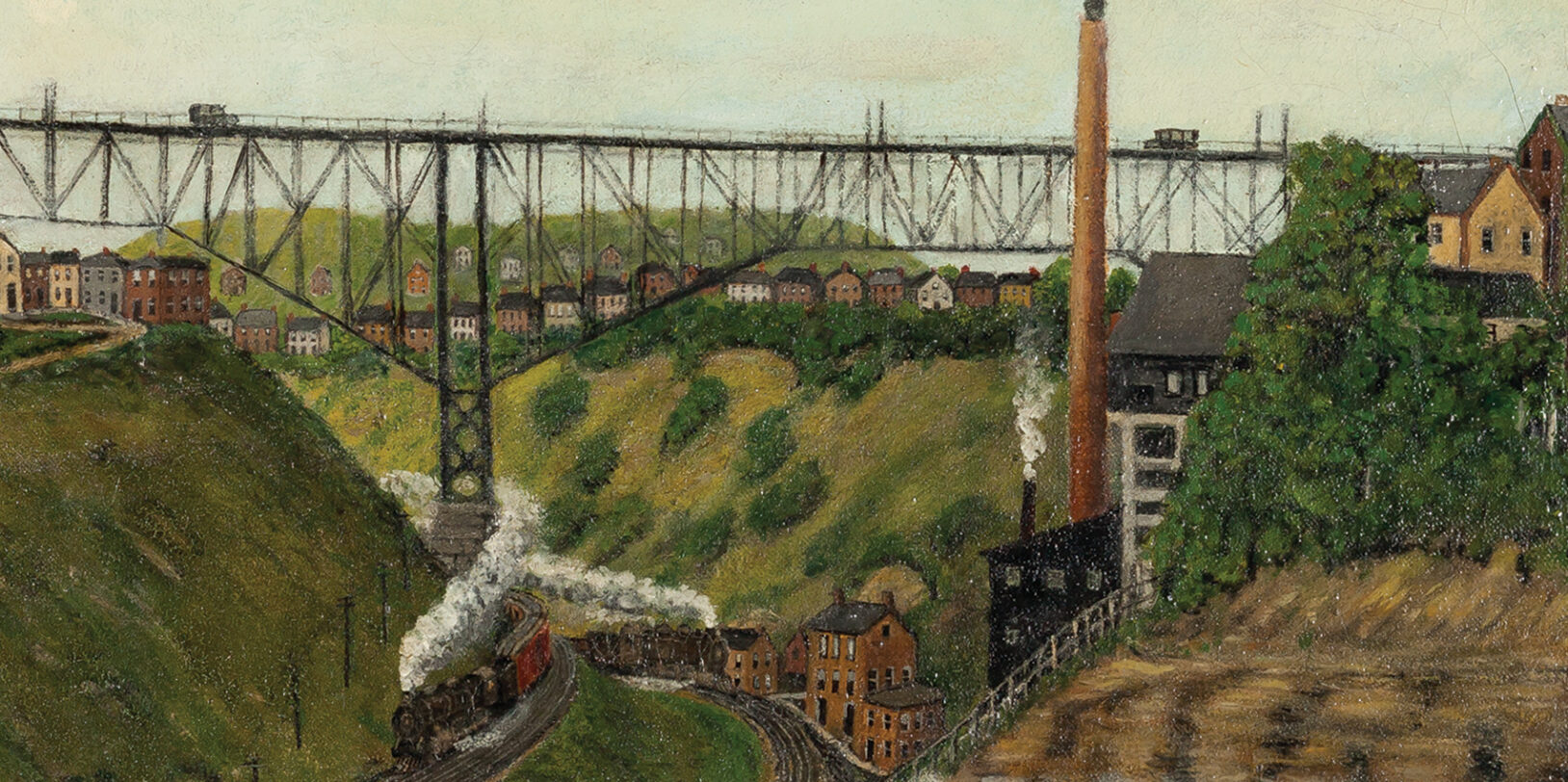

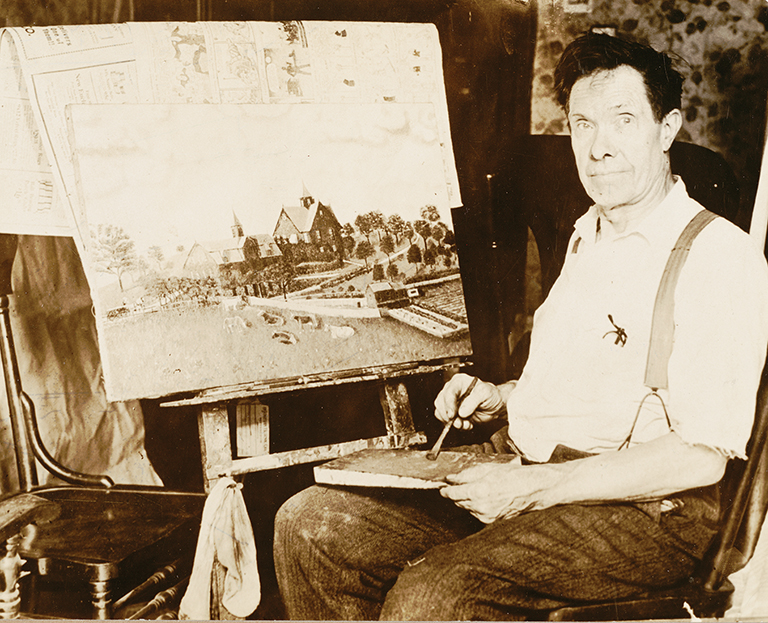

The tattered sign in the vestibule of the rooming house read JOHN KANE, HOUSE PAINTER. From the outside, the man living in a dingy one-room flat in the Strip District seemed like a common laborer. But what he was creating inside the dirty, noisy space overlooking the Pennsylvania Railroad was anything but ordinary. As the trains clattered by, Kane painted striking landscapes of Pittsburgh, its bridges, valleys, and hills.

At age 67, Kane had calloused hands, a weather-beaten face, and a body worn down by decades toiling in steel mills and coal mines, building bridges, and painting houses. He was also being hailed as a great artist.

Kane was plucked from obscurity when journalists interviewed him after one of his paintings was accepted into Carnegie Museum of Art’s 1927 International Exhibition of Paintings, known today as the Carnegie International, the second oldest recurring global survey of contemporary art in the world. The museum selected his composition Scene from the Scottish Highlands, depicting a pair of kilt-clad Scottish dancers and a bagpipe player, from more than 400 entries submitted by most of the major painters of the day.

John Kane, Scene from the Scottish Highlands, c. 1927, Carnegie Museum of Art, Gift of G. David Thompson

“A genius has been discovered!” proclaimed a front-page headline in the Pittsburgh Press. But most reporters were less charitable.

“He was adored by the art world, but he was excoriated by the press,” says Jane Kallir, co-director of the Galerie St. Etienne in New York and author of John Kane, Modern America’s First Folk Painter. “He was a sensation but not in a good way. He was a dancing dog, a curiosity at best, a fraud at worst.” While the well-educated, classically trained artists studied in France and mingled with wealthy collectors, Kane learned to paint on houses and sketched landscapes on the sides of railroad cars.

Breaking into the International in 1927-his second attempt after being rejected the previous year-wasn’t a fluke. Kane’s artwork appeared in the prestigious show six more times, and was quickly added to the collections of not only Carnegie Museum of Art but also New York’s Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, and The Art Institute of Chicago. His work could also be found on the walls of the wealthiest art patrons of the day, including Mrs. John D. Rockefeller, Jr.

Today, Carnegie Museum of Art houses the largest collection of Kane’s work-17 paintings and four drawings-underscoring the importance of the Carnegie International in building the museum’s permanent collection. As the museum plans for the exhibition’s 57th edition this October, it’s remarkable to note that many of the museum’s most iconic works were exhibited in this series.

“Although he didn’t go to professional art school and study Picasso, Kane was nevertheless achieving a bold, striking, interesting, and original composition. And that’s why the work has lasted.”

– Louise Lippincott, curator of fine arts at Carnegie Museum of Art

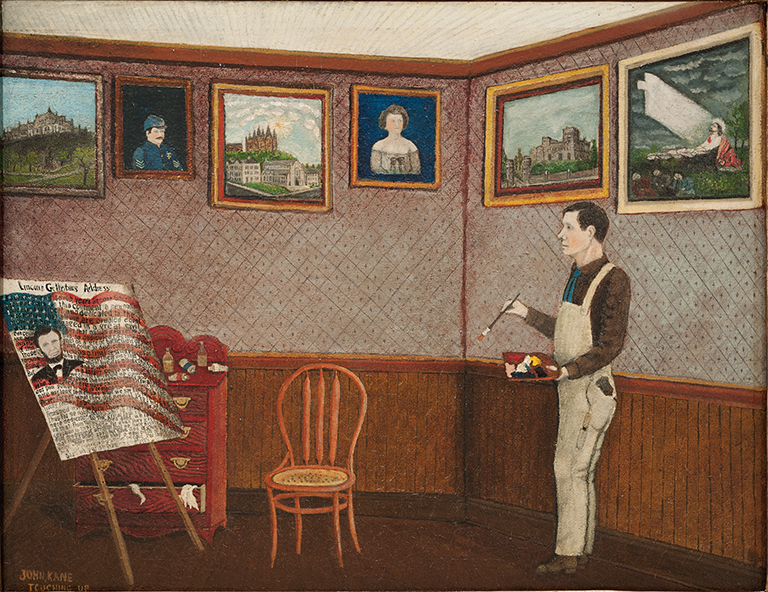

One of the museum’s works by Kane, a two-sided painting, is currently on loan to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., for inclusion in Outliers and American Vanguard Art, a major traveling exhibition celebrating American self-taught and avant-garde artists. It’s organized by Lynne Cooke, senior curator at the National Gallery who Pittsburghers may recall was co-curator of the 1991 Carnegie International. On one side of the panel is a bucolic scene on a western Pennsylvania farm; on the other is the words of the Gettysburg Address and a portrait of Abraham Lincoln surrounded by the text of his speech painted over a rippling American flag.

“This is a good example of how art that is unsophisticated can be unexpectedly modern,” says Louise Lippincott, curator of fine arts at Carnegie Museum of Art. “Although he didn’t go to professional art school and study Picasso, Kane was nevertheless achieving a bold, striking, interesting, and original composition. And that’s why the work has lasted.”

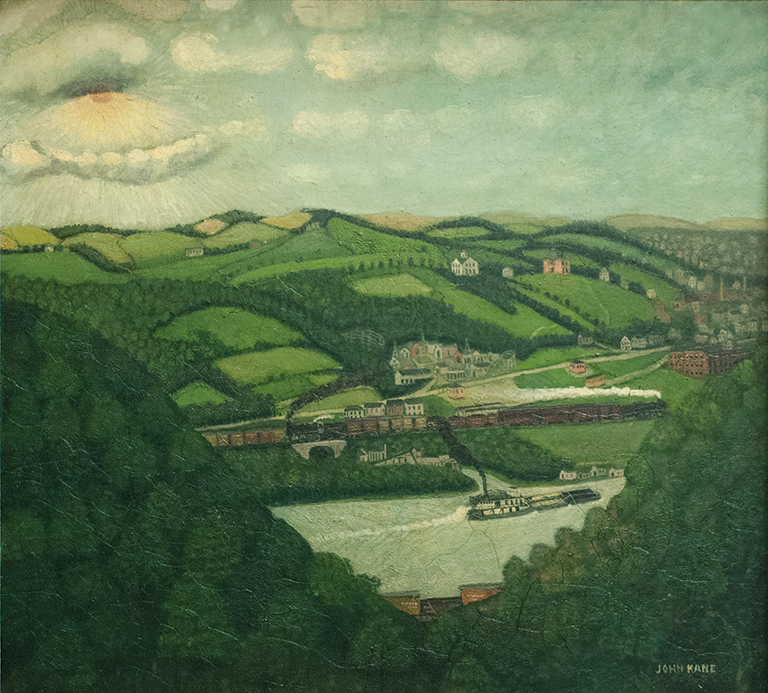

Outliers and American Vanguard Art, which includes work by other artists who created art on the periphery, including self-taught painters Horace Pippin and Joseph Yoakum, showcases two other Kane paintings from the Museum of Modern Art’s collection: his famous self-portrait, and Through Coleman Hollow up the Allegheny Valley, a landscape of the river and valleys in and around Pittsburgh.

“It’s great to see John Kane’s work holding pride of place in our nation’s capital in an exhibition that changes the way we think about American art history and the politics of class, as well as race and gender-because Outliers and American Vanguard Art is that wide-reaching,” says Ingrid Schaffner, curator of the 2018 Carnegie International. “Plus, I like to think that curator Lynne Cooke’s initial regard for Kane might be another of the great achievements of the Carnegie International she co-curated with Mark Francis in 1991.”

John Kane, Pietà, 1933, Carnegie Museum of Art, Bequest of Paul J. Winschel in memory of Jean Mertz Winschel

And, of course, several of Kane’s works, including Scene from the Scottish Highlands and The Cathedral of Learning, can most often be found in Carnegie Museum of Art’s Scaife Galleries. Pietà was based on the famous Avignon Pietà (c. 1455, Louvre, Paris), a photograph of which once hung at the museum. Kane modified the composition to include his self-portrait as the kneeling donor to the left. The roof of Carnegie Museums in Oakland, the nearby towers of St. Paul Cathedral, and an adaptation of the University of Pittsburgh’s Cathedral of Learning (under construction in the 1930s) can be spotted in the background.

Kallir sees a bittersweet quality underlying the work. “He had an extraordinarily difficult life,” she says. “He worked in Pittsburgh at a time when that was no picnic. His family left him. You look at all these paintings of Pittsburgh scenes. They depicted what he wanted to believe was there. Yet under the surface is this alluring sadness.”

The making of an artist

On August 19, 1860, Kane (then spelled Cain) was born in West Calder, Scotland. It’s as though life was conspiring against him being an artist from the start. At the age of 5, he started school and began to draw on his slate. His early drawings won him no awards-only a prompt scolding from the schoolmaster, according to Kane’s as-told-to autobiography, Sky Hooks, so named for the curved steel grapnels hung on roofs to support house painters, one of the many jobs Kane held throughout his life.

At the tender age of 9, he went to work in the shale mines. At 19, he moved with his family to America. As part of the labor force that built industrial America, he took on the most grueling jobs-laying tracks of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, digging the foundation for U.S. Steel’s Edgar Thomson Works, paving streets in Pittsburgh and McKeesport. He helped build the Greenfield Bridge, working high above the city and taking in images that would later make it onto his canvases and eventually into museum galleries.

A brawny young man, he was also an acclaimed amateur boxer. But at age 31, Kane was crossing the railroad tracks at dusk when he was hit by a train running with no lights. His left leg was severed five inches below the knee.

After building his own wooden leg, Kane started a new job as a crossing watchman at the railroad where he’d been hit. From there, he moved on to painting steel freight cars in McKees Rocks, where he began experimenting with color. His earliest masterpieces were landscapes painted on the sides of train cars, each one disappearing under a solid-color coat of paint by the end of his shift.

Unknown photographer, Portrait of John Kane at His Easel, Carnegie Museum of Art, Gift of the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh

Kane married Maggie Halloran, an Irish girl, in 1897, and became the father of two daughters. He supported his family by going door to door in mining settlements, painting portraits for the housewives by enlarging photos and painting over them.

Kane was thrilled to welcome a third child, a boy named John. But two days later the baby died, and Kane sunk into deep grief. Unable to recover, he drank heavily, and eventually his wife left him, taking their two daughters with her. He worked odd jobs but became so destitute that he stayed in a flop house operated by the Salvation Army.

“You look at all these paintings of Pittsburgh scenes. They depicted what he wanted to believe was there. Yet under the surface is this alluring sadness.” - Jane Kallir, co-director of the Galerie St. Etienne in New York

“His life was hardship after hardship after hardship,” says Pat McArdle, a music promoter, former ironworker, and Kane aficionado. Yet for all the hard knocks, Kane saw the beauty under the industrial grit of Pittsburgh. As he drives around the city, McArdle says he recognizes the vivid images of the Kane paintings hanging inside Carnegie Museum of Art: Larimer Avenue Bridge, Bloomfield Bridge, Nine Mile Run, and Panther Hollow-everything rendered in painstaking detail and intricate patterns.

When asked why he painted Pittsburgh, Kane replied, “I helped to build its steel mills and homes; I paved its streets, made its steel, and painted its houses. It is my city; why shouldn’t I paint it?”

John Kane, Sunset, Coleman Hollow, c. 1930, Carnegie Museum of Art, Gift of Sara M. Winokur and James L. Winokur

But he wasn’t creating the dramatic nightscapes of fire-spewing steel mills favored by other artists who flocked to the city. “He’s not showing the ‘hell-with-the-lid-off’ Pittsburgh like so many artists. He shows lovely scenes and rural pastimes,” Lippincott notes. “Other artists said Kane was stuck in the past and looking at the wrong stuff. They laughed at him.”

Kane found a champion in one of those classically trained artists. While studying cubism in Paris, Andrew Dasburg had experienced the sensation created by another self-taught primitive painter, Henri Rousseau. Dasburg recognized the parallels between modernism and the primitive images that Kane created-the use of bold patterns, spatial limitations, and decorative colors.

A judge on the jury for the 1927 Carnegie International, Dasburg convinced others to admit Kane to the show. Suddenly, this poor laborer was being hailed as the American Rousseau, and other museums began to show his work. Dasburg would buy the painting that started it all for $50.

Portrait of a Pittsburgher

Kane also found a sympathetic chronicler in Marie McSwigan, the Pittsburgh Press reporter who spent hours talking to him to compile Sky Hooks. But there was backlash, too, from other reporters and within the art world. One artist even set out to expose Kane as a fake.

Kane’s paintings could be found in the most prestigious museums in the country when the Junior League of Pittsburgh held a show of his work. Kane provided original pieces, but when the organizers told him they needed to fill empty wall space, he sent some of his early work-the portraits he’d made for miners’ wives by painting over enlarged photographs.

John Kane, Touching Up, c. 1931–1932, Carnegie Museum of Art, Gift of Thomas Mellon Evans

Milan Petrovits, a fellow Pittsburgh-based artist, went to a Pittsburgh reporter and told him to remove the varnish from one of the paintings to uncover the photograph underneath. The reporter followed Petrovits’ suggestion and ran damning stories that this so-called genius didn’t create his own work.

The art establishment came to Kane’s defense. Lippincott says the artist’s use of photographic images was common. “There were an awful lot of artists at the time who were using photography,” says Lippincott. “Some of them hid it, and some of them made a point of it. It’s simply another way of working with your subject.”

“I helped to build its steel mills and homes; I paved its streets, made its steel, and painted its houses. It is my city; why shouldn’t I paint it?”

-John Kane

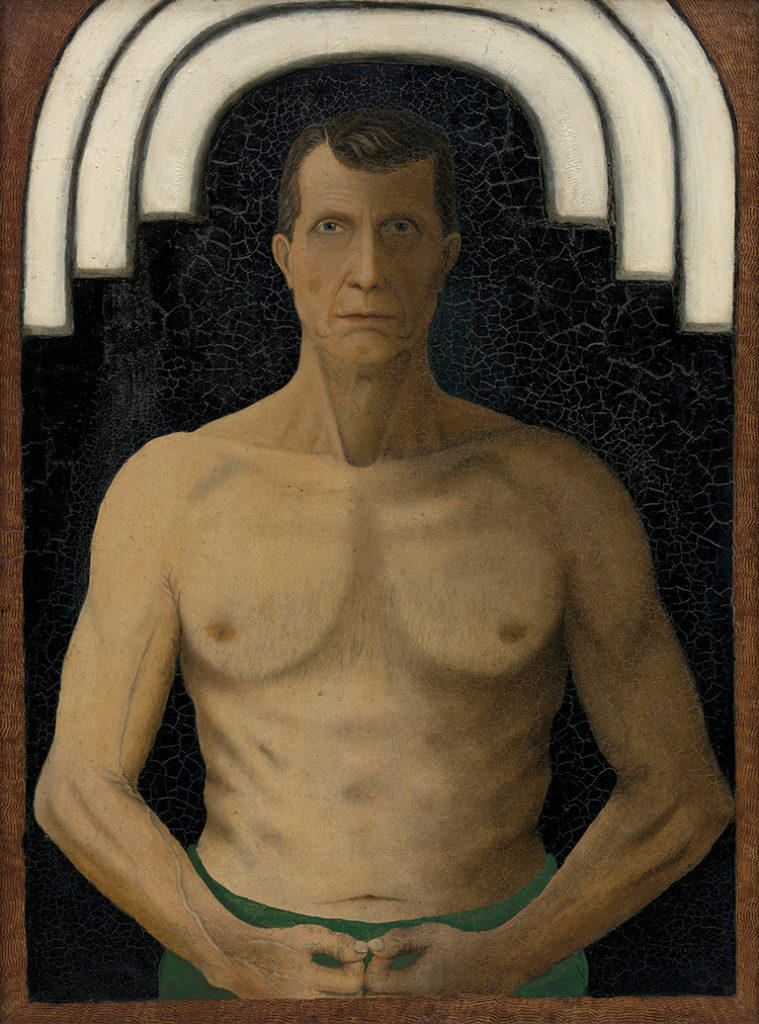

In 1929, at the age of 69, Kane painted his famed self-portrait-an unflinching image of a strapping, bare-chested man staring straight ahead. “It is extraordinarily stalwart,” says National Gallery curator Lynne Cooke. “There is nothing like it in American art. Most artists make themselves grander or more romantic with the cliché of a beret and palette and paintbrush.”

John Kane, Self-Portrait, 1929, The Museum of Modern Art, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Fund. Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, NY

Robert Qualters, the well-known Clairton-born artist who often uses Pittsburgh as his muse for his vibrant images, agrees. “It is one of the great 20th-century self-portraits. There is an immediacy and absolute honesty. There is an old man. It is absolutely straightforward and beautifully designed.”

Qualters says Kane inspired him to concentrate his practice on painting scenes from the Pittsburgh region, both past and present. “He found beauty everywhere in the area around us. His example was always in my mind, a way to give me privilege,” says Qualters. Last year, Carlow University hosted an exhibition featuring works by both Kane and Qualters, two iconic Pittsburgh artists.

Kane died of tuberculosis on August 10, 1934. Buried at Calvary Catholic Cemetery in Hazelwood, he had been hailed as brilliant yet remained in poverty, says Kallir. People abused his naiveté and underpaid him for his work. “There was no one to protect him and provide him with professional guidance,” Kallir says. “One collector would get him drunk and practically steal his stuff.”

In the spring of last year, McArdle and Qualters tried to revive Kane as a household name in Pittsburgh by lobbying to rename the newly rebuilt Greenfield Bridge (originally the Beechwood Boulevard Bridge) as the John Kane Bridge. Kane’s advocates asked Pittsburgh’s Naming Commission to honor a man “whose legacy is the embodiment of positive things about Pittsburgh and the potential in all of us,” said Pittsburgh photographer Jake Reinhart. The effort fell short.

Had it not been for one judge at the 1927 Carnegie International, Kane would have died unknown. As Lippincott puts it, “You would be buying his work at flea markets around Pittsburgh.”

Almost a century later, his indelible art lives on-in some of the greatest museums in the world.