Scott McGuire’s mind was razor-sharp, but he was trapped inside a body that was deteriorating every day.

In 1997, the Greater Latrobe Area High School biology teacher was shocked to learn that tremors in his chest and his difficulty lifting weights were early symptoms of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), commonly known as Lou Gehrig’s disease. By 2001, the once active outdoorsman couldn’t walk. He eventually couldn’t say a word. He couldn’t even move his fingers to type. His frustration grew as he became physically and mentally abused by a caretaker but couldn’t speak up about it. “I felt more and more alone,” he recalls. “I was just staying alive.”

Then he watched a news segment about a man with a similar condition who used a communication tool—a device with eye-tracking technology. Right away, McGuire knew he had to have one. His neurologist referred him to Tobii Dynavox, a Swedish company with headquarters in Pittsburgh that sells a variety of high-tech speech generating devices, including specialized tablets like the one McGuire saw on TV.

Scott McGuire communicates using an eye-tracking, speech-generating device. He’s pictured here with best friend and caregiver, Maria. Photo: Courtesy Tobii Dynavox

By moving his eyes to focus on different letters, symbols, and phrases on an on-screen keyboard, McGuire has reclaimed his voice. He uses his device to write sentences, which are converted to a deep baritone voice. He also uses it to send text messages, design greeting cards, play poker, and even change the channel on his TV.

“Tobii Dynavox saved my life,” he says, his words delivered through the speakers of the device. “When all you can move is your eyes, it makes the learning curve really short once you are positioned correctly. It’s basically point and shoot. It’s really that easy.”

The hands-free communication aid is on view at Carnegie Museum of Art as part of Access+Ability, an exhibition featuring research and designs developed over the past decade with and by people who span a range of physical, cognitive, and sensory abilities. On display in the Heinz Galleries through September 8, the show was organized by the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum in New York City.

“Tobii Dynavox saved my life. When all you can move is your eyes, it makes the learning curve really short once you are positioned correctly. It’s basically point and shoot. It’s really that easy.”

– Scott McGuire

Its central theme: design matters. And it’s not about designing for difference. It’s about function, practicality, style, and choice—for all. From all-terrain wheelchairs, bedazzled hearing aids, and a shirt that enables people who are deaf to feel classical music, the products—low-tech, high-tech, and some still prototypes—represent the future of accessibility design.

“People may be surprised to come into the galleries and see canes and digital communication devices,” says Rachel Delphia, the Alan G. and Jane A. Lehman Curator of Decorative Arts and Design at Carnegie Museum of Art. “What drew me to this exhibition is that, as you dive into each and every object, there is a human story that inspired its creation.”

Seeing With Your Tongue

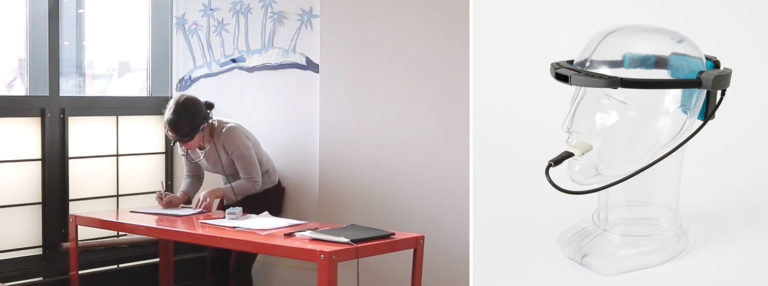

Artist Emilie Gossiaux used the BrainPort Vision Pro to get back to her passion: drawing. Photo: Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum

Emilie Gossiaux was a 21-year-old artist riding her bike to a New York City studio in 2010 when an 18-wheeler truck struck her. After the catastrophic accident, she was admitted to the intensive care unit in a coma. Initially, the prognosis was so bleak that a nurse approached her mother about organ donation. Over time, she emerged from the coma, but then the family received more news: Gossiaux, who had worn hearing aids since age 6, had lost her vision.

Over the next weeks, her boyfriend devised a way to communicate with her by tracing letters on her palms. Gossiaux responded by speaking. But she still had to learn to navigate her world without eyesight, and for Gossiaux, that meant returning to her lifelong passion for art. “I didn’t think my blindness would stop me from making art,” she says. “I knew it would be different and I would learn different skills.”

Two years later, while Gossiaux was at a rehabilitation center relearning basic skills, she was introduced to the BrainPort Vision Pro. The high-tech glasses are equipped with an outward-facing camera with a remote control attached to a device containing hundreds of electrodes that rests on the tongue. To Gossiaux, the signals felt like fizzy Coke tickling her tongue, but over time she learned to interpret the strength and shape of the bubbling sensations as pictures of her surroundings— like light and dark, shapes of objects, and the outlines of people walking on a sidewalk.

“I didn’t think my blindness would stop me from making art. I knew it would be different and I would learn different skills.”

– Emilie Gossiaux

She used the BrainPort for about a year to get back to drawing and to view sculptures at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where she led gallery tours. To draw, says Gossiaux, “I would zoom the camera in very close to the pen or marker, follow the line with the camera by moving my head, as if I could see with my eyes, and connect the lines. The sensation of the electrodes lightly shocking my tongue gave the impression of vision; I was seeing the drawing in my mind, or visual cortex. Then I would zoom out to look at the whole drawing and make my final marks.”

Two of her black-and-white drawings—one of a dog and one of palm trees—are on view in Access+Ability alongside the BrainPort.

For the love of a husband—and sneakers

Maura Horton runs her company, MagnaReady, out of her home in North Raleigh, North Carolina. Her next product to include magnetic fasteners is children’s coats. Photo: Chris Seward/Raleigh News & Observer/MCT via Getty Images

Don Horton, an assistant football coach for North Carolina State University, was running late for a game. Having lost his fine motor skills to Parkinson’s disease, he couldn’t button his dress shirt. Fortunately, one of his players in the locker room saw him struggling and discreetly buttoned it for him.

When the beloved coach relayed the experience to his wife, Maura, she could see the humiliation and panic in his eyes. What if it happened again during the next game or during a recruiting trip?

Maura, who used to design girls’ dresses, vowed to come up with a solution. The inspiration came from the magnetic closure of an iPod case: She could hide tiny magnetic closures behind the buttons on a shirt. Her invention, which is part of Access+Ability, gave her husband the dignity of dressing without help, and she knew many others would also benefit.

“My husband wore the prototypes and gave me immediate feedback,” she says. To stave off copycats, Maura applied for patents before launching MagnaReady, a magnetic apparel company, in 2013. Don wore the designs for three years before he died in 2016.

MagnaReady has sold 50,000 shirts, prompting Maura to expand the product line to include pants, which have also been popular. With its tagline of “dress with dignity,” MagnaReady has tapped into the growing adaptive clothing market. Coresight Research, a market research firm for the retail industry, estimated that the potential for adaptive clothing in the United States will reach $47.3 billion in 2019 and grow to $54.8 billion by 2023.

For Maura, the greatest joy of her job is getting letters from customers who have reclaimed a level of independence through use of her clothing.

She recently received a note from the mother of a boy with cerebral palsy who had achieved one of his benchmarks for independent living—putting on his own shirt and pants. “He was super psyched about that,” Maura says. Other letters have come from people suffering from arthritis and other chronic conditions.

The show also includes a pair of sneakers, Nike FlyEase, inspired by a teenage boy with cerebral palsy who wrote to the athletic giant saying he wanted to be able to put on his shoes by himself. The shoes feature a wraparound zipper at the heel, requiring no laces and making them far easier for someone with a movement disorder to put on and take off. The slam dunk: they’re also super stylish.

FlyEase shoes were inspired by Matthew Walzer, a teen with cerebral palsy, who wrote to Nike to help solve the challenge of tying his shoelaces. The result: a shoe with a wraparound zipper system that allows easy entry and exit of the foot from the back rather than from above.

Delphia notes that both inventions are good examples of universal design.

“Each starts with one person’s story and becomes a product that has the potential to reach so many other people,” she says. “When you design for the most challenging case, you end up with a product that is useful for a wider audience.”

Style and Choice

Just as eyeglasses are available in an array of colors and styles, hearing aids can be transformed into a personalized accessory. These 2014 designs, which include Swarovski crystals, are by Elana Langer. Photo: Hanna Agar

Forget medical aids that are clunky and clinical. The wave of the future, Access+Ability shows us, is style and choice. The exhibition showcases products that destigmatize assistive aids by turning them into fashion accessories.

Take compression socks, once only a dull beige or black. They’re now vivid and graphic. After all, they’re used by a wide variety of consumers, including the elderly, travelers, athletes, pregnant women, and runway models. Also newly chic—customized prosthetic leg covers that adorn and add a human silhouette to artificial limbs. Intended as a fashion statement, the goal is to provide amputees with color and pattern options.

Elana Langer, a conceptual artist based in New York City, is known for her glamorous assistive products. The idea started when her beloved grandmother, Ester, refused to go out while using a walker.

“She was a very classy lady,” says Langer. “She told me, ‘I won’t be one of those old ladies.’ Her pride was in how impeccably she presented herself. I saw the pain in her eyes.”

Langer promised her grandmother, “I will make you the most beautiful walker. You will be the talk of the town.”

Ester still refused the walker, no matter how glitzy, but Langer couldn’t let go of the idea. After her grandmother died, she ran with the concept, decorating not only walkers and canes but also hearing aids. The concept went viral after photographer Hanna Agar took photographs of Langer using her products in everyday situations, including one where she’s posing with a glamorous walker in a black bra and garter and stockings.

“I’m making something beautiful out of something you might be ashamed of. We’re looking at the aids as tools of life, and we honor them with beauty,” says Langer, who makes custom designs. Two of her hearing aids bedazzled with Swarovski crystals are on view in Access+Ability.

As Delphia puts it, “We are all growing old. We all get sick, and we all get injured. These objects find their way more and more into the mainstream. This exhibition helps build awareness and empathy about the need to be inclusive.”

[URIS id=7182]

Making Pittsburgh—and beyond—more accessible

Chieko Asakawa uses Out Loud, The Warhol’s inclusive audio guide, which employs NavCog technology.

Chieko Asakawa was 11 years old when she hit her left eye on the side of a swimming pool, damaging her optical nerve. By age 14, she was completely blind. The young athlete went from dreaming of participating in the Olympics to suddenly needing assistance with basic tasks. “I couldn’t go anywhere by myself and I really wanted to be independent and freed from relying on other people,” says Asakawa. “When I started out there was no assistive technology. I couldn’t read any information by myself. This led me to technology and, later in life, to innovate.”

Today the computer scientist is one of the world’s leading accessibility researchers. She’s currently based in Pittsburgh, and her pioneering efforts are benefiting local partner institutions, including The Andy Warhol Museum, Carnegie Mellon University (CMU), and Pittsburgh International Airport.

“When I started out there was no assistive technology. I couldn’t read any information by myself. This led me to technology and, later in life, to innovate.”

– Chieko Asakawa, accessibility researcher

An IBM Distinguished Service Professor in CMU’s Robotics Institute and an IBM Fellow at IBM Research, Asakawa is best known for developing the Home Page Reader—the first practical voice browser that allowed blind and visually impaired users to navigate the internet. The web-to-speech system debuted in Japan in 1997. By 2003, it was translated into 11 languages and widely used around the world.

Asakawa’s own desire for independence drives her groundbreaking work. Her early projects provided the blind community in her home country of Japan with access to braille books. She also developed a Japanese to braille translation system, as well as a disability simulator that gives sighted web developers the ability to mimic the experience of blind users. More recently, Asakawa and a team of student researchers at CMU debuted NavCog, an open-source smartphone app that helps people with visual impairments navigate their surroundings.

NavCog operates much like the turn-by-turn directions of GPS systems by analyzing signals from Bluetooth beacons and smartphone sensors to help users navigate indoor locations. The technology was piloted in 2016 as part of Out Loud, The Warhol’s inclusive audio guide that gives users perspectives on artwork and information on Andy Warhol as they navigate the museum’s seventh-floor gallery. It’s also in use on CMU’s campus, in a Japanese shopping mall, and at Pittsburgh International Airport.

Eventually, she says, the idea is not to rely on Bluetooth technology but to use cameras for computer-aided vision. Also in the works: the ability for users to identify passersby they may know using facial recognition—and even note if the person seems happy or sad. “The socialization aspect is crucial and a very big challenge,” says Asakawa.

Her latest undertaking with IBM: the “AI suitcase”—a lightweight navigational robot designed to steer a person who is blind through the complex terrain of an airport, providing step-by-step directions as well as information on flight delays, gate changes, and even dinner and shopping options. Still in the prototype stage, the carry-on AI suitcase has a motor embedded so it can move autonomously, an image-recognition camera to detect surroundings, and LIDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) for measuring distances to objects.

“I want to really enjoy traveling alone,” says Asakawa. “That’s why I’m focusing on the AI suitcase, even if it is going to take a very long time. It’s innovative and practical.”

– Julie Hannon