To say the critics of the day were unimpressed with the works artists Andy Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat created together would be kind. Vivien Raynor of the New York Times likened the duo’s 1985 gallery debut to Oedipus Rex, the epic Greek tragedy about the guy who ends up killing his father and sleeping with his mother.

“Warhol, one of Pop’s pops, paints, say, General Electric’s logo, a New York Post headline, or his own image of dentures; his 25-year-old protégé adds to or subtracts from it with his more or less expressionistic imagery,” wrote Raynor. “The 16 results— all ‘Untitleds,’ of course—are large, bright, messy, full of private jokes, and inconclusive.”

Dubbed Paintings, the show, which confronted topics of race, capitalism, and the process of artmaking, was the culmination of an unlikely three-year creative collaboration and personal friendship between the artists that ended just two years later with Warhol’s untimely death.

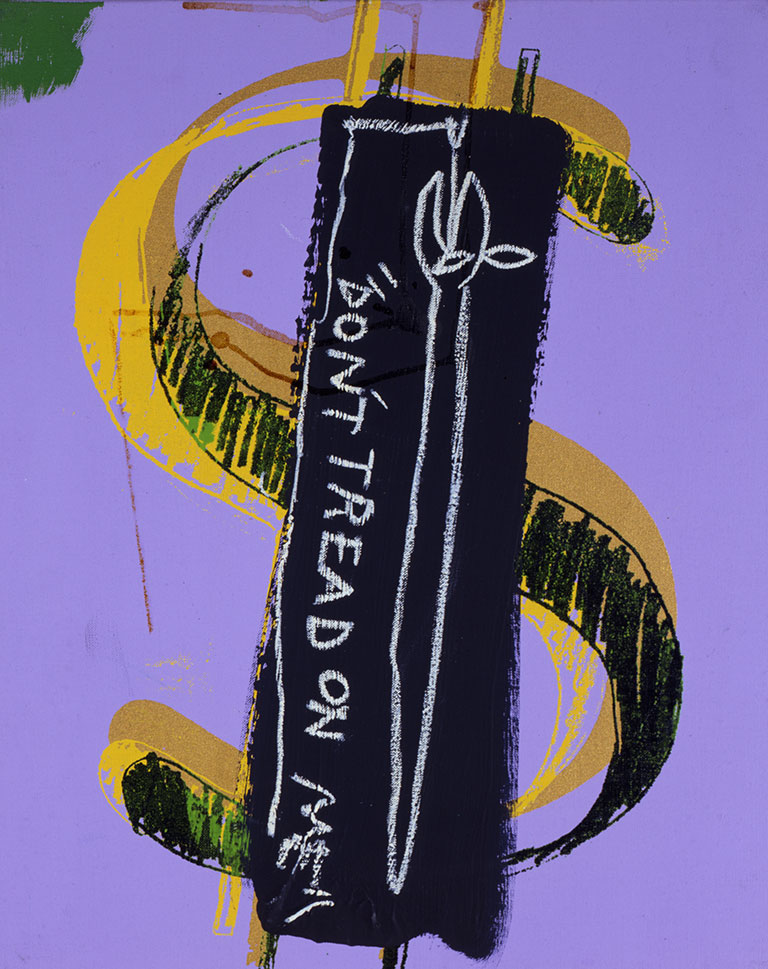

Jean-Michel Basquiat and Andy Warhol, Collaboration (Dollar Sign, Don’t Tread on Me), 1984–1985, The Andy Warhol Museum; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat

“The reviews were wounding,” says Jessica Beck, The Andy Warhol Museum’s Milton Fine Curator of Art. At the time, she notes, “Warhol was known more for his celebrity than his painting and, in many ways, had hoped the show would reposition his reputation in the gallery scene. Basquiat saw an opportunity for further success. But the press saw their union as a setback.”

Today Beck is looking at the pair and their collaborative works anew. For the first time in The Warhol’s history, she’s bringing out all of the museum’s holdings related to Basquiat, including photographs, archival materials, paintings, even his appearance on Warhol T.V. that defined the artists’ brief but intense relationship. “With fresh eyes, one can see an undeniable contemporary vibrancy and balance in these works,” she says.

The timing is no accident. “After George Floyd’s murder last summer, I started thinking about Warhol’s connection to race and stories that can be told within our collection,” Beck says. “It was Basquiat who encouraged Warhol to connect to the political conversation at that moment.”

And those conversations sound eerily similar to what we’re confronting some 40 years later.

“Given the traumatic cultural moments we’ve been experiencing—from the pandemic to the murder of George Floyd—this installation brings new relevance to the AIDS crisis of the 1980s as well as the 1983 death of a young Black artist named Michael Stewart at the hands of white police officers,” says Beck.

Beyond Face Value

On the surface, it would appear that Warhol and Basquiat had little in common. Warhol was white, queer, and ever self-conscious about his appearance. Basquiat was Black, straight, and by all accounts beautiful. By the time the two were formally introduced in 1982, Warhol was in his 50s and, some would argue, already past his peak. At age 21, Basquiat was more than primed to ascend the throne. Having gained street cred as part of the graffiti-art-poetry squad known as SAMO© (said to stand for “same old shit”), he was headlining gallery shows in Los Angeles and Milan, Italy.

But the pair discovered intimate connections, among them physical scars of past traumas—Warhol was shot by a would-be assassin in 1968, the same year an 8-year-old Basquiat was hit by a car and had his spleen removed. They shared a Catholic upbringing and the immigrant experiences of their parents. Warhol’s roots were in the Carpathian Mountains of what is now eastern Slovakia, and Basquiat’s father was from Haiti and his mother from Puerto Rico. And because neither Warhol nor Basquiat fit neatly into the art establishment, they shared a certain outsider status.

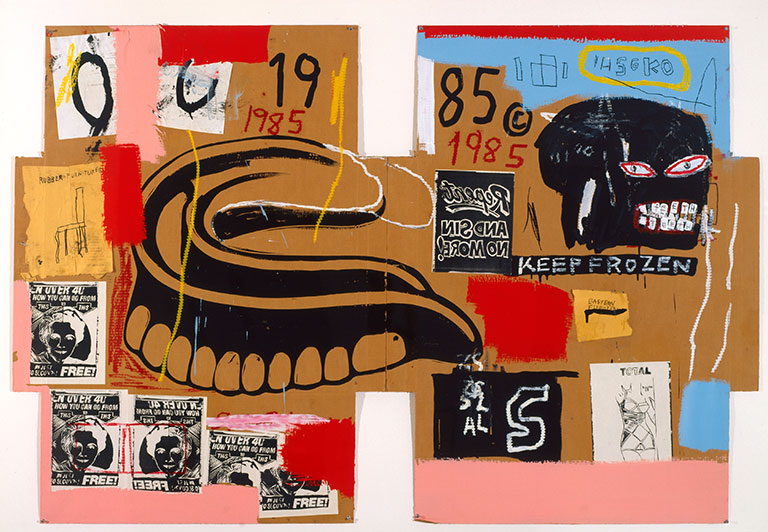

Jean-Michel Basquiat and Andy Warhol, Dentures/Keep Frozen, 1985, The Andy Warhol Museum; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat

“In a word, their relationship was complicated,” says Michael Dayton Hermann of The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. “They inspired each other, traveled together, partied together, exercised together, got their nails done together, painted together, and painted each other.

“Basquiat had the freedom, trust, and respect to write over what Warhol had put on the canvas, and vice versa.”

– Jessica Beck, The Andy Warhol Museum’s Milton Fine Curator of Art

“Yet, despite the sincerity of the relationship,” the author of the 2019 book Warhol on Basquiat continues, “they were both ambitious and smart enough to recognize and exploit the mutually beneficial opportunities the friendship allowed for their careers.”

As Basquiat’s star continued to climb in the ’80s, so did his spending. Warhol was able to provide practical advice on how best to manage sudden fame and fortune.

“Basquiat goes from selling his art postcards on the streets to selling out his solo shows with [legendary gallerists] Mary Boone and Larry Gagosian,” Beck says. “That kind of wealth and attention can be overwhelming. Warhol critiques his lavish spending and tries to help him navigate the gallery world.”

And it was Basquiat’s very presence in the studio—his youthful exuberance— that prompted Warhol to start painting by hand again.

It’s not that Warhol wasn’t working prior to Basquiat’s arrival. He was. For Warhol, much of the ’70s was about the iconic silkscreened portraits, many commissioned by wealthy socialites and celebrities, he created from Polaroids and other source materials. It was certainly a productive time, but perhaps not as inspiring or inspired.

“Warhol commented in his diaries about how quickly Basquiat could paint,” Beck says. “He was surprised, even envious, of Basquiat’s pace and also his confidence—a confidence of the hand, the gesture, and the mark on the canvas. Basquiat was mesmerizing to Warhol for both his youth and his undeniable talent. I think it was a reminder to Warhol that painting could be energetic and physical.”

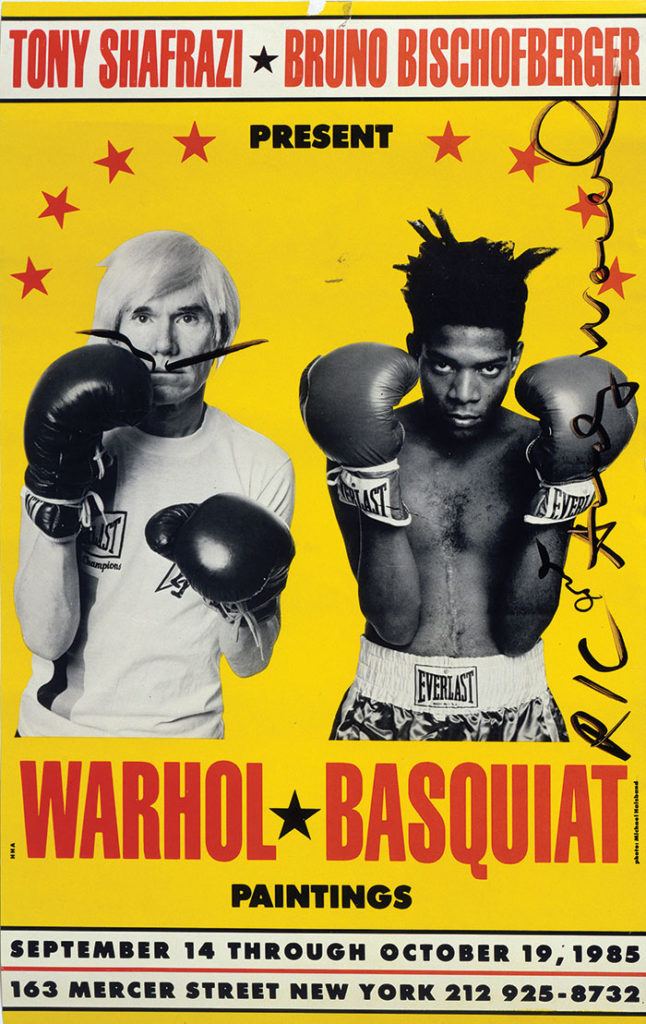

A promotional poster for the pair’s 1985 Paintings exhibition at the Tony Shafrazi Gallery.

The two developed a trust that found its way into the gym and onto the canvas. Boxing, a subject Basquiat grappled with in several paintings, became the centerpiece for the posters touting their Paintings show—a recommendation of the gallery owner, not the artists. And sparring—a give and take, a back and forth—became their signature move when working together.

“It was like a dance,” Beck says. “Warhol would paint an advertisement logo and then Basquiat would do a gesture over top of it. Then Warhol would come again with something else and Basquiat would make another imprint. It was a trust exercise. Basquiat had the freedom, trust, and respect to write over what Warhol had put on the canvas, and vice versa,” she continues. “There was an enormous amount of respect between them.”

History Repeating

But perhaps nothing influenced the pair more than the time and place in which they worked. New York in the 1980s was fraught with matters of life and death, sin and forgiveness, fear and faith.

The city was on the brink of panic as a yet-to-be-identified AIDS epidemic devastated the gay community, and on the verge of civil unrest as people confronted the circumstances of Michael Stewart’s death.

In the early hours of Sept. 15, 1983, several white Port Authority police officers arrested Stewart for allegedly tagging a subway car. During the violent encounter, the young artist was severely injured by police. He died 13 days later. While exactly what happened during the arrest remains unsettled, a grand jury failed to indict officers on charges ranging from criminally negligent homicide to perjury. A subsequent settlement was awarded to the Stewart family.

After Stewart’s death, Basquiat was often heard telling friends, “It could have been me.”

A 1984 collaboration between Basquiat, Warhol, and Italian painter Francesco Clemente, this sculpture pays homage to the death of artist Michael Stewart. © Francesco Clemente

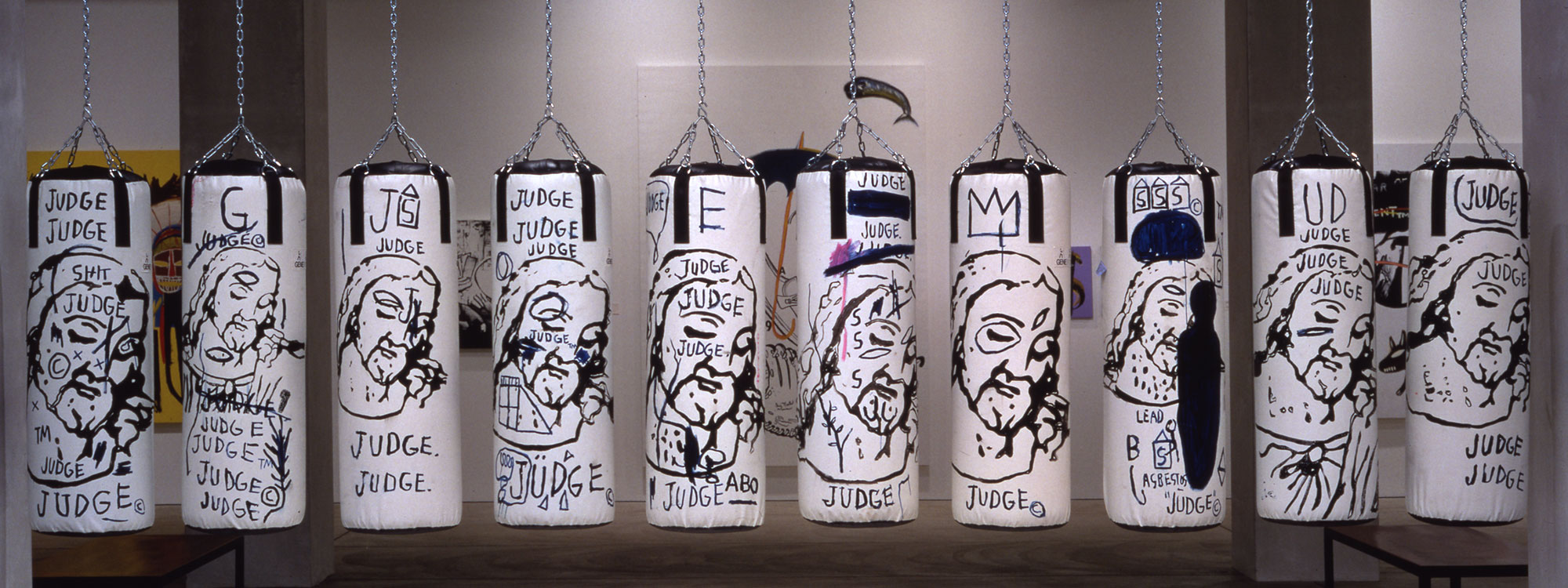

To be featured in the fourth-floor installation is a sculpture created by Warhol, Basquiat, and Italian artist Francesco Clemente that directly references the death of Stewart, and the pairing of Warhol’s The Last Supper (The Big C) with Ten Punching Bags (Last Supper), a collaborative piece by Warhol and Basquiat that was never shown during their lifetimes.

These two works in particular seem to speak to Warhol’s growing political voice, a voice, Hermann says, Basquiat helped him find. “It is my view that Basquiat reignited Warhol’s passion for painting,” he says, “stoked his ambition to remain relevant, and forced him to consider what it means for someone to be Black in America.”

Beck makes the case that as Warhol continued to explore and expand his Last Supper series, many of his later canvases contained allegorical or symbolic gestures that reflected the serious issues of the day. One example is The Big C, which she argues is a reference to “gay cancer,” as AIDS was known at the time. In this work, she points out that Warhol gave the disease a face. “It is the mournful and benevolent face of Christ,” says Beck.

Christ is front and center in Ten Punching Bags as well. On each bag, the face of Jesus is shown with spots that progressively begin to look more like lesions or wounds, or perhaps the sarcomas associated with AIDS. On one bag Basquiat added a black armless figure, reminiscent of the image he painted on Keith Haring’s studio wall shortly after the death of Stewart.

“For me,” says Beck, “Ten Punching Bags is this stunning, layered portrait of the personal and political experiences that Warhol and Basquiat were both grappling with in New York in the 1980s.”

The pair’s relationship, however, never regained its footing after the negative reviews of the Paintings exhibition. “Jean- Michel hasn’t called me in a month. so I guess it’s really over,” Warhol wrote in his diaries in November 1984.

In a few short years, it really was over. Warhol died unexpectedly in February 1987 following complications from gallbladder surgery. He was 58. Basquiat was said to be devastated. Less than two years later, he, too, would be dead from a heroin overdose at age 27.

“While the ending of their story is tragic,” Beck says, “the intensity and vibrancy of their union is remarkable. It was a friendship of trust and inspiration that changed both of their lives.”

Receive more stories in your email

Sign upTags:

Art