The four Carnegie Museums are 24-hour operations, so even when the lights go down and the doors close to the public, staff stand watch. But what happens during an unexpected closure that stretches nearly four months and requires staff to physically distance from one another? This previously unimaginable scenario was not (yet) in the emergency planning playbook, so staff had to adapt and work collaboratively to figure out how to best care for the collections and the facilities that store them, all while keeping each other safe.

For the facilities, planning, and operations team, this meant overseeing the around-the-clock safety and security of not just the museums, but also the Bellefield Boiler Plant, which provides steam for hot water and heat to much of the Oakland neighborhood; the 2,200-acre Powdermill Nature Reserve in the Laurel Highlands; and several off-site collection storage facilities—all with dramatically fewer eyes and ears on the ground.

“It doesn’t make for boring days,” says Tony Young, the department’s vice president.

For instance, in May, Carnegie Museums’ Oakland campus experienced a brief power outage that, even though it was only minutes-long, set in motion a flurry of activity that would last hours. On the immediate to-do list: bring all of the facility’s equipment back online, including the boiler plant; check on the well-being of Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s live animal ambassadors; and confirm that the 20 freezers storing perishable specimens and tissue samples are fully functioning.

“We never envisioned closing. We were thinking about the need for deep cleaning on a daily basis. But we thought we’d have to do it for 1,000 people a day, not 15.” – Tony Young, vice president of facilities, planning, and operations

Tony Young, the man in charge on the ground, inside the chiller plant on the Oakland campus. Photo Joshua Franzos

“It’s something we’re totally equipped to handle, it’s just a lot more added responsibility with a lot fewer people in the building,” says Young. He notes that, in order to maintain social distancing and keep on-site staff to a minimum, his team members worked in daily and weekly rotations. “My main goal was making sure everyone follows protocol for whatever issues came up, so if there was a problem we could catch it in a minimal amount of time.”

Safeguarding the specimens and the art

Wearing a mask and wielding a flashlight, Conservator Gretchen Anderson snakes her way through the darkened exhibition halls of Carnegie Museum of Natural History. On this Wednesday during the extended COVID-19 closure, she takes a deliberate path that’s the reverse of the one she took the last time she was in the museum, looking at the same things but from a different vantage point.

“I’m someone who goes into the museum on an occasional evening, so it’s not a completely new experience being in there alone in the dark,” she says, noting that the lights stay off to limit unnecessary light exposure. “But still, it’s kind of creepy.”

Like her collections-care colleagues at Carnegie Museum of Art and The Andy Warhol Museum, Anderson is keeping close watch on the museum’s holdings by monitoring the temperature and relative humidity levels in both the galleries and storage spaces, using handheld devices in partnership with the ongoing monitoring tied to the HVAC systems. She checks pest traps, too, and always has an eye peeled for leaky pipes.

“I hate living on luck, but I feel at times like we have been,” she says, noting the challenges of working in a 125-year-old building. “With the bad rainstorms we’ve had since March, there has thankfully been very little water coming in. But we know what can happen and we’re watching it closely.”

The “we” overseeing the museum’s wondrous collection of millions of objects and scientific specimens currently consists of Anderson and a pair of facilities colleagues who conduct walk-throughs of the gallery and collection spaces three days a week, with security guards charged with checking the galleries in between. Prior to the closure, Anderson visited each of the museum’s scientific sections, including the Alcohol House, accompanied by its collection manager, who would highlight top concerns such as patched ceiling leaks and the operation of specimen-filled freezers. Not so during the COVID-19 closure, which she notes has been a good exercise. Spending more time in areas she doesn’t always frequent has made her more aware of a whole host of minor things she’d like to address when the museum is on the other side of this.

Conservator Gretchen Anderson

Anderson even does sweeps of the museum’s research library and archives—after all, silverfish and cockroaches love paper, she notes. Equally as worrisome as leaks and pests, the conservator says: “Changes in temperature and relative humidity can cause a significant amount of damage. Like a virus, humidity goes where it bloody well pleases.”

With taxidermy, for instance, the skin of an animal is stretched over a rigid body, and the skin expands when moisture increases and contracts if there’s less moisture in the air. “So, basically, it’s like a drumhead and it can crack and tear,” explains Anderson.

Fortunately, she’s encountered no major issues to date. She’s even enjoyed a special moment or two with a Benedum Hall of Geology diorama featuring an underwater scene from Pennsylvania between 286 and 320 million years ago.

“It was like running into an old friend,” she says of the work she previously helped return to its original glory. “It’s not an especially spectacular piece, but I get very involved with the objects I work with. I stopped, used the flashlight to illuminate it, and spent some time just appreciating it.”

Across town at The Warhol, Amber Morgan, director of collections and registration, explains how an extended closure is actually a good thing for the art she manages. “For the type of collection we have, acrylic paintings that have a lot of light-sensitivity issues, the closure actually gives the paintings a chance to take a break.”

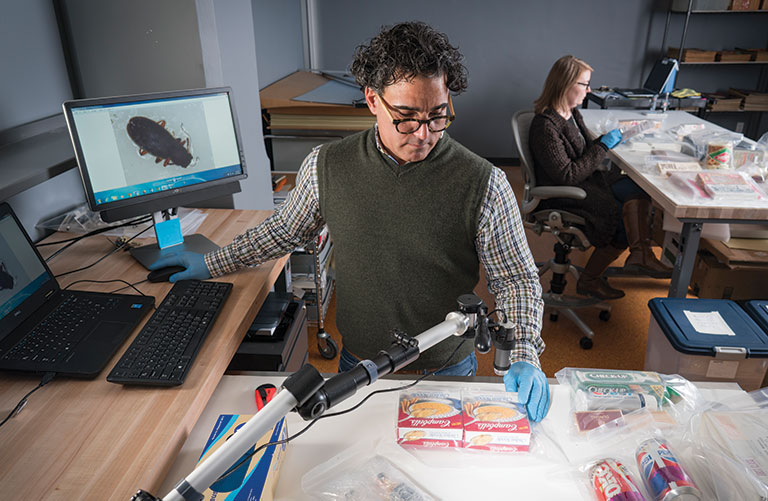

Collections staff members John Jacobs and Amber Morgan (in background) in the conservation lab prior to closure. Photo: Joshua Franzos.

“Conducting the walk-throughs has felt oddly alien, almost like exploring a very familiar space but in a parallel dimension—queue the Twilight Zone theme.” – John Jacobs, collections associate at The Warhol

Her team member, Warhol Collections Associate John Jacobs, had the task of conducting weekly walk-throughs of all museum galleries and art storage spaces, with security serving as the first line of defense in between.

“Conducting the walk-throughs has felt oddly alien,” says Jacobs, “almost like exploring a very familiar space but in a parallel dimension—queue the Twilight Zone theme. Normally The Warhol is such a lively and boisterous place, but during the walk-throughs there’s a tomb-like and frozen-in-time ambiance.”

As a way of documenting the unusual circumstance, on his first post-closure visit, Jacobs recorded his first-ever screen test—a museum interactive modeled after Andy Warhol’s silent, black-and-white film portraits—while wearing the marker of the time: a mask. On subsequent trips, the gravity of the moment seeped in: “My thoughts turned toward contemplating the fickle and capricious set of circumstances that were necessary for man-made objects from ancient civilizations to survive through tumultuous events, making it into our time, and how that sort of intersects with my small role in preserving Warhol’s objects.”

Bonding with the animal ambassadors

For Carla Littleton and the swimming, hopping, and slithering animal ambassadors at Carnegie Science Center, not all that much changed during the museums’ temporary closure, except the days were a bit shorter. Routine is key for the health and well-being of the members of the collection—about 70 species of mostly reptiles, amphibians, and fish, almost all native to Pennsylvania. Something as seemingly incidental as when the lights are turned on and off is important to the animals’ day and night cycles, says Littleton, the animal and habitat coordinator.

She and another part-time staff member fed and cared for the animals, most of whom live on exhibit in the field station of the first-floor H2Oh! exhibition, a river-focused exploration. “One of the first things we hope people learn is that these are animals that you can find in the city, even right here in the middle of downtown, which makes an impact on people,” says Littleton. They educate people of all ages about what it means to be a threatened and endangered species, too. And during the closure, instead of bringing their conservation message to curious in-person visitors, an eastern box turtle, an eastern tiger salamander, and a 5-year-old milk snake became some of the Science Center’s newest social media stars, reaching a wide digital audience. On World Turtle Day, the public tuned in as Littleton helped a pair of northern map turtles get some exercise swimming inside a heated baby pool, and the box turtle roamed free on a long and surprisingly fast walk. “It’s good enrichment for the animals and a lot of fun for our audiences to see what goes on behind the scenes,” she says.

Carla Littleton with an adult female American toad.

At the Museum of Natural History, the animal husbandry team led by certified veterinary technician Leslie Wilson also dipped into their enrichment toolbox as a way to keep the museum’s animal ambassadors happy and healthy during the closure. They include an African pygmy hedgehog; an adorable relative of the raccoon known as a coatimundi; a pair of skunks; and several birds, including a sun conure. Three animal caregivers took shifts to provide “lots of extra love and lots of extra enrichment,” says Wilson, since the animals weren’t in front of human crowds. The most recent enrichment additions: heavy-duty toys made from recycled fire hoses, thanks to the volunteer group Hose2Habitat. The team also served up new and different foods, and made the animals work harder for the payoff, using puzzle boxes to help encourage natural foraging behavior. “It makes these basic tasks more fun for them, mentally and physically,” says Wilson.

And staff aren’t the only ones getting used to face coverings. Wilson and team wear masks when working with the animals for safety but also so the animals get used to their human friends wearing them. “The closure stinks for everyone, but the profound silver lining is it’s allowed us to deepen our relationship with individual animal ambassadors,” says Wilson.

Veterinary technician Leslie Wilson and Mango the sun conure practice for a live animal encounter.

“The closure stinks for everyone, but the profound silver lining is it’s allowed us to deepen our relationship with individual animal ambassadors.” – Leslie Wilson, certified veterinary technician

“We always learn a lot about the animals every day,” says Wilson. “Throughout this process, they’re learning a lot about us, too, and it takes time for them to create new bonds. So, in that way, this one-on-one time has been really productive and personally and professionally satisfying.”

Getting ready for staff and visitors

On March 14, the day Carnegie Museums temporarily closed to help slow the spread of COVID-19, custodial staff, while safely socially distancing, got back to work. At the Oakland museums, they cleaned and sanitized every public and private space inside Carnegie Music Hall before locking them up. In the days that followed, they repeated the process throughout the building.

“We’ve deep cleaned and sanitized every public space and every open space in every office,” says Lysa Bennermon, the assistant facilities manager who knows every nook and cranny of the sprawling Oakland campus, having first worked in security for a combined total of 26 years. “My familiarity with the building is definitely a plus,” she says.

She and her team are responsible for not only the Oakland museums but two off-site storage facilities and the 11 cabins used by researchers at Powdermill Nature Reserve. As limited staff came in and out of the facilities daily, cleaning staff followed their paths, wiping down door handles and elevator buttons, and using a hospital-grade disinfectant misting spray. Keeping the facilities clean for staff and visitors is always critical, but in the midst of a health crisis, the weight of the responsibility was not lost on Bennermon. “I still can’t wrap my mind around it sometimes,” she says. “But we’ll be ready. People will see us out on the floors when they visit.”

Young and team started ordering more cleaning and protective-wear supplies—anti-viral disinfectant, hand sanitizer, and face coverings—at the end of February. “We never envisioned closing,” says Young, who, throughout the management of this crisis, has taken on a leadership role among his peers both regionally and nationally, leaning into his experiences working in a shipyard and at Guantanamo Bay Naval Station in Cuba for 10 months as a reservist in the Navy. “We were thinking about the need for deep cleaning on a daily basis. But we thought we’d have to do it for 1,000 people a day, not 15.”

Tracy Palmer, a custodian at Carnegie Science Center and a grandmother of seven, says she misses the sound of rambunctious kids having fun and learning in the North Shore attraction, but she’s thankful to have dedicated time and focus to prepare for reopening.

“We’ve been very busy,” Palmer says. “We’re detailing the bathrooms, cleaning all of the rugs, sanitizing the exhibits, cleaning out the vents. It’s a good, deep clean, and we’ll have the place smelling good and fresh for visitors.”