I like to think Carnegie Museum of Art’s collection is as much an assembly of artists as it is an assortment of objects, so the artist’s role in contemporary life always informs how I approach my work. How do artists respond to the social and political conditions that shape our world? How do they reinvent traditional mediums and question received notions? How do they give shape to dreams and subjective visions? And how do they embody forms of resistance and even protest?

The evolving and critical role of the artist is as multifaceted as the collection itself, so as a curator I try to convey the complexity of artistic decision-making as a very special form of thinking in the world, one that sheds light on postwar and contemporary conditions of being.

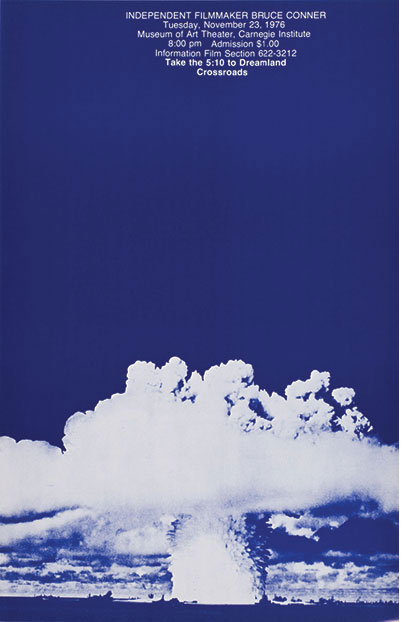

Poster for a 1976 screening of Bruce Conner’s CROSSROADS

The late American artist Bruce Conner—a maverick of sorts—is one of those figures who I have long admired for charting his own distinctive path. Best known for his avant-garde collage films, Conner was featured in the 2008 Carnegie International, and in the 1970s he often came to Pittsburgh to screen films as a visiting artist in the museum’s department of film and video.

Our reinstallation of the museum’s postwar and contemporary art galleries, slated to open on July 20, takes its name from one such film screened by Conner in the Museum of Art Theater on November 23, 1976. CROSSROADS is a 40-minute collage of declassified military footage of underwater atomic bomb tests at Bikini Atoll in 1946. It is a troubling and hypnotic film in slow motion set to original music by Patrick Gleeson and Terry Riley.

As you absorb this work of art, your mind toggles back and forth between the sheer abstract beauty of the archival imagery and the horrifying, destructive reality captured by the camera. Conner’s title is a reference to the U.S. military’s code word for the tests—“Operation Crossroads” —but, freed from its historical context, the title resonates differently.

Conner’s engrossing film looks back in time but also looks forward. While it points to a pivotal juncture in world history, it signals art’s unique ability to forge new ways of relating past and present. Across the collection more broadly, Conner’s notion of a crossroads might also suggest the intersection of history, society, politics, and biography—intersections that occasion creative acts and locate them in time.

Mining the collection

Working as a curator involves a great deal of time spent researching the collection in our art storage facilities. Frequent visitors to the museum are familiar with our displays in the Scaife Galleries, but they may be surprised to find what is stored away.

Imagine a vast room with hundreds of paintings hanging salon-style on moveable screens. As you wander through, the sheer diversity of the collection unfolds in front of you. It’s a bit of a mashup, honestly, like the results of a Google Images search.

Our registrars and conservators organize storage for practical reasons such as size and accessibility, so art history gets tossed out the window. Our Jackson Pollock painting, for example, might neighbor 19th-century landscapes, while Carnegie International prizewinners hang alongside minor works that have never been displayed.

Eric Crosby in painting storage, which houses more than 1,000 objects, including about 800 paintings. Photo: Bryan Conley

One of my responsibilities is to imagine the many different stories our collection of modern and contemporary art can tell, and I find these encounters in storage rousing. They get my synapses firing differently. I can set aside my assumptions and see the collection for what it truly is: a curious gathering of stories, histories, relationships, and choices.

One of the stories we know very well is the important relationship between the museum’s permanent collection and the Carnegie International. Once an annual exhibition and now occurring every four or five years, the International offers a curated snapshot of the art of our time, and many directors and curators have identified iconic acquisitions from it.

The history of donors giving art to the museum is also remarkable. Pittsburgh has been and continues to be very generous. Longtime supporters, collectors, and artists regularly identify significant gifts that evolve the collection in lasting ways. And then there are the frequent purchases that curators make from our exhibitions, such as the ongoing Forum series dedicated to contemporary art, and the continuing work we do to “fill historical gaps,” as we say. (Collections develop idiosyncratically, so periodically casting a glance back in time to see what we may have missed can shed light and guide future choices.)

These different collection-building threads converge in our galleries in surprising ways, and this is certainly true of Crossroads.

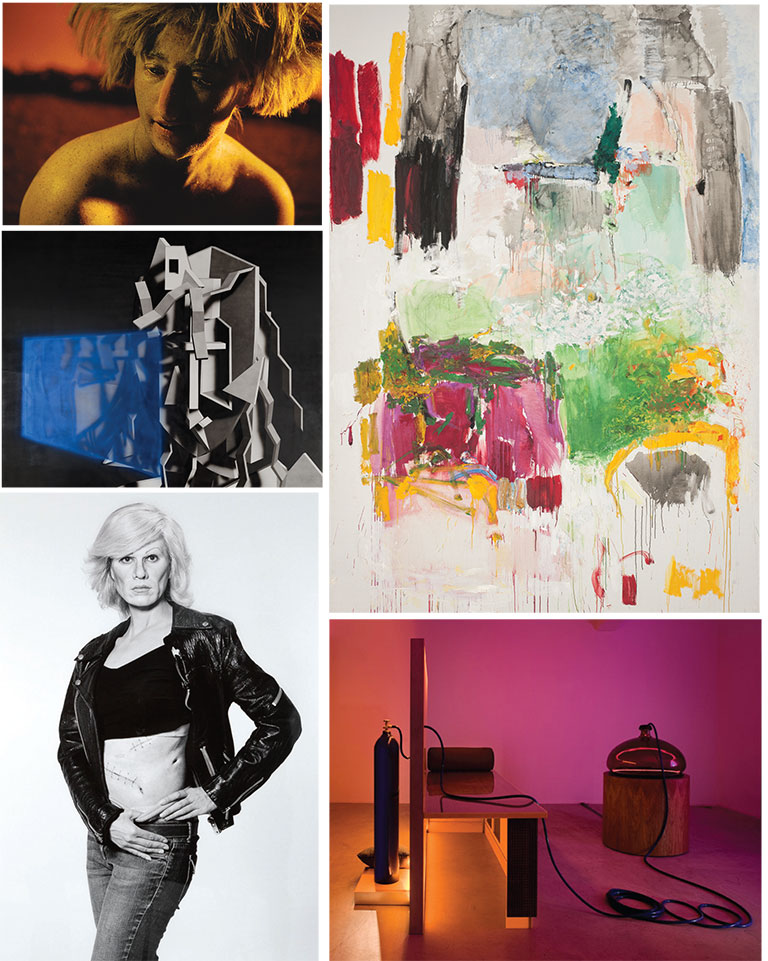

Cindy Sherman, Untitled #147, 1985, Pamela Z. Bryan Fund, Courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures, New York; Avery Singer, Untitled, 2016, Second Century Acquisition Fund and the Joseph Soffer Family Trust Fund; Gillian Wearing, Me as Warhol in Drag with Scar, 2010, Owned jointly by The Andy Warhol Museum and Carnegie Museum of Art, Purchased with funds provided by the Fine Foundation; Joan Mitchell, Low Water, 1969, Patrons Art Fund © Estate of Joan Mitchell; Mike Kelley, Kandor 20, 2007, The Henry L. Hillman Fund © Kelley Studio, Inc.

When I came on staff in 2015, I immediately delved into the collection and began researching new possibilities for its interpretation and display. I convened a cross-departmental working group of educators, archivists, curators, and editors, and we discussed the collection’s strengths and weaknesses, the distinctive features of our gallery spaces, and underrepresented voices and stories that lay dormant in storage.

Together, we asked, how might we reinvigorate our collection display and amplify the relevance of contemporary art in our current moment? History, like the present, is always in flux, so we agreed we wanted a permanent collection that feels less linear, less authoritative—in short, well … less permanent.

Of course, a great many of our most iconic works will always remain on view. They define the collection. However, now visitors will encounter them in new contexts.

New galleries, new ideas

Zao Wou-Ki, Black Crowd, 1954, Gift of G. David Thompson © 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ProLitteris, Zurich

We conceived Crossroads as a sequence of chapters, or episodes, that mine the depth, diversity, and eccentricities of the collection. Each corresponds to a reconfigured gallery space with focused interpretive texts. While the chapters figure roughly into a chronology from 1945 to now, they are, first and foremost, idea-driven and centered on the experiences of artists.

Some of these chapters explore how artists have responded to historical shifts and social flashpoints of the 20th century with pivotal innovations in visual art. For example, our first gallery offers an expanded presentation of the museum’s Abstract Expressionist masterworks, including works by Mark Rothko, Morris Louis, and Jackson Pollock. These and many other artists working in the immediate postwar period around the globe reckoned with a new world order and invented approaches to abstraction that reflected a tumultuous period in human history.

We might ask, how do these forms of abstraction reflect international postwar identities? Carnegie Museum of Art’s collection is particularly rich in this area, so for answers we can look beyond the American context to Jiro Yoshihara of the Japanese Gutai group who gave painting a performative dimension, or to Zao Wou-Ki, a Chinese émigré painter working in Paris, who infused Western abstraction with a lyrical and calligraphic sensibility.

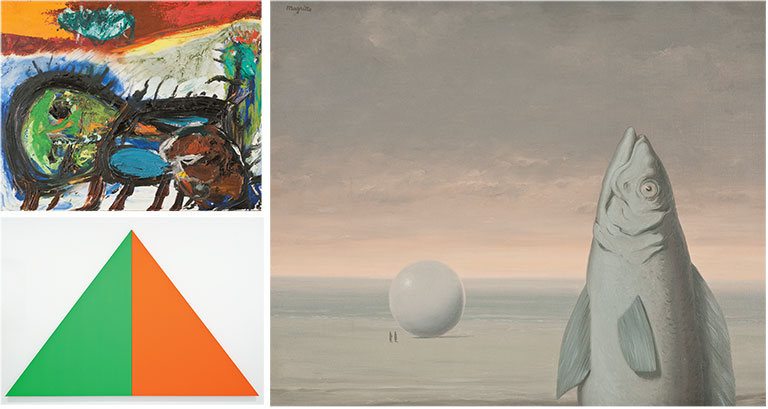

Similarly, we can look to Northern Europe and the so-called CoBrA group—a name that evokes the animal world and serves as an acronym for the cities Copenhagen, Brussels, and Amsterdam. In the 1940s and 1950s, poets and painters such as Asger Jorn and Pierre Alechinsky came together in collective response to the trauma of World War II with an all-out embrace of symbols, figures, animals, and myths to rediscover the origins of creativity. Carnegie Museum of Art has one of the most in-depth collections of CoBrA work in the world, so this is a unique opportunity to reflect on a rarely explored moment in the history of modernism.

Asger Jorn, Underdeveloped Ferocity, 1961, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Leon Anthony Arkus © 2018 Donation Jorn, Silkeborg/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VISDA; Ellsworth Kelly, Two Panels: Green Orange, 1970, partial gift of Charles H. Carpenter, Jr. and partial purchase from The Henry L. Hillman Fund; René Magritte, L’esprit de famille, 1963, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Richard M. Scaife © 2018 C. Herscovici/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

In an episode from the more recent past, one gallery is dedicated to the pivotal decade of the 1980s, when so many artists embraced responsive and politically charged ways of working. Against the backdrop of the culture wars, the photographs of Cindy Sherman and Tseng Kwong Chi speak to artists’ fascination with the fluidity of gender and identity. Artist collectives such as the Guerrilla Girls and General Idea tested the boundaries of art by producing works that resemble activism, even counter-propaganda. Recently acquired photographs by Lorraine O’Grady figure prominently in this gallery as a reminder of how artists, then and now, are demanding that institutions be more open and inclusive.

Other chapters in Crossroads shed new light on familiar movements and mediums, asking, how do artists reinvent traditional mediums and question received notions? One point of focus will consider the minimalist impulse from the 1960s forward. Through artist-centered stories about creative process, the installation will reveal the many ways artists have chosen to distill complex ideas into pared-down forms while responding to nature. For instance, while Ellsworth Kelly’s paintings offer pure shape and color, the artist is a keen observer of the visible world. His abstract shapes may point back to the contour of a snowy hill or a shadow cast by a barn door.

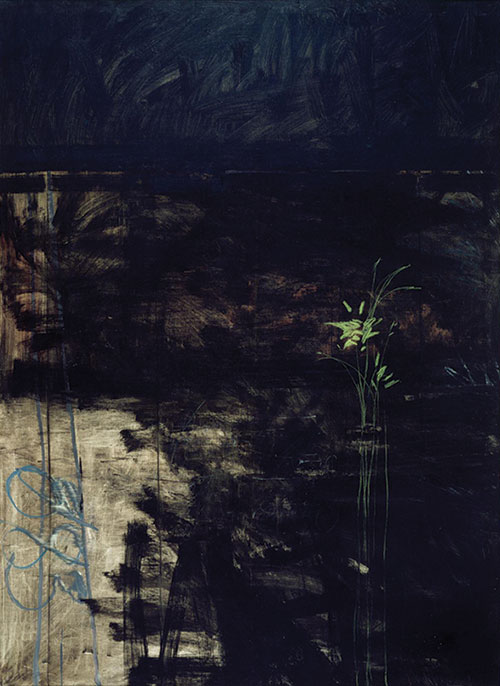

Raymond Jennings Saunders, Night Poetry, 1962, Gift of Leland and Mary Hazard © Raymond Saunders

In similar fashion, an entire gallery will be devoted to the challenges and pitfalls of contemporary painting. Reflecting one of the truly great strengths of our collection, this chapter spans a wide range of approaches and concerns, including the figurative and the abstract, the gestural and the digital. Michael Williams, for example, rejects the blank canvas, instead starting his work on digitally printed grounds that he then embellishes with abstract paint handling. Avery Singer uses the computer modeling environment of Google SketchUp to compose her cyborg-like figures. How does painting remain relevant in our image-saturated culture, and how have artists continued to discover new possibilities for this centuries-old medium?

Another chapter, Night Poetry, dispenses with art history altogether. Borrowing its name from a painting by Pittsburgh-born artist Raymond Saunders, this gallery features works that give shape to artists’ dreams, visions, hallucinations, and nightmares. Of course, the museum’s collection offers history, but it can also be a source of fiction. From the biomorphic abstractions of William Baziotes to the surrealist prints of Hans Bellmer and the secretive installations of Louise Bourgeois, Night Poetry presents an ahistorical grouping of works at the crossroads of day and night, conscious and unconscious.

Finally, in a raucous contemporary gallery, our last chapter looks at artistic agency in the 20th and 21st centuries. How do artists stake out positions? How do they redress historical omissions? How do they locate themselves in a complex and compromised world? It is here that we find a context for our recently acquired Kerry James Marshall painting—an artist who has endeavored to paint the black figure back into a history of art that has marginalized it. In this orbit, we also encounter the strong artistic personas of Isa Genzken and Mike Kelley, both of whom turn mass culture back on itself as a form of critique.

Isa Genzken, Empire/Vampire III, #1, 2004, The Henry L. Hillman Fund, courtesy David Zwirner, New York and Galerie Daniel Bucholz, Cologne

By offering unique and diverse digressions into the museum’s collection, Crossroads reflects our interest in testing out new ideas and mixing up curatorial models in ways that are keyed to our contemporary moment.

Carnegie Museum of Art’s Scaife wing, which opened in 1974, was always intended to house the permanent collection, and it has changed subtly over time, signaling the evolving tastes of curators and audiences. Initially, the galleries offered a long and winding path through time, with pristine white walls and sparsely hung paintings. The 1990s and early 2000s brought architectural interventions and bold wall colors, respectively.

Today, we hope to animate the collection with themes and stories that resonate in the present, offering topical frameworks that blur the distinction between special exhibition and permanent collection. In our current environment of political and social upheaval, 2018 again seems to represent a crossroads. Doesn’t now feel like the right time for a new take?

Receive more stories in your email

Sign upTags:

Art