Having surpassed the half-millennium mark, it’s not surprising that Mona Lisa has officially retired from touring. Her fragile condition, including a small crack stretching from the top of the painting to her hair, has prompted those around her to insist that she stay put in her Paris home. It’s at the Louvre, protected within the environs of a climate-controlled box that’s stored behind bullet-proof glass, that Mona Lisa continues to greet her legion of adoring fans with that eternal “it girl” smile.

But there was a time when Leonardo da Vinci’s masterwork—the portrait of a woman thought to be Lisa Gherardini, the wife of a Florentine cloth merchant—took America by storm in an albeit brief tour de force. The year was 1962 and the event was made possible by another beautiful, enigmatic woman—then first lady Jacqueline Kennedy.

Jackie had prevailed upon France’s minister of culture to allow one of his nation’s most treasured icons to be seen by a whole new world of admirers. Sailing across the Atlantic, Mona Lisa arrived in the States in late December 1962 and was escorted amid much pomp and circumstance to her first stop: the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., where she was on view from January 8 through February 3, 1963.

President John Kennedy and Jackie, Vice President Lyndon Johnson and Lady Bird, the entire U.S. Congress, members of the Cabinet, members of the Supreme Court, and assorted other dignitaries enjoyed a private meet and greet with Mona Lisa before the general public got its chance.

Young visitors get their first glimpse of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa at the National Gallery of Art, Jan. 14, 1963, in Washington, D.C. (AP Photo)

A few weeks later, she made her second and final stateside guest appearance at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. By March, Mona Lisa was gone, on her way back home where she’s been a permanent fixture (except for one other brief excursion in 1974 that took her to Tokyo and Moscow) ever since.

News reports estimated that more than 1.5 million people—some waiting in line for hours in the unforgiving cold—went to find out for themselves what all the centuries of fuss was about.

Andy Warhol, however, took the sensation at face value. It was likely a reflection of the times that inspired Warhol to produce his own Mona Lisa—the first of many variations—within months of the Met show.

The price of fame

The elements of celebrity and adulation, beauty and tragedy can be seen in Warhol’s choice of subjects throughout the early 1960s. His famous Marilyn [Monroe] series was created shortly after the star’s death in 1962, and his Jackie paintings, which show the former first lady in the moments before her husband’s assassination and in the days following, debuted in 1964.

Then there was Mona. She, too, suffered her share of trials and tribulations. She was kidnapped in 1911 (and returned two years later) and attacked on two separate occasions in 1956. One vandal threw acid, the other a rock. But she’s a survivor, and, like Marilyn and Jackie, she remains in the collective consciousness of the West to this day.

“He might have seen Mona Lisa as a celebrity, garnering enough attention to dominate the press for the time she was here,” says Jose Diaz, chief curator at The Andy Warhol Museum. “Warhol saw it as a contemporary moment and took advantage of honoring one of the great masters of the Renaissance.”

And so it seems Warhol was not the least bit intimidated by her pedigree.

Andy Warhol, Mona Lisa (depicted), Mona Lisa, ca. 1979, The Andy Warhol Museum; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

“I don’t think Warhol would have had any hesitation at all,” Diaz continues. “He must have enjoyed it and relished in the thought of appropriating one of the most recognized images from art history.”

Given Warhol’s adman background, that’s not surprising. Long a tool of marketers, Mona Lisa has hyped just about everything from car insurance to humidifiers and shoe polish.

She had also been parodied by other artists, including one of Warhol’s greatest influences, Marcel Duchamp. In 1919, on a reproduction of a postcard, Duchamp impishly drew a goatee and a moustache on Mona’s smiling face, dubbing the work L.H.O.O.Q. (which, former Warhol chief archivist Matt Wrbican pointed out in his exhibition Twisted Pair: Marcel Duchamp and Andy Warhol, sounds a lot like French slang for “she’s got a hot ass”). It created a public outcry.

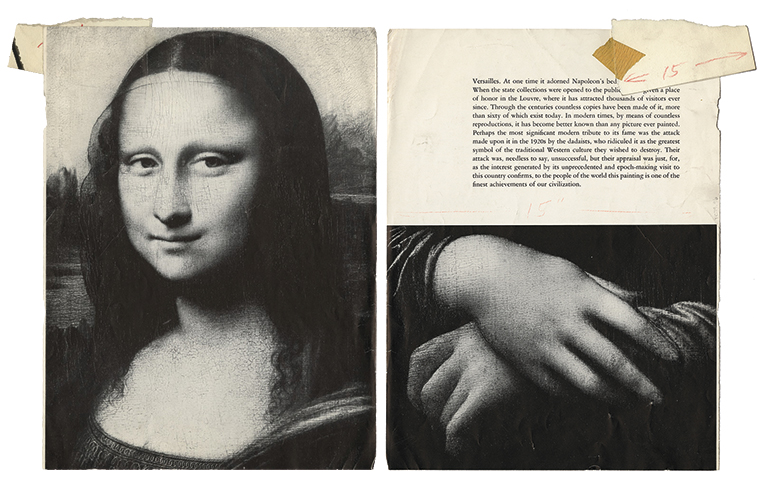

Like Duchamp before him, Warhol used existing images of Mona and made them his own. Warhol looked no further than the Met’s brochure touting her triumphant arrival in the U.S. The brochure, featuring the three photos he used—a full portrait, a cropped headshot, and a close-up of her hands—can be found in The Warhol’s Archives.

Magazine tearsheets (Mona Lisa), ca. 1963, from Time Capsule 79, The Andy Warhol Museum; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

Appropriating source material from a variety of mediums (think 1962’s Campbell’s Soup Cans) is one of the defining characteristics of Warhol’s art. His still-evolving silkscreening technique provided him with the means to quickly transform those singular images into multiples on canvas. Among his most ambitious Monas was a five-by-six grid titled Thirty Are Better Than One.

“Warhol was reinventing Mona Lisa or re-presenting something that was familiar,” Diaz says. “He doesn’t make her as a single focal point; there’s the seriality in his work. It almost becomes like decorative wallpaper, a repetition of information. And that’s pretty typical of Warhol’s work, whether it’s Mona Lisa, Marilyn, or Jackie.”

The gift of Pop

Also typical for Warhol was his penchant for revisiting some of his previous subjects. By the late 1970s, he was once again smitten with Mona, producing multiple versions in various sizes. Several were diptychs. Examples of Warhol’s monochromatic treatment, white on white and gold on white Mona Lisa paintings, are part of The Warhol’s permanent collection.

In 1984, Warhol broadened his retrospection in his Details of Renaissance Paintings. As the title aptly states, he sought to refocus attention on a single aspect of several classic works—like Botticelli’s Birth of Venus and Leonardo’s Annunciation.

Before Warhol’s death in 1987, Leonardo would once again serve as his muse in what would be Warhol’s final series. A commissioned project, The Last Supper series took two years to complete and encompasses more than 100 paintings, silkscreens, prints, and works on paper.

Later this year, coinciding with the 25th anniversary of The Warhol and the 500th anniversary of Leonardo’s death, the exhibition Andy Warhol: Revelation will explore the fascinating connections between religion and Pop, Leonardo and Warhol. Curated by Diaz and hosted by The Warhol, the first-of-its-kind exhibition will bring to light, among many other works, Warhol’s Mona Lisa, The Annunciation, and Last Supper series.

“Warhol encompassed the culture of his period just as da Vinci did. I think da Vinci would be flattered.” – Jose Diaz, chief curator at The Warhol

The two artists, Diaz says, are truly kindred spirits. “Da Vinci was a Renaissance man in the sense that he gravitated beyond painting, embracing the sciences, architecture, music, and more.

“Warhol in his own right was a Renaissance man, as well. He was a filmmaker, he was involved in music, he was an author, he produced television shows, and he dabbled in the world of fashion,” Diaz continues. “Warhol encompassed the culture of his period just as da Vinci did.

“I think da Vinci would be flattered.”

Speaking of flattery, a 1963 Warhol Mona Lisa is a part of the Met’s permanent collection, thanks to Warhol’s friend, Henry Geldzahler, who worked at the New York museum when Mona made her historic visit and would later become its founding curator of contemporary art. Geldzahler may have given Warhol the idea to create his own Mona. Warhol gave Geldzahler one of the paintings as a gift and Geldzahler, in turn, gifted the painting to the Met. (A work in The Warhol’s collection titled Mona Lisa’s Hands originated from the same piece of canvas as the painting gifted to the Met; Warhol cut off two sets of Mona Lisa’s hands as a way to avoid an awkward juncture in the screen print.)

“The fact that the most important painter of the 20th century, Andy Warhol, responds to one of the world’s most famous paintings and it ends up at the Met,” Diaz says, “is quite incredible.”

Receive more stories in your email

Sign up