You are an animal. The same goes for everyone you’ve ever known and loved.

To be even more specific, you are a vertebrate, thanks to that interlocking column of bones in your back that stiffens after you fold too much laundry or shovel too much snow. You are also a mammal. (The eyebrows are a dead giveaway.) And you are a primate—a great ape, at that! Just wiggle those glorious thumbs.

We don’t often think of ourselves in these terms. Dogs and cats, horses and cows. Lions, tigers, and bears. Those are the real animals, you might say. Especially the ones that still live in nature. But us? We live in suburbs and apartment buildings. Animals live in the Amazon and the Arctic.

But you can’t really draw a neat line around nature. It’s the deer in your backyard, the birds at your windowsill, the ants between the sidewalk slabs. It’s the assembly of bacteria in your gut and the mites living between your eyelashes. And although many people now feel disconnected from the natural world, a slight recalibration in our thinking could do the planet a lot of good.

“We are deeply interdependent on nature, and nature depends on us,” says Nicole Heller, associate curator of Anthropocene studies for Carnegie Museum of Natural History. “It’s an entanglement that is at the root of everything.”

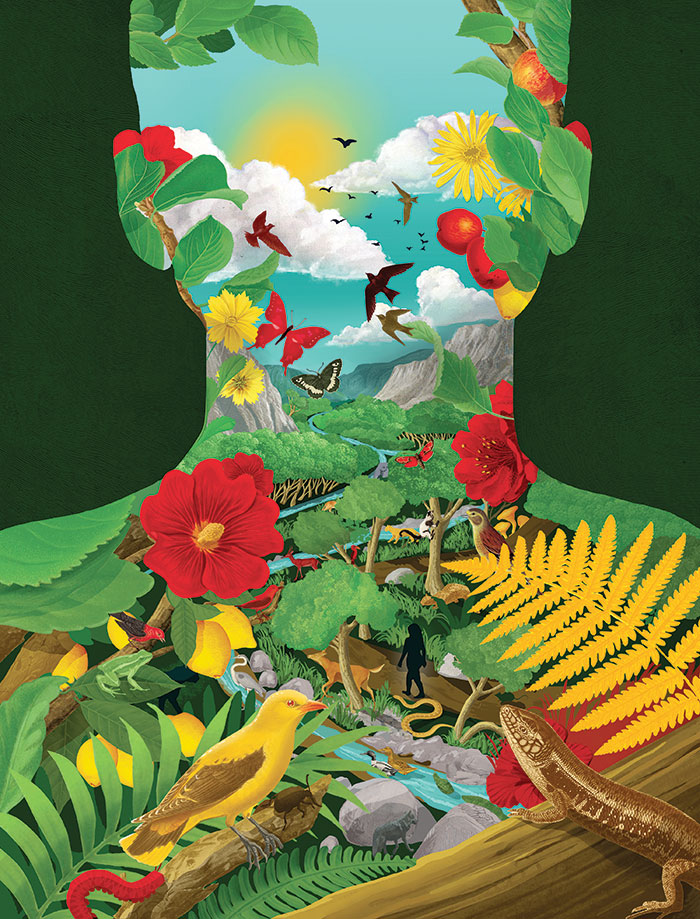

Illustration: Sam Falconer

As the world’s first curator of Anthropocene studies, Heller has been working with her colleagues to think about how the museum can help visitors reimagine the relationship humans have with the world all around us. Because the more we learn about climate change, the extinction crisis, and other global problems, the more scientists believe we need collective buy-in on the solutions.

Heller started her tenure at the museum on the heels of its popular 2017 exhibition We Are Nature: Living in the Anthropocene. “Coming out of that, we knew that we had a lot of interest from our community in these topics,” Heller notes. “We also knew that we had a lot to learn and a lot to keep working on.”

The museum is looking to keep the discussion going through a new original visitor experience. We Are Nature: A New Natural History features a hub gallery and 15 focal points interspersed throughout the museum’s exhibition galleries, each highlighting the connections between humans and the rest of nature from a different angle.

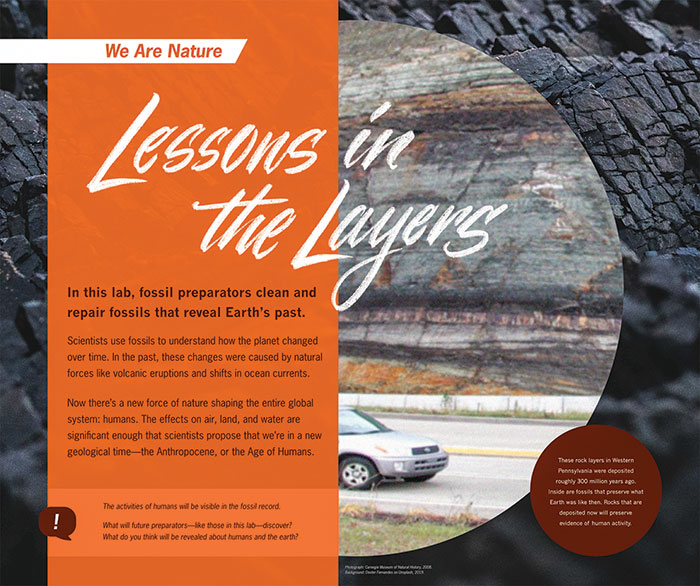

One example: Outside PaleoLab, where visitors watch as experts prepare fossils found deep in Earth’s geological layers, a We Are Nature installment called Lessons in the Layers considers how decoding the past can help us better understand the present.

Among the lessons learned in We Are Nature: Our actions today will likely show up in Earth’s rock layers millions of years from now.

When exploring Earth’s rocky layers, experts look for so-called “golden spikes,” or features that clearly separate one geological epoch from another. And while we can’t know exactly how humans will show up in the rock records millions of years from now, many scientists argue that future geologists will be able to see our handiwork beginning with the sudden appearance of radioactive elements after nuclear-weapons testing began in 1945. Others point to the unprece-dented increase in carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and captured in ice, the result of fossil-fuel use that began during the Industrial Revolution. Or maybe it will be plastic, or the disappearance of huge swaths of biodiversity everywhere humans leave their imprint.

The point is, everywhere you look, there we are. Which is why many scientists say that we are now living in a new geologic age called the Anthropocene (Anthro means human).

This is a tricky idea to get your head around—that the choices you make in Mount Lebanon or Wilkinsburg can have wide-reaching repercussions for plants and animals you may never meet. But to give you an idea of just how We Are Nature aims to illustrate those connections, let’s turn to the 350-pound gorilla in the room.

The Primate in Your Pocket

Walk through the Hall of African Wildlife and you’ll come face-to-face with one of the most impressive specimens on any floor of the museum: a massive silverback gorilla named George.

People love George, and it’s easy to see why. His hulking frame sits at ground level, which allows visitors to size up one of humanity’s closest cousins in the animal kingdom. But there’s also something about George’s eyes. They look straight ahead, making you feel like you’re not just gazing upon another piece of taxidermy, but instead an individual creature complete with desires, goals, and his own personal past. Truth be told, George came to the museum by way of the Pittsburgh Zoo, where he lived for 14 years in the 1960s and ’70s until a tooth abscess turned fatal.

Another lesson learned: The fate of gorillas like George is directly linked to human actions. | Photo: Joshua Franzos

How many museum visitors have been stopped in their tracks by George’s stare? How many have whipped out their smartphones to snap a picture of the magnificent primate, wanting to capture in some small way what it feels like to stand before him?

What most people don’t realize is that the mobile phone in your pocket and the fate of gorillas like George are linked, and not in a good way.

“Pretty much everything that has a battery, like cellphones and iPods, needs a metal called coltan to keep it from over heating,” says Jo Tauber, gallery experience manager at the museum. Short for columbite-tantalite, coltan is used to manufacture everything from laptops and electric cars to the turbines in plane engines. The problem, says Tauber, is that the metal is only found a few places on Earth, and one of those is the Democratic Republic of Congo—home to two species of endangered gorillas. The mining required to get at that coltan not only destroys gorilla habitat, but it also threatens the great apes with disease transmission from humans. The animals are also sometimes killed to be eaten or sold as bushmeat.

If you’re starting to get a queasy feeling about how all the gadgets in your life negatively affect beautiful wild animals, well, Tauber has some good news. To accompany the We Are Nature story about gorillas and coltan, the museum has partnered with Eco-Cell, a company that specializes in recycling electronics. The next time you visit, restore your old devices to their factory settings and then drop them into the designated bin. You’ll be helping to cut down on the need for more mining in the Congo. You might also consider hanging onto your device for a few years instead of rushing out for the newest model.

“That’s what We Are Nature is really about. Showing how we, as human beings, are connected to and are impacting nature. And how that doesn’t just mean our local nature.”

-Jo Tauber, gallery experience manager at Carnegie Museum of Natural History

Museum visitors are invited to recycle their old electronic devices on-site—a small but meaningful step toward reducing mining activities in the Congo that are endangering two species of gorillas.

“It’s a simple action that people can take,” says Tauber. “Because, a lot of times, when we’re telling conservation stories, it can feel hopeless, and people don’t know what to do.”

Now, a single act—like tossing a cellphone in a bin—isn’t going to solve the problem. But lots of people being mindful of lots of old electronics can make a dent in the need for new rare metals. And acknowledging the unseen costs of our purchases can help influence future behavior.

“That’s what We Are Nature is really about,” says Tauber. “Showing how we, as human beings, are connected to and are impacting nature. And how that doesn’t just mean our local nature.”

The Pronghorn on Your Parkway

Out west, there’s an animal so fleet of foot it would break speed records on many a local street. You may know it as the pronghorn.

Pronghorn are evolutionary weirdos, with giraffes being the species’ closest living relative. They have horns like rams, which fall off every year like deer antlers. And how about their top speed of 53 miles per hour? Some scientists think pronghorns got so fast trying to escape predators that no longer exist—such as the long-legged predator known as Miracinonyx, or today’s American cheetah.

Each year, many pronghorn populations migrate hundreds of miles south to find food during the winter. But in just the past few decades, these migratory mammals have discovered all sorts of new obstacles, including human developments, gas wells, barbed-wire fencing, and road after road after road.

“Pronghorn are very concerned about crossing roads,” says Andrew Jakes, Great Plains science manager for the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute. “They see vehicles as predators.”

“I put a lot of currency into the fact that I’m just one species in this whole world. And I think it’s important to find correct conservation and management opportunities for all wildlife and their habitats.”

-Andrew Jakes, Great Plains Science Manager for the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute

The thing is, some of these populations have been traveling the same paths for more than 6,000 years. Which means that particular stretches of highway lead to certain death for too many pronghorn every year. And because cars aren’t going away anytime soon, scientists, conservationists, and wildlife managers had to come up with another solution.

First, the U.S. Forest Service established the nation’s first designated wildlife migration corridor in Wyoming in 2008. This promised to cut down on the number of fences, roads, and natural gas wells that could be built between the pronghorn and their winter pastures. But the bigger move came when the Wyoming Department of Transportation (WYDOT) and the Wyoming Game and Fish Department teamed up to build a series of overpasses and underpasses along a stretch of U.S. 191 where pronghorn, deer, moose, and many other animals try to cross each year.

“Individuals started using that overpass almost immediately,” says Jakes of the Trapper’s Point overpass, which was completed in 2012.

Concrete arch bridges like this one built over U.S. 191 in Wyoming offer pronghorn and other animals safe passage as they migrate hundreds of miles south each winter in search of food. | Photo: Courtesy of Wyoming Game and Fish Department

This isn’t just good for wild animals, by the way. The new routes reduced vehicleand-animal collisions by about 80 percent, according to WYDOT. That’s a huge figure, especially when you consider that this stretch of highway used to pile up around half a million dollars’ worth of accidents each year.

Projects like these require buy-in not only from federal, state, and local government agencies, but also from private landowners, conservation organizations, and citizens, whose tax dollars pay for the wildlife passes. But the result—which you can learn more about in the Hall of North American Wildlife’s exhibit entitled Designing for Connection—is worth it for a more existential reason.

“I put a lot of currency into the fact that I’m just one species in this whole world,” says Jakes. “And I think it’s important to find correct conservation and management opportunities for all wildlife and their habitats.”

The Ants in Your Mirror

Many experts say humanity stands at a crossroad, and the decisions we make now will determine the quality of life for billions of people in the century to come. It’s a daunting proposition, but Heller says there’s hope to be found—if you know where to look.

“I really think you could argue that everything we do, ants do, too,” says Heller. “There’s a lot of war, and violence, and even slavery. But there’s also incredible collaboration, and reciprocity, and building of societies.”

Heller, who was the lead curator for the We Are Nature project, holds special regard for its Social Species Make Big Impacts section located in the museum’s Discovery Basecamp area. Her research background is in ant behavior, and she says she finds inspiration in watching and studying these insects. Each is tiny and largely insignificant. If one animal were to be lost, the colony would go on. But together, ants can excavate mountains’ worth of soil, strip forest floors bare, or transport thousands of their young in the face of a catastrophic flood.

“Ants offer a microcosm for thinking about the effects of humans on the planet, and the power of cooperative behavior, both for better and for worse.”

-Nicole Heller, Associate Curator of Anthropocene Studies for Carnegie Museum of Natural History

Photo: Troup Dresser

“We don’t often think about the power of being a social species,” says Heller. “I think, overall, the lesson is a positive one about the benefits of collaboration.”

Perhaps We Are Nature visitors will leave not only with a better appreciation of how people fit into the greater whole but also emboldened by a new mission: Be the ant you want to see in the world.

“Ants offer a microcosm for thinking about the effects of humans on the planet, and the power of cooperative behavior, both for better and for worse,” says Heller. “With We Are Nature, we want to open up conversations about how people are a part of nature and the consequences of our behavior.

“Cooperation is a key human trait, but we can’t only cooperate to make the planet suitable for people; we need to also care for the other species around us to make life abundant and diverse,” she says. “That is really the key to sustainability and livability.”