In the midst of suffering and loss, art is often born, its lifespan far exceeding that of its creators, its meaning changing and growing with every subsequent generation of viewers. By sharing personal perspectives of a universal experience, artists working in the shadows of tragedy can provide a light like no other.

“During times of crisis,” says Patrick Moore, director of The Andy Warhol Museum, “artists become conveyors of emotions that go beyond what can be read in textbooks or newspapers. Art plays a role, perhaps similar to religion, in that it helps us understand things that are too big to understand.”

History is full of such things, including pandemics.

COVID-19 may be a novel virus, but infectious diseases are far from new. One of the first known cases of a widespread contagion occurred during the Peloponnesian War in 431 B.C. Between then and the dawn of the 20th century, some 10 major outbreaks—ranging from the bubonic plague to cholera, smallpox, and yellow fever—left hundreds of millions dead in their wake.

Is it any wonder, then, that so many classic works of art depict scenes of mass burials, apocalyptic destruction, and lots and lots of creepy skeletons?

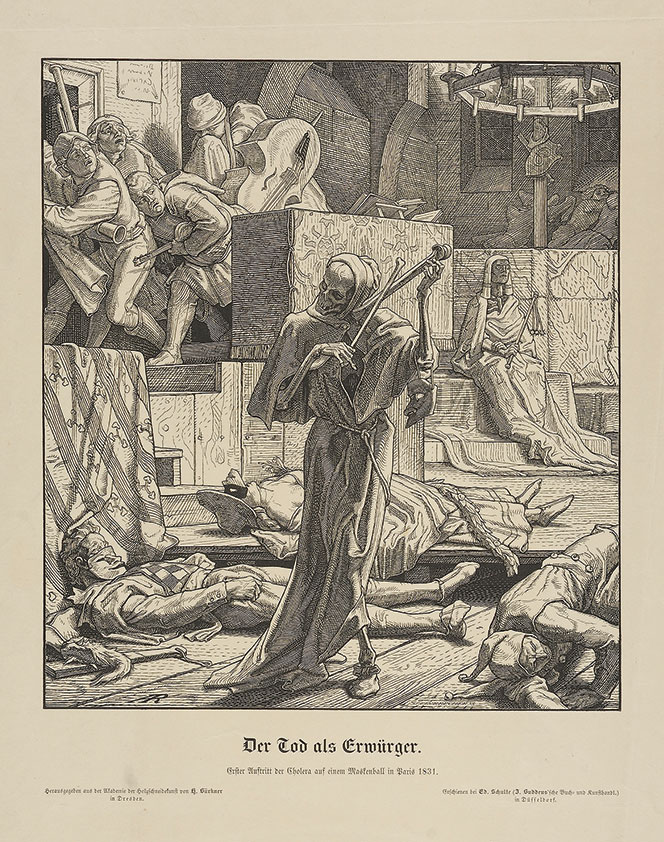

Carnegie Museum of Art has its share of artworks that reflect this sense of doom. The titles speak volumes: Young Couple Threatened by Death (Albrecht Dürer, 1498); The Rat Catchers (Cornelis Visscher, 1655); Death the Strangler, The First Outbreak of Cholera at a Masked Ball in Paris (Alfred Rethel, 1851); and Twenty-nine Victims of the Cholera Epidemic of 1858 (unknown Japanese artist, 1858).

Gustav Richard Steinbrecher after Alfred Rethel, Death the Strangler, The First Outbreak of Cholera at a Masked Ball in Paris, 1831, 1851, Carnegie Museum of Art, Leisser Art Fund

Fast forward to 2020. It seems that self-quarantining and stay-at-home orders are not only prompting us to gaze longingly out our windows but also to search for historic touchstones—moments that might be able to offer us context, guidance, and perhaps a closer look at our shared humanity.

After all, what’s past is prologue, right?

“It takes a certain amount of time and distance to fully see and understand art that comes from a crisis,” says Jessica Beck, The Warhol’s Milton Fine Curator of Art. “Just as it takes that kind of time and distance for us to understand what took place during that crisis, whether it was a war or a health or economic depression event.”

With a century of hindsight, time is certainly on our side when it comes to evaluating the 1918 influenza pandemic. One thing we’ve learned is that it’s impossible to separate the flu from the other catastrophic global event of the day: World War I. As the war was winding down, officially ending on November 11, 1918, the flu caused by the H1N1 virus was ramping up.

“It takes a certain amount of time and distance to fully see and understand art that comes from a crisis.” – Jessica Beck, The Warhol’s Milton Fine Curator of Art

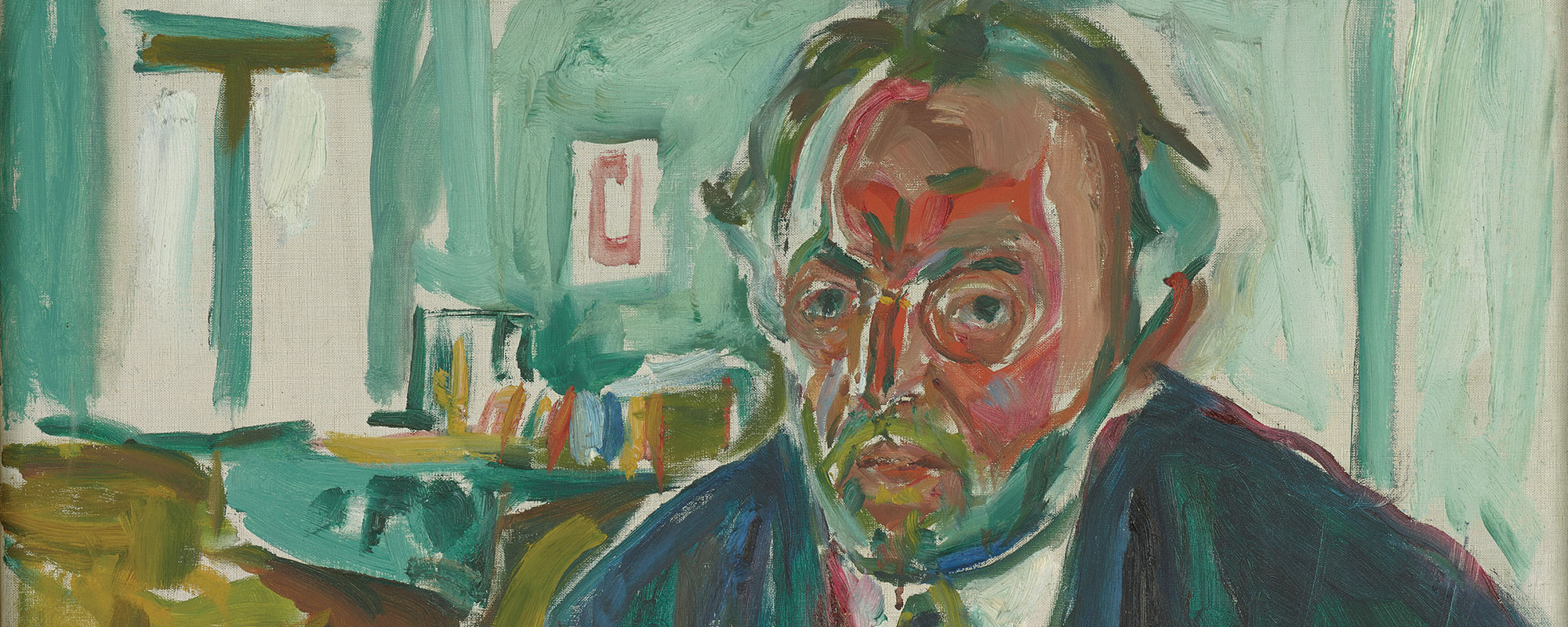

Among the artists who contracted the 1918 flu and survived was Norwegian painter Edvard Munch, whose self-portrait captures him wrapped in a gown and blanket, a corpse-like expression on his sallow face.

Edvard Munch, Self-Portrait with the Spanish Flu, 1919, National Museum of Art, Architecture, and Design, Oslo

For two harrowing years, its spread was inadvertently hastened by large troop mobilizations around the world. Ultimately, 500 million people—at the time, more than one-third of the earth’s population—were infected. An estimated 50 million died. In fact, for every doughboy killed in battle, 12 were lost to the flu. These staggering numbers earn the 1918 flu the dubious distinction of being the deadliest pandemic in history.

When it arrived in the United States in March 1918, its first victims were soldiers stationed at Camp Funston in Kansas. In two succeeding waves—in the fall and winter of that same year—it became clear that no town or city or even rural outpost was going to survive unscathed. An estimated 4,500 people in Pittsburgh, more than one in every 100 residents, died from the virus.

Given its destructive power, you might expect the flu of 1918 to be memorialized in art. It is, but art historians are still unraveling the connections.

How artists depicted disease

Thanks in part to the efforts of world leaders like U.S. President Woodrow Wilson, the flu was not a priority—winning the war was job one. That policy of silence contributed to its inaccurate nickname, the “Spanish flu.” As one of only a few nations that remained neutral throughout World War I, Spain didn’t suppress media coverage of the flu, and the Spanish media covered it with a vengeance, historically linking the country with the virus.

Monuments have been built to the war; look no further than the larger-than-life doughboy who stands guard over Lawrenceville. But few memorials to the flu and its victims, whether chiseled into stone or painted on canvas, exist.

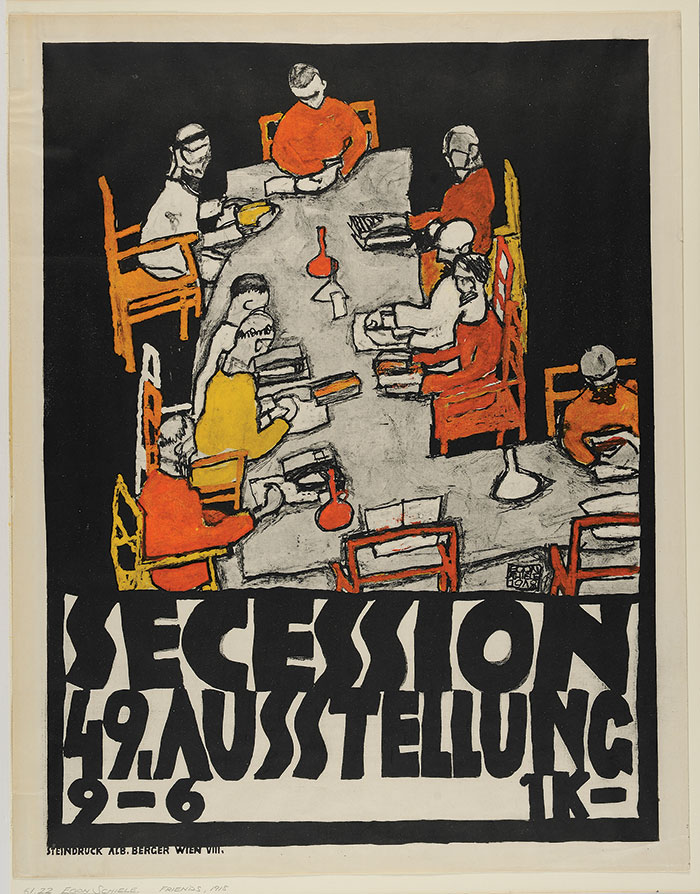

“We have zero direct references to the flu in our collection, but we do have a poster by Egon Schiele that was made to advertise the 49th Exhibition of the Vienna Secession group of artists held in 1918,” says Akemi May, Carnegie Museum of Art’s assistant curator of fine arts. Titled Friends, the lithograph shows people gathered around a table; Schiele sits at the head, across from him is an empty chair. “That chair,” May explains, “speaks to the loss of his mentor and friend Gustav Klimt, who died earlier that year from the flu.”

Egon Schiele, Friends, 1918, Carnegie Museum of Art , Gift of Sara M. Winokur and James L. Winokur

The more widely known examples are Edvard Munch’s Self-Portrait With the Spanish Flu (1919) and Self-Portrait after the Spanish Flu (1919–20) and Schiele’s The Family (1918). The family Schiele painted was his own. The nude bodies of the artist and his wife are seen crouched around a child, whose birth they were anticipating. But instead of joy their faces reveal a certain inevitability.

“Dear Mother Schiele,” he wrote. “Edith got the Spanish flu eight days ago and has pneumonia. She is six months pregnant. The disease is very serious and life-threatening; I am preparing myself for the worst.” Shortly after the letter was sent, the couple died three days apart.

Art at the epicenter of crisis

Nearly 65 years later, another pandemic gripped the world.

It’s widely believed that AIDS originated in the Democratic Republic of Congo in the 1920s. It remained relatively rare until the ’70s when it started spreading beyond Africa.

By 1981, the first official diagnosis was made in the U.S. and the acronym for acquired immune deficiency syndrome was adopted as a medical term the following year. President Ronald Reagan, however, would not publicly mention the word until a 1985 press conference. At that point, more than 13,000 Americans had died of AIDS.

As an openly gay man living in New York City in the ’80s, Andy Warhol could not escape the day-to-day realities of the rapidly escalating health crisis. In eight entries in The Andy Warhol Diaries, the artist refers to “the gay cancer,” a moniker provided by a 1982 New York Times article.

“Private lifestyles were becoming topics of public scrutiny, and homosexual men in particular were being targeted,” Jessica Beck says. “Warhol was petrified of AIDS, but what he seemed to fear most was the public shame of people thinking he was sick.”

Similar to our current crisis, the spread of the disease was not fully understood—casual contamination was first thought to be a possible mode of transference. Fear was everywhere, and there was a sense that there was nowhere to hide. No place—not even home—offered a safe haven. For Warhol, that became abundantly clear when his longtime lover, Jon Gould, contracted AIDS in 1984 and died two years later.

Warhol does not address Jon’s death directly, but Pat Hackett, editor of the Diaries, made this graphic mention of his passing. “NOTE: Jon Gould died on September 18 at age thirty-three after ‘an extended illness.’ He was down to seventy pounds and he was blind. He denied even to close friends that he had AIDS (Hackett 760).”

For Patrick Moore, that time period was like living in a war zone. “The concentration of the AIDS tragedy was like a bomb going off,” he recalls. “At the moment of the AIDS crisis, especially because I was working in the art world in New York, I was thrown together in a very intimate way, in a life and death way, with people I may never have encountered otherwise.”

By 1987, the year Warhol died from complications of gallbladder surgery, the death toll in the U.S. from AIDS had surpassed the grim milestone of 40,000 while the number of HIV infections throughout the world was, by some estimates, as high as 10 million. And yet, the Reagan administration continued to underfund research.

“There are certain moments when society is ready for a revolution and something like a health crisis becomes the catalyst for change. I think that was certainly true during AIDS.” – Patrick Moore, director of The Warhol

“Every single person I knew in the art world cared about the same things,” Moore says. “We cared about how to leverage what capital we had to find a cure, to find treatment. There was this sense of unity.”

In March of 1987, many people in the gay and artistic communities joined forces under the banner of the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power, better known as ACT UP. The group’s tactics were far from subtle. Members put their bodies on the line—standing in traffic, chaining themselves to politicians’ desks, and storming Wall Street meetings.

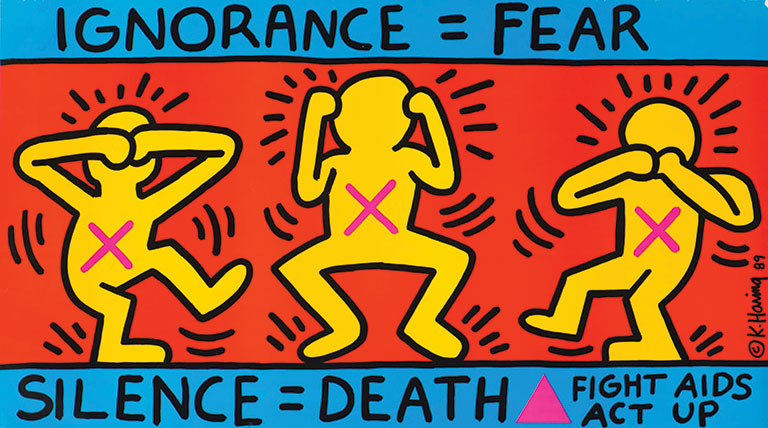

Silence = Death

Art was one of the weapons the newly formed coalition wielded. ACT UP activists created the slogan Silence = Death and turned the pink triangle, the one the Nazis used to humiliate homosexuals, into a symbol of pride. Artist Keith Haring’s vibrant colors, animated figures, and graffiti style brought all the elements together to form a singularly powerful message. Haring, who grew up in eastern Pennsylvania and went to the Ivy School of Professional Art in Pittsburgh for a short time, was diagnosed with AIDS in 1988 and died in 1990. He was 31.

Keith Haring, Ignorance = Fear / Silence = Death, 1989, Keith Haring artwork © Keith Haring Foundation

Other artists took a less overtly political point of view. Photographers in particular were able to capture the suffering endured by both the human body and spirit. Carnegie Museum of Art’s collection includes several compelling examples from Peter Hujar, who died of AIDS-related pneumonia in 1987 at age 53, and Nigerian-born Rotimi Fani-Kayode, who died in 1989 at the age of 34.

But perhaps it was Robert Mapplethorpe who most defied simple classification. The photographer came of age professionally before the AIDS crisis, his work unabashedly exploring the male body and queer life. Post- AIDS, he became a target for right-wing conservatives who believed the pandemic was nothing short of divine retribution. In 1989, Senator Jesse Helms led the successful charge to have Mapplethorpe’s work removed from public view at the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, D.C., due to its overtly sexual content. Mapplethorpe died in 1989. He was 42.

The lives and works of Warhol, Haring, and Mapplethorpe were inextricably linked.

Warhol created a silkscreen of Mapplethorpe. Mapplethorpe photographed Warhol and Haring. Warhol and Haring were friends and moved in the same downtown New York circles.

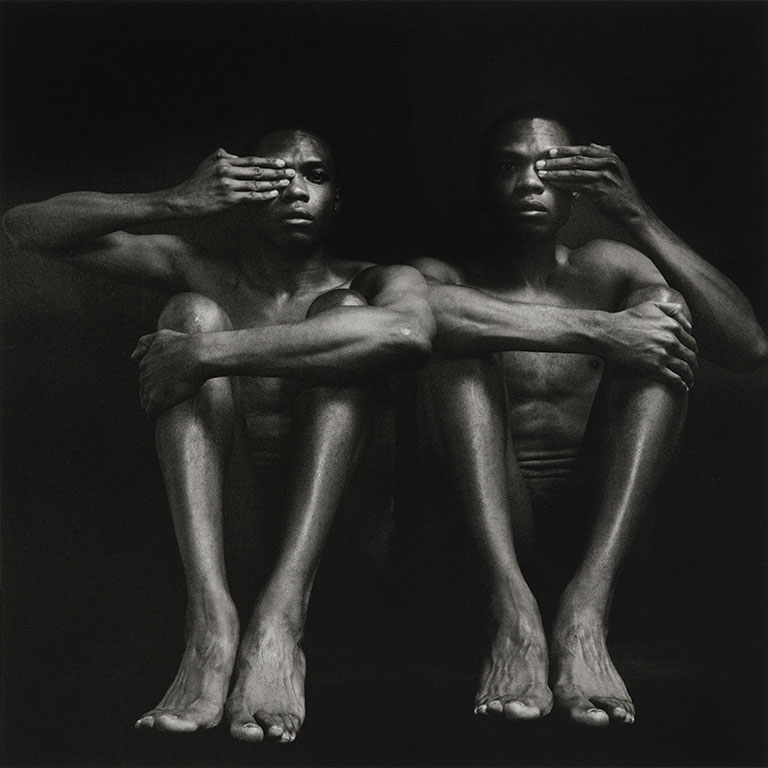

Working during the height of the AIDS crisis and responding to homophobia, Rotimi Fani-Kayode produced images that exalt queer black desire, call attention to the politics of race and representation, and explore notions of cultural identity and difference.

Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Half-Opened Eyes Twins, 1989, printed 2019, Carnegie Museum of Art, William Talbott Hillman Fund for Photography. Courtesy Autograph, London

Unlike Mapplethorpe and Haring, who have been remembered for their activism, Warhol has often been criticized for his lack of response to the disease. Time and distance have brought Beck to a different conclusion. “Warhol’s The Last Supper paintings,” she has written, “are a confession of the conflict he felt between his faith and his sexuality, and ultimately a plea for salvation during the mass suffering of the homosexual community during the AIDS crisis.”

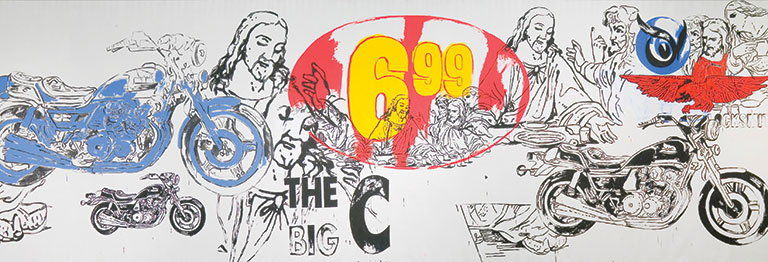

Commissioned by art dealer Alexander Iolas (who died of AIDS in 1987 at the age of 80), Warhol created more than 100 paintings based on Leonardo da Vinci’s masterpiece The Last Supper (1495–1498). It was Warhol’s last series of work.

Though the series is universally dismissed by critics, Beck sees them as redemptive, pointing to two paintings in particular—The Last Supper (The Big C) and AIDS, Jeep, Bicycle—to make her case.

“I think of them as sister canvases,” she says, “because they share the same source material of headlines and advertisements. These images of redemption and forgiveness Warhol was offering during this time of public suffering

and shame.”

Andy Warhol, The Last Supper (The Big C), 1986, The Andy Warhol Museum; Founding Collection, contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

As of 2018, 32 million people have died of AIDS, some 770,000 in the U.S., the World Health Organization reports; nearly 40 million people are living with AIDS.

“Warhol’s response wasn’t a failure,” Beck adds, “but a confession of love and fear and an expression of mourning. He gave AIDS a face—the mournful face of Christ.”

What will the face of COVID-19 look like? “It’s too soon to know,” says Moore. “There are certain moments when society is ready for a revolution and something like a health crisis becomes the catalyst for change. I think that was certainly true during AIDS. I think we’re ready for a revolution today, but I don’t know if this will precipitate it.”

Beck is hopeful about the work that will emerge from this time of isolation and change.

“We’ve all gone inside to reflect and heal, but after this period of mourning there will be great art,” says Beck, noting she’s had several recent virtual studio visits with artists.

“Everyone is afraid, but art can help us process the fear. Art also has the power to transform. Artists are letting their creativity flow, as a tool for survival, now more than ever!”

Receive more stories in your email

Sign upTags:

Art