The four-inch swatches of fabric—snippets of inspiration from all over Pittsburgh—arrive daily for Tereneh Idia. The envelopes, mailed to a friend’s studio, contain embroidered squares, oval-shaped patterns, even little scraps of cloth that otherwise might have been tossed out. One is from a woman who has been crocheting while in chemo. Another is cut from material a woman used to fashion her late husband’s favorite pajamas. Using this colorful and inspiring mishmash along with remnants from her own stash, Idia is making a three-rivers-themed garment to build a sense of community.

The designer’s communal clothing piece is one answer to the question: How do you create fashion during a pandemic, when the runways are closed and even designers posting to social media are posed in their sweats?

Fashion designer Tereneh Idia invited the public to contribute to a communal garment. Here she surrounds herself with fabric pieces mailed to her from all over Pittsburgh and beyond. Photo: Joshua Franzos

Idia is doing what she has always done—working with others from afar. She founded Idia’Dega fashion line after collaborating with the Olorgesailie Maasai Women Artisans of Kenya and the Beading Wolves of the Oneida Indian Nation of New York.

Logistical problems notwithstanding—there’s scarce internet access in the Kenyan village two hours from Nairobi—she designs long-distance by sending texts or using WhatsApp. She also flies halfway around the world to work collaboratively. The sale of any garment is split three ways, and Idia’s collaborators can earn more by making samples and creating additional designs, inventory, and new products. With intricate beading and indigenous adornment, the elegant clothing and accessory line has been shown during New York Fashion Week and in Paris, Copenhagen, Nairobi, and Pittsburgh.

Idia’s new garment, OAM PGH: A Community Fashion Project, is an ongoing work that she envisions passing on to other Pittsburghers. She notes, “I don’t think it will ever be done.”

The mighty Ohio River is symbolized by the work’s long train, with the city’s other two famous rivers represented by billowing sleeves, the Allegheny on the right, the Monongahela on the left, and the “crown” or head as the Golden Triangle. Unisex and ever-changing, it will have an asymmetrical hemline and beaded embellishments.

Some of the submissions have brought Tereneh Idia to tears. Pictured is a wedding yarmulke a new friend and cancer survivor made as a wedding gift for her nephew and decades-old swatches donated by a woman whose late sister was an inspiring fashion designer and had collected the material.

Some fashion designers create by focusing on their singular vision. But Idia is inspired by her partnership with 37 women whose contributions within their own culture have largely been overlooked.

Her relationship with the Maasai women began with a trip to Kenya in 2013, when Idia moved into a hut without electricity and joined a circle of artisans to observe their work on beaded jewelry. When they agreed to work with her on her business idea, she asked them to sketch their ideas on a piece of paper. They laughed.

“What’s so funny?” she asked through a translator.

Turns out, they had never used a pencil. So Idia asked them to point the pencil tip where they would put a bead. Soon they had filled an entire sketch book, and Idia’Dega was born.

Idia takes a deliberate approach to design, and it doesn’t involve flipping through the pages of Vogue. “Once I start designing, I can’t look at clothes. I can’t look at fashion. I look at architecture or nature. I can’t listen to any music with lyrics. When I’m sketching, I listen to [John] Coltrane or Charlie Parker.”

The North Side resident is one of 19 area makers whose work will be featured in Locally Sourced: Contemporary Pittsburgh Products, an upcoming exhibition at Carnegie Museum of Art highlighting functional goods and home furnishings in clay, glass, metal, fiber, wood, paper, and emergent materials and technologies. Idia’s contribution is her Narok Tomon gown, a collaboration realized in 2014 using hemp silk and glass beads.

The Pittsburgh area is home to many talented makers, says Alyssa Velazquez, curatorial assistant for decorative arts and design at Carnegie Museum of Art and organizer of Locally Sourced. For the exhibition, which will be on view in the museum’s Charity Randall Gallery, she selected artists who excel at combining their studio practice with creative business models.

“In order to be financially successful, most makers can’t just sit in front of a sewing machine or a pottery wheel. They have to be online,” says Velazquez. “They have to make compelling photographs of their work. They have to be present at makers fairs and on social media. The amount of networking is astounding.”

Hand-sewn masks and hope

Nisha Blackwell invites people into her Wilkinsburg showroom to design their own bow ties. Bespoke dandies made of velvet with gold trim on the edges. Blingy beauties with charms in the knots. Elegant creations made of rare upholstery discards. Neckwear that makes the wearers stand out as they walk down the aisle on their wedding day or stride into a sales pitch.

Before COVID-19, Blackwell and her team of seamstresses—three in-studio and 18 based at home—produced up to 500 custom-made bow ties a month.

During the pandemic, self-taught seamstress and Knotzland founder Nisha Blackwell quickly shifted to making masks for essential frontline workers.

In early spring, the loss of business due to the pandemic forced Blackwell to cut hours and limit project promises to most of her workers. Thanks to grant money, she’s hired some back for another massive sewing project—mask making for essential frontline workers in grocery stores, funeral homes, pharmacies, and gas stations. By early June, she and her staff had already made about 5,000 masks as part of (mask)MAKERS PGH, an alliance of local small businesses and nonprofits that Blackwell describes as a solution-driven collective at the intersection of art, manufacturing, technology, creativity, and business. The group has received requests for more than 9,000 face coverings and has been able to provide masks free of charge to community organizations that serve the public.

“I found hope in taking action to piece things back together.” – Nisha Blackwell

Sewing masks, one after the other, has been meditative, says Blackwell. “It gives me something to focus on, the details. You don’t have to necessarily think about how the world just crashed around you.”

Now, in time for Father’s Day delivery, she’s designed a limited, one-of-a-kind online offering: the Hope Collection. While all her creations are made from reclaimed materials—including airbag scraps, plastic bottles recovered from the ocean, and striking fabric remnants—for the Hope Collection, Blackwell’s raw material and inspiration are odds and ends of fabric left over from local protective mask-making efforts. “I found hope in taking action to piece things back together,” she says.

Blackwell didn’t set out to be a creative entrepreneur. She was well onto her path of becoming a registered nurse, when one day she was invited to a birthday party for a friend’s daughter. Not having a lot of money for a present, she got out the sewing machine she had bought but was too intimidated to use. She made small hair bows out of fabric she’d found thrifting over the years. They were such a hit that she left the party with orders to make more. Hair adornments led to bow ties in 2014, and her company Knotzland was born in 2015.

“Renew” and “Miami Nights” are part of Knotzland’s limited-edition Hope Collection.

The business side hasn’t come as easily as the intuitive creativity, she notes, and she’s benefited from a diverse set of business accelerator training programs and seed funding. “If I had all the money in the world, I would just make beautiful things and give them away,” she says. “But as a creative business owner, we have to make money because it has the power to not only create a livelihood for myself, but also people on our team.”

Blackwell hopes her success in turning her artistic instincts into a moneymaking venture will inspire other black women. In fact, she’s looking for someone to revive the hair ribbons that started it all. “It’d be nice to come across a protégé who loves hair bows to take over the hair-bow-making part of the business.”

Finding her voice in pottery

Reiko Yamamoto started making pottery when she moved from Tokyo to Detroit. She arrived at the end of her freshman year of high school and could barely speak a word of English. “My ability to communicate was rudimentary, and I felt like I didn’t belong anywhere,” she recalls.

She found her voice in a pottery class. “It was the only way I could be heard.”

The teenager quickly learned English, but she never stopped expressing herself through ceramics.

Yamamoto’s handmade tableware, each piece designed, made, and fired in her Sharpsburg studio, has clean lines that can be mixed and matched—the way people do in Japan, where she spent much of her globe-trotting childhood. “If you see something you like, you just buy it,” she says. “You don’t worry if it matches the set you already have at home. You build your collection piece by piece, and they complement each other.”

Reiko Yamamoto in her Sharpsburg studio. Photo: Ross Mantle

When she was pregnant with the first of her two sons, she decided to step up the focus on the business side of her practice, so she wouldn’t lose it with the constant demands of being a parent. “There was a little bit of fear of diving headfirst into motherhood, and 10 whirlwind years later, looking back and saying, ‘Oh, what just happened?’”

The ceramicist has found an artistic community in Pittsburgh. Her work intensified as her sons started school full-time and she began sharing a studio with two other artists. They help each other, she says, with the technical aspects of their craft, and they share resources and equipment.

Yamamoto’s pottery can be found around town, showcasing cuisine at foodie destinations such as Superior Motors in Braddock, Floor 2 in the Fairmont hotel, and Seasons in Etna. And guests at TRYP hotel in Lawrenceville might enjoy in-room coffee service from her handmade tumblers and cups.

During the stay-at-home order, she began making and selling Tiny Smiles, small, round, ceramic magnets with dots for eyes and a nose and a wee smile—not a full-blown happy face—as a tangible way to help her most vulnerable neighbors.

She first began making the small keepsakes in the fall of 2016. Distraught by the presidential election’s outcome, she figured she would make something to spread a little hope. “Just the act of making them made me feel better—a little smile. I couldn’t manage a big smile.”

She experienced a similar feeling of despair once the coronavirus upended the world, and so it was time again to make the tiny acts of hope.

“Just the act of making them made me feel better—a little smile.” – Reiko Yamamoto

By early June, she’d put more than 300 smiles out into the world—a reminder, she says, “to take a deep breath and find something to smile about”—with more than $3,000 in proceeds benefiting organizations such as the Greater Pittsburgh Community Food Bank, 412 Food Rescue, Sisters PGH, and the Women’s Center & Shelter of Greater Pittsburgh.

Studying birds—and love

Painter and mixed-media artist Ashley Cecil and her 6-year-old son came up with a fun art project—COVID-coloring—during the decidedly unfun days of sheltering in place at home. The first sketch was of a T. rex with tiny arms and a dialogue bubble that says, “I will survive. I can’t touch my face.” They dropped off the sketches at neighbors’ houses, and her son was thrilled when they came back filled in with bright colors. So, they continue to make original coloring pages, all printable from Cecil’s website.

During the stay-at-home order, Ashley Cecil shifted from depicting nature to studying human connection. Photo: Chancelor Humphrey

Simultaneously, Cecil, who is known for combining scientific accuracy with stunning artistry, was also collaborating with furniture designer Nick Volpe on the upholstery of Ode, a tubular steel chair inspired by Marcel Breuer’s 1928 Cesca. Part of the Museum of Art’s upcoming Locally Sourced exhibition, Ode’s frame is upholstered with a textile influenced by Cecil’s oil paintings of flora and fauna from Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

The repeating textile pattern features vivid yellow-headed blackbirds, jewel beetles, and butterflies—all based on museum specimens—as well as poppies, tropical water lilies, and impatiens. Some of Cecil’s inspiration comes from paintings she created during a six-month artist residency at the Museum of Natural History in 2016.

Combining her artistic ability with entrepreneurship comes naturally to Cecil. As a teenager in Kentucky, she started her own business painting murals in kids’ bedrooms. She was also an early nature lover who drew horses as a kid, and when she landed at the museum for her residency she focused on birds. Her hyperrealistic winged beauties, set against graphic backgrounds reminiscent of Victorian patterns, look like they could pop off the canvas and fly away.

“It’s been therapeutic to study the love happening in people’s homes.” – Ashley Cecil

Her art brings attention to environmental challenges, such as the millions of birds that die every year from collisions into windows. She joined museum scientists at Powdermill Nature Reserve, the museum’s biological field station in the Laurel Highlands, where they use a flight tunnel to test which window patterns made by glassmakers are visible to birds and will prevent collisions. Her textiles and paintings highlight the yellow-bellied sapsucker and other species often found lifeless under windows.

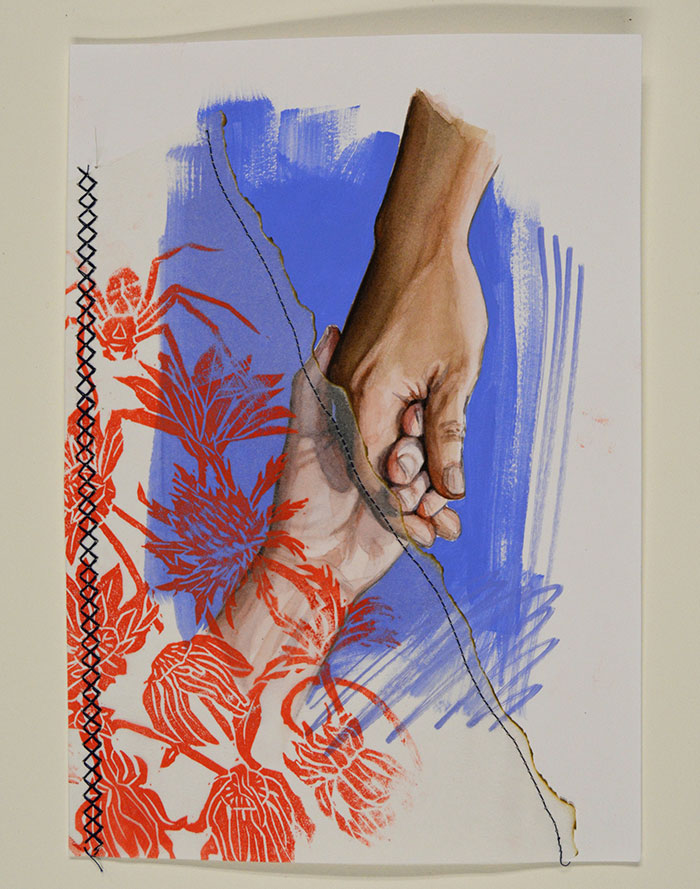

Hand in Hand 5

Over the past two months, Cecil has shifted focus, and is actively taking commissions for mixed-media portraits of clasped hands—a symbol of the broken ties of human connection during the COVID-19 outbreak. She collects photographs of the intertwined hands of people bonded together in quarantine—“love for one another,” says Cecil—and then paints them, sewing burned or torn tracing paper block-printed with a nature-themed pattern over top. She says hands are one of the hardest things for her to render and practicing daily is akin to a musician playing scales. She hopes to exhibit these “family portraits” someday. For now, a portion of the proceeds is supporting an emergency fund for artists.

“It’s been therapeutic to study the love happening in people’s homes,” says Cecil. “I’m resonating emotionally with people and also keeping my skills sharp.”