Explore all 125 Objects

Walking Man

Since joining Carnegie Museum of Art’s collection as a prize winner in the 1961 Carnegie International, Alberto Giacometti’s bronze Walking Man I has, figuratively speaking, been in constant motion. Standing six feet tall and looking alarmingly thin, his forward-leaning posture suggests he has somewhere to go and must keep moving forward. Although the Swiss-born artist’s practice included paintings and printmaking, it was his iconic series of sculptures that moved him to the forefront of 20th-century art. Nearly 45 years after his death, a Giacometti Walking Man statue—one cast from the same lot as the Carnegie’s—was sold to an anonymous bidder for a staggering $104.3 million.

The Cloud Factory

In reality, the Bellefield Boiler Plant is not in the business of producing clouds. Its purpose is much more practical. The three-story, Oakland-based facility was built in 1907 to power and heat the expanding Carnegie Museums and Library. Originally fueled by coal, the plant now runs exclusively on natural gas and is owned and operated by a consortium of eight neighboring Oakland institutions, including universities, hospitals, and Carnegie Museums. Nestled in the valley below Schenley Park Bridge, the building itself is easy to miss. However, the white, fluffy clouds billowing from its tall smokestack—the result of hot water vapor coming into contact with colder air—captured the imagination of then-University of Pittsburgh student Michael Chabon. In his 1988 book The Mysteries of Pittsburgh, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author dubbed the plant the Cloud Factory. And, so it remains in the hearts and minds of local residents.

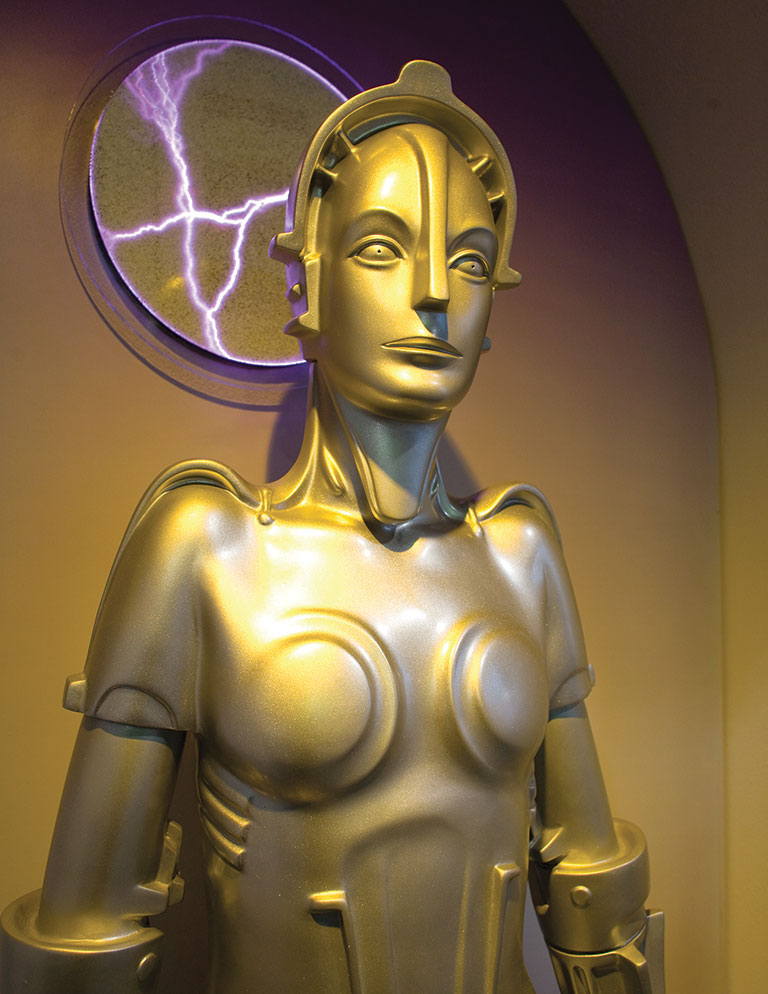

Maria

In Fritz Lang’s 1927 silent German film Metropolis, an industrial magnate bestows upon a tin-plated “man-machine” the face of a real woman named Maria who had stolen the affections of most of the workers in the fictional, turn-of-the-19th-century city. In this futuristic deliberation on the relationship between labor and management, Lang’s Maria looks like a human but lacks any sense of humanity. And, for much of the 20th century, this depiction of robots, however lifelike the rendering, was the norm. In 2009, Carnegie Science Center’s roboworld provided the first physical home for the world’s most famous imagined robots—Carnegie Mellon’s star-studded Robot Hall of Fame. The replicas on display are a tribute to the fictional machines that helped spark the visions of those who created the real robots that followed. Real or not, Maria remains one of the most powerful female images in film history.

Anne in White and Her Blue Silk Sash

Best known for his depictions of the bustling urban landscape and boxing matches in the backrooms of bars in New York City, realist painter George Bellows also made masterful likenesses of his wife, Emma Story, and their two daughters, Anne and Jean. In February 2020, Anne’s daughter, Marianne S. Kearney, donated to Carnegie Museum of Art the blue silk sash her mother wore in the 1920 portrait Anne in White, one of six works by Bellows in the museum’s collection. For the last 14 years of her life, Anne lived in Upper St. Clair and would visit the museum to spend time with the portrait, which was her favorite. “In later years, when she showed me and talked about the blue silk sash, it was easy to see that the sight of it took her to a happy time and place when she had the undivided attention of the father she adored,” wrote Kearney in a letter to the museum. “He gave back to her a portrait of a lanky 9-year-old made beautiful with skilled hands and the eyes of love.” Bellows, who was born and raised in Columbus, Ohio, was regarded by many as one of America’s greatest artists when he died at age 42 from a ruptured appendix.

George W. Bellows, Anne in White, 1920, Carnegie Museum of Art, Patrons Art Fund

Brillo Boxes

In 1964, when Andy Warhol’s Brillo Boxes debuted at the Stable Gallery in New York, collectors and critics were perplexed, and maybe a little annoyed. “Is this art?” they asked. Warhol’s now- famous installation featured 80 plywood boxes, identical in size and shape to the shipping cartons sold in grocery stores, which he and two studio assistants painted and silkscreened with spot-on consumer product logos: Campbell’s Tomato Juice, Kellogg’s Corn Flakes, Brillo Soap Pads, Mott’s Apple Juice, Del Monte Peach Halves, and Heinz Tomato Ketchup. They were virtually indistinguishable from their real-world cardboard counterparts and stacked as if crammed into a grocery store warehouse. The artist envisioned people buying them and walking down Madison Avenue with the boxes under their arms, but they didn’t sell well. The joke, of course, is on the critics: In 2010, a signed Brillo Box sold for $3 million.

Andy Warhol, Brillo Soap Pads Box, 1964, The Andy Warhol Museum; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

Pennsylvania Land Snail

Pennsylvania land snails, which include more than 100 species of both shelled animals and slugs, are found almost everywhere, yet the public knows little about them. They’re important ecologically, providing food for all sorts of mammals, birds, and insects, while they themselves do the critical work of munching on decomposing vegetation. George H. Clapp, a founder of what is now Alcoa and a trustee of Carnegie Museums for more than half a century, collected many things, and shells were a true passion. Shortly after the museum opened, Clapp donated his personal collection of some 300,000 mollusks, with a focus on land snails (including these Mesodon thyroidus from Pennsylvania)—mightily contributing to the foundation of the museum’s collection that now includes nearly 2 million specimens and boasts more land and freshwater snails from the Keystone State than all other U.S. museums combined. Those numbers continue to grow, as curator Tim Pearce and a small band of volunteers work on a definitive census of Pennsylvania’s land snails.

Astronaut Mike Fincke’s T-shirt

Astronaut and Emsworth native Mike Fincke has logged nearly 382 days in orbit during his three space missions. During those flights, he conducted important scientific experiments, performed critical spacewalks, and enthusiastically waved The Terrible Towel in support of his hometown team, the Pittsburgh Steelers. That towel, along with the “I Love Carnegie Science Center, Pittsburgh, Pa.” T-shirt he wore while aboard the International Space Station, has since landed in Carnegie Science Center’s SpacePlace exhibit, which also features the hometown hero’s flight suits, gloves, watches, flip charts, and mission books. As a kid growing up not far from the city, Fincke spent endless hours in the Buhl Planetarium learning—and dreaming—about the stars. Now, he’s hoping to inspire the next generation of explorers to follow their own dreams.

The Neapolitan presepio

It’s an elaborate Italian street scene seemingly captured mid-breath. Carnegie Museum of Art’s Neapolitan presepio shows merchants selling their wares, a marching band in full stride, animals mingling among the residents, both human and heavenly—some seemingly oblivious to the newborn Christ child and his parents. Popularized in the 18th century, presepi were often commissioned by wealthy Neapolitans to celebrate one of the most important holidays in the Catholic faith, situated within present-day Naples. The craftmanship of the day remains impressive some 300 years later, from the textiles used—including silk damask and denim twill—to the tiny props of cheeses molded from clay and fruits and vegetables sculpted in wax. For the past 65 years and counting, the day after Thanksgiving marks the unveiling of this annual exhibition. Following tradition, every year curators rearrange the elements to create the panorama anew. At more than 200 pieces, it’s one of the most complete sets in the world.

The Red Couch

Once a fixture at Andy Warhol’s Silver Factory, the now-legendary red velvet couch first made famous in one of the artist’s underground films was trash turned treasure. It was discovered in early 1964, abandoned on the curb in front of the YMCA located across the street from Warhol’s original studio on East 47th Street. No doubt it was destined to become rubbish until Warhol collaborator Billy Name, the man who literally put the silver in the Silver Factory, recognized its charm and, utilizing its rollers, simply pushed it into an elevator to get it into Warhol’s fourth-floor space. The couch soon became the preferred place for overnight guests to crash, and a favorite focal point for many of Name’s well-known photographs. A few years later, the couch was lost in much the same way it was found: The Silver Factory was on the move to a new location in Union Square, and the red icon was left unattended on the curb, never to be seen again. Nowadays, visitors to The Andy Warhol Museum are greeted by a faithful reproduction in the museum’s entrance space. The couch continues to beckon the famous (Jay-Z is pictured above) and those yet to claim their 15 minutes to take a seat—and a picture.

The Observatory

On select clear nights, visitors to the Henry Buhl, Jr. Planetarium & Observatory at Carnegie Science Center can go to the fifth-floor observation deck, peer through a Meade LX200 Schmidt-Cassegrain telescope, and get an up-close view of amazing celestial wonders. If the stars and planets are aligned, they may even catch a glimpse of Saturn’s rings or the surface of the moon. During the SkyWatch program, amateur stargazers start out the evening with a virtual view of the night sky inside the newly updated Buhl Planetarium. Then they head up to the observatory to try and spy the real deal in the night sky. Science Center staff are on hand to chat about what they see through the high-powered 16-inch telescope that’s provided, or guests are invited to bring their own telescope for an unforgettable night beneath the stars.

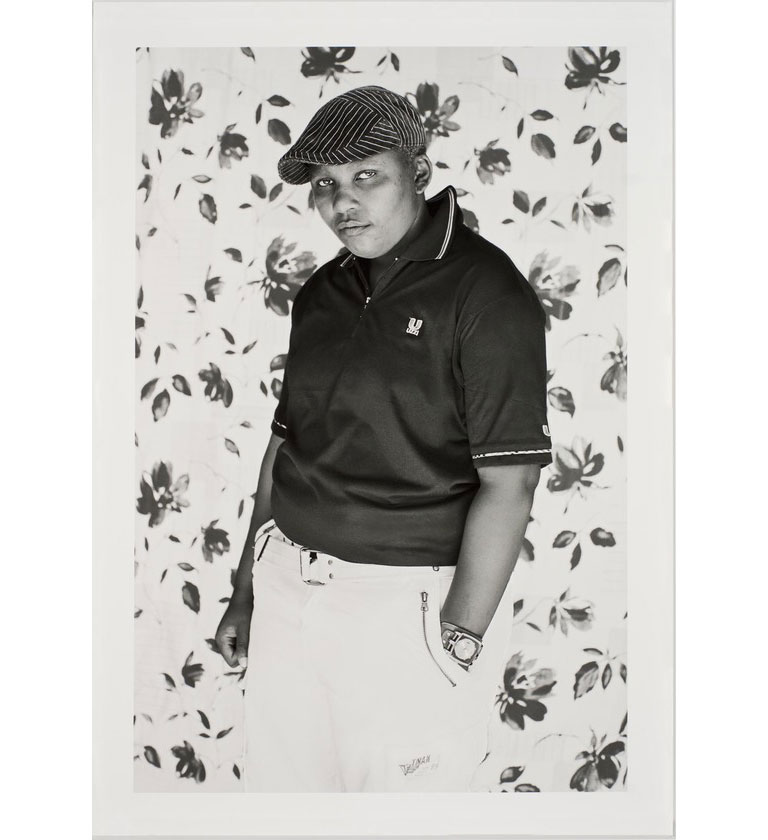

Zimaseka “ZIM” Salusalu, Gugulethu, Cape Town

A self-described visual activist, Zanele Muholi of South Africa has dedicated their career to promoting awareness of their country’s LGBTQI+ communities. Although South Africa legalized same-sex marriage in 2006, discrimination and violence against LGBTQI+ individuals remains widespread. Muholi’s photographs and the accompanying testimonies form a growing record of people risking their lives by living authentically in the face of oppression and persecution. “This is not art; this is life,” says Muholi. “Each and every photograph is someone’s biography.” Portraits from their series Faces and Phases, now numbering more than 300, appeared in the 2013 Carnegie International, including this one, which is part of Carnegie Museum of Art’s collection.

Zanele Muholi, Zimaseka “Zim” Salusalu, Gugulethu, Cape Town, 2011, Carnegie Museum of Art; A. W. Mellon Acquisition Endowment Fund © Zanele Muholi, Courtesy of the artist and Yancey Richardson Gallery

Van de Graaff Generator

Just about every week during the school year, educators for Carnegie Science Center’s Science on the Road program perform science shows for a different elementary and middle school—these days virtually. In a typical year, the program reaches some 170,000 students. In one popular hair-raising lesson, educators pull out all the stops with a machine that makes the same kind of electricity that lightning makes: static electricity. An educator waves a silver wand toward a sputtering Van de Graaff generator, causing a white electric bolt to leap from it with a loud crack, eliciting “oooohs” from the audience. Then, to illustrate how lightning travels, students form a small line—the chain of pain—and link pinky fingers. The staff educator stands on a milk crate so that she isn’t grounded, and as she rests her hand on the generator, her hair stands on end. Laughter erupts. When she touches elbows with the first student in the line, a spark flies, and soon every child in the line pulls away from the surprise of the shock.

Pangolin

Despite their lizard-like appearance, pangolins are mammals that are often referred to as scaly anteaters. They have no teeth and lap up social insects like termites and ants with their sticky tongues—tongues that can grow as long as their bodies minus their tails. Pangolins can be covered in up to 1,000 protective scales—which, like human fingernails, are made of keratin—and their natural defense is to roll up into a ball. But there’s one predator they can’t seem to escape: humans. The weirdly wonderful pangolin is the most illegally trafficked animal in the world—mainly in Asia and in growing numbers in Africa—hunted by poachers for their meat and scales, which are used in traditional medicine practices. This taxidermy pangolin, most recently on view in Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s landmark exhibition We Are Nature: Living in the Anthropocene, is one of 27 in the museum’s care.

Warhol’s Dental Molds

Andy Warhol was a famous pack rat, stashing away direct-mail flyers, greasy wigs, and an assortment of other items he came across in his daily life. But even Warhol experts weren’t sure what to make of all the dental models he kept in his collection of random stuff. All they know is that one summer day in 1982, the artist and his assistant Jay Shriver walked into Columbia Dentoform Corp. on East 21st Street in New York City. They handed over $484 and walked out with an odd assortment of dental forms. Matt Wrbican, the late chief archivist for The Andy Warhol Museum and Warhol scholar extraordinaire, put the 144 objects on display at the North Shore museum in 2004. He said that it was a mystery why Warhol collected the models, some with teeth missing, others with removable teeth or no teeth at all. Wrbican wasn’t sure why Warhol was so fascinated with the curiosities coated in a soft aluminum-pewter sheen, but he speculated that they were related to the artist’s fascination with human anatomy, and his own physical imperfections.

Dental Models, ca. 1982, The Andy Warhol Museum; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

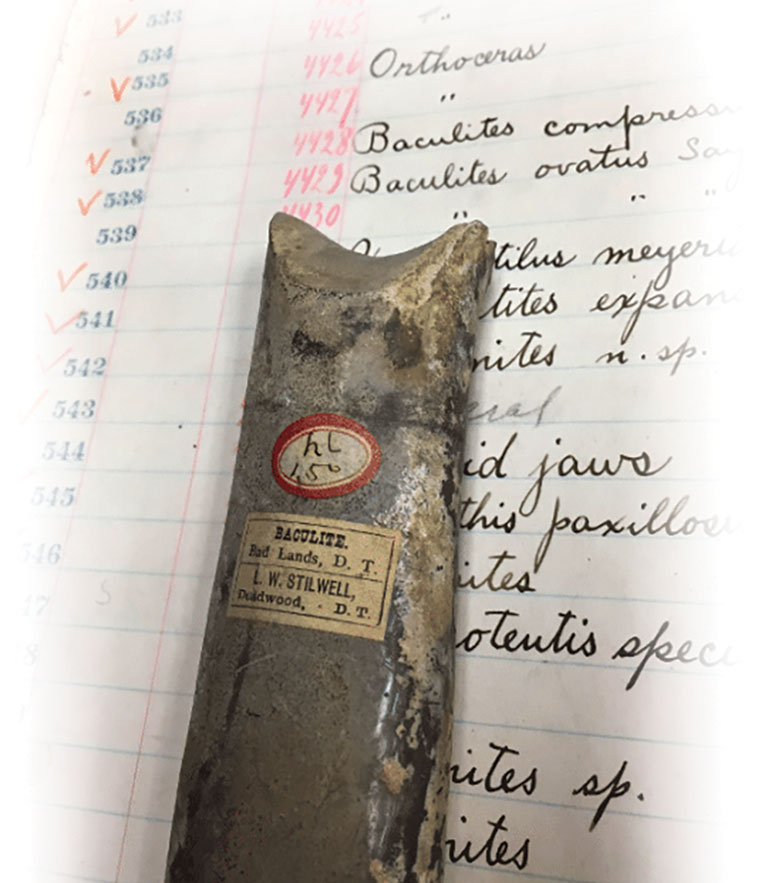

Baculites fossil with L.W. Stilwell label.

The Bayet Collection

Having gained infamy as the place where Wild Bill Hickok met his maker thanks to a gunshot in the back, the Deadwood, Dakota Territory, was not a place for the faint of heart. And yet, that’s where a frail, studious-looking Lucien Stilwell decided to settle in 1879. Looking to outrun a yellow fever outbreak, Stilwell headed west. By 1890, he had established his own thriving business selling fossils and minerals unearthed in the Badlands to world-class collectors like Baron de Bayet of Belgium. By the turn of the century, Bayet had amassed an assortment of 130,000 invertebrate fossils from more than 50 fossil collectors, 15 European countries, and 10 states—a collection sought by museums throughout Europe, Great Britain, and the United States. William Jacob Holland, Carnegie Museum’s second director, told Andrew Carnegie that the acquisition “will make our museum one of the Gibraltar’s of paleontological science in the world,” and it was indeed an early gem of the museum, with specimens exhibited in the dinosaur halls of 1907 and today. In a multiyear project, the museum’s section of invertebrate paleontology is now taking a fresh look at this somewhat hidden treasure.

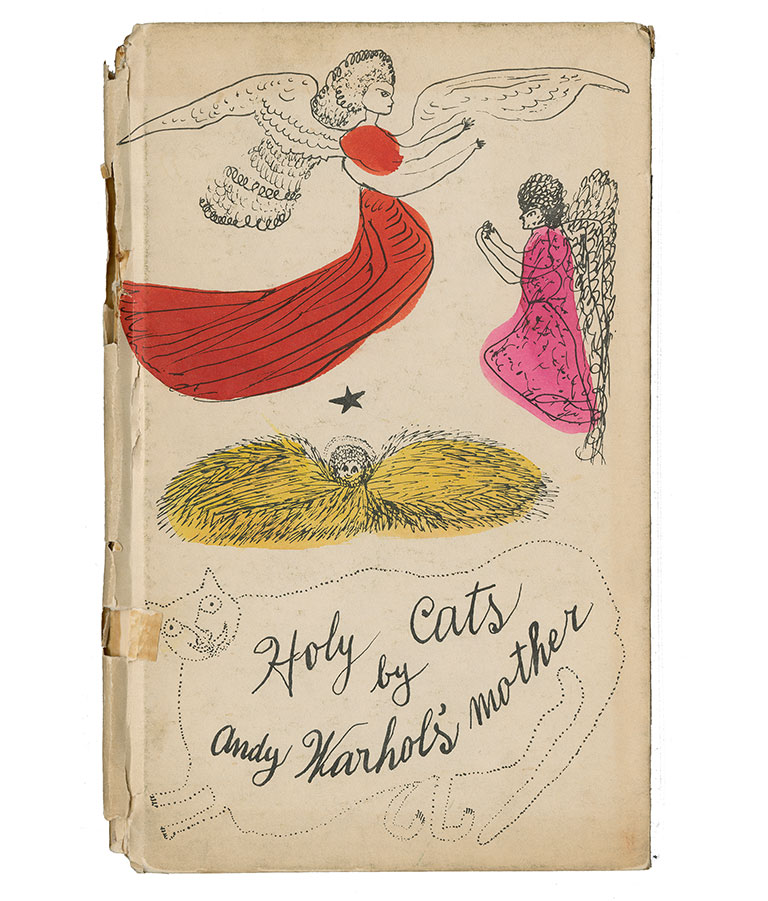

Holy Cats by Andy Warhol’s Mother

Having artistic talent herself, Julia Warhola recognized her youngest son Andy’s abilities from a young age and encouraged him to pursue his passion, including sending him to Saturday art classes at Carnegie Museum of Art. When Warhol moved to New York City in 1949, it wasn’t long before Julia joined him, and he began enlisting her to add her unique handwriting to hundreds of his drawings, advertisements, and book illustrations. Julia also loved to draw, with cats and angels as her favorite subjects. In 1956, the pair made a book about their cats, 25 Cats Name Sam and One Blue Pussy, featuring illustrations combining Andy’s blotted line drawings and calligraphy by Julia. When she left out the “d” in the book’s title, her son loved it and opted to keep it anyway. Four years later, Julia wrote and illustrated Holy Cats by Andy Warhol’s Mother.

Julia Warhola, Holy Cats by Andy Warhol’s Mother, 1960, The Andy Warhol Museum; Gift of Angela Heizmann Gilchrist in Memory of Catharine Stewart Dives

The Art Lending Collection

It was 1991 when artist Alice Patrick’s mural Women Do Get Weary, but They Don’t Give Up first loomed large on the National Council of Negro Women’s Los Angeles building. Some 20 years later, a smaller yet still powerful framed print of the work hung in the Braddock municipal building. Thanks to the Art Lending Collection, Women Do Get Weary is one of more than 160 artworks available to anyone with an Allegheny County library card to borrow, display, and enjoy for up to three weeks at a time—changing the dynamic of who gets to interpret and experience art. Now funded by the Heinz Endowments, the collection was the brainchild of Braddock-based artists Dana Bishop-Root, Leslie Stem, and Ruthie Stringer. Their idea took root as their contribution to the 2013 Carnegie International, with all exhibition artists contributing original artwork for the collection. Since then, it has grown to include donations from private collections, original works from local artists such as fellow Braddock resident Jim Kidd, people imprisoned at the South Fayette Correctional Institution, and framed posters of classics.

Saturday Art Classes

They’ve survived the Great Depression, a world war, the rise and fall of art movements from Cubism to Pop, and now a pandemic. For more than 90 years, Carnegie Museum of Art has continued the tradition of working with Pittsburgh’s young artists to help them hone technical skills and foster imagination at Saturday art classes. While the name of the classes changed through the decades—Tam O’Shanter, Palette, and, currently, The Art Connection—the artistic discovery they’ve awakened in generations of students, often within the same family, has remained the same. For a small number of students—Annie Dillard, Andy Warhol, Jeff Goldblum, and Mel Bochner, to name a few—the program was an early step on the way to international renown. For many others, the classes have been a magical family tradition.

Sol LeWitt’s Wall Drawings

The colorful geometric drawings that grace the staircase leading up to Carnegie Museum of Art’s Scaife Galleries are hand-painted. Just not by the artist himself. A pioneer of conceptual art, Sol LeWitt took a decidedly hands-off approach when it came to putting brush to canvas (or wall). He created art by developing an idea and producing written instructions for other artists, many trained in his studio, to carry out. He believed the input of others was part of the process, and even children have contributed to some of his public works in schools. The museum’s pair of side-by-side wall drawings were originally painted in the mid-1980s—LeWitt designed the second work once he saw the location of the first. Twenty-some years later, their colors faded by the natural light streaming in through the large window to the Sculpture Court, the murals were repainted by museum staff joined by local artists. The project took on new significance when the 78-year-old Le Witt died shortly after the repainting was completed in 2007.

Carnegie Science Award

For 25 years, Carnegie Science Center has recognized the region’s shining stars in science and technology—ingenious students, inspiring educators, and industry-changing entrepreneurs—at its annual Carnegie Science Awards. A panel of past awardees and industry leaders selects winners whose contributions have led to significant economic or societal advancements in western Pennsylvania. With the support of committed sponsors, a new addition for the upcoming 2021 awards is the recognition of champions in sustainability and science, technology, engineering, and math equity.

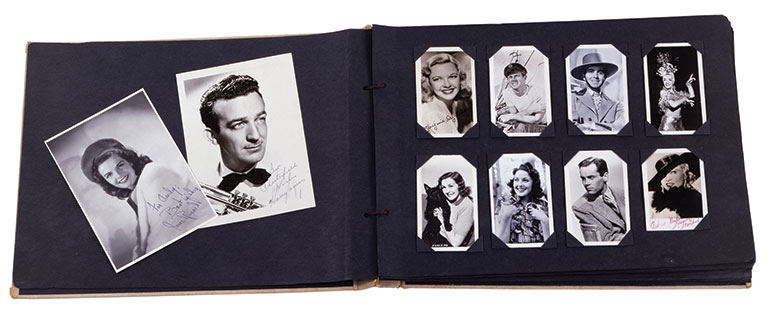

Andy Warhol’s Movie Star Scrapbook

Like a lot of kids growing up during the Great Depression and World War II, Warhola brothers Paul, John, and Andy would find refuge in the three movie theaters near their South Oakland home. Paying a nickel or two, they knew that as soon as the lights dimmed the screen would be illuminated with the celebrities of the day—Joan Crawford, Henry Fonda, Jane Russell, and Mae West among them. Andy was particularly star-struck. He convinced Paul to write letters requesting signed photos, and Andy would meticulously add every new arrival to his rapidly expanding scrapbook. The album filled to more than 30 pages, but the 1941 hand-colored photo signed, with typo included, “To Andrew Worhola, from Shirley Temple” took center stage, until at some point it was removed and later found in Time Capsule 61.

Photograph album (Andy Warhola’s childhood movie star scrapbook), ca. 1938-1941 © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc

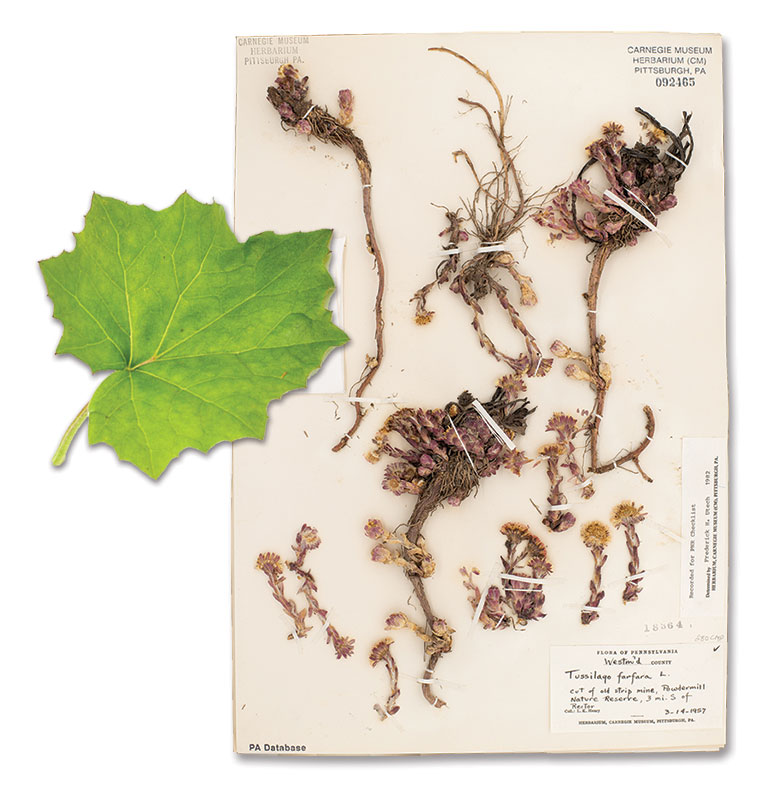

An Early Bloomer

On March 14, 1957, botanist Leroy Henry walked through the woodlands around Powdermill Nature Reserve, just one year after it was established as Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s field station, and collected coltsfoot, known scientifically as Tussilago farfara. To the untrained eye, the plant with yellow flowers might look like a common dandelion. But Henry, a former longtime curator of botany, knew what he had. Native to Europe, North Africa, and Asia, its flowers bloom in early spring, followed by leaves that look like—you guessed it—a colt’s foot, and last well into the summer, making it a good species for research. In fact, the coltsfoot is among the first plants to be used in a pioneering study published in 2006 using herbarium specimens. In Southern Quebec, they found that coltsfoot bloomed 15–31 days earlier in recent decades, compared to pre-1950. Earlier blooming was strongly linked to climate change. It’s one of hundreds of plants highlighted in Collected on This Day, a weekly blog by Curator of Botany Mason Heberling that’s funded by the National Science Foundation and features the important scientific and cultural stories of the specimens in the museum’s herbarium, making clear why natural history collections help us understand the world around us.

Binary Flip Clock

Visitors eating lunch in Carnegie Science Center’s RiverView Café may look up at what appears to be a modern wall sculpture made up of many plates. But wait. Those square plates are moving, flipping one after another, perfectly in sync. The plates, which are keeping the exact time, are the mechanical pieces of the largest binary flip clock ever created. Doug DeHaven, a mechatronics engineer at the North Shore museum, wanted to make a timepiece that was both visually interesting and functional for a new wall erected as part of the addition of the PPG Science Pavilion. But he didn’t want a clattering clock with noise that would disturb staff. So he dreamed up a mechanical creation consisting of three rows representing seconds, minutes, and hours—and, of course, a splash of artistry. Each column includes graphics that represent different ways humans count—from military time to Roman numerals, American Sign Language, and the programming language Scratch.

Mallard Duck Decoys

North American hunters have used decoys for centuries. Indigenous Americans fashioned them from reeds, clay, and stuffed skins to lure migrating birds within range of their arrows and spears. European settlers observed the effectiveness of what were often quite rudimentary decoy rigs, such as duck skins wrapped over floating logs arranged to look like a wading bird and adopted the practice. By the early 19th century, both commercial and sport hunters were using carved wooden decoys. However, some hunters preferred real skin decoys known as “stuffers,” like these made by Whistler Brothers. They were popular during the Depression and donated to Carnegie Museum of Natural History in 1980 by benefactor Edward O’Neil. Made from farm-raised mallards, the skins were wrapped around cork bodies, heavily varnished so that they float, and lead weights were added to the undersides to allow them to float upright. “I always thought this was a cool form of taxidermy begun by Indigenous people and still used to some extent today,” says Stephen Rogers, collection manager for the section of birds and a taxidermist.

Dippy’s Scarves

Diplodocus carnegii, the long-necked star of Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s world-famous collection of Jurassic giants, got its own public sculpture in 1999, celebrating a century since he was unearthed at Sheep Creek, Wyoming. That winter, Janice Heagy, former Carnegie Museums staff member, handmade Dippy a Jurassic-sized red and green scarf to mark the holiday season, kicking off a now-beloved Pittsburgh tradition—dapper Dippy dressed for the occasion: Steelers playoff football, Pitt move-in day, and LGBTQ+ Pride Month, to name a few. Dippy’s accessories have grown in number over the years to the point that he now has his own closet at the museum stuffed with at least 15 oversized scarves, lovingly made by both staff and volunteers. There’s also a top hat and bow tie, a mortarboard, and, most recently, several face masks. And every St. Patrick’s Day, Dippy celebrates the wearing of the green with his longest and most popular adornment measuring 18 feet long!

Receive more stories in your email

Sign up