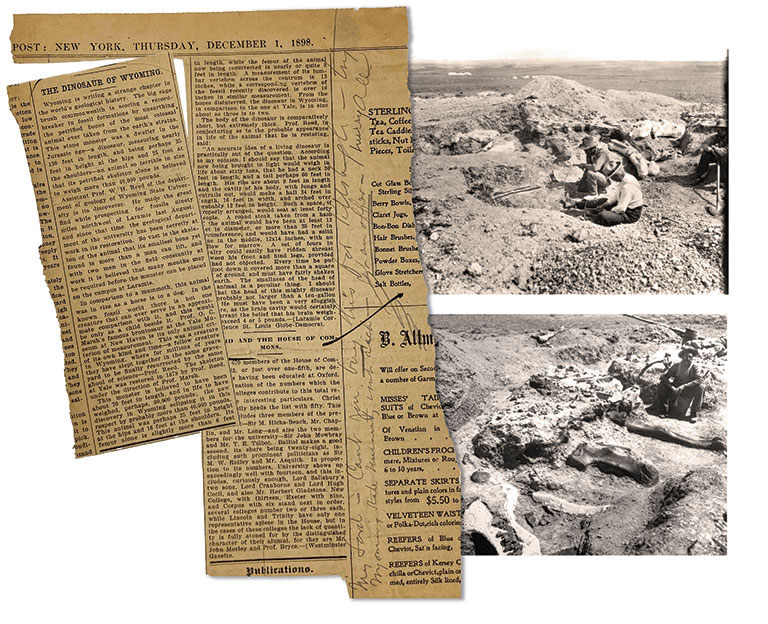

“In late 1898, Andrew Carnegie was reading a newspaper, and he saw an article about a giant dinosaur having just been discovered in Wyoming,” says Lamanna. “And he got really excited because he had just founded what would become Carnegie Museum of Natural History in 1895, and he was looking for a showstopper.”

Whole books have been written about what happened after Carnegie read that newspaper, but the abridged version is that he decided to use his vast resources to excavate the beast behind the headlines. Almost immediately, the expedition he financed ran into a problem.

“Pretty soon it became clear that the only preserved piece of the newspaper dino was a single chunk of thigh bone about the size of a beer keg,” says Lamanna.

One partial thigh bone does not a showstopper make.

“Can you imagine,” ponders Lamanna, “those guys triumphantly returning to Pittsburgh to tell one of the richest men in the world, ‘Hey, we spent all that money you gave us, and brought you back a chunk of thigh’?”

Fortunately, one of Carnegie’s hired fossil hunters, Bill Reed, knew his stuff and ultimately guided the expedition to another place in southeastern Wyoming known as Sheep Creek. In early July 1899, the crew stumbled upon a massive, nearly complete sauropod (long-necked, plant-eating dinosaur) skeleton.

“Around 150 million years ago, sauropods lived on every continent except possibly Antarctica. They ranged in weight from that of a horse all the way up to a sperm whale,” says Lamanna. “They were the largest plant-eating animals in a lot of the environments that they existed in.

“In other words, [the team] had effectively found exactly what Andrew Carnegie was looking for.”

The crew then spent the rest of the summer carefully extracting sauropod fossils and sending them back to Pittsburgh, where more experts busily cleaned rock off the bones and prepared them for display. What’s even better is that the following summer, another Carnegie expedition returned to the same site and turned up yet another sauropod right next to the first.

This was huge for two reasons.

First, it allowed the scientists to compare the overlapping bones of the two skeletons and determine that they were mostly identical, which means the specimens belonged to the same, as-of-yet-undiscovered species. Second, having two partial skeletons allowed them to create a single composite mount that was nearly 100 percent complete—something that is basically unheard of for an animal roughly the size of three African elephants put together.

In 1901, the museum’s paleontologist, John Bell Hatcher, made everything official by publishing a monograph that denoted the first skeleton as the “holotype”—or the specimen used to describe a species for the first time. In the same study, it got its official name.

“And so Diplodocus carnegii came into being,” says Lamanna.

For most fossils, this would be the end of the story. But for Diplodocus carnegii, the adventures were just beginning.

The King and D. Carnegii

In October 1902, Andrew Carnegie was spending some time at Skibo Castle in northern Scotland, which he had recently purchased and fully renovated.

“And then one of these really weird coincidences happens,” says Ilja Nieuwland, author of American Dinosaur Abroad: A Cultural History of Carnegie’s Plaster Diplodocus. “Totally unannounced, the English king, Edward, shows up on Andrew Carnegie’s doorstep.”

Edward’s mother, Queen Victoria, had just died in 1901. And as the new guardian of the realm, King Edward VII set his sights on restoring the royal palaces, which the late queen had allowed to fall into disrepair. “Basically, what Edward wanted was to have a look at Carnegie’s plumbing,” says Nieuwland.

Photo: Graeme Smith

Photo: Graeme SmithBecause Carnegie had just renovated his own castle with all the latest trimmings—electricity, sewers, and indoor plumbing—the king apparently wanted to get some inspiration for his own abodes. Of course, kings aren’t big on advance notice.

In fact, the visit happened so hastily that in order to play “God Save The King” as the monarch approached—as was customary—Carnegie’s servants had to first haul the organ player out of the middle of his bath, says Nieuwland, who is also a researcher at the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences.

And so it was that Andrew Carnegie was giving King Edward VII a tour of his castle when the latter spied a drawing of a curious-looking skeleton hanging on the wall of the cigar room. Carnegie proceeded to tell the story of his prized namesake, Diplodocus.

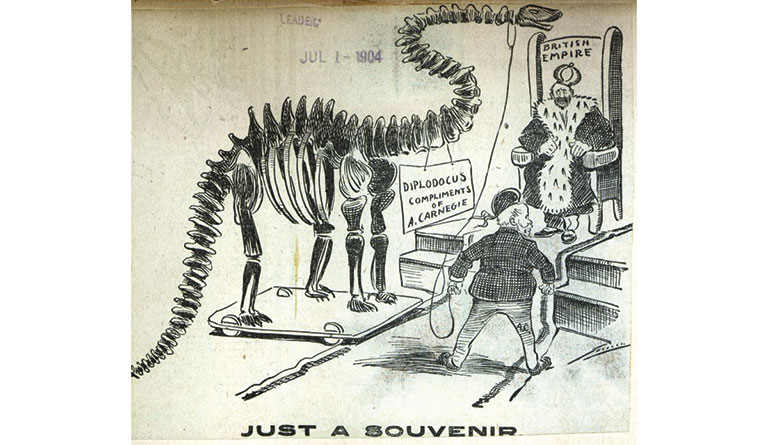

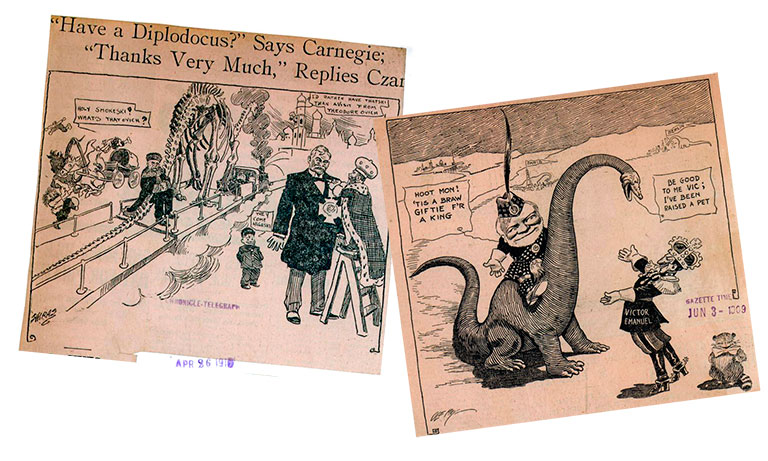

“And the king offhandedly said, ‘Oh, yeah, I’d like to have one of those in London, as well,’” says Nieuwland. “And Carnegie then took it upon himself to make sure that he actually did get that dinosaur for King Edward. Because Carnegie was really keen on establishing himself the equal to all these kings and queens and so forth.

“So Carnegie asked William Holland, who was the director of Carnegie Museum of Natural History at the time, whether they could find another dinosaur,” says Nieuwland. “And Holland answered with something akin to, ‘Are you serious?!’”

Not wanting to disappoint his boss, Holland came up with an alternative idea: Why not create a copy of the one they already had?

“As luck would have it, Carnegie Museums was also an art museum, so they employed a lot of Italian plasterers to make copies of statues and columns and that sort of thing,” says Nieuwland.

While the two dinosaurs had been excavated and shipped to Pittsburgh, they had not yet been assembled into one. For starters, the now-historic “Carnegie Institute” building, which opened in 1895 and housed Carnegie’s library as well as the beginnings of his art and natural history museums, was too small to house a dinosaur so large. Not to mention, says Nieuwland, “handling the original fossil required much more care than dealing with a plaster copy, and therefore progress was slower.”

Preparators first assembled that first replica, or cast, of Diplodocus carnegii at the Western Pennsylvania Exposition Society near Pittsburgh’s Point in 1904. This marked the first time a version of D. carnegii would ever go on display.

By 1905, that cast was shipped to England in 36 crates, where it was set up in what is now known as the Natural History Museum in London. And the crowds went wild for it.

“There are photos from the unveiling where there are people shoulder-to-shoulder,” says Lamanna.

Back in Pittsburgh, big things were in the works.

“Multiple sources cite the discovery of Diplodocus carnegii and Carnegie’s desire to display its mounted skeleton as a major driving force behind the construction of an expanded Carnegie Institute building,” says Lamanna.

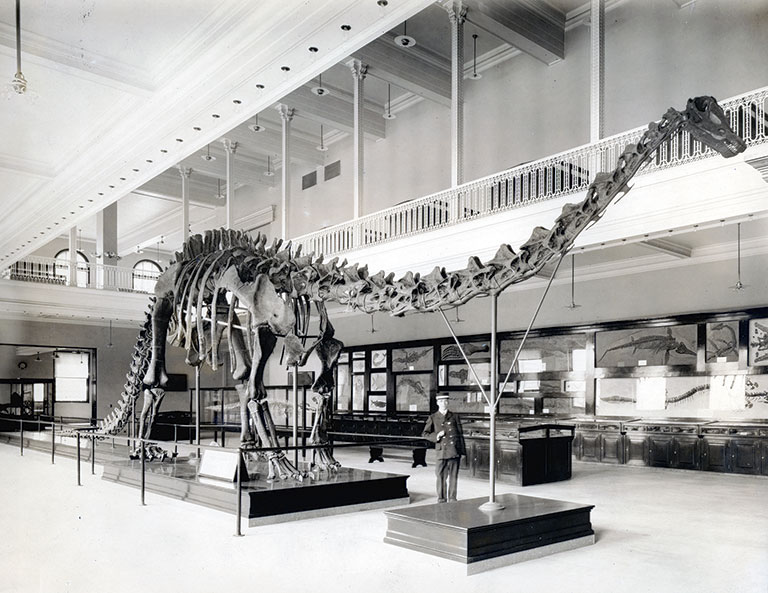

In 1907, the greatly expanded building debuted with its Halls of Architecture and Sculpture, a spectacular foyer for Carnegie Music Hall, and a section dedicated entirely to fossils known as Dinosaur Hall. Diplodocus carnegii finally had a forever home.

“It was a big deal,” says Tom Rea, author of Bone Wars: The Excavation and Celebrity of Andrew Carnegie’s Dinosaur.

The display of real fossils—not just casts—is what made it momentous, explains Rea.

Before long, word of Carnegie’s Diplodocus spread like wildfire. And everybody wanted a piece.

Dippy’s World Tour

At the turn of the 20th century, the largest and most respected museums in the world were only just beginning to catch dino-fever.

“It’s a really amazing time in science when you think about it,” says Rea.

“These were all temples of science,” adds Rea, who is also editor and founder of WyoHistory.org, a project of the Wyoming Historical Society. “These big halls, with high ceilings and dramatic arches, and daylight coming down through the clerestory, and all that stuff that makes these spaces so fun.”

“This is probably the most-seen dinosaur specimen in the history of the planet.”

-Matt Lamanna, paleontologist and dinosaur researcher at Carnegie Museum of Natural History

But most of them had nothing like a Diplodocus. So when requests started to pour in from abroad, Carnegie again seized the moment.

Before long, casts would be sent to some of the largest cities in the world. According to Rea, Berlin erected its Diplodocus cast in March 1908. Paris followed suit that June. The following year, Vienna and Bologna joined the trend, and then St. Petersburg in 1910, La Plata, Argentina, in 1912, Madrid in 1913, and Mexico City in 1930.

For the vast majority of museumgoers of the day, it would be the first dinosaur they’d ever laid eyes upon.

“The cool thing about that is, most of these casts are still on display,” says Lamanna.

“When you think about all the hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of people that see Diplodocus carnegii casts every year in all these European cities, in Latin [and South] America, and couple that with the fact that these mounts have been on display in many cases for more than a century,” says Lamanna, “this is probably the most-seen dinosaur specimen in the history of the planet.”

The House That Dippy Built

No one is quite sure who first coined “Dippy” as the nickname for Carnegie’s Diplodocus.

“I can tell you that the fossil preparator Arthur Coggeshall used the nickname in three articles he wrote in Carnegie magazine about the discovery and fame of D. carnegii in September, October, and November 1951,” says Rea.

Coggeshall had been connected to the museum for more than half a century at that point. In fact, he was on the original expedition in Wyoming when Dippy was discovered.

Nieuwland adds that Coggeshall’s boss, Holland, referred to the Diplodocus as “Old Dip,” but not Dippy.

The one thing we do know is that pretty much as soon as the casts of Carnegie’s Diplodocus started stomping around the world, some scientists took issue with how the mount stood. This was due, in part, to a notion of the day that dinosaurs would have stood like modern-day lizards and crocodiles—low to the ground, with tail in tow and legs sprawled widely apart.

But Holland, who started his career as a butterfly expert before doubling as the museum’s paleontologist, contended in 1910 that the legs of Diplodocus held the animal higher off the ground, more like a mammal.

“Ultimately, Holland’s argument was proven correct,” says Lamanna, who cites the subsequent discovery of fossilized sauropod trackways showing that the feet were placed close together as the deciding factor. “And now everyone that knows or cares at all about sauropods reconstructs them with their legs underneath their bodies, like an elephant.”

More changes came over time—and some of them quite recently. Lamanna arrived at the museum in 2004 and at the time, the tail of Diplodocus carnegii still lay upon the ground. Worse still, it nearly touched the feet of a T. rex, a dinosaur that humans are closer to in time than Diplodocus would have been.

“So this was wrong on two levels,” says Lamanna. “First of all, the dinosaur’s tail probably didn’t touch the ground very much, if at all. And secondly, having the tail lap against the ankles of a 66-million-year-old dinosaur … I mean, you might as well have had a caveman riding the T. rex.”

Getting Dippy’s tail off the ground—and away from T. rex—was just one of many changes that went into the creation of the museum’s Dinosaurs in Their Time exhibition, which opened in 2008 in a space triple the size of the original Dinosaur Hall. Among other changes, Lamanna and his colleagues also switched the bones in Dippy’s forelimbs and added vertebrae in its tail, in keeping with the latest research.

Photo: Joshua Franzos

Photo: Joshua FranzosElsewhere in the exhibition, scientists, artists, and fossil preparators transformed formerly two-dimensional fossils into three-dimensional works of art, including Dryosaurus elderae, Camptosaurus aphanoecetes, and Corythosaurus casuarius. Similarly, real fossil heads of Edmontosaurus regalis and Triceratops prorsus received cast bodies, bringing them to life.

And it’s not just the mounts, says Lamanna. The team has also worked to surround the dinos with plants, rocks, smaller animals, and other facets of the ecosystems they would have once inhabited to create a more immersive visitor experience.

Of the roughly 230 objects now on display in Dinosaurs in Their Time, about 75 percent are real fossils, not casts, making this one of the most impressive paleontological exhibitions on Earth.

Dippy: Teacher And Celebrity

Of course, in paleontology, there will always be questions we can’t answer. For instance, scientists have yet to find a Diplodocus carnegii head, meaning the one sported by Dippy currently is a cast of a skull of the related species Diplodocus longus. And remember, Dippy is already a composite skeleton—meaning it’s made up of multiple specimens.

Lamanna—who has helped discover and name much larger sauropods known as titanosaurs—says that Dippy was the bedrock on which so much future paleontology would be built.

“Diplodocus is one of our first windows into sauropod biology,” he explains. “The appearance, behavior, lifestyle, evolutionary relationships; when we do research on sauropods today, in a lot of ways we’re standing on the shoulders of the people that did research on Diplodocus back in the day, and also Diplodocus itself.”

The museum has also fully embraced Dippy’s celebrity—placing the dino in its logo and stationing a full-bodied gelcoat and fiberglass replica outside on Forbes Avenue. These days, the outdoor Dippy may be the one that gets the most attention, on account of its ever-changing accessories.

“When it’s football season, it might be wearing a Steelers-colored scarf. And just this week, we put up a scarf to recognize the International Transgender Day of Visibility,” says Gretchen Baker, Daniel G. and Carole L. Kamin Director of Carnegie Museum of Natural History. “It gives us a way to celebrate different holidays or express different kinds of community support, or support for our staff who might identify with those communities.”

“Dippy has always been here, since 1907, and represents, really, the beginning of the museum in a lot of ways.”

–Gretchen Baker, Daniel G. and Carole L. Kamin Director of Carnegie Museum of Natural History

Internationally, Dippy the Diplodocus was so beloved that it appeared in The Adventures of Tintin comic, films such as Paddington and Night at the Museum: Secret of the Tomb, and, according to Lamanna, there’s even a good case to be made that

its vertebrae inspired the gigantic sand-monster skeleton seen in the background of the first Star Wars film, A New Hope.

The United Kingdom so cherished its cast that it disassembled Dippy and stored it in the basement to protect it from bombing during World War II. And when the decision was ultimately made to replace the dinosaur in the Natural History Museum’s main hall with a blue whale skeleton in 2017, the cast went on a two-year tour of the British Isles that “smashed visitor records” and raised millions of dollars for local communities due to what they called the “Dippy effect.”

“Dippy has always been here, since 1907, and represents, really, the beginning of the museum in a lot of ways,” says Baker. “It was acquired at a time when there was this kind of mad rush to collect dinosaurs and understand this incredible time in Earth’s history. And we finally had some of the science to do that.”

Diplodocus carnegii is a symbol of “scientific discovery and scientific goodwill,” adds Baker.

Dippy has meant so much to so many. And the chain of events that had to unfold for that legacy to form is nothing short of extraordinary.

Might another institution have found Dippy if Carnegie’s crew hadn’t? Perhaps, says Lamanna, but …

“It seems very doubtful to me that any other institution would have then molded the entire composite skeleton and distributed the resulting replicas to 10 or so prominent museums throughout Europe and Latin America,” he says. “For one thing, that required financial support that very few, if any, other institutions had at the time, or even today.”

Not to mention Carnegie’s chance meeting with the king of England.

“I highly doubt that many other natural history museum founders were hosting powerful monarchs at their personal residences in 1902,” Lamanna says.

Support the museum’s paleontology research with a gift.