It was in the trenches of World War I that Horace Pippin discovered he was an artist. The 29-year-old laborer from West Chester, Pennsylvania, had enlisted at the beginning of the war, eventually becoming a member of the legendary black regiment known as the Harlem Hellfighters. He passed the time between firefights illustrating his journals. In an undated letter now archived at the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art, he wrote that the war “brought out all the art in me.”

A German sniper shot Pippin through his right shoulder—his painting arm. No longer able to lift his arm above his shoulder, he worked by propping his right wrist on his left wrist for support. His rugged paintings communicate a distinct vision of American life, with vivid scenes of his community and dramatic depictions of radical abolitionist John Brown and President Abraham Lincoln.

Despite receiving no formal arts training, Pippin enjoyed artistic success during his lifetime, appearing in group shows at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the National Gallery in Washington, D.C. Over his career, he produced about 140 images—one of which has hung in Carnegie Museum of Art for much of the last 30 years. Abe Lincoln’s First Book, painted two years before the artist died in 1946, depicts an imagined scene of young Lincoln in a dark room illuminated by a single candle as he reaches into the blackness for a book.

Horace Pippin, Abe Lincoln’s First Book, 1944, Carnegie Museum of Art, Gift of Sara M. Winokur and James L. Winokur

Eric Crosby, Carnegie Museum of Art’s Richard Armstrong Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art, sees in the painting “the desire to reach out for knowledge even when it’s shrouded in darkness.”

That work became a “guiding spirit” for Crosby and co-curator Amanda Hunt as the pair selected works for 20/20: The Studio Museum in Harlem and Carnegie Museum of Art, an exhibition that paints a metaphorical picture of America by focusing on artists across disciplines who address themes of race, national identity, socioeconomics, and social justice. It will be on view at the Museum of Art from July 22 through December 31.

The unique collaboration features the work of 20 artists from each institution’s collections, the majority of whom are people of color. While museums often lend works to one another for special exhibitions, it’s rare to have disparate collections in dialogue with one another.

The show unfolded as “a natural, political conversation between Eric and I last March,” says Hunt, associate curator at The Studio Museum at the time, and now director of education and public programs at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. “We felt it was urgent to find a way to describe visually the post-Obama moment that was looming on the horizon.”

20/20 not only refers to the number of artists in the show, she notes, but also evokes the past—as in the expression “hindsight is 20/20”—and looks to the future to the year of the next presidential election and beyond.

Noah Davis, Black Wall Street, 2008, The Studio Museum in Harlem, Gift of David Hoberman Noah Davis reimagines the deadly Tulsa race riot of 1921. The Greenwood neighborhood where the violence occurred was known as Black Wall Street due to its thriving business district.

At the Museum of Art, we often approach our collections with a historical lens, because it’s important to relay the role of art in human history for our visitors,” says Crosby. “It is equally critical to surface our collection for the present because objects from the past can always help illuminate our contemporary moment. I’ve always admired The Studio Museum in Harlem for its curators’ ability to foreground the social and political relevance of the museum’s collection consistently through their work.”

The exhibition provides a fresh venue for The Studio Museum, as it prepares to undergo a major expansion. Known inter-nationally for the catalytic role it plays in promoting the work of artists of African descent, the museum houses about 2,200 works of art. For Carnegie Museum of Art, 20/20 presents an opportu- nity to tease out the contemporary relevance of potent images such as Abe Lincoln’s First Book, the earliest work in the exhibition.

“We felt it was urgent to find a way to describe visually the post-Obama moment that was looming on the horizon.

– AMANDA HUNT, CO-CURATOR OF 20/20: THE STUDIO MUSEUM IN HARLEM AND CARNEGIE MUSEUM OF ART

A LIGHT IN THE DARKNESS

The show is divided into six groupings: A More Perfect Union; Working Thought; American Landscape; Documenting Black Life; Shrine for the Spirit; and Forms of Resistance.

“It’s about creating a space so that visitors can make their own connections,” says Crosby. “We’re providing a loose guide to thinking and reflecting on some of these issues—on American values,” adds Hunt. “We are telling our version of what the country looks like to us in this current moment, and how we could shape a larger narrative between these two collections to think about this context of America.”

Pippin’s painting stands on its own to begin the exhibition, followed by the section “A More Perfect Union,” which includes artworks that grapple with the gap between America’s democratic ideals and the reality of economic inequality. “Striving towards ‘a more perfect union’ is a phrase in our country’s founding document, but it’s not one that is resolved,” Hunt says. “It is something that we are continuously striving for. It’s always shifting, and that’s not because of whatever political regime is in power. I think this is something that America is always contending with or responding to as the world changes.”

This theme is echoed in works such as Gordon Parks’ Emerging Man, Harlem, NY. To Hunt, the black-and-white photograph made for Life magazine in 1952 to illustrate a scene from Ralph Ellison’s novel The Invisible Man is “pure poetry.” It shows a man peeking out of a man- hole. “It’s about an emergence from a dark period and seeking light,” Hunt says. “This seeking is mapped onto our politics.”

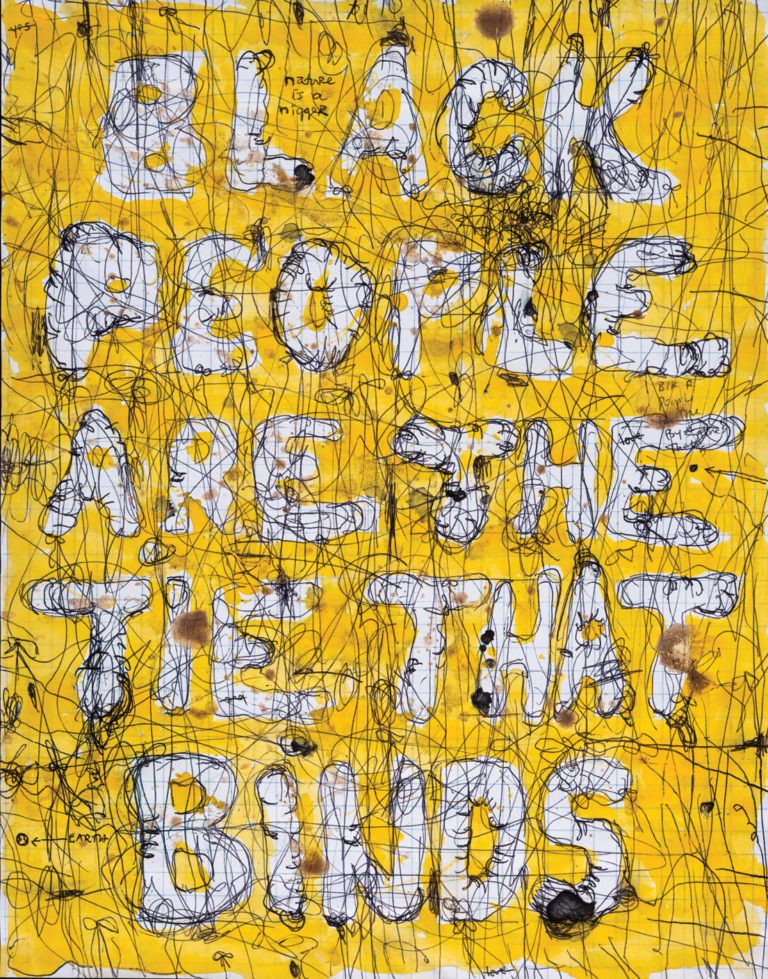

Other works in this section include Jasper Johns’ 1973 screen print of the American flag, which he’s doubled and turned on its side, ren- dering it abstract and “showing just how many colors lie beneath the iconic symbol” says Crosby; Louise Nevelson’s Homage to Martin Luther King, Jr., an eight-foot-tall abstract wall sculpture made of found materials; and works from a series of Skin Set Drawings by multidis- ciplinary artist Pope.L that confront the absurdities of language used to describe and categorize color, including Black People are the Window and the Breaking of the Window.

Pope.L, Black People Are the Tie That Binds, 2004-2005, The Studio Museum in Harlem, Gift of Martin and Rebecca Eisenberg, Scarsdale, New York

WORKING THOUGHT

Retired educator Nancy Washington, along with her husband Milton, who passed away last year, has been involved with the Museum of Art for decades. In 1994, the couple started a fund to help the museum purchase works by artists of the African diaspora. “All members of a community desire to see themselves reflected in art as proof that they actually exist,” says Washington, who also lent the museum a Melvin Edwards sculpture from the pair’s personal collection for inclusion in 20/20.

Lo (for Locardia Ndandarika), a 1997 work by Edwards named for an important Zimbabwean sculptor, is part of a series called Lynch Fragments. In it, Edwards makes tactile abstract sculptures by welding together found materials like machine parts, tools, and chains. “The chains incorporated into Lo suggest the chains of slavery,” Washington says. “The sculpture evokes the still-not-fully-understood American story of centuries of free labor and its impact on our present-day society and economy.”

“It can be argued that our country has been seen most accurately by those it has cast as ‘outsiders.’”

– NANCY WASHINGTON, ART COLLECTOR AND MUSEUM SUPPORTER

The sculpture is paired with other works from the series, Working Thought and Cotton Hangup, both part of The Studio Museum’s collection. Motivated by Edwards’ engagement with the theme of labor and exploitation, the curators chose “Working Thought” as one of the show’s thematic groupings to connect Edwards’ references to slavery with works that address contemporary concerns, such as David Hammons’ sculpture Untitled. Made in the year 2000, it consists of 30 cardboard boxes stamped “Made in the People’s Republic of Harlem” and wrapped in plastic wrap on top of a moving pallet. The conceptual nature of the work captivates Christel Temple, chair of the Africana Studies Department at the University of Pittsburgh, who this past spring gave a four-part lecture series for Museum of Art docents centered on black history and culture.

“I was amazed by how art can be so simple, yet signify such great meaning,” she says. To her, the piece evokes the Harlem Renaissance as well as cur- rent controversies about the gentrification of the neighborhood. “Harlem is such an American story,” says Temple. “And Hammons’ piece calls to mind all of that. I had to chuckle. So simple and yet so profound.”

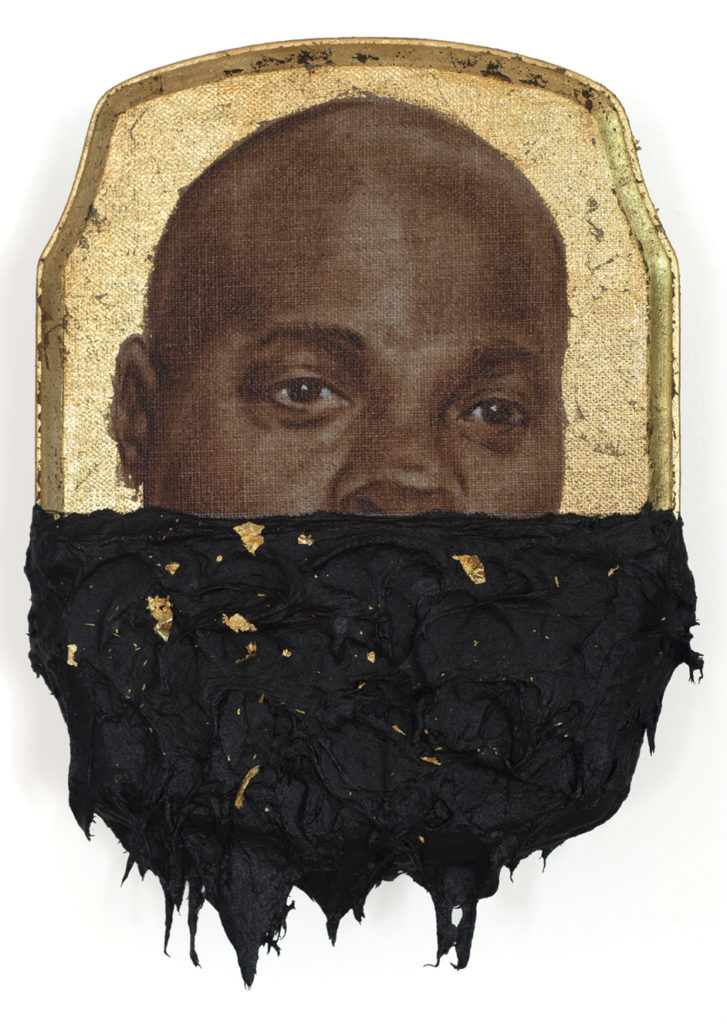

Titus Kaphar, Jerome IV, 2014, The Studio Museum in Harlem, Gift of Jack Shainman Gallery

While searching for his father’s prison records, Titus Kaphar found images of 99 other black, incarcerated men who shared his father’s name, sparking a series of oil portraits based on their mug shots. The height of tar used to cover the images reflects the amount of time served.

INSERTING BLACKNESS

Contemporary art is always going to be “elliptical, or not necessarily tied down to any one theme,” Crosby says. That’s why in the “American Landscape” section viewers will find photography as well as a text-based work by Jenny Holzer that indirectly references landscape; and why the “Shrine for the Spirit” grouping is populated by abstract sculptures that gesture to quiet reflection and the more spiritual practices of artists.

One part of the show, however, sets abstraction firmly aside. “Documenting Black Life,” which features works by two black photographers, is described by Crosby as “an exhibition within an exhibition” that provides a rarely pictured version of America and Americana.

Charles “Teenie” Harris was a photographer for the black newspaper the Pittsburgh Courier from 1934 to 1975, amassing the largest photographic archive documenting an urban black community. His archive of nearly 80,000 images was acquired by Carnegie Museum of Art in 2001. In 20/20, Harris’ work is paired with one of the leading figures of the Harlem Renaissance, James VanDerZee, who was known for his studio portraits of Harlemites taken during the 1920s and 1930s, and whose archive The Studio Museum stewards.

“We wanted to set up a dialogue between two artists who created such indelible photographic archives of black life in these two cities,” Crosby says. “Their archives are essential to our respective collections,” adds Hunt, “so it’s really special to be able to have them in conversation with each other.”

LaToya Ruby Frazier, Momme, 2008, Carnegie Museum of Art, Second Century Acquisition Fund, Courtesy of the artist and Michel Rein, Paris/Brussels

The idea of documenting social inequality and historical change is also central to the work of photographer and Braddock, Pennsylvania, native LaToya Ruby Frazier. Frazier blends autobiography and documentary in photographs grounded in the crumbling landscape of her hometown, a once-thriving steel town. Her black-and-white portraits of her mother, grandmother, and herself underscore the connection between the town’s eco- nomic collapse and the consequences of neglect for her family and the borough’s historically marginalized working-class, black community.

“Her work is consistently eye-opening and uncompromising,” Crosby says. “She maps a landscape that is simultaneously familiar and strange, documenting the very real effects of industry on the American landscape. She also brings that desire to document inside and explores the internal dynamics of her family.”

Crosby views 20/20 as an opportunity to shed new light on the Museum of Art’s collection. He acknowledges that, like any museum collection begun more than 120 years ago, it has gaps. But for him 20/20 is about bringing greater prominence to its lesser-known stories and voices, including artists of color.

As Nancy Washington puts it, in this telling of America as it has been shaped by matters of race, justice, and freedom, “It can be argued that our country has been seen most accurately by those it has cast as ‘outsiders.’”

The Museum of Art is partnering with local nonprofits to engage audiences in the ideas explored in 20/20, particularly the role of art at times of social and political change. By Any Means—a project of Pittsburgh-based art historian and writer Kilolo Luckett, who creates art experiences in Pittsburgh related to black contemporary art—will host a series of gallery conversations led by artists, collectors, and scholars. The museum will also commission writers from the literary organization City of Asylum, which offers refuge to writers in exile, to create work in response to art in the exhibition.

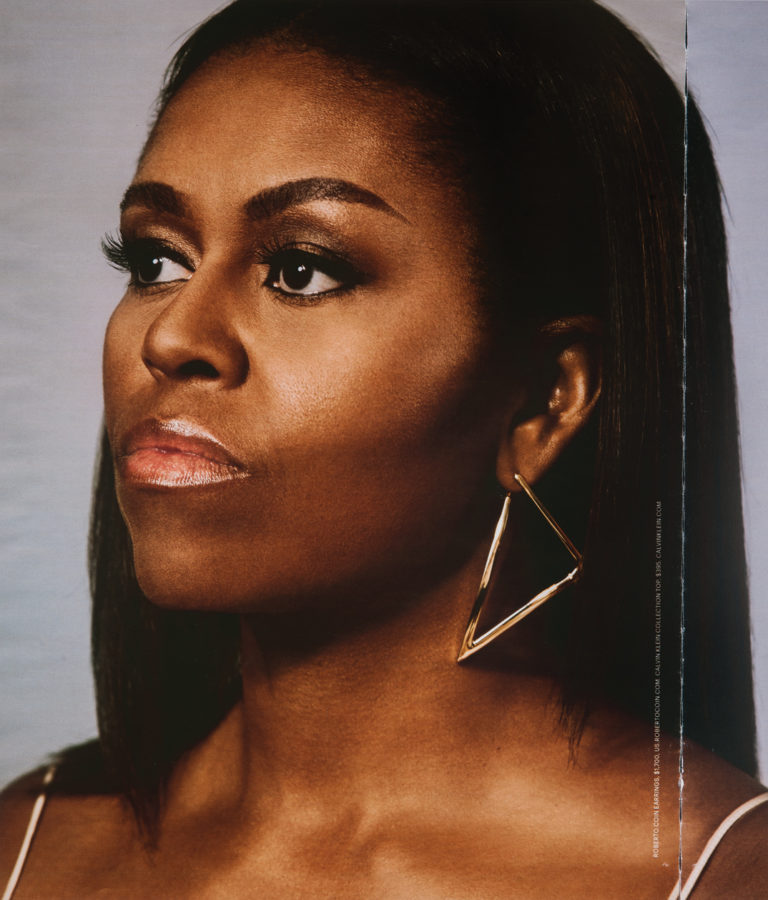

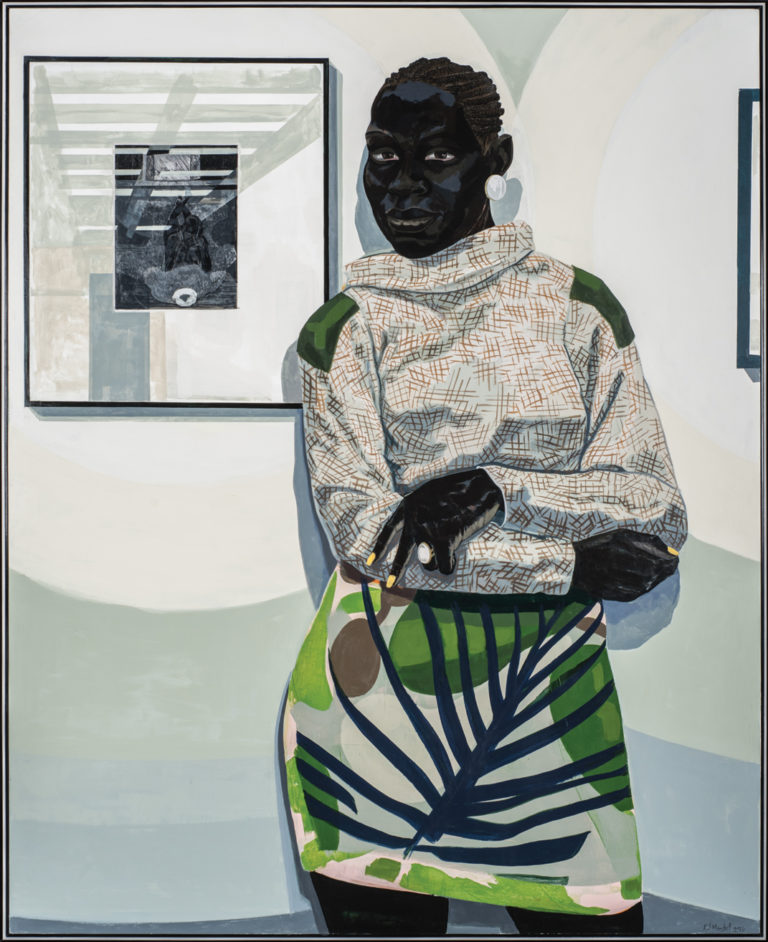

Two recent Museum of Art acquisitions that speak to the museum’s ongoing commitment to collect and exhibit more female artists and artists of color will make their debut within the show’s “Forms of Resistance” grouping: Collier Schorr’s photograph The First Lady (Diplomat’s Room, Rihanna, 20 Minutes), a portrait of Michelle Obama that originally appeared in the New York Times Magazine and was re-photographed from the publication’s tear sheet, in essence locking the iconic figure in an editorial space; and Kerry James Marshall’s Untitled (Gallery), a painting of a black woman standing against the white walls of a gallery.

Collier Schorr, The First Lady (Diplomat’s Room, Rihanna, 20 Minutes), 2016, The William T. Hillman Fund for Photography © Collier Schorr

Kerry James Marshall, Untitled (Gallery), 2016, Carnegie Museum of Art, The Henry L. Hillman Fund © Kerry James Marshall, Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner, London

“The pieces in this section speak to the many ways in which contemporary artists are inserting notions of blackness and black identity into traditionally white spaces,” Crosby says. “Whether it be the white walls of the gallery, the white page of mass editorial media, or the White House itself.” Crosby adds, “Marshall in particular is an artist who has shaped his entire career as a painter around the aspiration to emphatically insert the black figure and black culture into the Western canon of painting in which that figure has been marginalized, silenced, or erased.”

This impulse harkens back to the painting by Pippin, an artist who “very much painted his values,” says Crosby, noting Pippin asserted his own vision of American identity in his paintings of Lincoln and other historical figures.

These two works—one from 2016 and one from 1944—loosely bookend the exhibition and speak to the ways in which American national identity and notions of democracy have changed over time, inching toward greater inclusion. But as is evident in the artwork, it’s an American landscape still marred by economic inequality and racial disparities.

How—and if—art museums should respond to these shifts and other political upheavals are questions at the heart of 20/20.

“Do we want our museum to be a standardized textbook for art history, or do we want our museum to be a forum for art and ideas that are rele- vant to our contemporary moment?” asks Crosby. “That’s a legitimate question, and we should ask it with our audiences.”

Major funding for 20/20: The Studio Museum in Harlem and Carnegie Museum of Art is provided by The Henry L. Hillman Fund. Additional support is provided by The Heinz Endowments, The Fellows of Carnegie Museum of Art, and The Ruth Levine Memorial Fund.

Receive more stories in your email

Sign up