On Monday, August 21, at 2:35 p.m., a shadow will fall across Pittsburgh—an event that may reveal hidden secrets of the sun, and, at the very least, provide an excuse for a stellar summer celebration.

As the moon covers the face of the sun, a total solar eclipse will drape a black sash from Oregon to South Carolina. The 70-mile-wide path of total darkness will skirt Pittsburgh, where the moon will block only 80 percent of the sun. But the three minutes of twilight that we will experience marks an epic astronomical event: the first total solar eclipse over North America in 38 years, and the first to be seen solely from the continental United States since—wait for it—1776.

If that historic coincidence provokes goosebumps, it’s only human. Eclipses have long been associated with cataclysmic events, including the crucifixion of Jesus and the birth of Mohammed. “We know it’s science. But to people who lived hundreds of years ago, anything that wasn’t normal in the sky was an omen,” says Dan Malerbo, education and program development coordinator for Carnegie Science Center’s Buhl Planetarium.

This summer, the rare eclipse’s timing and path are more auspicious. Carnegie Science Center plans to throw the city’s best viewing party beginning at 1:10 p.m., as the moon slowly edges across the sun, with maximum views at 2:35 p.m. and full sunshine returning by 3:55 p.m.

“It will be pretty spectacular,” says Mike Hennessy, Buhl Planetarium and digital media manager at the Science Center. “We’ll see the moon coming from the right-hand side in front of our friendly neighborhood star, exiting stage left.”

“ Moments before totality a wall of darkness comes creeping towards you at speeds of up to 5,000 miles per hour—this is the shadow of the Moon. You feel alive. You feel in awe. You feel a primitive fear. Then—totality. In this moment there is just you and the Universe.” – Kate Russo, author, Being in the Shadow

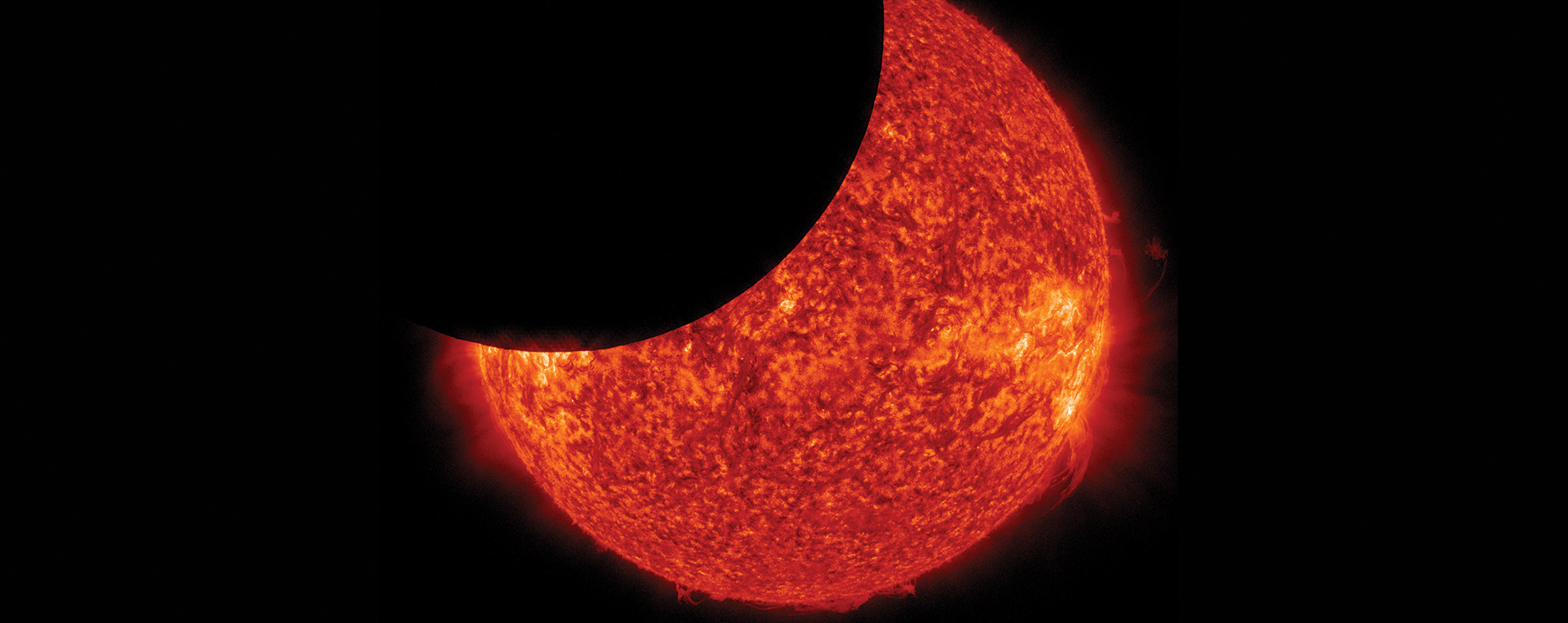

Assuming the weather cooperates, Hennessy promises a “high-energy outdoor viewing party,” complete with take-home solar-viewing glasses, solar telescopes, and roving interactive demonstrations. Solar-viewing telescopes will be equipped with hydrogen alpha filters, which expose deep red wavelengths that reveal active sunspots and solar prominences—bright, gaseous loops that curl from the sun’s surface. “They allow visitors to see just how dynamic the sun is,” he says.

Most younger Americans like Hennessy, age 40, have never witnessed a solar eclipse. Since 1960, just three such events have been visible from the United States mainland—in 1963, 1970, and 1979. The moon’s orbit around Earth tilts at a stubborn five-degree difference from Earth’s orbit around the sun. As a result, the moon’s shadow usually misses Earth, passing above or below our planet at the new moon.

This time, weather permitting, the United States is in prime viewing position. Over half of all Americans live within a day’s drive of this year’s path of totality. Combine that proximity with a date at the height of the summer vacation season, and it’s easy to see why August 21 is being branded as the Great American Eclipse. Both professional and amateur eclipse chasers are packing for the ultimate astronomic road trip.

Fred Espenak, one of the nation’s foremost eclipse scientists, has spent the past four decades observing the phenomena on all seven continents. Known as Mr. Eclipse, he’s never lost his awe for the experience. “You can read dry facts and understand the mechanics,” he says, “but then you see the dynamic range of brightness and the gossamer texture of the corona [the halo of blazing plasma that encircles the sun]. When you’re plunged into darkness, it hits you at an internal level that you are not anticipating. The hair on your arms and neck stands up.”

On August 21, he plans to be under dark skies in rural Wyoming. Like Espenak, Pittsburgh astronomers plan to be smack in the path of totality. Malerbo says he’ll head to Nashville, a base that will allow him to drive in any direction to avoid last-minute cloudy weather. Kathy DeSantis, vice president of the Amateur Astronomers Association of Pittsburgh (AAAP), will travel to Louisville, Kentucky, with the same strategy. Her fellow AAAP member Becky Valentine will camp out at the spot most observers think will provide the ideal viewpoint: rural Madras, Oregon. And Pittsburghers vacationing at Hilton Head, South Carolina, will be among the last to see the eclipse (although not in totality) before it vanishes over the Atlantic.

Scientists gain a wealth of cosmic data from every solar eclipse. A French astronomer noticed an odd yellow line in the sun’s spectrum during an 1868 event; he’d discovered helium, the second most abundant element in the universe. During a total solar eclipse in 1919, Arthur Eddington validated Einstein’s general theory of relativity.

Astronomers hope that the August 21 findings will provide clues to the physics of the corona, where temperatures actually exceed the 6,000-degree Celsius surface of the sun.

“As you move out into the corona, it gets hotter—to three million degrees in some parts,” says Espenak. “It’s still a major question: What is the mechanism that heats the corona? As a near-vacuum, it doesn’t contain a lot of energy. There are probably a half-dozen theories on what is actually happening.”

In the run-up to the big day, the Science Center will offer sun-themed programming for all ages. On “Solar Sundays” the Buhl Planetarium will screen Solar Quest, a dramatic introduction to the astrophysics of the sun. Before daily star shows, guests will be treated to a simulated trip around planet Earth, chasing the path of the eclipse across the country. And on the day itself, the planetarium will livestream NASA’s entire eclipse broadcast on its Sky-Skan 4K projection system—a useful Plan B if clouds obscure outside viewing.

For those who will miss the August 21 event, don’t despair. Instead, mark your calendar for April 8, 2024, when the shadow of the next partial solar eclipse will pass over western Pennsylvania.

Receive more stories in your email

Sign upTags:

Science & Nature