In Jaune Quick-to-See Smith’s 2018 painting Trade Canoe: The Surrounded, a craggy-faced settler complete with pilgrim hat and drooping mustache perches on one end of a canoe, dwarfing a row of seven figures in braids clustered at the other end. A member of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Indian Nation, the artist is known for layering iconic imagery, often taken from art history, into her vibrant and dense compositions.

The three-panel work, part of a series on the mass dispossession and oppression of Native peoples, stretches 14 feet long—with a center panel that towers above the two side panels to accommodate a looming pile of goods weighing down the canoe. A dialogue balloon reading “Hope, sweet hope” drifts over the figures. It’s a puzzling phrase. Do the goods represent hope? Or, given the devastating effects of colonialism on Indigenous nations, does the word “hope” point to the false hope of broken treaty after broken treaty, or the lure of commodities that pulled settlers ever farther into Native American land?

“I just love the potency of Smith’s work. Her paintings question the stories we tell ourselves about the origination of our nation,” says Eric Crosby, the Henry J. Heinz II Director of Carnegie Museum of Art. As if taking a cue from Smith, Crosby took on reconsidering the museum’s own origins while curating Working Thought, an exhibition that puts a spotlight on 35 artists whose works grapple with notions of labor, class, and economic inequity through a range of mediums and artistic practices. Running March 5 through June 26, with some portions continuing to the end of July, the expansive show will occupy the Heinz and Forum galleries and a part of the Scaife galleries. Rather than an opening night, the museum will host a week of celebratory activities leading up to May 1, International Workers’ Day.

“The relationship between art, economy, and labor hasn’t been fully explored at this particular museum, which has as its historical context the rise of industry in Pittsburgh,” Crosby asserts.

“This exhibition is about bringing people closer to the riskiness of art and to the multifaceted roles of artists in our society and the positions they take.”

-Eric Crosby, The Henry J. Heinz II Director of Carnegie Museum of Art and Curator of Working Thought

He started thinking about the exhibition in 2017 while collaborating with Amanda Hunt, then associate curator at the Studio Museum in Harlem, on 20/20: The Studio Museum in Harlem and Carnegie Museum of Art, an exhibition that featured works from both institutions’ collections. One piece stuck with Crosby: Working Thought, a sculpture of welded steel by Melvin Edwards. Part of the “Lynch Fragments” series, the sculpture fuses found objects—including railroad spikes and chains—to evoke a connection between racial violence and exploitative labor. Though the Edwards piece isn’t included in Working Thought, Crosby retained the title.

“It’s a vernacular phrase,” he explains, “for something that you are still chewing on or mulling over, something that isn’t quite fully resolved.”

Framing the Discussion

“Working thought” is also an appropriate descriptor of Crosby’s curatorial approach. He sees his role as opening complexity rather than pinning down a static understanding of exhibit themes. “The provisional is our responsibility,” he says. “This exhibition is about bringing people closer to the riskiness of art and to the multifaceted roles of artists in our society and the positions they take.”

To accomplish this, Crosby researched contemporary artists nationwide while also mining the museum’s collection. “In many ways this exhibition is always already on view,” he says, noting the persistent theme of labor and the economy throughout Carnegie Museum of Art’s permanent collection, including Trade Canoe: The Surrounded, acquired by the museum in 2020 and making its debut in Working Thought.

Crosby says the museum itself—both its history and its physical space—will serve as a frame for the exhibition. “Attuning visitors to our history while looking at these artists allows the work to resonate more deeply,” he notes.

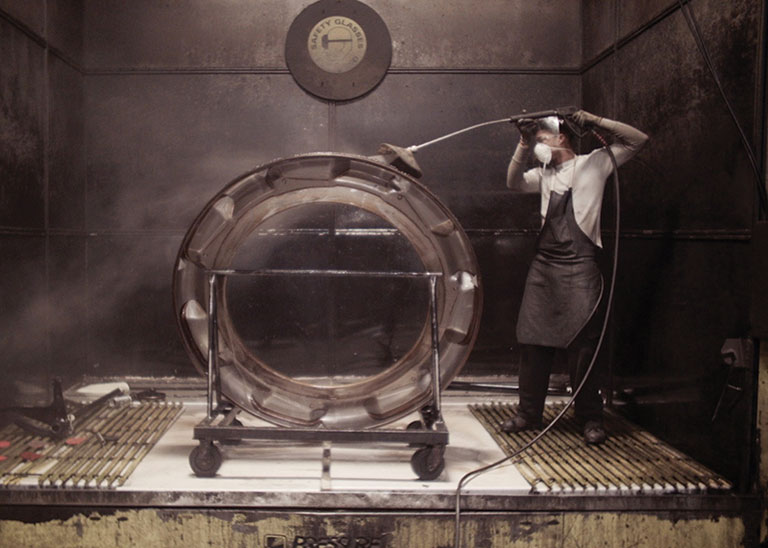

Kevin Jerome Everson’s eight-hour film Park Lanes, which documents a factory day in real time, will play in the Heinz galleries as part of Working Thought. It was originally shown at the 57th Carnegie International in the lobby of the museum’s Grand Staircase, framed by John White Alexander’s 1907 mural The Crowning of Labor. Taking up some 4,000 square feet, the mural depicts idealized images of labor, with muscular laborers swaddled in the billowing white clouds of industry. Now part of the museum’s collection, Everson’s film allows visitors to experience the actual rhythms of a present-day factory.

Kevin Jerome Everson, Park Lanes (film still), 2015, Carnegie Museum of Art, The Henry L. Hillman Fund, Courtesy of Andrew Kreps Gallery

“The relationship between art, economy, and labor hasn’t been fully explored at this museum, which has as its historical context the rise of industry in Pittsburgh.”

-Eric Crosby

John White Alexander, The Crowning of Labor (detail), 1907, Carnegie Museum of Art

Crosby’s goal in Working Thought was to have an open conversation between contemporary art and the museum’s past—one that visitors are free to explore and question. And he wasn’t interested in shunting the work into a neat historical survey.

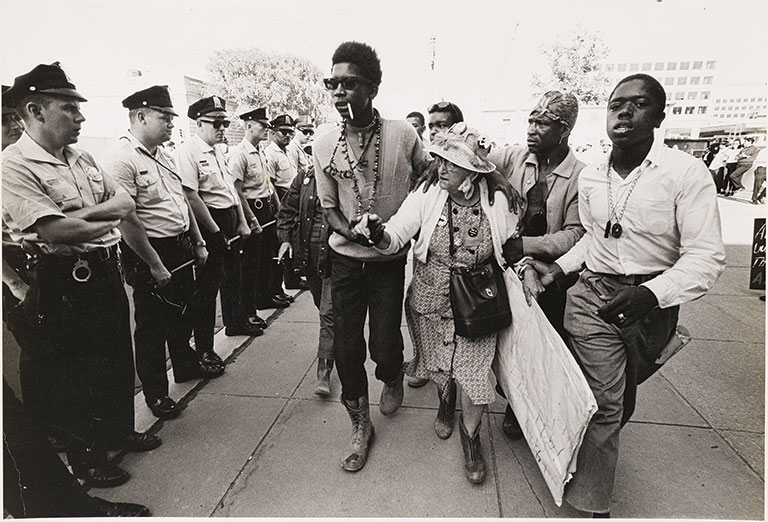

While not organized chronologically, the exhibit does have a “generational touchstone,” he says. The earliest pieces include Jill Freedman’s photographs of the 1968 Poor People’s Campaign, the historic push for economic justice that culminated with a march to the National Mall in Washington, D.C., where a protest encampment lasted for six weeks. In Hands Like a Shawl, the Pittsburgh-born photographer captures a group of young Black men tenderly assisting an elderly woman pass through a row of police offers holding batons at the ready. “Freedman documents this pivotal protest movement with indelible photographs that transcend the specificity of a moment and speak to a larger set of universal, humanistic concerns,” says Crosby.

Jill Freedman, Hands Like a Shawl, 1968, The Henry L. Hillman Fund

Grounded in the Local

“It’s important to bring nuance to a topic that can be viewed as polarizing,” reflects the museum’s Richard Armstrong Curator of Contemporary Art, Liz Park. “The museum is a place where we can see a whole gradation of experiences.”

Park finds that nuance in the work of artists like Cameron Rowland, who examines the role of the artist within institutions and economic systems. Part of the museum’s permanent collection, Rowland’s found-object work Norfolk Southern (Georgia) is a section of relay rail from a company that once used convicts who were forced to perform railroad work so dangerous no one would take it on voluntarily.

In the artist’s research-based practice, they discovered that the provenance of the relay rail links it to Pittsburgh-based U.S. Steel through a series of mergers. The artwork not only points to a history many people are unfamiliar with, it also raises questions about how objects enter museums and accrue both cultural and monetary value. “This work looks at the artist’s implication in the museum,” says Park. “None of us are outside of the system, and artists are really good at pointing to our participation in it.”

Moyra Davey, 1943 (Carnegie) (detail), 2008, Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Buchholz, Purchase, gift of Mr. and Mrs. William Block, by exchange

Another artist who incorporates into her work materials tied directly to the steel industry is photographer Moyra Davey. In 1943 (Carnegie), she photographed pennies minted from steel during the World War II copper shortage. But instead of taking on the expense of crating and shipping these close-up images of oxidization and disintegration, the artist printed them as 18-by-12-inch photos, folded and taped them, and then labeled and stamped them and mailed them to museum staff members. They’ll be shown as part of Working Thought —canceled stamps, creases, and all. “She is thinking about how we make judgments about value,” Park notes. “It’s a really subtle work that speaks to how this grand scale of capitalist industry gets folded into tiny units.”

Kiki Teshome, the museum’s Margaret Powell Curatorial Fellow, explains, “Many of the pieces in the exhibition are grounded in the local because Carnegie Museums’ history is relevant for the subject matter.” Other local representation in Working Thought: a screening of Braddock-based documentarian Tony Buba’s Lightning Over Braddock as part of a planned film series, and a commissioned work of a wood carving related to the 1889 Johnstown flood by Aaron Spangler.

Tony Buba, Lightning Over Braddock: A Rustbowl Fantasy (film still), 1988, Courtesy of Braddock Films Inc.

Portland-based artist Jessica Jackson Hutchins is integrating imagery from The Crowning of Labor into stained-glass skylights to be installed in the ceiling of one of the Heinz galleries. She’s adding imagery from the COVID-19 pandemic, including the “Stop the Spread” graphic. “It’s wonderful to witness how artists have adapted to working through a pandemic,” says Teshome, noting that the curatorial process for Working Thought was prolonged by the shutdown.

Shuttering the museum doors for three months at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic gave Museum of Art curators the chance to reconsider the concept of work. “Working from home changes how we think about work,” says Park. “The work site was a place of social interaction, and that has changed. These shifts informed how we thought about the exhibition.”

Stories in Art

The challenges of the pandemic also led the museum to explore new ways of connecting with the community.

In 2020, Carnegie Museum of Art provided art supplies to Casa San José, a local group that supports Latinx immigrants through language classes, youth programs, and other services. And the museum continues its relationship with the nonprofit through commissioned sculptures for Working Thought by Margarita Cabrera, an artist who collaborates with Latinx immigrant communities on her socially engaged art projects.

The Mexican-born artist and educator held two workshops with Casa San José as part of her larger project Space in Between, which she began in 2010 to establish networks of support among newly arrived immigrants and more established members of the immigrant community. Each iteration of the project begins with workshops in which community members recount the story of their journeys here—some painful and traumatic, others triumphant. Cabrera distills the stories into colorful pictograms and words embroidered on cacti crafted from border-patrol uniforms that the artist finds at flea markets. The cacti are emblematic of the dangerous terrain many people brave as immigrants, and they bloom out of terra cotta pots with hand-stitched images of stars, the Virgin Mary, and hearts, along with words like “futura” and “familia.”

Margarita Cabrera, installation view of Space in Between series at Dallas Contemporary, 2019, image courtesy of the artist and Talley Dunn Gallery, Photo: Kevin Todora

“The stories surrounding this project are really the heart of the piece because stories represent us, represent important moments in our lives,” Cabrera told ARTnews in 2018. “In order to tell a story, we need to be able to listen to someone telling their story.”

The title of Cabrera’s piece refers not only to the dangerous border space but also to nepantla, a concept from Chicana writer Gloria Anzaldúa. Anzaldúa uses this Indigenous Nahuatl word for “the space in the middle” to describe spaces in which people experience solidarity across differences and create new cultural practices. “The museum can learn from artists like Cabrera to be more expansive in the communities they engage,” says Teshome. “She shows how art can be redemptive, empowering, and healing.”

Looking closely at the cacti, viewers will spy servers balancing trays and farm workers bending to tend crops. These images pay homage to the underappreciated labor performed by some members of the immigrant community.

“The museum can learn from artists like [Margarita] Cabrera to be more expansive in the communities they engage. She shows how art can be redemptive, empowering, and healing.”

-Kiki Teshome, Carnegie Museum of Art Margaret Powell Curatorial Fellow

“One of the aims of the exhibition is to present the diverse ways artists are grappling with issues of economic inequality, not only in content but also in process and mediums,” Teshome adds. “I am hoping that when visitors come, they will have a dynamic understanding of how artists are engaging in these issues and can expand their own understanding as well.”

This means presenting images of work that might have discomforted the museum’s founder.

“The current relationship between the museum and its public is far more complex than it was depicted in 1907,” says Crosby, referencing the date Andrew Carnegie commissioned Alexander to paint The Crowning of Labor, his testament to progress achieved through hard work and industrial power. “For a museum like ours to not probe its relationship to the history of industry and labor would be like a museum dedicated to modern art not questioning the received history of modernism.”

Part of the museum reconsidering its relationship to history is finding new ways to engage with the content of the permanent collection. For Crosby, each new acquisition is an opportunity to reassess all the acquisitions that came before. For example, Crosby sees a strong conversation between the aesthetics of the works of Quick-to-See Smith and another painter in the collection, the Canadian-American artist Philip Guston. He notes that this conversation will pick up after Working Thought closes.

“We are always thinking about our collecting practices,” Park adds. “The canoe in [Trade Canoe: The Surrounded] is a vessel full of things that is heading somewhere, and the museum is also a collection of things that is heading somewhere. So, the painting is a really beautiful metaphor of where we are.”

Significant support for the exhibition is provided by Kathe and Jim Patrinos, the Susan J. and Martin G. McGuinn Exhibition Fund, and the Virginia Kaufman Fund.

Generous support is provided by Brian Wongchaowart, with additional support from the Ford Family Foundation, Nancy and Woody Ostrow, and The Fellows of Carnegie Museum of Art.

Support for curatorial research has been provided by The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts