In a school year like no other, civics teacher Jen Miller says there were plenty of newsworthy events in 2020 to help her ninth graders at Pittsburgh Science and Technology Academy connect their coursework to their own lives. Learning virtually, the classes discussed everything from the presidential election to the Black Lives Matter movement. And with an eye toward the local, the central New York native often leans into the Teenie Harris Archive at Carnegie Museum of Art to help students unpack the complexity of the place they call home.

Q: It must be an interesting moment to teach civics?

A: What’s great about civics is there really is no typical year. The skeleton is always the same, but there’s always something current. We, as adults, know that, and we follow it. But the ninth graders do, as well. So, it’s really easy for me to have a hook into the class, because most kids have something that they’re following or that they care about that lines up with what we’re going to discuss. In 2020, there was a surplus of topics to talk about. When we started back to school in August, that was the peak of the social justice movement that was happening over the summer. Because they hadn’t been in a formal setting to talk about it, students were pretty eager to start.

Q: How did that unfold?

A: The concept of social justice is something that the students have threaded through the course, sometimes in ways that I expected, and other times in ways that I did not. We started off the year talking about what are the big stories going on right now? And it was the election, and it was the Black Lives Matter movement. A few weeks into the school year, I was teaching them about the census, and I didn’t expect them to tie in the ideas of resource allocation and social justice. I was so impressed with their abilities to make that connection without me having to lead them there. And because they got there sooner than I thought they would, they were really able to dig into it. They quickly understood what the census is and what it’s for, and got right to the question of, “But is that information used fairly?” These are public school students. So, when I tell them that the census is used for the federal government to allocate resources to states and it can trickle down to the local level, they know that their school is publicly funded. I did not have to ask, “How does this affect you?”

Q: Can hot-button issues be a challenge?

A: A lot of thought goes into how we, as teaching staff, structure the questions to make it a discussion between the students; we want to allow space for students to discuss their potentially conflicting views and don’t want to incite problematic issues. It’s something that I’m a lot better at now than I was when I started, for sure. The students are a lot better at it, too, because over the last 10 years, since I’ve been teaching, there’s been more of a focus on bringing topics that are relevant to students’ lives into the classroom. So, the more we do that, then the more skilled the students become because they have a chance to practice.

Q: You use an inquiry-based approach.Can you explain that?

A: Inquiry is an important part of the class, and each day is structured around a question. Today their question was, “Where do your opinions come from?” And then I specifically asked, “On a scale of one to 10, how much do you think your views are shaped by what you see in different forms of media?” So, the overall topic of each day and of each unit is determined by me, with the curriculum. But the personal connection comes from them, because they’re being asked to make these reflections about themselves and about their lives in conjunction with what they’re learning. That’s what civics is.

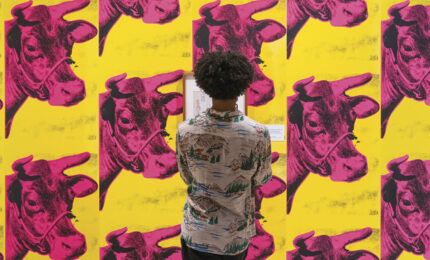

Q: Can you give an example of how you’ve incorporated the work of Teenie Harris?

A: When [Teenie Harris Archivist] Dominique Luster comes to class, for example, we link the work of Teenie Harris and [former Pittsburgh Mayor] David Lawrence. We reflect on how someone’s work can be very positive and very negative simultaneously, to resist putting someone in a bucket of a good or bad mayor. Growing up in Pittsburgh, students know it used to be a heavily polluted and decaying city—we look at images from the ‘40s, not by Teenie, when the lights were left on in the daytime it was so dark and smoggy—and then at images when it was cleaned up and developed. And they get that local government affected that. Teenie’s images of the demolition of blocks of homes and businesses in the Lower Hill District to make room for the construction of the Civic Arena, of people watching and protesting the demolition, help us look closely at what took place—and who was affected—in order for those changes to be made. It’s complex. I could do all the explaining in the world, but when the photographs are there, it’s direct and powerful.