In 1899, Claude Monet arrived at London’s swanky Savoy Hotel prepared to stay for months. Having reserved a room with a view, he quickly transformed the suite into a makeshift studio, perched his easel on the balcony, and, bracing himself against the winter cold, got to work.

As the panoramic vistas he observed along the River Thames revealed themselves anew seemingly every moment, the father of impressionism painted furiously—at turns frustrated and exhilarated. It was a routine the Frenchman would repeat two more times over the next two years, albeit from different rooms. After much speculation, Monet’s specific locations at the Savoy were confirmed in 2010, when an applied meteorologist at the University of Birmingham did the math. Using the sun’s trajectory, survey maps of London, and the city’s weather records, the scientist established that the renowned artist rendered his work from rooms 510, 511, 610, and 611.

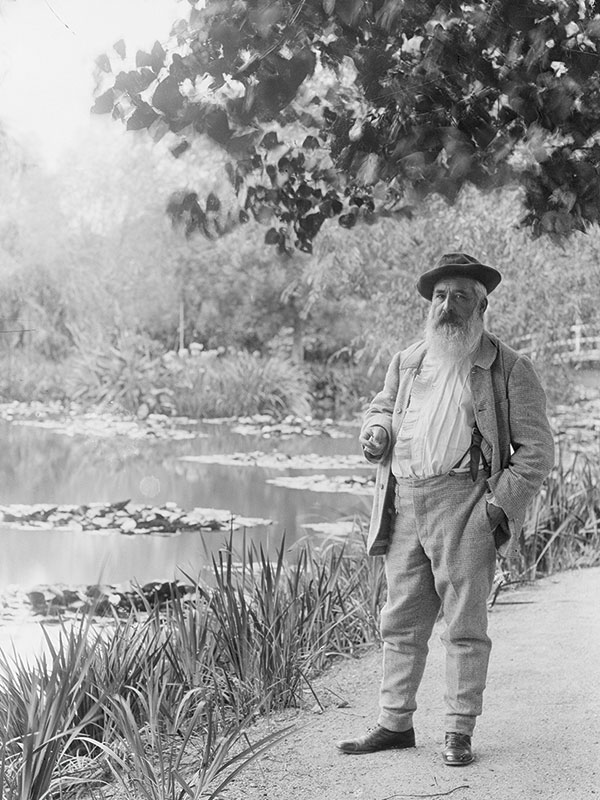

Claude Monet

At first glance, it might appear that the Waterloo and Charing Cross bridges—as well as the Houses of Parliament, which Monet painted from across the river at St. Thomas Hospital—were the primary focus of his London obsession, which realized 100-plus paintings. He produced more than 40 versions of Waterloo Bridge alone.

But it was the very air itself—filled with smog (although that word wouldn’t enter the common vernacular until 1905)—that he sought to capture on canvas.

“I am working very hard,” he wrote to his first wife, Camille Doncieux, in early March 1900, “although this morning I really thought the weather had changed completely; when I got up I was terrified to see that there was no fog, not even a wisp of mist: I was prostrate, and could just see all my paintings done for, but gradually the fires were lit and the smoke and haze came back.”

For Monet and many of his contemporaries, the smoke that accompanied society’s ever-increasing reliance on manufacturing set the scene for a more contemporary kind of beauty—the urban landscape.

That’s the theme of Monet and the Modern City, a relatively small but impactful exhibition on view through September 2 at Carnegie Museum of Art. In addition to master paintings by Monet and Camille Pissarro, it includes prints and drawings by Félix Buhot, Auguste Lepère, and James Abbott McNeill Whistler, among others, all of whom were equally inspired to capture the modern industrial environment.

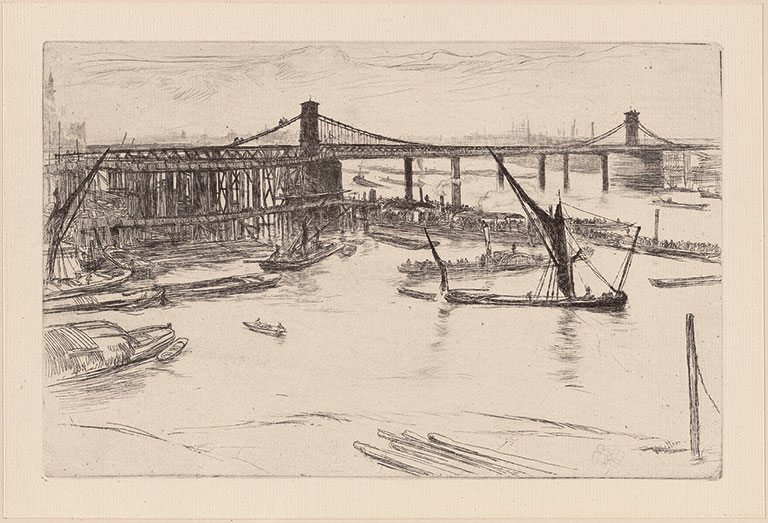

Checking into the Savoy a few years earlier than Monet, American-born Whistler was also drawn to London’s shifting surroundings, namely the Charing Cross railway bridge, Savoy pigeons, and the ever-bustling Thames.

Camille Pissarro, The Great Bridge, Rouen (Le Grand Pont, Rouen), 1896, Carnegie Museum of Art, Purchase

James Abbott McNeill Whistler, Old Hungerford Bridge, 1861, Carnegie Museum of Art, Purchase

Above: Like Monet, many of his contemporaries, including Camille Pissarro and James Abbott McNeill Whistler, found inspiration in the urban landscape.

Strength in numbers

Clearly, at least some of the effects of the industrialized city fueled a passion in the artists of the day—namely Monet.

“We’re seeing Monet obsessed with the atmospheric effects of fog and smoke and light on the Thames, on this view from his window of London’s industrialized South Bank,” says Akemi May, the museum’s assistant curator of fine arts and organizer of Monet and the Modern City. “We’re getting Monet’s impression of those effects on the city.”

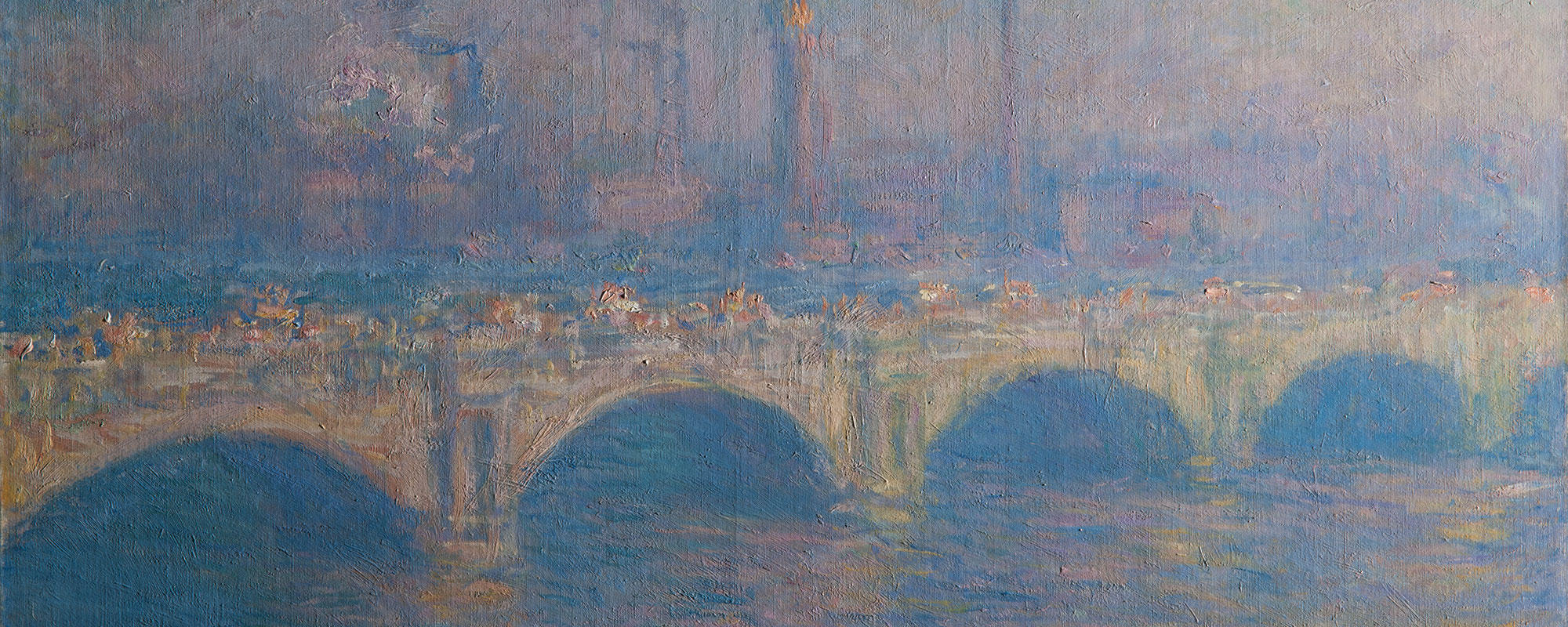

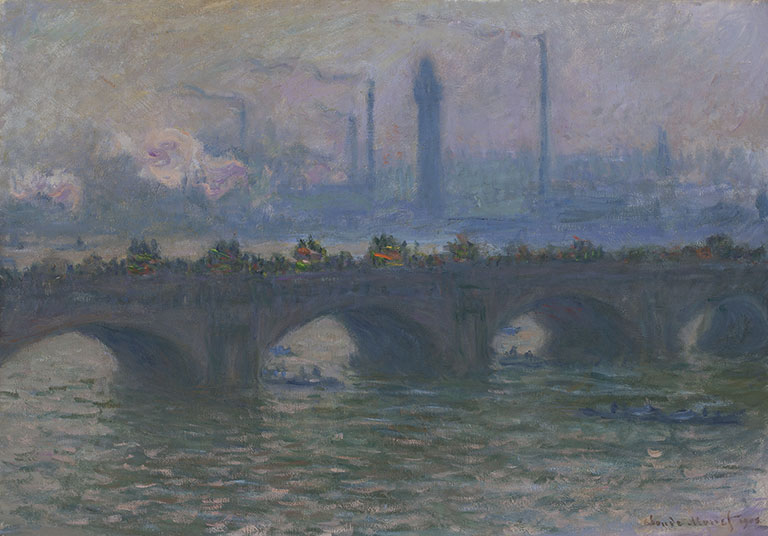

Enter the stars of the exhibition—Carnegie Museum of Art’s own Waterloo Bridge presented alongside two others from the same series, on loan from the Worcester Art Museum and the University of Rochester’s Memorial Art Gallery, where the inspiration for Monet and the Modern City originated.

Claude Monet, Waterloo Bridge, London, 1903, Carnegie Museum of Art, Acquired through the generosity of the Sarah Mellon Scaife Family

Claude Monet, Waterloo Bridge, Veiled Sun, 1903, Memorial Art Gallery of the University of Rochester, Gift of the Estate of Emily and James Sibley Watson

Claude Monet, Waterloo Bridge, 1903, Worcester Art Museum, Worcester, MA, Museum Purchase

Above: Monet and the Modern City spotlights three very different paintings of the exact same

Nancy Norwood, the Memorial Art Gallery’s curator of European art, says the goal of their show, Monet’s Waterloo Bridge: Vision and Process, was to offer viewers a slow-looking experience. “We wanted to encourage people to think of Monet’s paintings,” she says, “in the way he thought of them—as a unit—and that each one should be seen in relation to the others.”

From Monet’s perspective, that meant returning to the same scene over and over again, at different times of day and year in an effort to truly realize its complexities and subtleties. And so, in the 1880s he famously started painting in series: Haystacks (30 studies), Rouen Cathedral (30+), Venice (37), and, of course, Water Lilies (250). Carnegie Museum of Art is home to Water Lilies (Nymphéas).

It was a painstaking process. “You’ll understand, I’m sure that I’m chasing the merest sliver of color,” Monet said. “It’s my own fault. I want to grasp the intangible. It’s terrible how the light runs out. Color, any color, lasts a second, sometimes three or four minutes at most.” He stood on the Savoy balcony and almost instantaneously put his initial impressions of the Waterloo Bridge on canvas. But he considered the paintings incomplete and had them shipped back to France where he continued to labor over them.

“There’s this perception, perpetuated by Monet himself, that he’s totally in the moment. But that’s false,” May says. “He struggled with these for years, inventing and perfecting, and didn’t allow any of them to be exhibited until 1904. That’s why many paintings in this series have later dates ascribed to them. It took him a long time to be satisfied.”

“We’re seeing Monet obsessed with the atmospheric effects of fog and smoke and light on the Thames, on this view from his window of London’s industrialized South Bank.”

– Akemi May, Carnegie museum of art’s assistant curator of fine arts

Although some works never did meet his standards, the sum of all the parts—or even just three of the parts—is extraordinary to behold. That’s something the Memorial Art Gallery exhibition affirmed when it displayed nine Waterloo Bridge paintings together.

“I heard this over and over again and I was shocked that I felt this way, too,” Norwood says. “Walking into that room and seeing them together—people got chills. It’s really an experience, an experience you don’t get very often.”

Now, visitors to Monet and the Modern City get their chance to see—in a side-by-side comparison—how the yellows and oranges of Carnegie Museum of Art’s Waterloo Bridge give way to the purple and blue tones of the painting owned by Rochester, only to then be engulfed by the bold greens of Worcester’s masterwork.

They’re three very different paintings of the exact same motif—light, water, and atmosphere.

“And they’re incredibly beautiful,” says May. “From a technical standpoint, the technique and approach, Monet is able to do remarkable things. The effects are so ephemeral.”

Those effects are even more visible via an interactive display, thanks to conservation scientists in the art conservation program at Buffalo State University who conducted new imaging and materials analysis on the Waterloo owned by the Memorial Art Gallery. The experts’ insights provide a palette of infrared and ultraviolet lights that allows visitors to examine several Waterloos in high-resolution detail. In another interactive, visitors can channel their inner Monet by applying different color filters to create a personalized Waterloo Bridge.

The fog of steel

Just as Monet was enthralled by the London skyline circa 1900, so, too, were artists fascinated by the Steel City’s once sooty rivers, hillsides, and mills. A number of works by Norwegian impressionist Frits Thaulow, French printmaker Jean-Emile Laboureur, and Americans Aaron Gorson, Joseph Pennell, and pioneering modernist Joseph Stella are included in the exhibition.

One work in particular was designed to take into account the human aspect of industry. Stella’s Bridge, a charcoal drawing featuring a barely visible 16th Street Bridge, was commissioned by the Pittsburgh Survey to help illustrate the “conditions of life and labor of wage-earners of the American steel district.” That was in 1908.

Johanna K. W. Hailman, Jones and Laughlin Mill, Pittsburgh, c. 1925–1930, Carnegie Museum of Art, Bequest of Johanna K. W. Hailman

Aaron Henry Gorson, Pittsburgh at Night, c. 1920, Carnegie Museum of Art, Gift of Milton Porter, by exchange

Joseph Stella, Industrial Scene, New Jersey, 1920, Carnegie Museum of Art, Director’s Discretionary Fund

Forty years later on October 27, the mill town of Donora, Pennsylvania, about 25 miles south of Pittsburgh, was engulfed in a thick, green smog that over the course of five days killed 20 people and caused respiratory problems for thousands. Just four years after that, the Great Smog of London settled over the city with even more devastating results. Some experts assert that the catastrophic event claimed up to 12,000 lives, hastening the deaths of the young, elderly, and those already suffering from respiratory illnesses.

In the wake of these incidents, Parliament passed the Clean Air Act of 1956. The U.S. Congress didn’t approve its first Clean Air Act until 1963.

“Today, it’s hard not to think about these images in terms of the pollution,” May says, “and how that has affected our environment, our air quality, and the living conditions and health of the people. This is something that we, especially in Pittsburgh, continue to struggle with.”

Most recently, in late December 2018, a fire at U.S. Steel’s Clairton Coke Works significantly damaged its gas-fed operations and pollution controls, leading to spikes in pollution levels in the area. It triggered the Allegheny County Health Department to issue an air quality advisory urging residents with pre-existing respiratory and heart conditions, along with children and the elderly, to limit outdoor activity. Already, the childhood asthma rate in Clairton is above 22 percent, more than twice the state average and nearly three times the national average.

“Today, it’s hard not to think about these images in terms of the pollution, and how that has affected our environment, our air quality, and the living conditions and health of the people. This is something that we, especially in Pittsburgh, continue to struggle with.”

– Akemi May

The American Lung Association’s 20th annual State of the Air, released April 23, said air quality in the Pittsburgh metro area is getting worse. The 12-county region saw increased levels of ozone pollution, as well as more daily and long-term fine-particle pollution, which includes the chemicals in exhaust and the byproducts from burning wood and trash.

Is it still possible, then, to see the beauty in the romanticized smog of industry painted by Monet and his contemporaries? May says yes.

“I can separate the way I look at these paintings, separate my own feelings,” May says, “and admire what these artists were attempting to do.”

From where Monet stood—on the balcony of the Savoy—there was no doubt. “Without the fog,” said Monet, “London would not be a beautiful city. It is fog that gives it its magnificent amplitude … its regular and massive blocks become grandiose in that mysterious mantle.”

Major support for Monet and the Modern City is provided by Citizens Bank, Ritchie Battle, and Elizabeth Hurtt Branson and Douglas Branson.

Receive more stories in your email

Sign upTags:

Art