You May Also Like

Objects of Our Affection: 3D-Printed Prosthetic Hand The STEM of Animation Storytelling through STEMBy day, Nathan Sawaya was a high-powered New York City lawyer, working on mergers and acquisitions and other complex legal issues. In the evenings, he would unwind by drawing, painting, sculpting with clay—and eventually experimenting with Lego bricks, a favorite childhood toy. But what he did with them was hardly child’s play.

With thousands of rectangular bricks, Sawaya sculpted life-size replicas of things inside his apartment —a bowl of fruit, a favorite cartoon character—and posted images of them on a website. Immediately, people contacted him about commissions. He knew he was onto something when the website crashed from too many hits

In 2004, at age 31, he quit his lucrative day job and became a full-time Lego artist, a self-styled career path that drew some eye rolls. A Lego artist? Are you crazy?

The sneers came from some of his former colleagues and the art establishment. Museum directors would laugh, assuming he was making little toy trains and castles. Saddled with steep college debt, Sawaya knew the career change was a risk. Would he be able to pay next month’s rent? Three years later, he was invited to the Lancaster Museum of Art for a solo exhibition. He assumed his first show would also be his last. It turned out to be a huge success.

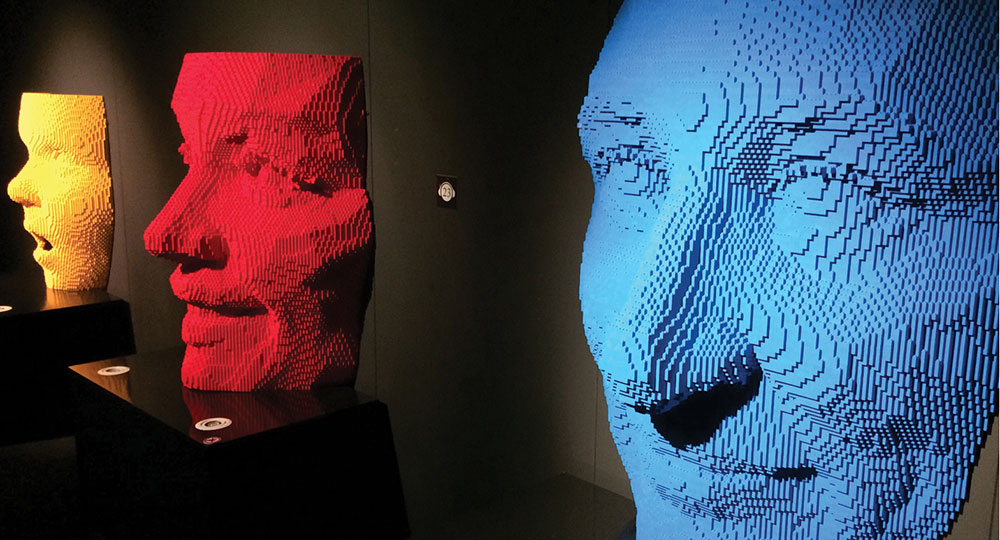

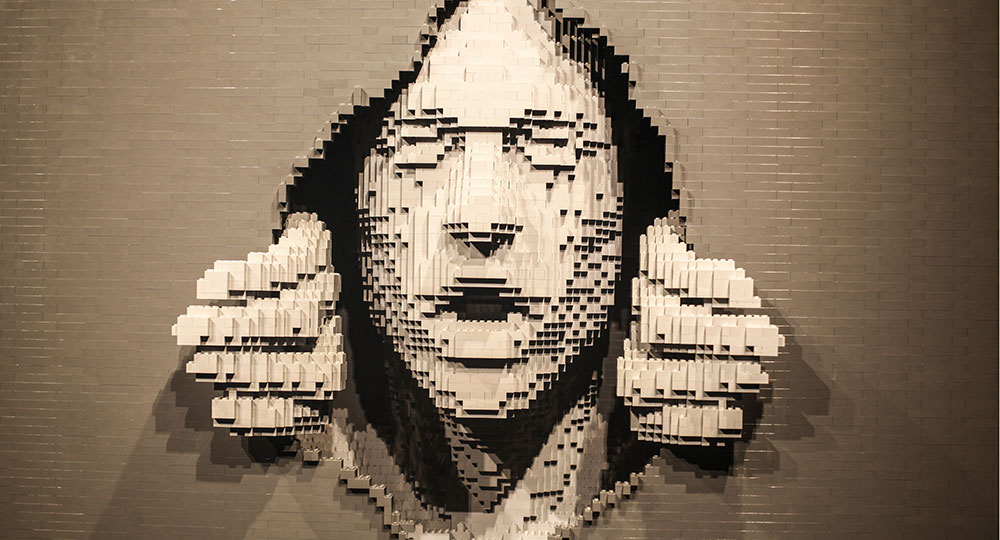

Sawaya has been taking his show, The Art of the Brick, around the world ever since. He’s exhibited on every continent but Antarctica. Now more than 100 large-scale sculptures strong, the blockbuster attraction will soon arrive in Pittsburgh as the first offering in Carnegie Science Center’s new PPG SCIENCE PAVILION™. On view inside the new addition’s 14,000-square-foot Scaife Exhibit Gallery from June 16 through January 7, 2019, The Art of the Brick features some of Sawaya’s most iconic creations, including Yellow, the form of a man from the waist up, tearing open his chest, a pile of Lego bricks pouring out. The sculpture was used by Lady Gaga in the video for her song G.U.Y.

One of Nathan Sawaya’s most iconic creations, Yellow, was used by Lady Gaga in a music video.

The sculpture reflects Sawaya’s need to express himself as an artist with this unconventional material. “This figure is giving it his all,” he says. “His soul is spilling out—the soul is bricks. The kids say, ‘The guts are spilling out.’ The guts are toys they have at home.” Another crowd favorite: Dinosaur, a prehistoric masterpiece sculpted out of 80,020 plastic bricks. To thank the thousands of kids who have come to his shows, Sawaya worked on the 20-foot-long T. rex for three months, painstakingly creating its ribs and vertebrae.

“When you start, you’re so excited,” says Sawaya. “But in the middle [of the process] you question your choices.” Not only did he have to make sure the hulking structure didn’t collapse on itself—the weight of the body, resting on thin legs, also threatened to topple the work. “How do you present it in a way that looks good but is engineeringly sound?” He solved the problem by wiring the beast to the ceiling.

Brick by brick

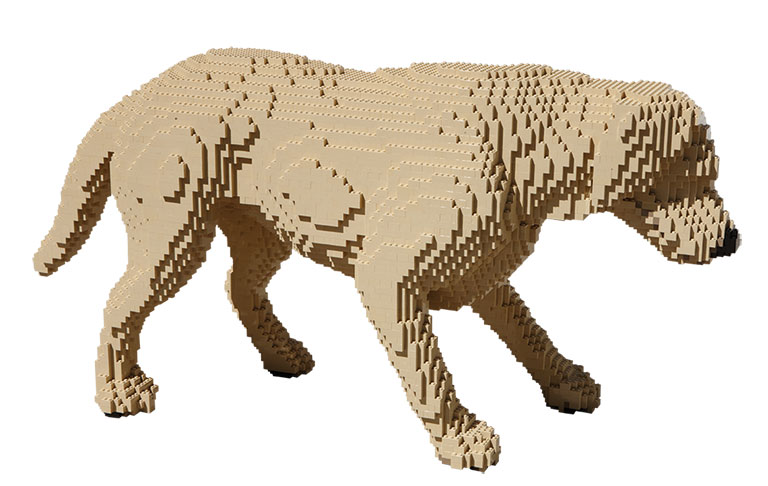

Sawaya always loved Legos. As a kid growing up in Oregon, encouraged by his parents to be creative, he would spread his collection of bricks all over the living room. At age 11, he asked his parents for a dog. When they said no, he built a life-size dog out of Lego bricks —in the process, perfecting the skill of making a curve out of sharp corners. “It’s all about perspective. That is the magic of the brick,” says Sawaya. “Once you learn to build a curve, you can build anything—an egg, a human head.”

When he went off to college at New York University (NYU), he took his childhood Lego bricks along, stashing them under the bed until he had an urge to start building. He always wanted to be in the arts. But when he graduated from NYU, he applied to law school instead. It was the art he did to relax that helped lift him out of depression. “It was a reason for me to get out of bed and do something,” he says. “It really helped me. Art was a way to tell people what I was going through without having to say it.”

When he went off to college at New York University (NYU), he took his childhood Lego bricks along, stashing them under the bed until he had an urge to start building. He always wanted to be in the arts. But when he graduated from NYU, he applied to law school instead. It was the art he did to relax that helped lift him out of depression. “It was a reason for me to get out of bed and do something,” he says. “It really helped me. Art was a way to tell people what I was going through without having to say it.”

His work has appeared at the Clinton Presidential Center and on the White House lawn. Among his inspirations are two public figures who have also forged their own paths: Tom Friedman, the acclaimed sculptor who fashions works from household items such aspirin, sugar cubes, and disposable plastic cups, and skateboarding legend Tony Hawk.

“Tony took something that wasn’t a job and made it a career. Then he made it into an industry. He makes giant leaps. He is not afraid of falling short, or if he is, he does a damn good job of hiding it,” Sawaya has written. “I look at him to see what he’s doing next and say, Should I be doing that? Because for me, he is proof that you can make yourself.”

“It’s all about perspective. That is the magic of the brick. Once you learn to build a curve, you can build anything—an egg, a human head.” – Nathan Sawaya

At any given time, Sawaya works with 7 million Lego bricks. “A lot of people assume I get them for free,” he says. “I buy them like everyone else.” Except, instead of going to the toy store and picking out a box or two, he might shoot an email to The Lego Group to order 10,000 bricks in red or green. Then a truck will show up at one of his two studios, in either New York or California, and deliver Lego bricks by the pallet.

He only works in the traditional shapes and colors, gluing each piece to the structure to avoid mishaps during shipping. “Museums do get grumpy if they open up a crate and see a bunch of loose bricks,” he says. But gluing them means he must use a chisel and hammer to make changes to his sculptures, which always begin with Sawaya putting pencil to Lego graph paper. “You need patience for this job. I have been known to chisel away days’ worth of work.”

Some of the artist’s more personal works are dedicated to the “human condition.” Sawaya works out of a pair of studios in New York and California, and typically has some 7 million bricks at his disposal.

Though he has a staff who helps mount exhibitions and ship the work, “everything you see in the show is made by these hands,” he says. As a result, he sometimes must get injections in his fingers to relieve the pain. “My hands take a beating. It’s an occupational hazard.”

For his efforts, the artist has had little kids ask him for his autographs, and he’s won acclaim from The Lego Group: He was named a Lego Master Builder, a title he earned after making a sphere out of plastic rectangles. The company recently contacted him and bestowed another title on him—Lego Certified Professional.

“I’m told I am the only person who holds both titles. It’s an honor.”

The science of art

Dennis Bateman, senior director of exhibits and experience at the Science Center, says The Art of the Brick is an inspiring example of the enduring relationship between art and science, what today is often referred to as STEAM, or science, technology, engineering, art, and math. “There is a lot of engineering and math and problem-solving that goes into creating art out of 50,000 Lego bricks,” he notes

Sawaya agrees. “Art is not optional,” he stresses, noting that art helps school children score better in science and math, and that he knows from experience that art can also boost self-confidence and help to combat depression. “Art in your life makes you a happier person. When I was a lawyer, I wasn’t happy. Creating art made me happy.”

“There is a lot of engineering and math and problem-solving that goes into creating art out of 50,000 Lego bricks.” – Dennis Bateman, senior director of exhibits and experience at Carnegie Science Center

His hope is that an exhibition like The Art of the Brick will invite more people into museums, the art world, the creative spaces in their own brains. “It democratized the art world,” says Sawaya. “I’ve met people at my exhibit who have never been to an art gallery before.”

The Art of the Brick also uses the famous toy that turns 60 this year to introduce museumgoers (and non-museumgoers) to a famous collection of masterpieces. In the section titled Art History, visitors can get an up-close view of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, Johannes Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring, and Michelangelo’s David—all rendered in Lego bricks.

Before replicating iconic masterpieces, Sawaya researched the works and viewed many of the originals.

Sawaya researched each of the 50 iconic works extensively and has seen some of the originals hanging on museum walls. He hopes to eventually see them all. “How do you talk to a 5-year-old about the Mona Lisa?” he asks. “Here it is—a gateway to the art world.”

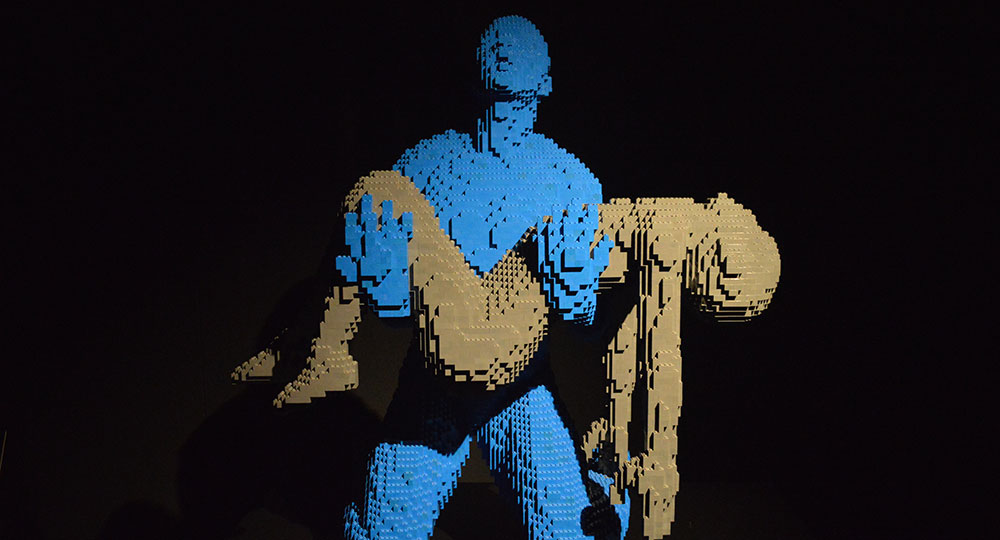

Many of his sculptures are of the human form, including Swimmer, a female figure captured in mid-stroke in choppy waters, all sculpted from bricks of the same blue color. She looks strong, indefatigable. Visitors see different messages in the popular sculpture —swimming upstream, swimming among sharks. In Disintegration, a man standing against an orange wall sheds bricks from his body, a study of angst.

The author of two books, Sawaya features in Writer a man pushing a pencil as large as he is. A piece titled Everlasting shows an elderly man and woman holding hands, steadying each other. He was inspired to make this work after he saw such a couple on the sidewalk in Manhattan, devoted to each other as the fast-paced world swept by.

As he does in each host city of The Art of the Brick, Sawaya plans to unveil a new, site-specific sculpture at the exhibition’s June 16 opening. He won’t give any clues, except that it isn’t based on bridges, sports, or food. So Pittsburghers can cross a Lego-inspired Heinz ketchup bottle or a rippling Terrible Towel off the list of possibilities.

Those who come to see Sawaya’s impressive sculptures can look but not touch. So in a nod to the Science Center’s interactive nature, its team is developing a hands-on companion space dubbed Science of the Brick where visitors can satisfy their tinkering urges. One station will encourage builders to use Lego bricks to erect replicas of famous architectural structures around the world. Another will prompt them to assemble using only the sense of touch—a blind build. When the show departs Pittsburgh, the interactive component will travel with it.

Another add-on experience titled What is Art?, designed by the Science Center in partnership with educators from sibling museums The Andy Warhol Museum and Carnegie Museum of Art, explores the intersection between pop culture and fine art. If a Campbell’s soup can is art, why not Lego sculptures?

“How do you talk to a 5-year-old about the Mona Lisa? Here it is—a gateway to the art world.” – Nathan Sawaya

Despite showing his sculptures in museums around the world, Sawaya still faces some skeptics. “It is what it is,” he says. “I’ve had some great reviews. Other art critics view it as a toy. At least they’re taking it seriously enough to show up.” Sawaya is by no means alone, though. Chinese activist-artist Ai Weiwei, who exhibited work at The Warhol and the Museum of Art last year, recently created portraits of 176 political activists using 1.2 million Legos (two years after the artist had a public rift with the Danish toy company, which refused to send him the bricks in bulk). Inspired by his then 5-year-old son, Ai chose Legos as a disarmingly playful and ubiquitous material that can easily be constructed, or deconstructed, on a massive scale—in some ways acting as a metaphor for freedom.

“The Art of the Brick introduces students to art in a language they understand,” says Paul O’Brien, artist-educator and studio programs manager at The Andy Warhol Museum. “At The Warhol, students see Warhol’s silkscreens on the walls. It’s once they get into the studio and try silkscreening themselves that they really understand the process. With The Art of the Brick, they already understand the process—everyone has snapped Legos together. It’s a wonderful way to get them to look at art in a different way and have conversations about what is art and who makes it.”

The Art of the Brick

Major sponsors of The Art of the Brick include Arch Masonry, Baierl Toyota and Baierl Subaru, Citizens Bank, and Isaly’s

Renderings of the new PPG Science Pavilion, including PointView Hall’s outdoor terrace, by Indovina Associates Architects.

Carnegie Science Center: The Future is Now

On June 15 and 16, an expanded Carnegie Science Center will open its new PPG SCIENCE PAVILION™ by—how else?—inviting the community in. The 48,000-square-foot addition is the centerpiece of the SPARK! Campaign, which raised $46 million to build the pavilion, refresh existing exhibitions, create the bigger-bolder-better Rangos Giant Cinema, and expand the Science Center’s science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) programming, which already reaches tens of thousands of schoolkids each year.

On Friday evening, June 15, a community celebration will be the first official invitation-only event to occupy the new pavilion’s PointView Hall, a 9,800-square-foot, multipurpose meeting space that will be used by the Science Center for its STEM competitions and other events, and rented out for private events and conferences. The hall’s 1,600-square-foot terrace takes full advantage of the pavilion’s spectacular view of Downtown and the Point. (If you’ve never watched Fourth of July fireworks from the Science Center, this might be the year to do it!)

On Saturday, June 16, Carnegie Museums members are invited to their own celebration in PointView Hall from 11 a.m.–5 p.m., and 1,000 lucky members will be the first to see The Art of the Brick. This inspiring, internationally touring exhibition is the first of many blockbuster shows that will come to Pittsburgh now that there’s a venue that can host them: the pavilion’s Scaife Exhibit Gallery, a two-level, 14,000-square-foot space, can house one large exhibition or two smaller-sized shows.

On the ground floor of the new Science Pavilion, nine FedEx STEM Learning Labs will serve as a testament to the Science Center’s core mission of STEM learning and career development. The 6,000 square feet of specialized classroom and lab spaces will host all kinds of inquiry-based learning, including summer camps that explore DNA extraction and replication, crime-scene analysis, and environmental testing. The Science Center already welcomes more than 4,700 kids to its on-site classes and summer camps each year, and the new learning labs will increase the capacity for these programs by 40 percent.

All told, the Science Center expects its annual attendance of nearly half a million people to increase as much as 50 percent thanks to the new experiences made possible within the PPG Science Pavilion. More hands-on learning, more science-related fun for all ages, and an even larger, more beautiful footprint of regional impact along Pittsburgh’s burgeoning North Shore.

Receive more stories in your email

Sign up