Shortly after Dan Leers joined Carnegie Museum of Art in 2015 as curator of photography, the museum acquired Gordon Parks’ critically acclaimed photograph Emerging Man, Harlem, NY.

While researching the photo and learning more about Parks’ practice, Leers stumbled across a March 1944 picture of a worker cleaning a grease drum with lye solution—in Pittsburgh?

“I thought it was a really striking image and I didn’t know that Parks had worked in Pittsburgh,” Leers says. “We dug a little deeper and were surprised by what we found.”

Gordon Parks, Emerging Man, Harlem, NY, 1952, Carnegie Museum of Art, Purchase, The William T. Hillman Fund for Photography, Courtesy of and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation

A call to The Gordon Parks Foundation in Pleasantville, New York, spurred a research expedition through archives that yielded hundreds of photos Parks shot on two separate trips to Standard Oil Company’s Penola, Inc. grease plant in Pittsburgh. This little-known segment of Parks’ varied and storied career chronicles an important chapter in Pittsburgh and U.S. history, detailing the opportunities and struggles of war-era factory workers and the economic, environmental, and societal impact of industry on different communities.

Big industry built Pittsburgh, but it also left many communities on the margins with fewer resources and subject to the ills created by industry, Leers notes.

“We’re still living with the legacy of industry—with the social and racial class divides it created and the ecological impact it continues to have,” he says.

Nearly 50 photographs are now on display in an exhibition curated by Leers, Gordon Parks in Pittsburgh, 1944/1946.

A Humanistic Eye

Scrappy and self-taught, Parks built his portfolio exploring and photographing poverty-stricken areas on Chicago’s South Side.

“I suffered first as a child from discrimination, poverty. … So, I think it was a natural follow from that that I should use my camera to speak for people who are unable to speak for themselves,” Parks said of his developing style.

This early work earned him a fellowship from the Julius Rosenwald Fund in 1942 and distinction as its first Black recipient. It was a big break, paving his way for a job with Roy Stryker, the famed director of the U.S. Farm Security Administration’s (FSA’s) effort to record American life during the Great Depression. Parks’ work with Stryker in the FSA and, later, the Office of War Information (OWI) gave him valuable experience in documentary-style photography.

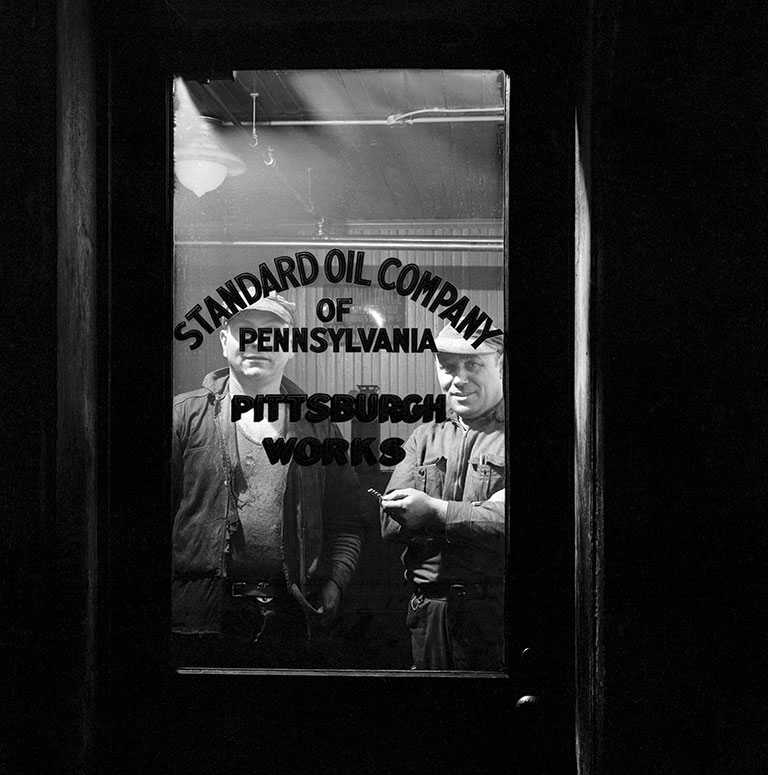

Parks first came to Pittsburgh in 1944, at age 31, on assignment for the Standard Oil Company of New Jersey. Having been accused on the eve of World War II (but later cleared) of sharing trade secrets with Nazis to gain the upper hand in the oil industry, the company was embarking on an epic public relations campaign to clean up its image.

Standard Oil engaged Stryker to coordinate photography for the campaign, creating the largest non-government photo library in America. Parks joined the crew of photo-journalists Stryker hired to humanize the company and document its contributions to the war effort. He was assigned the Penola, Inc. grease plant along the Allegheny River in what is now the city’s Strip District. Under harsh and filthy conditions, workers churned out millions of pounds of “Eisenhower grease,” an essential lubricant for keeping the U.S. military’s tanks, trucks, and jeeps running in wet weather and extreme temperatures.

“He had a humanistic eye. He knew the story of the work was best told through the faces of the workers and by revealing the identities of these individuals.”

-Dan Leers, curator of photography, Carnegie Museum of Art

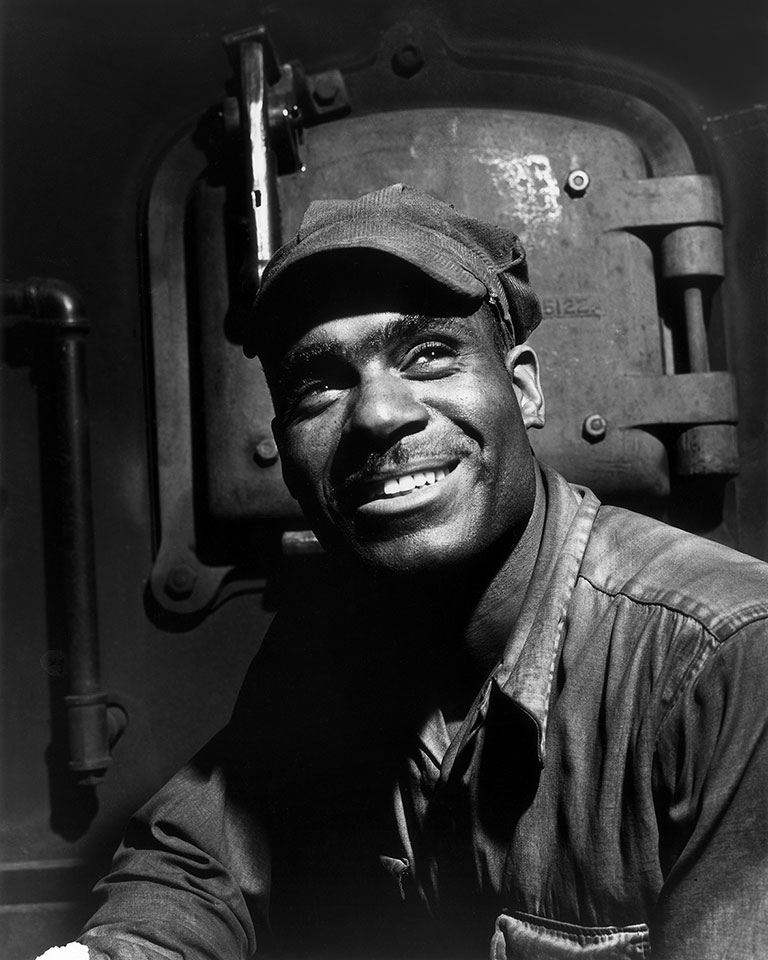

Gordon Parks, Portrait of a grease maker, March 1944, Courtesy of and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation

Parks captured smoggy, industrial Pittsburgh through atmospheric shots of smokestacks and train tracks. He detailed every manufacturing step, from raw material deliveries to finished products packaged for shipping, but always with the human subject in sharp focus.

“He had a humanistic eye,” Leers says. “He knew the story of the work was best told through the faces of the workers and by revealing the identities of these individuals.”

“This exhibition is a tribute to Gordon Parks’ mastery,” Leers says. “In a hot, sticky, dangerous work environment most photographers probably would have done their best to escape as quickly as possible, Parks took time and was dedicated to getting the best possible pictures.”

“I Want To Work For My People.”

Parks knew what it was to be a laborer and had a unique desire and ability to tell the stories of hardworking Americans.

The youngest of 15 children growing up in poverty in eastern Kansas, Parks worked a variety of jobs that offered little opportunity for advancement but exposed him to all types of people. He bussed tables, was a waiter on a train, and played piano in a big band jazz ensemble while he taught himself how to use the camera he bought at a pawn shop.

“I saw that the camera could be a weapon against poverty, against racism, against all sorts of social wrongs. I knew at that point I had to have a camera,” Parks said.

“His professional demeanor, eastern Kansas drawl, storytelling prowess, and ability to put people at ease before his camera allowed him to render a sweeping visual portrait of the urban, rural, and industrial communities,” says Philip Brookman, consulting curator in the department of photographs at the National Gallery of Art, in a guest essay in the catalog accompanying the Gordon Parks in Pittsburgh, 1944/1946 exhibition.

Prior to his first stint at Penola, Inc., Parks worked for the OWI embedded with a squadron of Tuskegee Airmen training to deploy to Europe. He was slated to fly with them and record their efforts on the Italian front, but last-minute protests from Southern lawmakers about a Black platoon receiving so much attention resulted in Parks being grounded.

During his work for Standard Oil, Parks corresponded with literary editor and future civil rights activist Marshall Bragdon, telling him, “I want to work for my people.” Pittsburgh provided a new avenue for Parks to highlight the impact of the Black community on the U.S. military’s success.

Gordon Parks, Charging a kettle where lime-based greases are made. Left to right: Samson Davis, Ernest Matthews, Thomas J. Moran, March 1944, Courtesy of and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation

Gordon Parks, Grease makers and kettle tenders ascending by a freight lift to their working stations, September 1946, Courtesy of and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation

While workers of various ethnicities mingled at the Penola, Inc. plant, Parks noticed that the hottest, dirtiest, and most dangerous jobs tended to be held by Black workers. These gritty and greasy tasks presented the most visually appealing fodder for Parks. But, as he told his boss in a letter:

“Most of the personnel within the manufacturing units were Negroes and it was their jobs that presented the most colorful scenes. An attempt was made to minimize my coverage of their activities so that all the nationalities might be integrated into the story.”

Gordon Parks, Entrance to the plant, March 1944, Courtesy of and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation

Parks connected with Black grease cookers through a shared experience of arduous work and was committed to showcasing their contributions to industry, the economy, and our nation’s standing through the Second World War.

At the time, Pittsburgh’s Black population was surging as the Great Migration drew Southern populations northward in search of better job prospects and less discrimination. The city had one of the nation’s most vibrant Black communities and the country’s largest Black newspaper, The Pittsburgh Courier, with 14 regional editions.

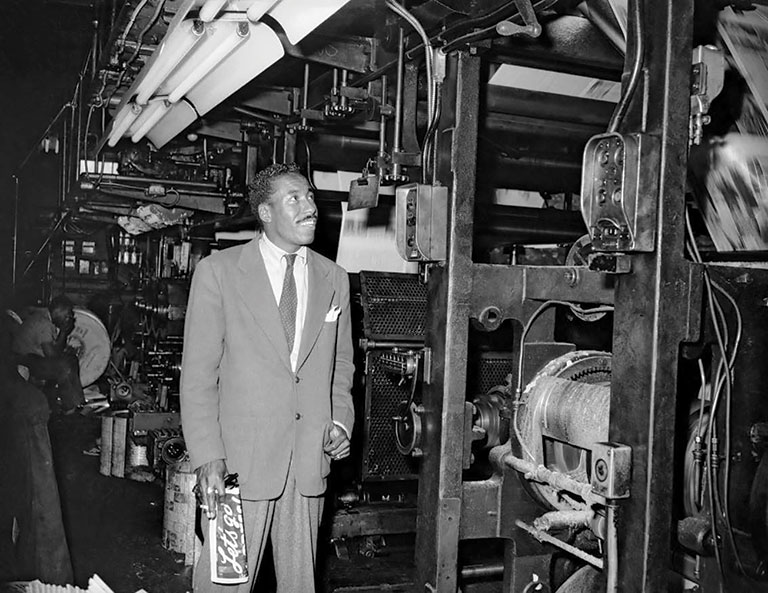

During his 1946 visit, Parks would tour The Pittsburgh Courier office, meeting with its prolific photographer Charles “Teenie” Harris. Both professionals furnished honest depictions of everyday life in Black communities, often documenting lives that were otherwise overlooked, and honoring the work of Black residents who furthered Pittsburgh’s reputation as an industrial powerhouse.

Charles “Teenie” Harris, Gordon Parks in the Pittsburgh Courier newspaper printing plant, September 1946, Charles “Teenie” Harris Archive, Carnegie Museum of Art, Heinz Family Fund

“Both created legacies that continue to resonate with how we understand the world around us,” says Leers, who is intimately familiar with Harris’ work, as Carnegie Museum of Art is home to an archive of more than 70,000 Teenie Harris negatives.

“Teenie Harris’ work had a more place-specific context. He worked in the place he knew, where he grew up, in the place his family was,” Leers says. “Gordon Parks was in the mainstream media, doing work with the same attention and care … on a larger scale, more peripatetically.”

Defining Journalistic Portraiture

Taking the maxim that light exposes truth quite literally, Parks placed the utmost importance on lighting his subjects, often using three, four, or five light sources for a single photograph. He took his time, orchestrating his images, even in the slimy and fiery setting of the grease works.

When Parks photographed two workers underneath a ring of gas jets used to heat oil vats to 450 degrees, a simple click of the shutter would have overexposed the flaming burner and underexposed the workers’ faces. Parks timed his shutter release to expose the flames, closed the shutter without advancing the film, positioned the workers in the frame, and then properly exposed their faces.

Gordon Parks, The huge three story kettles are heated by gas jets that encircle their bottoms. 450 degrees F. is needed to melt some greases, while some melt at 100 degrees, March 1944, Courtesy of and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation

“Parks was very attuned to what the situation needed,” Leers says. “He photographed people within their workplaces, surrounded by the tools of their trade and the results of their labors to give an added layer of understanding of who they were.”

Operating in a distinctive realm between candid shots that capture the subject unaware and formal portraiture, Parks directed and posed his subjects in a way that felt personal and intimate.

“Workers are seen in front of huge stacks of grease blocks—things they literally just finished producing—and you can sense the pride they take in producing them,” Leers notes. “You get the feeling that who was doing the work, and why, was arguably more important than the work itself.”

Gordon Parks, Large squares of grease that have been cooled in pans. Although not extremely hard, the cakes are solid enough to pick up in one piece, March 1944, Courtesy of and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation

Parks wrote books about his photographic technique, coining the term “journalistic portraiture.” Evolving his style as he freelanced for Glamour and Ebony magazines, Parks later became the first Black staff photographer at Life magazine, a post he held for two decades.

In 1968, Life published his photo essay, “Diary of a Harlem Family,” depicting one family’s struggle living in extreme poverty. He believed photos were often the best way to tell a story, but a piece he wrote to accompany the diary spoke powerfully of his wish for people to view his photos with a focus on our shared humanity.

“We are not so far apart as it might seem,” Parks wrote. “There is something about both of us that goes deeper than blood or black and white. It is our common search for a better life, a better world. … There is yet a chance for us to live in peace beneath these restless skies.”

Inspiring Artistic Activism

Journalist and author Mark Whitaker, who explored the heyday of Pittsburgh’s Black community in his book Smoketown: The Untold Story of the Other Great Black Renaissance, speaks to the value of Parks’ Pittsburgh grease plant photos in an essay for the exhibition’s catalog: “Photos are tools to help multiracial generations see a place for themselves in Pittsburgh’s future by understanding their link to its storied past.”

Braddock native LaToya Ruby Frazier won the 2020 Gordon Parks Foundation/Steidl Book Prize for Flint Is Family in Three Acts, her record of the man-made water crisis in Flint, Michigan, told through photographs, texts, and poetry. In her guest essay in the exhibition’s catalog, she asserts that Parks’ work in Pittsburgh represents a subversive act that questioned the status quo by documenting people many would prefer to leave in the shadows.

“Photos are tools to help multiracial generations see a place for themselves in Pittsburgh’s future by understanding their link to its storied past.”

-Mark Whitaker, journalist and author of Smoketown: The Untold Story of the Other Great Black Renaissance

To Frazier, Standard Oil’s 1940s spin campaign has parallels to modern-day efforts by politicians and corporations to distance themselves from social, political, and economic policies that cause damage, particularly to communities of color.

“Had it been left up to politicians, military officers, and businessmen, this vital Black workforce that contributed to the production of 5 million pounds of ‘Eisenhower grease’ during World War II would’ve gone unnoticed and unrecognized and the ways in which racial capitalism was extracted from Black labor in America would remain undocumented,” Frazier says.

“One occupation at a time, one portrait at a time, Gordon Parks went behind enemy lines to refute the snare that inequality and white supremacy set out for us.”

Support for Gordon Parks in Pittsburgh, 1944/1946 is provided by The Pittsburgh Foundation, the Virginia Kaufman Fund, and The Fellows of Carnegie Museum of Art.

Receive more stories in your email

Sign upTags:

Art