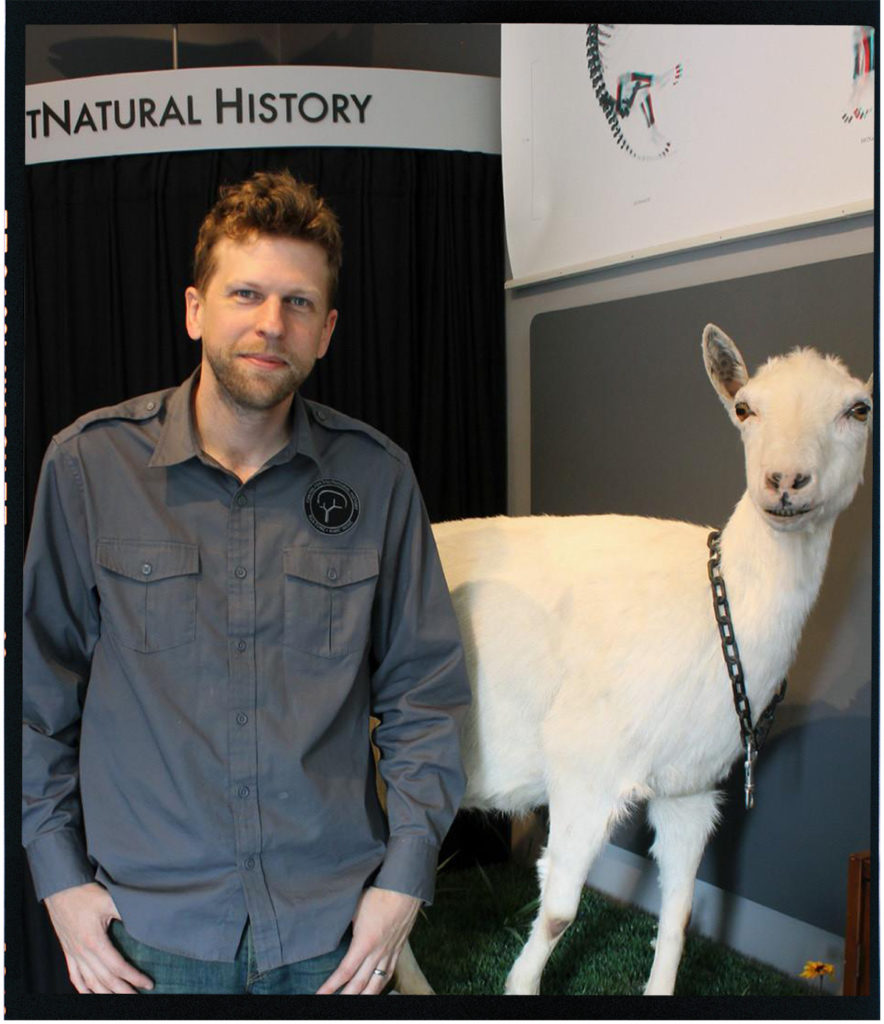

Richard Pell is an unlikely person to start a new scientific museum, especially one receiving international acclaim. He is, after all, an artist who never took a science course after high school. Yet, inside a small storefront on Penn Avenue in Garfield, he’s exhibiting the kind of plants and animals not found in any conventional museum: a ribless laboratory mouse embryo and the stuffed remains of Freckles, a goat that produced spider silk in its milk. As founder of the Center for PostNatural History, Pell collects and interprets organisms that have been intentionally modified by humans through selective breeding and genetic engineering. Currently an assistant professor of electronic media at Carnegie Mellon University (CMU), Pell has always experimented with art and technology. As an art major at CMU, he was a founding member of The Institute for Applied Autonomy, a collective of engineers, artists, and activists that created TXTmob, a predecessor to Twitter that let users share mobile phone SMS text messages, and robots that write graffiti. But his interest in science deepened in 2004 upon attending his 10th high school reunion, where he told a classmate about his robots. The classmate replied, “I guess I make robots, too, but mine are alive, and I program them with DNA.” He invited Pell to join him in San Francisco at one of the earliest conferences on synthetic biology. Pell was hooked. He pored over textbooks on molecular biology. And when he couldn’t find genetically-altered specimens in natural history museums, he opened his own museum in 2008. Today, the Delaware native has earned the respect of the PhDs at Carnegie Museum of Natural History, and he and his art students are collaborating with them on a new exhibit exploring the Anthropocene, or Earth in the age of humans.

Your museum displays dogs. What’s their significance?

Post-natural history begins with the domestication of the dog. Dogs are the first species of plant or animal to be reproductively altered by people. We began to co-evolve with one another a bit more than 10,000 years ago. We were hunting partners, and we started to change each other. We changed their habitat. We changed the adaptations needed to get along. Dogs and humans have communication between them that dogs don’t have amongst each other.

What do people expect when they walk through the museum’s door?

The first thing they often think about are things they’ve read about in the news—our goat that made spider silk in her milk, for instance. And they think about it as this really exotic thing, a bit frightening, something science fictional. What they don’t consider is that every vegetable they’ve ever eaten has also been radically altered by human intervention, that almost every pet they’ve ever owned has been radically changed.

What is your prize possession?

When I first opened the museum, I was interviewed by Nature magazine, and they asked me what my Holy Grail specimen would be. I said, ‘a BioSteel™ goat, of course,’ and a couple weeks later, I get a call from researcher Randy Lewis. He said, ‘Hey, I’m the goat guy. I’ve got the goats.’ I said, ‘That’s great. So, what would we have to do in order to preserve a specimen?’ And he said, ‘Well, you know, eventually, we’re going to have to put one of them down.’ And about nine months later, I was contacted again, and I had a very short period of time to find a taxidermist in Logan, Utah, who was willing to do the work. But I managed to find one. It’s one of several species of goats, sheep, and cattle that are engineered to produce pharmaceuticals and other materials in their milk, and it’s the only one on public display in the world.

Do your visitors come away with a value judgment on genetically modified organisms?

Whatever that judgment is, it’s their own to make. We try very hard not to hand one out. I would be lying if I told you that my interest in this stuff didn’t come from a place of anxiety and dread. Over time, I learned that my own instincts about what was worrisome maybe weren’t super reliable, that the more I learned, things that seemed worrisome on the surface maybe were less so. That’s not to say that there aren’t issues that are of concern. One that comes up frequently is antibiotic resistance, the overuse of this small set of tools that we have. And that plays out in so many ways

in biotechnology.

Why don’t natural history museums display these specimens?

There’s a tendency to try to edit people out of the equation. In dioramas, you never see a building in the background, or a smokestack, or an airplane flying by. We’ve removed human culture in favor of this idealized notion of nature without people. We not only miss out on all this other stuff, but we miss out on the responsibility we have for the world.

Is your relationship with Carnegie Museum of Natural History changing that?

The opportunity for us to have a peer relationship is really exciting. I would love to bring artifacts from the Carnegie over here, and I hope to bring specimens from our collection over there. There’s a good chance that Freckles is going to take a walk to the Carnegie.

Receive more stories in your email

Sign up